The Revolutionary Summer of 1862

How Congress Abolished Slavery and Created a Modern America

Winter 2017–18, Vol. 49, no. 4

By Paul Finkelman

© 2017 by Paul Finkelman

Secession and the Civil War were about slavery and race.

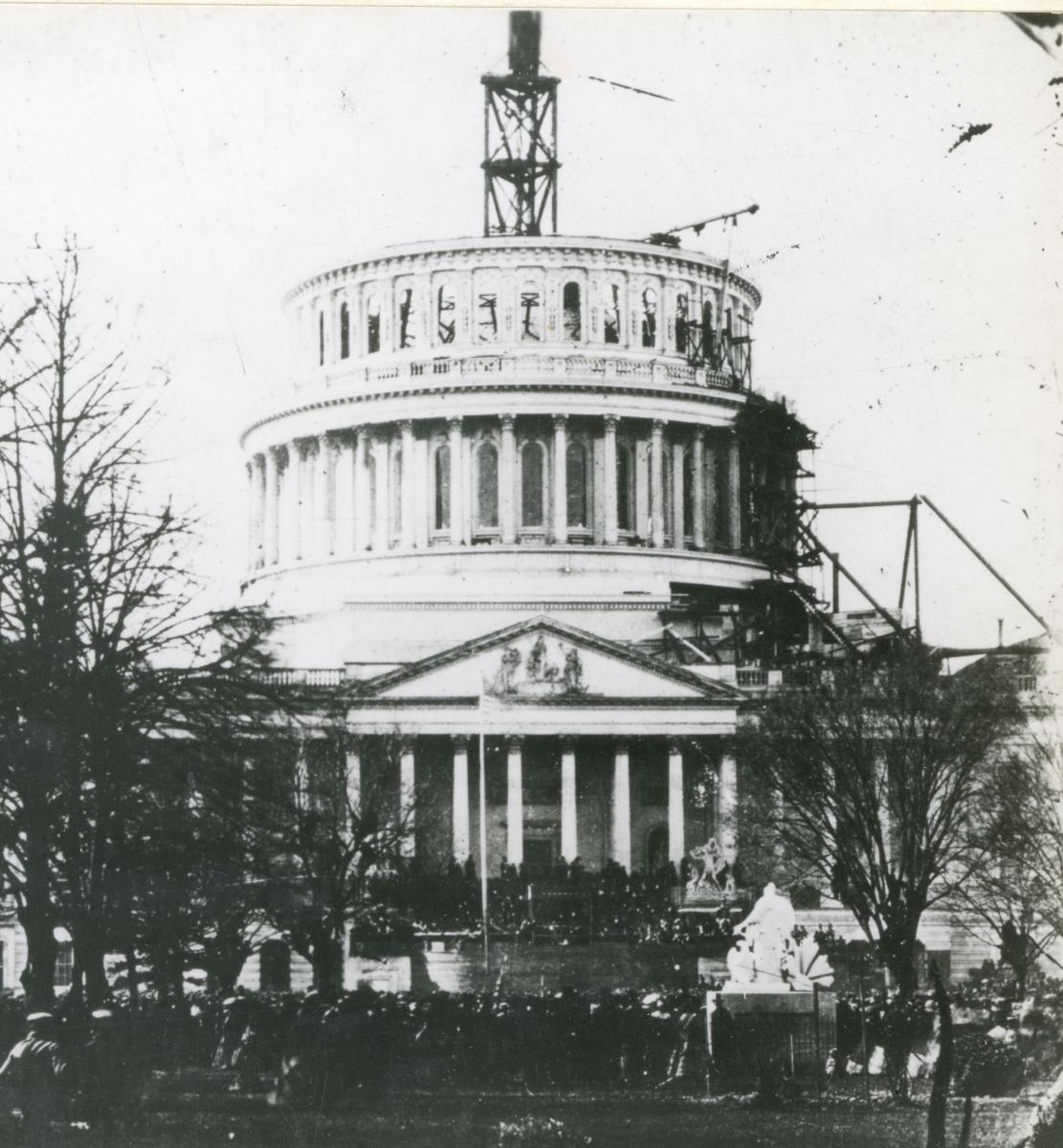

In his second inaugural address, Abraham Lincoln recalled, “All knew that” the “peculiar and powerful interest” in slaves “was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.”

