Fort Archives

The National Archives Goes to War

Summer 2003, Vol. 35, No. 2

By Anne Bruner Eales

On Monday morning, December 15, 1941, the staff of the National Archives was crammed into the theater of the building, with some of them standing in the hall, straining to hear. They had come to listen to a pep talk by Solon J. Buck, Archivist of the United States, about the role their agency would play in the war that had begun the previous week.

The staff was well aware that most of official Washington viewed the comparatively new National Archives as a "warehouse for dusty and yellowed old parchments," primarily useful as a dumping ground for records that agencies were no longer interested in keeping.

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Robert D. Hubbard, director of personnel at the Archives, acknowledged in a memo to Buck, "The National Archives is looked upon generally by the public and by officials and employees of other government agencies as an organization of 'parasites' of no value in the present war efforts."

However, many in Buck's audience knew that the National Archives could prove a valuable asset in the coming conflict.

Collas Harris, executive officer at the Archives, soon wrote,

When total war threatens the destruction of . . . civilization, the archivist and the librarian alike are called to help defend it. They must see that the recorded experience embodied in their books and records is brought to the service of the war agencies; they must protect the materials in their care from actual military hazards, which the airplane has carried to cities that in a former day would have been far removed from the scene of war; they must preserve the integrity of their holdings against the damaging effects of emergency activity; and to the best of their ability they must continue and increase their services to those processes of the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge that are the lifeblood of the civilization we are defending.

Since the fall of France in the summer of 1940, the National Archives had been preparing to do all of these things.

As early as 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a member of the Society of American Archivists (SAA) and a strong supporter of the National Archives, had been worried about the protection of government records in time of war. Waldo Gifford Leland, president of the SAA, reflected his concern in a speech to that organization on November 12, 1940. Leland stated, "at present we are in a state of limited emergency. . . . We are apprehensive lest the limited emergency . . . should—perhaps very soon—deepen and spread into the greatest of all emergencies—total war. . . . Fervently we hope that this may not come to pass, but . . . we should now, while there is still time, take the necessary precautions and prepare the indispensable plans."

President Roosevelt, who read Leland's speech, strongly agreed.

In March 1941 his administration created a Committee on Conservation of Cultural Resources (CCCR) under the National Resources Planning Board and charged it with formulating plans for "the protection of the nation's cultural heritage as preserved in museums, libraries, and archives . . . against the possible hazards of war and emergencies, however remote."

Committee offices were established in the National Archives Building, and Collas Harris was appointed as executive secretary. During most of 1941, the CCCR and the National Archives had a symbiotic relationship in archival planning and preparing for World War II—the Archives provided the money, staff, and space, and the CCCR provided the work.

On April 2, 1941, a confidential report authored by Harris acknowledged that the hazards of war were not quite as "remote" as the CCCR charter indicated. "Plainly speaking, this Committee's very existence thus includes the working assumption that, conceivably, the course of foreign and military affairs might force us to examine safety problems which we have never before faced. . . . The threat of bombing from the air comes immediately to mind. . . . Paper planning, well in advance, and its implementation, while not able to avert the unpleasantness of direct hits or the chaos of defeat, had some value in Europe." The CCCR and National Archives were increasingly beneficiaries of lessons learned painfully by their European colleagues. For example, a British report on the wartime function of the Public Record Office showed that as early as 1934 it had considered the possible need to evacuate records and other cultural treasures in case of bombing. By December 1941, more than 1,000 tons had been transported out of London to remote country houses. Some had even been evacuated across the Atlantic—the copy of the Magna Carta exhibited at the 1939–1940 New York World's Fair remained in the United States, and pieces of European art shown at Chicago's Century of Progress Exposition were left "for the duration."

In February 1941, ten months before Pearl Harbor, American archivists began to consider how much space might be needed for the safe storage of valuable U.S. records. They knew that a survey taken in 1935 by R.D.W. Connor, first Archivist of the United States, had found scattered throughout Washington almost 3 million cubic feet of federal records; more than 3,000 miles of motion picture film; 2.6 million still picture negatives; and 5,500 sound recordings. The government needed to know how many of these records, along with artifacts and works of art, ought to be relocated. On September 4, 1941, the CCCR and members of the National Archives staff conducted a detailed survey, sending questionnaires to sixty-eight government departments, agencies, and offices. Returns received by September 29 showed more than 550,000 cubic feet recommended for evacuation, approximately enough to cover a football field to the depth of twelve feet. Results were sent to the Commissioner of Public Buildings on October 15, with a recommendation for construction of large local bomb shelters. Unfortunately funds, manpower, and material were not available for the project. The CCCR then began to formulate plans for possible evacuation of America's cultural treasures from Washington, New York, and other cities within a hundred miles of either coast.

