Question 22: 1940 Census Provides a Glimpse of the Demographics of the New Deal

Summer 2012, Vol. 44, No. 2 | Genealogy Notes

By Ashley Mattingly

As many genealogists, historians, and researchers have discovered, studying census records can lead down many paths and encourage investigation into additional records. The recent release of the 1940 federal population census presents the opportunity to learn more about people, trends, locales, family relations, and the state of the nation.

During the spring of 1940, the nation was still lumbering through the Great Depression following the stock market crash in October of 1929, and agricultural workers were experiencing the strange contradiction of drought conditions and a surplus of goods. As a result, census enumerators posed a new question, the 22nd one, regarding employment of individuals over the age of 14: "Was this person at work for pay or profit in private or non-emergency Government work during week of March 24–30?" If the answer was no, the enumerator posed a follow-up question: "If not, was he at work on, or assigned to, public emergency work (WPA, NYA, CCC, etc.) during week of March 24–30?"1

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created emergency relief agencies, such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), to address the severe economic problems of the early 1930s. When Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933, he declared to a nation suffering from a 25-percent unemployment rate: "Our greatest primary task is to put people to work." The CCC and WPA were formed not only to give work to eligible unemployed individuals but also to mitigate the country's environmental, agricultural, and social problems. Those needing to work were paired with work that needed to be done.

The Civilian Conservation Corps

The CCC was among the first emergency agencies created. Three weeks after his inauguration, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6101, "An act for the relief of unemployment through the performance of useful public work, and for other purposes." On May 7, 1933, in his second fireside chat, he declared:

[W]e are giving opportunity of employment to one-quarter of a million of the unemployed, especially the young men who have dependents, to go into forestry and flood-prevention work. . . . In creating the Civilian Conservation Corps we . . . are clearly enhancing the value of our natural resources, and we are relieving an appreciable amount of distress.2

As a result, interested young men submitted applications to local public welfare offices and regional Veterans Administration facilities. From those applicants, the Department of Labor selected "junior" enrollees, or unemployed single men between the ages of 18 and 23.3 The Veterans Administration selected veterans, without regard to age or marital status.4