Alexander Stephens, the Confederate vice president, made virtually the same point: “Our new government is founded . . . its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

Focused on preserving the nation at the time of his first inaugural address, Lincoln promised to do nothing to harm slavery: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

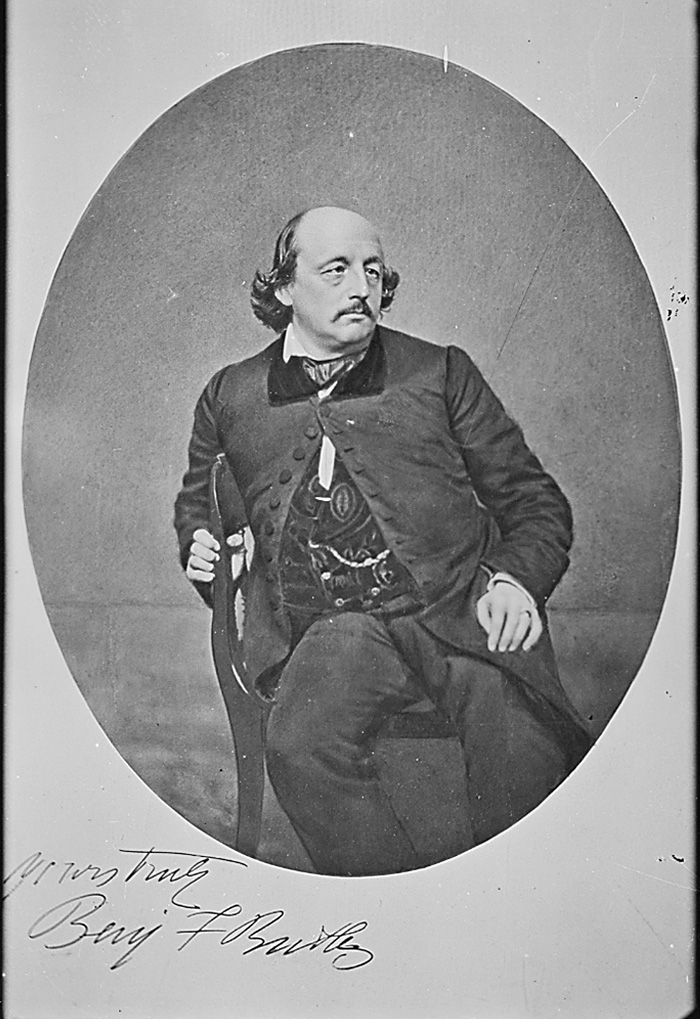

Wartime events, however, quickly overtook policy and forced the administration to take a position on slavery and emancipation. The process of ending slavery began with a small event: the arrival at Fortress Monroe in Virginia of three slaves owned by Confederate Col. Charles Mallory. The next day, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler faced what was perhaps the most surrealistic spectacle of the war, when Confederate Maj. M. B. Carey appeared under a flag of truce, demanding the return of Mallory’s slaves. Carey, acting as Mallory’s agent, told Butler he was obligated to return the slaves under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

A lawyer before the war, Butler concluded that Mallory’s slaves were “contrabands of war” and could be taken from the enemy. Butler told Carey “that the fugitive slave act did not affect a foreign country, which Virginia claimed to be, and she must reckon it one of the infelicities of her position that in so far at least she was taken at her word.” With a marvelous touch of irony, Butler offered to return the slaves to Mallory if he would come to Fortress Monroe and “take the oath of allegiance to the Constitution of the United States.” But Butler knew this would never happen, so the former slaves were “contrabands of war” and remained free.