In May 1941 the National Archives had performed a test evacuation of records in its custody. It had determined that it would take almost 60 days and more than 2,000 truckloads to remove more than 80,000 containers of material from the National Archives Building. However, anticipating that evacuation would eventually be necessary, in September 1941 the National Archives put in an order for $35,000 worth of packing boxes. Proposed depositories for these evacuated records included the Illinois State Library at Springfield, the North Carolina Historical Commission in Raleigh, and old post offices at Johnstown, Pennsylvania, Portsmouth, Ohio, and Clarksburg, West Virginia.

Undoubtedly based at least in part on the May test and certainly prepared before Pearl Harbor, in December 1941 the National Archives issued its Bulletin Number 3, The Care of Records in a National Emergency. The publication stated that during times of war, records had to be guarded against several kinds of danger:

- transfer of personnel trained to take care of them,

- diversion of funds to types of work considered more urgent,

- space requirements for uses other than the storage of records,

- the threat to records due to the greatly increased value of waste paper, and

- the less immediate but more easily defined danger of possible enemy action.

If it became necessary to evacuate material, the bulletin said the first rule was to prevent the files from being disarranged. If possible, they should be transferred in their original containers. However, whatever boxing method was used, the finished product should weigh around a hundred pounds—small enough to be handled by one man—and be tagged or marked to indicate the custodial institution and the contents.

The archival community had recognized very early that one of the most difficult things to decide about evacuation was exactly what should be moved. Bulletin No. 3 indicated that the basis for determining the most valuable material could be uniqueness, age, irreplaceability, and legal or research value. The National Archives reported that it had analyzed the records in its custody and placed them in three groups. Group I included those records whose loss would result in damage to "public morale and the Nation's honor"; Group II covered essential records, the loss of which would prove a serious handicap to government agencies, scholars, and others; and Group III, the great bulk of material, which contained records that were important but not "fundamental" or "essential." The last were not to be relocated.

In fact, comparatively little of the 550,000 cubic feet of material was ever evacuated. When the CCCR received the survey total in September 1941, Collas Harris had decided that the small amount listed for removal probably indicated a general reluctance by agencies to surrender control of their most valuable items.

Nevertheless, such events as the fall of France, the bombing of Britain, and the anxiety generated by the press and newsreels at their local theaters made the possibility of war more of a certainty for most Americans. Government officials felt a growing concern about the safety of their records. The CCCR made inquiries to the War Department concerning "the nature, extent, degree, and imminence of military hazards" to cultural resources, and received the response, "Bombing attacks on coastal cities . . . are best described as likely rather than improbable or remote."