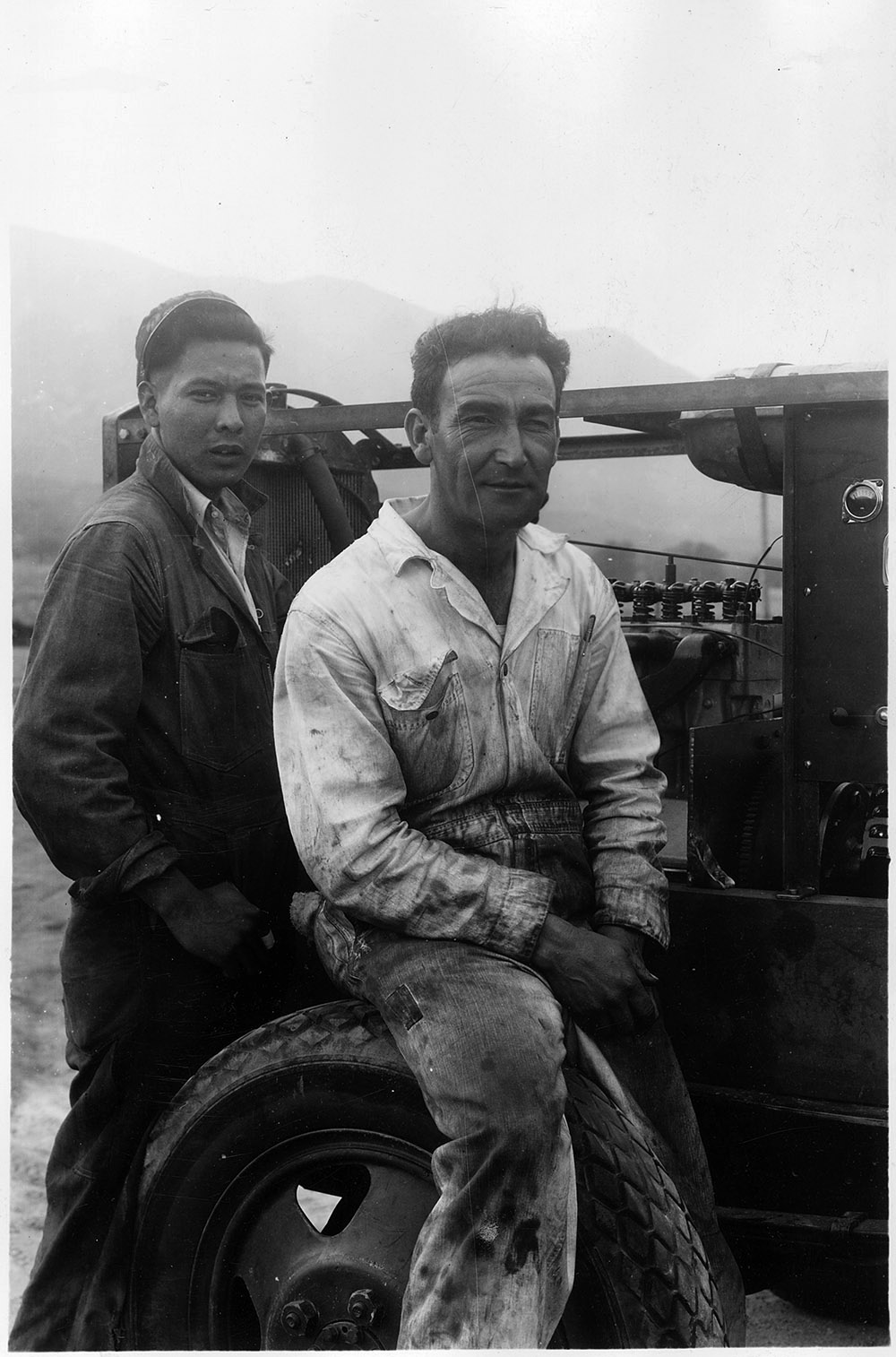

Men selected as enrollees were transported to camps, where they lived for the entirety of their service. Enrollees served in the CCC for six months with the opportunity to re-enroll for up to two years. They were assigned tasks on projects managed by the Department of the Interior and the Department of Agriculture. The War Department oversaw the transportation, administration, conditioning, discipline, medical care, entertainment, religious activities, and work detail of enrollees.5

The War Department was also responsible for maintaining each enrollee's Individual Record, CCC Form No. 1, which contains the answers to questions posed to enrollees from induction through discharge. Individual Records, now maintained on reels of microfilm, are available to the public.6

The answers given to the basic questions posed on an Individual Record can prove invaluable to today's researcher. In addition to standard inquiries such as name, address, date of birth, place of birth, and physical appearance are questions regarding citizenship as enrollees had to be either naturalized or "native born" citizens of the United States. Some of the records also include an application form for emergency relief or a Civilian Conservation Corps Enrollee's Cumulative Record, CCC Ed. Form No. 2. Both the Individual Record and the Cumulative Record contain information about past educational and occupational experience, including military service.

Because enrollees had to be able-bodied to perform physical labor, the records contain a detailed account of their medical, dental, physical, and mental health. According to War Department regulations, each enrollee had to possess relatively good eyesight and hearing, a heart able to "stand the stress of physical exertion," and intelligence that would allow one to "understand and carry out instructions relative to the work demanded." Additionally, each enrollee had to "be able to transport himself by walking and perform manual labor."7

Army, Navy, and civilian physicians administered medical care. Additionally, two enrollees per company were trained in first aid procedures.8 CCC enrollees' medical records, which may document symptoms, medical treatments, diagnoses, and daily readings of vitals, are housed at the National Archives at St. Louis.