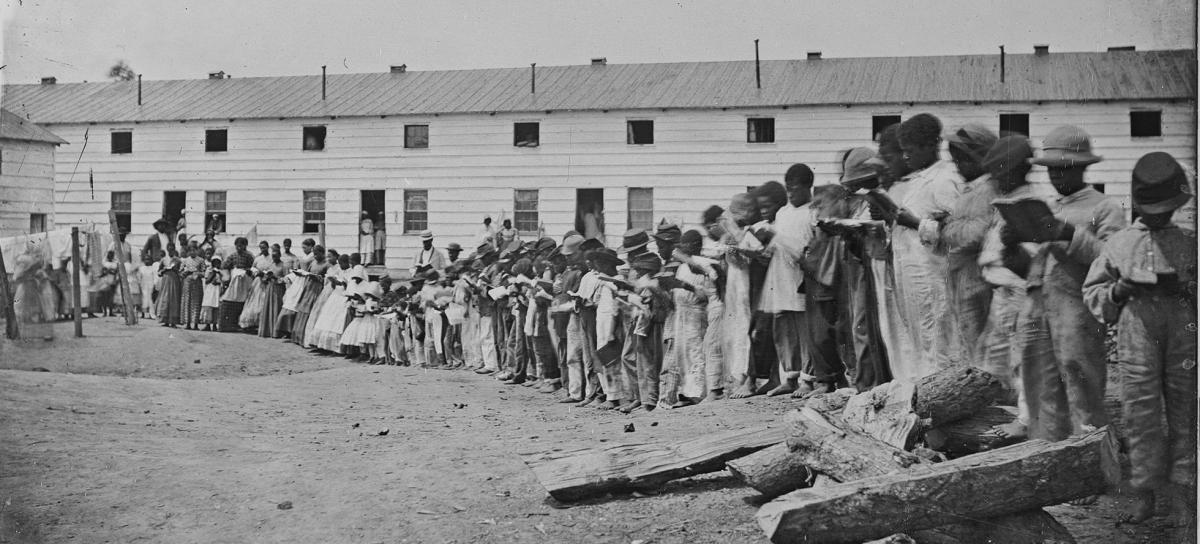

Butler hired these three “contrabands” to work for the Army, turning slaves into free laborers. By August there were more than 1,000 runaway slaves—newly minted contrabands—at Fortress Monroe and other U.S. Army camps. The War Department had endorsed Butler’s action, Lincoln admiringly joked about “Butler’s fugitive slave law,” and Congress had passed the First Confiscation Act, authorizing the government to seize slaves used by the Confederate Army. This law opened the door to more attacks on slavery and began turning the war for the Union into a war for freedom.

Thus, by the time Congress adjourned in August 1861, there was a de facto emancipation policy, but it only involved slaves used by the Confederate Army or those who could reach U.S. Army lines—a very small percentage of the three and a half million slaves in the Confederacy. But if slaves managed to reach U.S. lines, the Army could legally give them sanctuary.

Eventually, Lincoln used the contraband theory as the basis of the Emancipation Proclamation. If Butler could emancipate three slaves as a military measure, then Lincoln ultimately determined he could emancipate three million slaves for the same purpose. But before he could accomplish this, Congress would move against slavery and racism in a variety of ways.

Congress Reassembles as Union Forces Triumph

Congress reassembled on December 2, 1861, meeting until July 17, 1862. As historian James McPherson noted in his Pulitzer Prize–winning book Battle Cry of Freedom, this was “one of the brightest periods of the war for the North.” In November 1861 Adm. Samuel F. Du Pont seized the South Carolina Sea Islands naval base at Port Royal, bringing the war to the Confederate heartland. By the end of April, the Navy and Army had captured or sealed off every Confederate port on the Atlantic except Charleston, South Carolina, and Wilmington, North Carolina.

In the west, the United States won a series of crucial victories that completely altered the military and political situation in the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. In February 1862, troops under Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant captured Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in Tennessee. By June a good piece of Tennessee, as well as the cities of New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Natchez, and smaller towns in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas, were firmly under United States control.

As military successes multiplied, the Republican Congress began to remake the nation, changing race relations, attacking slavery, and creating the political and structural infrastructure of the modern United States. Congress’s revolution in race relations encouraged Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and led to the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. In the summer of 1862, Congress abolished slavery in the District of Columbia and the federal territories, authorized the confiscation of slaves owned by Confederates, formally freed all slaves who escaped to the United States Army, prohibited the Army from returning fugitive slaves, authorized the enlistment of black soldiers, and created public schools for African American children in the District of Columbia.

The timing of these laws shows that moves against slavery were not the result of desperation or fear of losing the war. Rather, Congress moved against slavery in the wake of military success, as did Lincoln when he issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation after the major victory at Antietam.

Taken together these laws reveal the revolutionary change in federal law that began with the First Confiscation Act and continued through the end of Reconstruction. This was all possible because of the war, the ideology of the Republican Party—later known as the Party of Lincoln—and the absence of most proslavery Southerners from Congress. The heart of this revolution came in the summer of 1862.