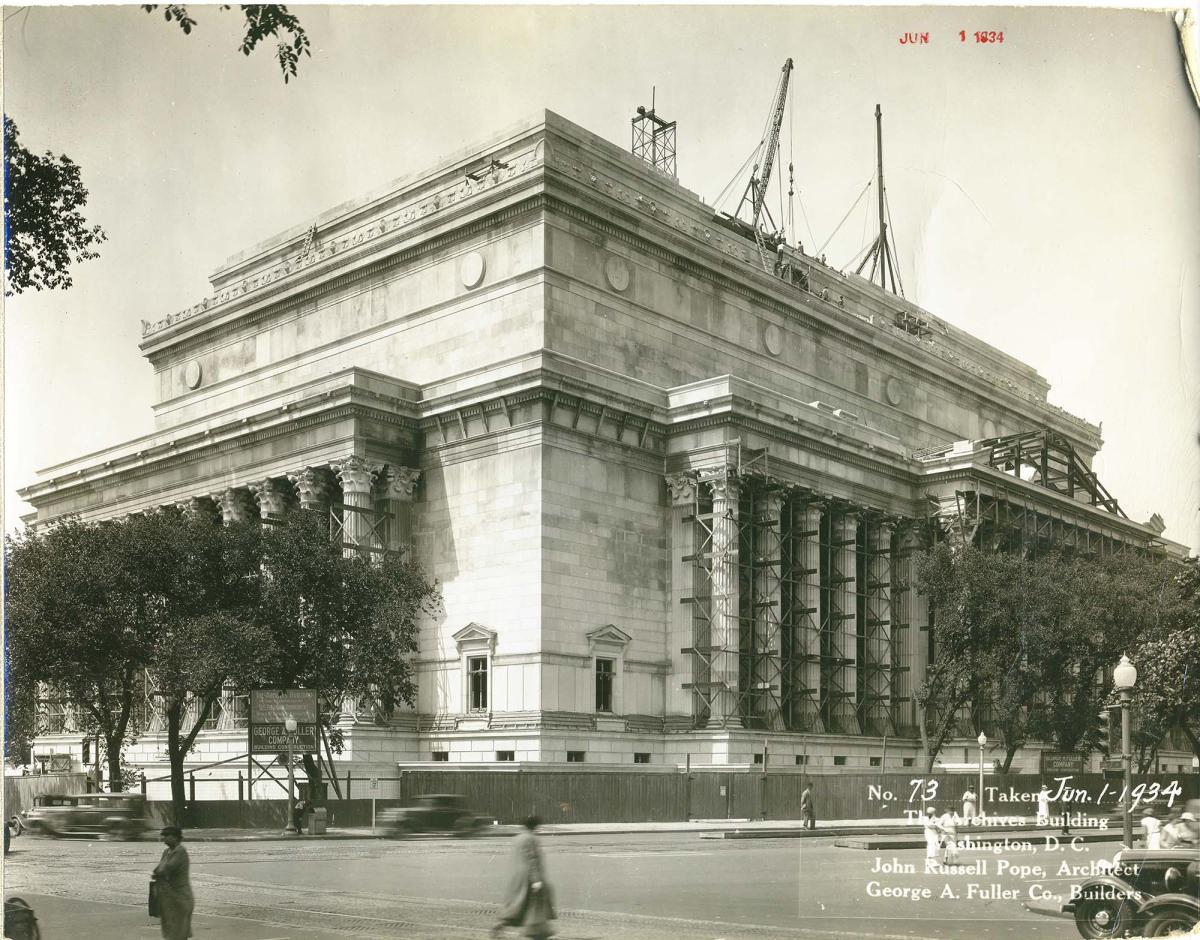

It was in this environment of elevated concern that administrators read in an April 20, 1941, article in the Washington Post, "The Library of Congress . . . is easy prey to aerial bombs. The same could be said of most of the public buildings in Washington with one notable exception—the National Archives." A later article reported, "Long before Pearl Harbor—and even before Munich—Uncle Sam built himself a bombproof shelter. The shelter is meant for papers, not for people. . . . Officially named the National Archives and with important peacetime uses, the bombproof [sic] today houses America's most perishable assets. . . . the inner building of the National Archives, a tall, tough cube set into a space intended for an open courtyard . . . a building within a building, with six layers of reinforced concrete and 10 steel decks for overhead protection." The press began calling the building "Fort Archives."

Government officials gradually came to realize that the National Archives Building could be far more than a repository for castoff records. During the quarter ending March 31, 1941, they had transferred to it only about 8,000 cubic feet of material. When America entered World War II eight months later, quarterly accessions into the "bombproof" had increased by more than 600 percent. The 175,000 cubic feet accessioned in 1942 mitigated another important government concern by releasing 40,000 square feet of vitally needed office space in other federal buildings.

Even more room was gained when Archives appraisers authorized for disposal about a million cubic feet of records, freeing enough space to provide offices for fourteen thousand people. However, as the Baltimore Sun had once observed, "pity the archivist" who chose unwisely on what to keep and what to destroy. He (there were few women archivists at the time) could play it safe and save everything, "but in that case he will need not one archives building but a hundred or so of them."

Even if only truly valuable records were transferred, it became increasingly apparent that the National Archives Building could not hold all the government material likely to be created during World War II. Over 80 percent of War Department records gathered from 1789 to 1918 had originated during the nineteen months of America's involvement in World War I—ream upon ream, file drawer upon file drawer, linear mile upon linear mile of records. A similar experience in the upcoming conflict would produce, as Collas Harris wrote, a "nightmare of hopeless burial beneath an unceasing, overwhelming flood of paper." President Roosevelt proposed a solution to the situation on August 26, 1941, when he called for construction of a new War Department building in Arlington, Virginia. The President said that he intended the new building, which eventually would be called the Pentagon in recognition of its shape, to be used only temporarily by the War Department. After World War II was over, the more than two-million-square-foot facility would become a storehouse for tons of valuable government records. Representative John J. Cochran of Missouri strongly agreed with Roosevelt about the need for a new records repository. The Archives, he stated in an August 27, 1941, article in the Washington Star, had become nothing more than a showhouse filled with junk.

The Archivist of the United States was determined to show that it was considerably more by having the National Archives designated as a National Defense Agency. This would identify it as a significant contributor to the war effort and award it a commensurate priority for funding and personnel. In his October 17, 1941, application to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, Buck linked the agency's mission to the war through its responsibility for the important work of storing, disposing of, and responding to requests for information about all records of the federal government. He indicated that the last was an especially important task, given the increasing number of inquiries from new government offices about actions taken by related agencies in World War I. Buck explained that the Federal Register division of the Archives printed such things as summaries of defense contracts, Presidential proclamations, and executive orders, rules, and regulations that were used daily by almost every element of government. Whether due to the President's personal interest in the Archives or Buck's salesmanship, when the list of defense agencies was published in February 1942, the National Archives was included . . . barely. It was sixth from the bottom in Class 5, the lowest category. Others in the same class were St. Elizabeths Hospital, a historic mental institution in the District of Columbia; Washington National Airport; and the groundskeepers at the White House—all of them higher than the Archives in personnel and funding priority.