Each enrollee's Individual Record also includes information about work sites and projects. The Departments of the Interior and Agriculture designed and planned work projects in every state, the District of Columbia, and the territories of Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Hawaii, and Alaska. An enrollee could be assigned to a variety of projects during his 6- to 24-month stint. Experienced government employees from each agency supervised the projects.9

Enrollees worked on more than 150 different tasks, including reforestation, soil conservation, fish and wildlife aid, the construction of recreational areas, and emergency rescue.10 After one year, the CCC had improved many acres of forest, erected miles of telephone lines, and constructed thousands of dams to control erosion. Between 1933 and 1942, enrollees had fought natural disasters such as floods, blizzards, forest fires, tornadoes, and hurricanes and provided assistance for victims of these catastrophes.11

For their efforts, enrollees were granted an allowance, a portion of which was sent home to a designated dependent. Enrollees received $30, assistant leaders $36, and leaders $45 per month; $22 or more was allocated as the allotment. Veterans were mandated to designate three-fourths of their pay as the allotment.12 Over the course of the CCC's existence, approximately $72.5 million was given to dependents through allotments.13 Individual Records include information about the allowances, deposits made to enrollees accounts, allotment amounts, and allotment recipients (and their addresses).

In general, enrollees worked 40-hour weeks, eight hours a day, Monday through Friday. They were granted leave and holidays. After work hours, enrollees could engage in sports activities, benefit from libraries, enjoy motion pictures, and attend religious services that were available to all faiths. Furthermore, the Office of Education offered educational opportunities, which were also recorded on each enrollee's Individual Record.14

Individual Records also include discharge information (honorable, dishonorable, or administrative). Enrollees who received a dishonorable or administrative discharge or any alternative disciplinary action were put on trial. If an enrollee was the subject of disciplinary allegations, his Individual Record would include a Record of Hearing along with supporting documentation. Upon release from the CCC, enrollees received a Certificate of Discharge. Only a few certificates, however, are found in the archival holdings.

The Official Personnel Folders of individuals who worked as federal employees under the War Department, Department of the Interior, Department of Agriculture, or the Office of the Director as administrative personnel or project leaders are also publicly available. These files contain a variety of information including applications, correspondence to and from the employees, changes in status, and termination documents.

Works Progress Administration

President Roosevelt established the WPA on May 6, 1935.15 Like the CCC, the WPA was intended to provide work to those in need of relief and to improve the welfare of the nation. Individuals receiving relief had to be "certified" by an approved relief agency. Certified individuals received priority and made up 95 percent of the WPA workforce, but individuals not receiving relief were also selected to work for the WPA.16

While both men and women were assigned jobs, only one person per household could work for the WPA at any given time.17 Applicants had to be over the age of 18, and there was no upper age limit. Students between the ages of 16 and 24 could apply for work with the WPA's National Youth Administration (NYA). The WPA also employed individuals with disabilities as long as their past experience qualified them for work other than manual labor.18

The National Archives at St. Louis holds the records of the WPA, NYA, and the WPA's earlier incarnation, the Civil Works Administration, which functioned between November 9, 1933, and March 31, 1934. WPA records do not consistently reveal as much background information as those related to CCC enrollees; however, they reveal a glimpse of what yesterday's Americans constructed, demolished, and recorded.

The diverse forms now exist primarily as microfilmed slips of paper. The majority of WPA personnel records consist of

- Notice to Report to Work on Project and Reassignment Slips, which indicate the time, date, location, and nature of the assigned duty;

- Reclassification Slip and Notice of Change in Work Status, which note changes in wage rate, hours worked, title, or certification status; and

- Notice of Termination of Employment.

The records of workers who received relief, or were "certified," may also include a Certification of Eligibility, Notice of Case Change, Cancellation of Certification of Eligibility, or Worker's Statement of Family Resources. The records of administrative personnel primarily contain correspondence.