In March, Congress first moved against slavery with “An Act to Make an Additional Article of War,” prohibiting the Army from returning fugitive slaves to any masters and providing a court-martial for any officers allowing this to happen. The law applied to all slaves, including those from the loyal slave states, not just fugitives from the Confederacy.

Congress Broadens Its Ban on Slavery in Loyal States

In early April, the House and Senate passed a stunning joint resolution: “That the United States ought to cooperate with any State which may adopt gradual abolishment of slavery, giving to such State pecuniary aid, to be used by such State in its discretion, to compensate for the inconveniences, public and private, produced by such change of system.” Never before had Congress attempted to interfere with slavery in the states where it already existed or taken the position that slavery ought to be abolished anywhere. Now it was actually offering to pay the costs of ending bondage in the loyal slave states—Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri.

Congress then applied this logic to the national capital, with an “Act for the Release of Certain Persons Held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia.” For the first time in history, an act of Congress emancipated slaves. Previous limitations on slavery, like the Northwest Ordinance, had only prevented slavery from spreading to new territories and did not actually free existing slaves. Here Congress passed a law, the President signed it, and slavery ended.

Congress recognized that slaves were “property” and provided modest compensation for the owners of slaves, because the Constitution prohibited taking property without just compensation. Although the law immediately freed all slaves in the District, the compensation process was set to take place over a period of nine months. Thus, masters lost the use of their slaves immediately but were not compensated until later. Compensation was denied to anyone who was not “loyal” or had aided the rebellion. The law also punished kidnapping of the now free black population and repealed existing laws “inconsistent with the provisions of this act.” With the stroke of a pen, slavery ended in the nation’s capital.

A month later, Congress created publicly funded schools for blacks and gave control of them to the secretary of the interior, preventing local officials, in what essentially was a southern city, from interfering with or harming the black schools. From a modern perspective, this was an inadequate, segregated school system; from the perspective of 1862, it was an enormous step forward for African Americans. This became the first public school system for blacks south of the Mason-Dixon line.

Equal Protection Given to Ex-Slaves

The final section of this law was even more remarkable—and stunningly progressive, even by modern standards. The law provided:

That all Persons of Color in the District . . . shall be subject and amenable to the same laws and ordinances as free white persons are or may be subject or amenable; that they shall be tried for any offences against the laws in the same manner as free white persons are or may be tried for the same offences; and that upon being legally convicted of any crime or offences against any law or ordinance, such persons of color shall be liable to the same penalty or punishment, and no other, as would be imposed or inflicted upon free white persons for the same crime or offence; and all acts or parts of acts inconsistent with the provisions of this act are hereby repealed.

This provision was a precursor of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and was a major step toward racial equality. This was the first provision of its kind: a federal promise of equal protection of the law for blacks charged with crimes.