By September 1942 Buck could provide tangible evidence of the agency's value in the war effort and asked that the National Archives classification be increased to category 3. He stated that from the attack on Pearl Harbor to the end of the fiscal year (June 30, 1942), the Archives had provided the Navy Department with the records of some 56,000 former enlisted men who wanted to return to the service. This had given the Navy enough experienced sailors to operate thirty-six battleships or aircraft carriers. The cartographic section had aided the air war by providing several hundred detailed maps of foreign cities, including Bremen, Cologne, Hamburg, Berlin, Kobe, and Tokyo. Supporting letters from various officials, including the secretary of war, were enclosed with Buck's request, and on September 25, 1942, the Archives was increased to Class 4.

Despite its designations as a war agency, keeping qualified employees was a problem for the National Archives throughout World War II. Staffing levels at the agency were "professionals," such as archivists and librarians; "semiprofessionals," such as archives and library assistants, nurses, and laboratory aides; a large clerical-administrative-fiscal section (category CAF) that included specialties such as editors, purchasing officers, photographers, telephone operators, personnel and file clerks, and secretaries; and skilled and unskilled laborers (category CU), such as cabinet makers, printers, mechanics, messengers, and chauffeurs. During the war the staff turnover in some of these areas reached almost 150 percent. Hiring replacements was difficult, especially in the professional and semiprofessional categories because of the educational requirements—in 1939, of 319 employees, 160 held bachelor's degrees, 73 had their master's, and 32 had been awarded their doctorates. The armed forces had great demand for college graduates, a comparatively small percentage of the population in 1941. More than 25 percent of the National Archives staff either joined or were drafted by the military, the highest percentage for any government agency.

These "military separations" and the transfer of over 250 people in a single year led to new employment opportunities for women and blacks. At the beginning of the war, only seven women were among the seventy-nine archivists; two years later there were thirty-three, an almost 500-percent increase. To meet a growing gap in scientific and technical workers, it was announced in the Washington Star on November 26, 1942, that the National Archives and other government offices were preparing for the first time to employ "female trainees" in these areas.

While the National Archives record of employing blacks was better than some other agencies—10 percent of the staff in September 1941—most were in unskilled jobs. Establishment of the Committee on Fair Employment Practices in 1941 encouraged government agencies to offer new opportunities to blacks, and by August 31, 1942, 15 percent of the National Archives staff was "colored"—one professional, five semiprofessional, three CAF, and fifty-nine CU. The November 1943 "Report on Negro Employment" showed that the Archives had two black professionals and eleven semiprofessionals; by the end of the war there were three and fourteen.

In the days after Pearl Harbor, the responsibilities of Archives employees, whatever their sex or color, expanded to include security of the National Archives Building. On December 3, 1941, just four days before the attack in Hawaii, Collas Harris recommended establishment of an Archives committee on protection against the hazards of war (PAHW); on December 8, the Archivist agreed and appointed Harris as chairman. The PAHW was to be responsible for making and carrying out recommendations to the Archivist regarding protection of the National Archives Building and its contents—including personnel, which seemed to come almost an afterthought in the committee charter. The first meeting took place from 10:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. on December 8, and, struggling to establish wartime staff organizations and functions for the agency, it met nine more times in December. Some meetings went until 1:30 a.m. Problems discussed included such issues as military protection for the National Archives Building; transferring or evacuating the more important records; and the establishment of employee squads to perform various defense functions within the building.

On December 23, 1941, all staff members, except telephone operators, received a volunteer packet with an enclosed form that was to be filled out and returned immediately to the director of personnel. The form gave them a choice about whether they wanted to volunteer their services with the watcher (later air-raid warden), first aid, fire-fighting, evacuation, demolition, decontamination, or canteen squads. Telephone operators were excluded from participation because coordination of civil defense efforts in the building would be carried out over the telephone switchboard.

The most important and demanding task for volunteers was service with the twenty-four-hour-a-day watcher/air-raid warden squad. Since the military had informed government agencies that coastal cities were vulnerable, one of the first concerns for the PAHW was establishment of a group to guard against surprise attacks on the National Archives Building. It suggested that this squad "patrol the 21st Tier Roof of the building . . . and . . . patrol the outside . . . for the purpose of preventing possible sabotage and for signaling in the event of air raids." From December 8, 1941, to January 1, 1942, 121 men devoted 2,705 hours to air-raid warden activities.