In order to grant work opportunities to as many people as possible, certified workers were terminated after 18 months, with the exception of those who were blind, veterans, widows of veterans, or the wives of "unemployable" veterans. After 20 days, terminated workers could reapply.19

On average, WPA employees worked 130 hours a month. They were not permitted to exceed 8 hours work a day or 40 hours a week. Work hours could be exceeded in the case of an "emergency concerning public welfare," "to protect work already done on a project," or to accomplish work on projects approved for military or naval purposes, which became a primary goal as U.S. involvement in World War II approached.20

The projects were wide ranging. The Division of Employment assigned occupational classifications with available individuals' skills and project types and needs. While most people were assigned projects within a reasonable travel distance from their homes, some were assigned to work camps.21

WPA workers built ski lodges, airports, schools, hospitals, public buildings, golf courses, zoos, campgrounds, and sites such as the Riverwalk in San Antonio, Texas. Other WPA employees sewed clothing, made mattresses, grew medicinal herbs for pharmaceuticals, taught classes to children and adults, provided school lunches to malnourished children, delivered books by "packhorse libraries" to people in remote locations, and established electricity in rural locations.22

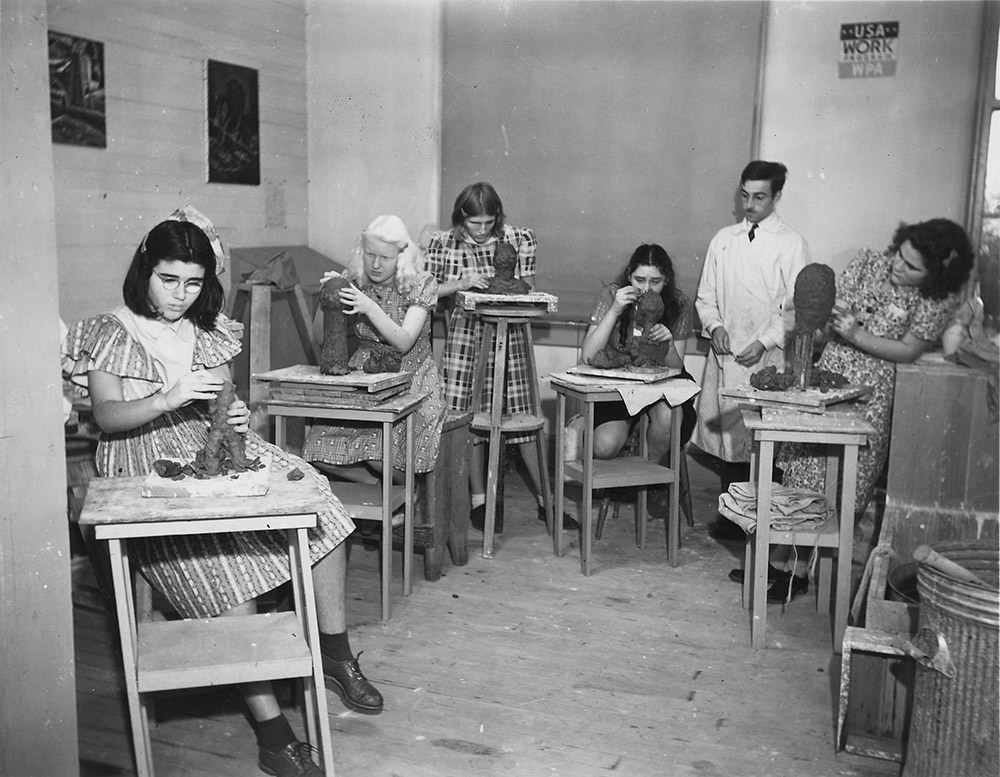

Federal Project Number One was created under the WPA to entertain and enlighten the public through various forms of art. "Federal One"was a continuation of the Public Works of Art Project under the Department of the Treasury and contained five divisions—Historical Records Survey, Federal Writers' Project, Federal Theatre Project, Federal Art Project, and Federal Music Project.

Federal One employed skilled artists, writers, actors, and musicians. Artists performed classical music and (often uncensored) plays; created sculptures, paintings, and murals; preserved regional folk art; and compiled slave narratives, local histories, state guides, folktales, and surveys of historic sites and buildings.23 As World War II commenced, artists' duties were transferred to war-related projects, including designing posters and camouflage.

National Youth Administration

Established on June 26, 1935, the NYA was the federal government's answer to the problem of "restless youths." The NYA functioned under the WPA to continue the education and promote the employment of high school and college-age students. Those still attending school received part-time work, and those who had dropped out of school performed community-related duties. The program also focused on assisting African American youths.24

The records of youth workers and administrative employees who worked between 1935 and July 1, 1939, may exist on microfilm reels that also contain WPA records. The records of NYA administrative employees who were separated from service between July 1, 1939, and 1943 are paper files that consist primarily of leave and pay information.