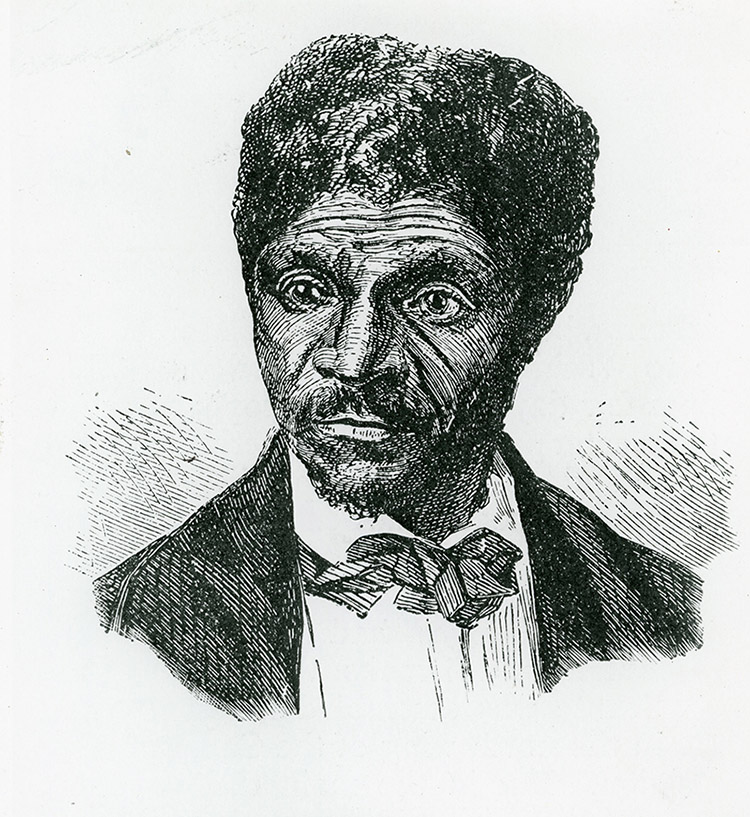

Next, Congress ended slavery in the territories. In Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) Chief Justice Roger B. Taney held that Congress had no authority to end slavery, or even prohibit it, in the territories. But ending slavery in the territories was a major component of the Republican program, and almost all Republicans agreed that Taney’s constitutional analysis was dicta, wrong, and insulting.

Republicans thus acted on their theory of the Constitution, ignored Taney, and flatly prohibited slavery “in any of the Territories of the United States now existing, or which may at any time hereafter be formed or acquired by the United States.” With one sentence, Congress undid a key aspect of the holding in Dred Scott and reversed more than seven decades of public policy on slavery in the territories.

Unlike their counterparts in the District of Columbia, masters in the territories received no compensation for their emancipated slaves. This seemed to be a clear taking of “private property . . . for public use, without just compensation,” in violation of the Fifth Amendment. However, Republicans argued that slavery was “contrary to natural right,” inconsistent with the law of nature, and “[w]herever it exists at all, it exists only in the virtue of positive law.” Senator Charles Sumner captured the essence of this in the title of his 1852 speech, “Freedom National; Slavery Sectional.” Republican leaders argued that because slavery could only exist where there was positive law, no one could be a slave in the territories because Congress never passed laws creating slavery there. Thus, compensation was unnecessary.

New Laws Create a Modern America

In the summer of 1862, Congress spent some of its energy on slavery-related issues that were tangential to the war effort but symbolically important to the revolution in race relations. In June, Congress authorized formal diplomatic relations with Haiti and Liberia. Black envoys from Haiti or Liberia could come to Washington and have diplomatic immunity and participate in diplomatic gatherings. This was another example of the new nation the Republicans were creating with the Southerners no longer in Congress. In June, the Senate ratified a treaty with Great Britain to help suppress the illegal African slave trade, and in July, Congress authorized the creation of judges and arbitrators to implement the treaty. Previous Presidents would not have negotiated such a treaty, nor would the Senate, with its large number of Southerners, have ratified it.