Philip Hamer, chief of reference service, was concerned that this was a large amount of time to spend just waiting for something to happen and suggested that "plans should be worked out whereby they can carry on certain work with records during such time as protective action is not necessary." The committee agreed and requested that the chiefs give definite tasks to any personnel assigned to protective activities between 4:30 p.m. and 9:00 a.m. During the first six months of the war, the Division of Printing and Processing took advantage of this order and used watcher assistance to collate and hand-staple more than a million pages of National Archives publications.

A special function of the squad was to serve as monitors during air-raid drills in the building. Since the spring of 1941, the Archives had known that the "inner cube" extension of the National Archives Building contained the most protected areas against bombing. The safest point for records—or people—would be on the third tier of the extension, and that is where the PAHW established the bomb shelter. A control center to direct the activities of all air-raid protection squads was set up in Room G-13. Shelter signs were posted, sand containers were put in corridors throughout the building in case of fire, and new batteries were provided for all the flashlights. Every single one had failed during the first air-raid drill, creating a true blackout condition in the many windowless spaces.

The committee debated the issue of whether to allow the public access to the Archives air-raid shelter. Given the reputation of "Fort Archives," it was likely to be a popular place with people in the surrounding buildings. The Public Buildings Administration had recommended that in the event of an air raid, entrance doors to government buildings should remain open so that the general public could seek shelter. The PAHW agreed but said National Archives employees were to be given first preference. Then, if not everyone from the street could be accommodated, the overflow would be advised they could remain in the lobbies "if they so desire." During an early drill, 120 members of the public took refuge in the National Archives: 70 were allowed into the shelter, and 50 more "so desired" to remain in the lobby just inside the Pennsylvania Avenue entrance.

The shelter might have been even more crowded if everyone in the building had been able to clearly hear the air-raid alarms. In some areas, particularly the upper tiers, the alarms could not be heard at all. Even when they were audible, instructions concerning the various air-raid warning bells, such as "Washington Blue," "Washington Yellow," and "red alarm," were extremely confusing and probably would have led to chaos in an actual attack. At one point in the war, the "blue" signal, which had previously meant "all clear," was changed to mean that an attack was approaching. The Archives was not even notified when a "Washington Yellow" alarm was sent out. It was received across the street at the Justice Department, and someone either had to telephone or hand carry the alert to the National Archives Building.

The Archives, CCCR, and even the President of the United States were all concerned that one of the greatest dangers from an air raid on the nation's capital would be the more than four hundred tons of highly flammable nitrate film estimated to be in the area. The film gave off a lethal gas when burning and under certain conditions was highly explosive. In response to an inquiry from President Roosevelt, Solon Buck reported on July 20, 1942, that arrangements were under way to relocate the film to some abandoned powder magazines and gun emplacements at Fort Hunt in Fairfax County, Virginia. The fort, though near Washington, was in an almost unpopulated area, and the Archivist assured Roosevelt that the emplacements were of massive rock concrete construction, especially designed for the storage of flammable and explosive material. It was estimated that the space might be able to house over a million feet of motion picture film.

Vernon Tate, chief of the Division of Photo Archives and Research, was not as enthusiastic about the relocation to Fort Hunt. He had inspected the vaults in the summer of 1941 and found only one to be fairly dry. Tate reported that if the magazines were to be used for storage, they should all be cleaned and repaired, with drains placed in operating order, shelves erected to keep the film at least six inches off the floor and four inches from the wall, and ventilation ports screened to keep out rodents and insects.

Although the Public Buildings Administration undertook an extensive rehabilitation project at the facility, Tate later wrote that "storage conditions . . . at Fort Hunt are something less than ideal." Negatives stored there had deteriorated so badly that they were stuck to the negative preservers. Tate wanted to send someone to inspect the film at intervals of six months but found that was extremely difficult to do. The commanding officer of the post would not allow any female personnel to visit or work at the facility, and several members of Tate's staff were women.

Nitrate films were the only government records evacuated by the National Archives during the war. Rather than remove records, the National Archives Building was divided into four areas having varying degrees of protection from bombing attack, and the agency simply transferred its holdings within the building, depending on the priority of safety they required. The safest area, tiers 3 to 6 of the extension, contained space for some 75,000 cubic feet of records. In May 1942 the Indianapolis Star reported that stored there were such things as the photographs and films of the Byrd expeditions to the North and South Poles, the court records of the Abraham Lincoln assassination, the original Emancipation Proclamation, the Brady Collection of Civil War photographs, and the personal report of Andrew Jackson on the Battle of New Orleans. The paper said the Bill of Rights was packed and stored in the vault below the Rotunda, ready for removal from Washington if that should ever be necessary.