Because the nation began to redirect its efforts and resources toward the demands of war, the CCC was disbanded on June 30, 1942, and the WPA ceased operation on June 30, 1943. Having offered employment to 2.5 million CCC enrollees and 8 million individuals through the WPA, the public emergency work referenced on the 1940 federal population census not only provided for Americans monetarily but also gave experience to individuals who would continue in the workforce and the military. The invaluable work performed by these agencies can still be seen today in murals, National Parks, roadways, and a variety of other enhancements.

Requesting Records

In order to obtain copies of personnel records related to the CCC, WPA, or NYA, please send a written request after October 1, 2012, to National Archives at St. Louis, Attn: Archival Programs, P.O. Box 38757, St. Louis, MO 63138, or send an email to stl.archives@nara.gov. In your request, please include the full name and date of birth of the requested individual. If the person worked for the WPA, include a city and state of employment. If you are looking for medical or fatality forms for a CCC enrollee, please include this information with the request. Since many individuals have similar names, please provide as much information as possible (for example: birthplace, parents' names, and years of employment).

If the National Archives locates a record, you will receive an invoice for a copy of it. The copy fees are $20.00 for a record under five pages and $60.00 for a record that is six pages or more. Please note that CCC and WPA records are on microfilm, and copies of these records are sometimes difficult to read. Some personal information is redacted in accordance with the personal privacy exemption of the Freedom of Information Act (5 U.S.C. 552 (b) (6)).

Ashley Mattingly is an archivist with the National Archives at St. Louis whose primary focus is civilian personnel records. She started working for the National Archives in 2007 as a preservation technician and as an archivist in 2008. She received her master of library and information science degree from the University of Southern Mississippi and a B.A. in history from Washington College in Maryland.

Notes

1 National Archives and Records Administration, "1940 Federal Population Census" (www.archives.gov/research/census/1940/general-info.html#questions).

2 Franklin D. Roosevelt, Second Fireside Chat (May 7, 1933), The American Presidency Project, (www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=14636#axzz1kyZMhpWh).

3 As of July 5, 1939, this selection was made by the Director of the Civilian Conservation Corps. War Department, Civilian Conservation Corps Regulations (Washington, DC: War Department, September 28, 1938), Changes, No. 13, 30, pp. 1, 3a.

4 War Department, War Department Regulations, Relief of Unemployment, Civilian Conservation Corps (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, May 15, 1935), p. 9.

5 Ibid., p. 4.

6 Personnel records for persons assigned to public emergency work may be found at the National Archives at St. Louis.

7 War Department Regulations, p. 120.

8 Ibid., pp. 79–80.

9 Federal Security Agency, The Civilian Conservation Corps: What It Is and What It Does (Washington, DC: June 1940), p. 5.

10 Ibid.

11 John A. Salmond, The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933–1942: A New Deal Case Study (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1967), pp. 46, 54–55.

12 War Department Regulations, pp. 9, 17.

13 Salmond, The Civilian Conservation Corps, p. 55.

14 War Department Regulations, pp. 17, 26, 111–116.

15 The Works Progress Administration was renamed the Work Projects Administration in 1939.

16 Federal Works Agency, Works Projects Administration, Manual of Rules and Regulations, Volume III, Employment (Washington, DC), p. 3.4.013.

17 Nick Taylor, American-Made: The Enduring Legacy of the WPA: When FDR Put the Nation to Work (New York: Bantam Books, 2008), p. 197.

18 Manual of Rules and Regulations, p. 3.2.028.

19 Ibid., p. 3.5.003.

20 Ibid., p. 3.6.001.

21 Ibid., p. 3.4.003.

22 Taylor, American-Made, pp. 2–3, 222, 330.

23 Ibid, pp. 186, 293.

24 Sharon M. Hanes and Richard C. Hanes, Great Depression and the New Deal: Primary Sources (Detroit: U-X-L, 2003), pp. 215–217.