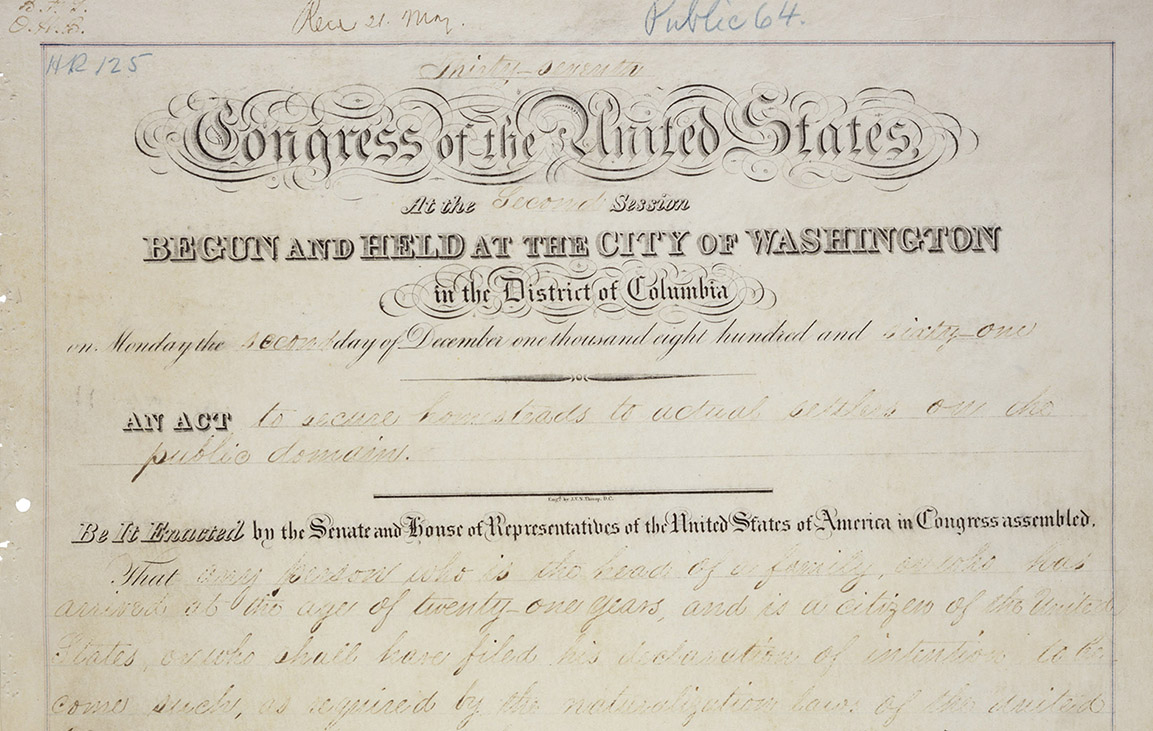

In the summer of 1862—with most Southerners absent and unable to block progressive legislation—Congress also passed a number of laws indirectly connected to the struggle against human bondage. Congress created the Department of Agriculture, passed the Homestead Act, upgraded public education in the District of Columbia, passed legislation for the creation of the transcontinental railroad, created land grant colleges, and passed laws to suppress polygamy in the Utah territory. Southerners had previously blocked all this legislation because it would lead to new free states, help the northern economy, or indirectly threaten slavery.

At first glance, polygamy hardly seems like an issue affected by secession or slavery. But opposition to polygamy was tied to proslavery and antislavery politics. Southerners did not advocate polygamy but feared that regulation of any “domestic institutions” in a territory or state would set a precedent for interfering with slavery. Thus, they opposed any federal law regulating marriage in Utah.

While never explicitly part of the political debate, Southerners were particularly sensitive about any discussion of sexual morality because so many Southern white men—including many in Congress and the executive branch—had fathered children with their slaves while others, like Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina or former Vice President Richard M. Johnson, famously kept a slave mistress in Washington.

On the other hand, in 1856, the Republican Party platform condemned both slavery and polygamy: “Resolved: That the Constitution confers upon Congress sovereign powers over the Territories of the United States for their government; and that in the exercise of this power, it is both the right and the imperative duty of Congress to prohibit in the Territories those twin relics of barbarism—Polygamy, and Slavery.” Having prohibited slavery in the territories the previous month, Republicans could now end the other “relic of barbarism” in the territories, polygamy.

Ex-Slaves Welcomed into Army Service

The final revolutionary acts of the summer of 1862 were the Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act. The Second Confiscation Act provided for the emancipation of slaves owned by Confederate officials and military officers, anyone convicted of treason against the United States, anyone who might “assist, or engage in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States,” or who gave “aid and comfort to, any such existing rebellion or insurrection” or “anyone who having held an office of honor, trust, or profit in the United States” who then held “an office in the so-called confederate states of America,” and anyone living in the loyal states who gave any aid or comfort to the Confederacy. All slaves escaping to the Army, or captured by the Army, who were owned by anyone who supported the rebellion were “forever free of their servitude, and not held as slaves.” Slaves escaping into the United States, or within the United States, would only be returned to masters who had “not borne arms against the United States in the present rebellion, nor in any way given aid and comfort thereto.”

However, under this law no member of the United States Army or Navy was permitted to return a fugitive slave. Most of these provisions required some sort of judicial hearing to prove that the slaveowner had committed treason or supported the rebellion. Nevertheless, it is possible to imagine summary proceedings to liberate slaves owned by Confederate masters.

Congress further empowered the President “to employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of this rebellion” and “organize and use them in such manner as he may judge best for the public welfare.” Presumably, this would have included enlisting them in the Army. In a sop to conservatives, the law allowed, but did not require, the President “to make provision for the transportation, colonization, and settlement, in some tropical country beyond the limits of the United States, of such persons of the African race, made free by the provisions of this act, as may be willing to emigrate.” A similar provision had been in the D.C. Emancipation Act, but that one included some funding for the expatriation of former slaves. This law contained no funding. But none of this really mattered. President Lincoln never took any steps to move blacks outside the United States, and no blacks ever stepped forward to seek transportation.