In addition to organizing this relocation of records within the building, the PAHW also took precautions to limit access to the National Archives Building. A control clerk was placed at the Seventh Street entrance to restrict entry to the underground parking area and loading dock, and the doors and gates leading from the Exhibition Hall to the main floor lobby were locked. All visitors to the building had to be escorted to and from their destinations. The committee lengthened the hours of the cloakroom, near the Pennsylvania Avenue entrance, where employees as well as visitors were now required to deposit their belongings.

The group had several discussions concerning the use of identification badges. ID cards had been issued to each employee on March 24, 1941; however, the cards were only needed for after-hours access to the building. The PAHW now recommended that the staff wear picture badges but did not include in this requirement any identification cards for the maintenance crew or employees of other government offices detailed to the National Archives. The committee suggested that numbered badges be issued to visitors, with white ones given at the Pennsylvania Avenue entrance to researchers and red at the Seventh Street entrance to those making deliveries. The chief of reference service strongly objected to the use of badges. Philip Hamer wrote directly to Buck, "The wearing of badges is intended by those who propose it to protect records against sabotage. . . . Even if it be granted that there is real danger of sabotage, the use of badges will not protect us against it. Badges can be stolen or easily duplicated. And I cannot forget the story of one clerk in a war agency who wore Hitler's picture on his badge for two weeks without detection." The controversy over the badges was heated, and the Archivist wavered on this decision. In 1943 the only badges in use were still those issued in 1941.

Although the likelihood of air attack articulated by the War Department in early 1941 remained the official characterization of the threat in late 1942, concern over air raids and sabotage lessened, and security requirements were gradually relaxed. On October 6, 1942, the twenty-four-hour patrol by the wardens was cancelled. February 23, 1943, packages and belongings brought into the National Archives Building by employees and visitors no longer had to be left at the cloakroom. Areas reserved as bomb shelters were returned to the storage of records on April 16, 1943, and six months later, sand containers were removed from the building "in view of the diminishing likelihood of enemy attack on Washington."

This lessening of security facilitated the Archives' ability to handle the enormous influx of wartime visitors to the National Archives Building. During one quarter, 7,845 people not on the staff arrived through the Pennsylvania Avenue entrance. The Red Cross had a group that met in the building to roll surgical dressings, and servicemen came to hear concerts presented by the Record Music Association. Hundreds attended military meetings in the building; in the spring of 1943 alone, the National Archives hosted three confidential conferences sponsored by the War Department General Staff and the Military Intelligence Division (G-2). High-ranking officers of seventeen countries came regularly to attend screenings of war training films given by the United Nations Central Training Film Library. A social organization, the United Nations Club, was formed, and in December 1942 it sponsored, with the National Archives, a festival of entertainment films in the building. One night it was hosted by Comdr. M. A. Skragin of Russia and another by Maj. Hal Roach of the U.S. Army. Exhibits continued in the Rotunda area, and during one month, 10,000 people—2,500 of them servicemen—visited a display of materials from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

The maintenance of building security with so many visitors was a demanding task for the guards, but sometimes a single person could be more challenging. When a visiting military officer told the guard he had come to do business with the Archivist of the United States, the guard responded, "Archivist? We don't have anything like that around here." The security man, obviously new to the Archives, didn't recognize the title, but also didn't recognize the visitor—Gen. George C. Marshall, U.S. Army Chief of Staff.

The majority of people who visited the National Archives during World War II were government employees doing research in the records. In a 1942 article in the American Archivist, E. G. Campbell told how "newly appointed government officials who swarmed into Washington fresh from private industry to head defense agencies could only turn to the manuscript records of their predecessors of twenty-five years ago. . . . How did it work? What were its procedures?" He reported that papers of the War Industries Board, the Fuel Administration, and other similar agencies contained the history of America's World War I attempt to achieve total industrial mobilization, an effort so successful that even the government of Nazi Germany studied these records. J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI, was also interested in the records of the First World War—he wanted to study the history of German sabotage in the United States. Mary Anderson, director of the Women's Bureau at the U.S. Department of Labor, sent inquiries about World War I housing for women war workers, which she felt would be "very useful in our consideration of a similar problem now." When the War Production Board wanted to place an expert tool-and-die maker in an airplane plant, the man's citizenship was in doubt. He was able to go to work on the production line because records in the National Archives showed when and where his parents landed in this country, and when they were naturalized.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur noted that records were of special value to the military during war. "More than most professions the military is forced to depend upon the intelligent interpretation of the past for signposts charting the future." When the military was looking for information about a certain mountain pass in enemy territory, the Archives provided a detailed map sent home after World War I by a former consular attaché. Meteorological records, in constant demand for the study of weather history in strategic areas, were particularly valuable in planning for the landings in Normandy.

Movie writers and directors, such as Lt. Col. Frank Capra and Comdr. John Ford, sat in on screenings in the National Archives theater looking for material they could use in wartime productions. Newsreels prepared by Paramount, Fox, and Universal Pictures used footage from Archives films to acquaint Americans with military leaders such as Eisenhower, MacArthur, and Patton.

Services provided to the Navy Department by the National Archives were considered so valuable that the navy established a teletype connection between the department and the National Archives Building to expedite the flow of information. On July 18, 1943, the Washington Star reported, "The National Archives may be a depository for supposedly 'dead records,' but because of the war they have come to life and are doing their share to win the conflict." The Archives had more than earned its right to be on the National Defense Agency list.

Although the vast majority of the more than one thousand requests for information that the Archives received every day—one every thirty seconds—were directly related to the war, 20 percent were not. While the current conflict was being fought in Europe and the Pacific, the National Park Service was searching for records dealing with the Civil War battlefields at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania Court House in Virginia. The Library of Congress needed photostats of twenty-seven documents relating to Walt Whitman, and the warden at Alcatraz wanted information concerning damage to the island at the time of the San Francisco earthquake.

Servicing all these requests—eventually more than 230,000 a year—became an ever greater burden as the staff of the National Archives shrank from a high of 502 in 1942 to 337 by the end of the war. About sixty employees were detailed during the war to work on projects for other government agencies, such as the War Department, Bureau of Aeronautics in the Navy Department, and the Office of Civilian Defense (a functional forerunner of the Federal Emergency Management Agency). In a seminal effort at records management, many of these staff members were told to "spread the developing gospel of records administration." They were to encourage agencies "to establish and maintain their files in a more orderly and economical manner so that with the conclusion of the war the records . . . would be compact and well organized."

Some of those working on special projects were technical experts in the fields of microfilm, sound recordings, maps, motion pictures, and photography. The skill and equipment to microfilm records was considered particularly valuable, and the war guaranteed that the National Archives, which had both, would be a leader in the effort. On February 13, 1942, President Roosevelt wrote to the president of the Society of American Archivists that under the conditions of modern war, "none of us can guess the future." He expressed the hope that the society would "do all that is possible to build up an American public opinion in favor of what might be called the only form of insurance that will stand the test of time. I am referring to the duplication of records by modern processes like the microfilm." Bulletin No. 3, issued in December 1941, had already suggested that microphotography could certainly provide insurance copies of records, ease the pressure for space, and often be an excellent alternative to evacuation. A microfilming experiment performed in August 1941 on 160,000 individual assessment records had been particularly impressive. The original six-by-eight-inch assessment cards occupied files five feet high, twenty-five feet long, and two feet deep, while the microfilm of them was about the size of a dictionary. Such results made government offices extremely interested in filming their records, and the Archives provided them with expert advice and even space to do the work. On November 24, 1941, units of the Navy Department moved into the National Archives Building and eventually filmed more than four thousand cubic feet of its most secret and confidential correspondence, reports, tracings, and plans. Then, rather than relocate the originals, the Navy simply evacuated these much smaller insurance copies to a repository in the interior of the nation.

The navy was not the only government office to occupy space in the National Archives Building. In March 1942, the navy, War Department, War Records Administration of the Bureau of the Budget, and the CCCR had 57 employees working in the building; by June that number had risen to 101. The largest occupant during the war, at least in terms of space, was the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which gathered and analyzed intelligence information and planned and executed operations under the jurisdiction of the World War II Joint Chiefs of Staff. These activities required information, information meant the use of government records, and that needed the assistance of the National Archives. On December 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor, the Archivist of the United States offered to help the OSS, and the organization initially received quarters in the building on April 22, 1942. The allocation of space steadily increased; by 1944 the OSS occupied almost 15,000 square feet of the National Archives Building. Approximately 7,500 square feet was provided in exchange for a naval commission for Vernon Tate and the condition that he be assigned to the Map Division of the OSS so that he could, as an officer, supervise both the Photo Division and OSS operations in the Archives Photo Laboratory. Eight other Archives staff members, five of them women, provided technical assistance to the organization, microfilmed maps and other secret data, and supervised use of an optical printer and specialized sound and editing equipment.