The Militia Act of 1862 resolved any ambiguity about the enlistment of black troops. The Militia Act of 1792 had limited service to “every free able-bodied white male citizen,” but the 1862 act provided for “the enrolment of . . . all able-bodied male citizens between ages of eighteen and forty-five.” The word “white” was now gone. This was a quiet and dramatic change in American law. It theoretically meant that blacks could now be in the Army. In Dred Scott, Chief Justice Taney had held that blacks were not citizens of the United States, but at this point Congress refused to give any deference to Taney’s decision.

In August 1862, U.S. Begins Enlisting, Training Blacks

Any doubts about the enlistment of blacks were resolved by language authorizing the President “to receive into the service of the United States, . . . persons of African descent, and such persons shall be enrolled and organized under such regulations, not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws, as the President may prescribe.” In August, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton authorized Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, headquartered in Hilton Head, to begin enlisting and training black troops.

The next section of the Militia Act was even more far reaching, providing:

That when any man or boy of African descent, who by the laws of any State shall owe service or labor to any person who, during the present rebellion, has levied war or has borne arms against the United States, or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort, shall render any such service as is provided for in this act, he, his mother and his wife and children, shall forever thereafter be free, any law, usage, or custom whatsoever to the contrary notwithstanding: Provided, That the mother, wife and children of such man or boy of African descent shall not be made free by the operation of this act except where such mother, wife or children owe service or labor to some person who, during the present rebellion, has borne arms against the United States or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort.

Presumably, every slaveowner in the Confederacy had given “aid and comfort” to the rebellion, and from this point forward, any slave in a Confederate state joining the Army would bring freedom to his mother, wife, and children. Even before Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Congress was dismantling southern slavery.

Unfortunately, Congress did not provide for the freedom of the fathers, grandparents, or siblings of slaves. Nor did Congress deal adequately with salaries for black soldiers. Under the Militia Act, blacks received the same pay as laborers—10 dollars a month—rather than the 13 dollars paid to white soldiers. In addition, the government held back three dollars a month for clothing. Congress may have assumed that former slaves would be unable to manage their own affairs (and purchase their own clothes) and thus the military had to do it for them. The paternalistic and racist implications of such an analysis are obvious. As James McPherson notes, the unequal salary was a “concession to prejudice.” Black leaders, black soldiers, and their white allies roundly condemned the salary inequity. Congress eventually equalized pay and gave black soldiers some back pay.

But, even with the discrimination in pay, the Militia Act of 1862 was a remarkable assault on slavery. Throughout the Confederacy—and in the loyal slave states—the U.S. Army could recruit slaves to fight for the nation and against slavery. Slaves joining the Army would bring freedom to many of their family members, and this freedom was enforced by the Army. Unlike the Emancipation Proclamation, the Militia Act combined with the Second Confiscation Act undermined the loyal slave states as well as the Confederacy.

The war was now clearly a crusade against slavery. In the next three years, Congress continued to pass laws that challenged slavery and racism, repealing the fugitive slave laws, banning segregation on streetcars in the District of Columbia, passing the 13th Amendment, and creating the Freedmen’s Bureau. These, and many other laws, were a continuation of the radical changes that took place in the Revolutionary Summer of 1862.

Paul Finkelman is the president of Gratz College in Melrose Park, Pennsylvania. He wrote this article while holding the Fulbright Chair in Human Rights and Social Justice at the University of Ottawa. He earned a B.A. in American studies from Syracuse University and a Ph.D. in history from the University of Chicago. He is the author of more than 200 scholarly articles and author or editor of more than 50 books. His most recent book, Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s High Court, was published by Harvard University Press in 2018.

Note on Sources

This article is excerpted from a much longer chapter in Paul Finkelman and Donald R. Kennon, eds., Congress and the People’s Contest: The Conduct of the Civil War (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2018).

Most of this essay is based on the laws and resolutions passed by Congress in 1861 and 1862. They are all found in volume 12 of the United States Statutes at Large. The Statutes at Large are conveniently available on the website of “A Century of Lawmaking for the New Nation” at the Library of Congress (memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwsl.html.)

Other primary sources I have used include: the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion; Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vol. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953); Henry Cleveland, Alexander H. Stephens, in Public and Private: With Letters and Speeches, Before, During, and Since the War (Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, 1866); Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book (Boston: A. M. Thayer & Co., 1892),

My secondary sources include: Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York, 2010); James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford, 1988); David Dudley Cornish, The Sable Arm: Negro Troops in the Union Army, 1861–1865 (New York: W.W. Norton 1966); Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Paul Finkelman, Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2014).