In January 1944 the OSS Map Division moved into Room 400 (now the Microfilm Reading Room), changed the locks on the doors, and declared it a restricted access area. OSS staff members began entering the facility late at night with large, flat items covered by tarpaulins. This "highly classified material" being perfected at the National Archives was a set of maps of beaches that would soon be known as "Utah" and "Omaha." In April 1944 high-ranking officers from all over the world gathered at the Archives to see an OSS exhibit of "certain secret military equipment and devices" that apparently were going to be used in the Normandy landings.

When the U.S. Army arrived overseas, so did some American archivists. President Roosevelt and Solon Buck were both known to be deeply interested in the plight of the "forgotten men" emerging from concentration camps with, as stated by the New York Times on April 18, 1944, "no tangible or documentary relationship to the civilization to which they once belonged." In an effort to bring order to foreign records that had been bombed and scattered, the President allowed Fred Shipman, director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, to serve in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations and at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) as a temporary archives adviser. Capt. Collas Harris performed the same service for the military government in Japan, and Maj. Arthur Kimberly, formerly chief of the Division of Repair and Preservation at the Archives, went to Manila to help the government of the Philippines reconstruct its records.

Although comparatively few American records were damaged in the war—primarily in Hawaii and the Philippines—Archives staff members anticipating the end of the current conflict wanted to prevent the chaotic condition they had found in World War I material. Collas Harris wrote in February 1942, "There is no question but that after the war there will be vast accumulations of records of the present war and emergency agencies. Because there was no agency or organization authorized and equipped to handle records of disbanded agencies after the last war, many valuable documents became lost, destroyed, or disorganized. . . . This situation should not occur again, for the National Archives was founded primarily to take over and preserve important Government records."

However, the Archives' task was not just to compile records but also to assimilate them in context. In response to a 1943 request from the President, the Bureau of the Budget formed a committee to preserve "for those who come after us an accurate and objective account of our present experience." The group encouraged government offices to "maintain records of how they are discharging their wartime duties," and twenty-nine agencies had historical units by the end of 1943. Eventually forty government offices used records to prepare World War II history projects.

The National Archives was one of them. On June 4, 1946, President Harry S. Truman wrote to the Archivist of the United States, "The experience of the Federal Government in the war just ended is full of meaning in relation not only to possible future emergencies but also to the problems of peace. The things we did and endeavored to do and the lessons we learned need to be studied thoroughly and dispassionately both by agencies of the Government and by the independent resources of scholarship. . . . I would like to see prepared and published such guides to the records of our wartime experience as will make the pertinent materials known and usable." The Archives responded to the President's request with the two-volume Federal Records of World War II. This publication also fulfilled the Archives inscription—What Is Past Is Prologue—and was arguably one of the agency's greatest contributions in the Second World War.

Archives involvement in World War II had preceded its beginning and now continued beyond its end. Staff members collected a history of radio broadcasts covering December 7, 1941, the first day of America's involvement in the war, and D-day, June 6, 1944. Exhibits were prepared that displayed to the American public the German and Japanese surrender documents; Hitler's marriage certificate, private will, and last political testament; the original Yalta agreement signed by Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill; and the agreement of the Combined Chiefs of Staff to launch the Normandy Invasion. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright opened the exhibit of the Japanese surrender documents because, as the Archives announced, "the defense of Corregidor by General Wainwright and his associates symbolizes the spirit and indomitable will of the American people that made victory possible." Maj. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, the hero of Bastogne, unveiled the German surrender documents to a crowd that included cabinet members, senators, representatives, Supreme Court justices, the combined chiefs of staff, and members of the diplomatic corps. Hundreds of thousands came to see these exhibits in the building of "dusty and yellowed old parchments." Few of them had understood the value of an archives when the war began, but the devastating conflict had provided the National Archives with a positive opportunity to establish its identity, its importance to the government, and its value to the American people.

As the Baltimore Sun reported, the Archives even got the last word on the war. On September 19, 1945, at the direction of the President, the Federal Register announced that the conflict was now to be known as "World War II." The period of "grief and turmoil, of devastation and heroism" was officially over.

Anne Bruner Eales, a publications specialist at the National Archives, is currently writing the inventory for Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration. A military historian and published author in her own right, Ms. Eales is also preparing a book on America's involvement in the China Relief Expedition of 1900.

Note on Sources

The information for this article was taken primarily from the following series in Record Group 64, Records of the National Archives and Records Administration: Office of the Archivist, Functional Classified Files, 1935–59; Archival Subject Files of Solon J. Buck, 1939–45; and Educational Program Division, Press Clippings, 1937–63. Some references are from Donald R. McCoy, The National Archives: America's Ministry of Documents, 1935–1968 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978). Archives staff members who provided valuable and much appreciated assistance include William Cunliffe, Louis Holland, Judith Koucky, Robert Kvasnicka, Lawrence McDonald, and Richard Peuser.