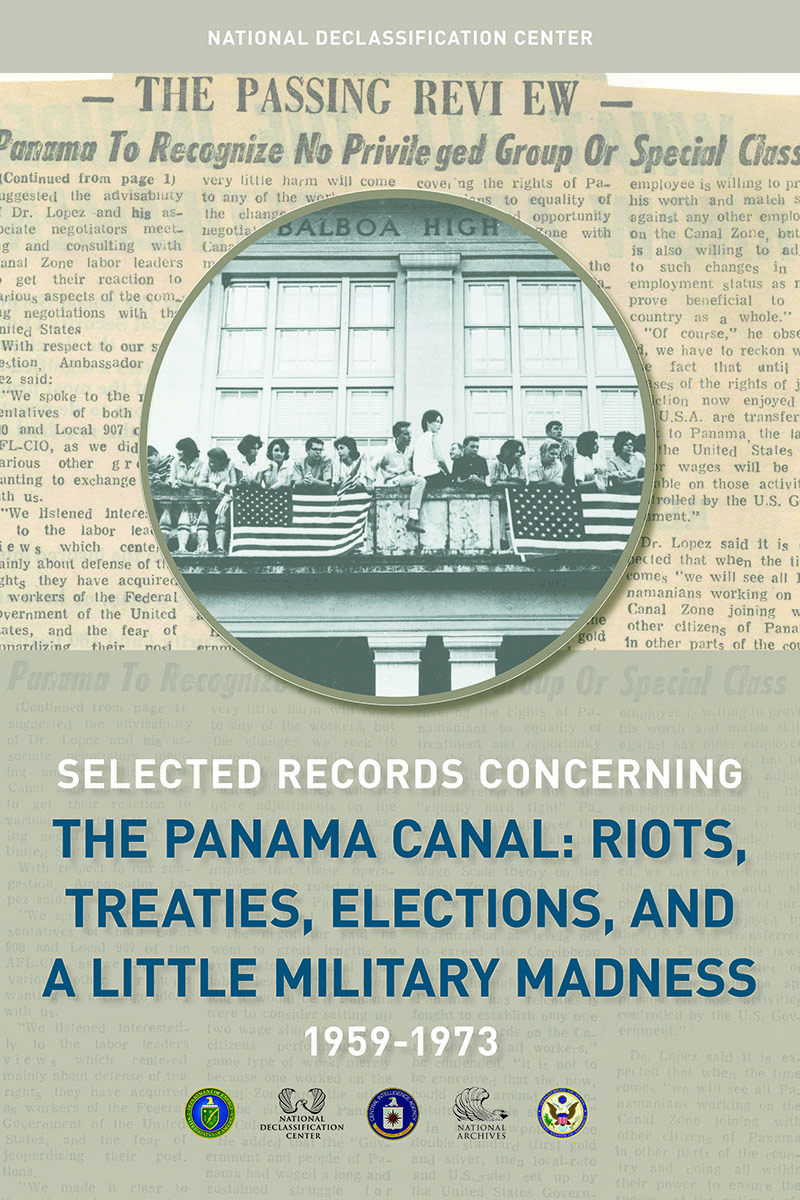

The Panama Canal: Riots, Treaties, Elections, and a little Military Madness, 1959-1973

Introduction

Introduction

In August 2014, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) honored the 100th anniversary of the construction of the Panama Canal by posting blogs on various records relating to Canal employees and to U.S. and Panamanian relations. 2015 marked the 100th anniversary of the official celebration of the completed construction of the Canal by the United States. Although the Canal was officially opened to shipping on August 15, 1914, few realize that the official celebration had to be postponed due to the start of World War I a few weeks later. The official recognition of its completed construction was not celebrated until March 1915 at the San Francisco Exposition.

To celebrate this official recognition, the National Declassification Center (NDC) of NARA focused on recently declassified records in our custody that celebrate what the American Society of Civil Engineers has named the Seventh Civil Engineering Wonder of the World, the Panama Canal. The majority of Americans may have heard of the Panama Canal but few may know the United States’ role in its construction and maintenance, let alone the part that it played in our foreign relations with Panama. Debate continues to swirl around issues of why the U.S. turned the Canal over to Panama, Panamanian distrust of the U.S. Government in general, and the imperialistic image associated with U.S. employees that administered and lived in the Canal Zone. Many historians have examined our early pre and post construction relations with Panama but not many have examined the period just prior to the Canal turnover. The records that have been recently declassified focus on that pre turnover era and may assist U.S. citizens as well as scholars in understanding the story that led to one of the biggest changes in U.S. foreign policy since the Canal was built.

Project Background

Classified records series relating to Panama were identified, surveyed, and chosen to be declassified from Record Group 59, General Records of the Department of State, and Record Group 84, Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State. The records were reviewed and declassified. From the declassified documents, a selection of documents were chosen from these record groups to illustrate the kind of information that can be found in our holdings.

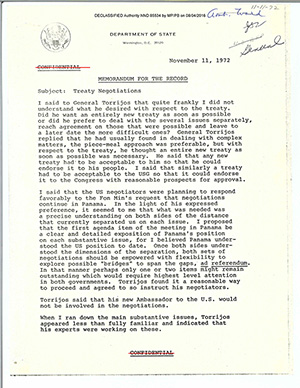

The declassified records consist of memorandums, correspondence, telegrams, reports and scattered photographs concerning such matters as U.S.-Panamanian Canal relations, riots and student protests, diplomatic treaties, development of foreign policy from President John F. Kennedy to President Gerald R. Ford, internal political affairs, economic issues, the defense of the Canal and U.S. military presence, a discussion of a new sea level canal, and Panamanian sovereignty over the Canal and the Canal Zone.

The records provide a significant insight into the transition of the Canal from U.S. control to Panamanian jurisdiction just as older unclassified records provide insight into the beginnings of the Canal’s history. The political motivations, economic issues, and nationalistic fervor that led to the tension between the U.S. and Panama are widely discussed in these recently declassified records.

The images selected for this web page represent only a handful of the newly declassified records found in NARA’s holdings that focus on U.S.-Panamanian relations. When more related records are identified and declassified, they will be added to this web page.

Searching/Finding the Records

To locate relevant records in NARA’s custody, the researcher should be familiar with the missions of various U.S. government agencies and how they intersect with their topic. The researcher can use this strategy to narrow their topic before arriving at NARA. The online National Archives Catalog is available to assist researchers in locating the specific records that concern their topic. Placing various key words in the search box of the catalog along with Panama Canal has proven to be useful when searching through the catalog. For example, input such as “Panama Canal and naval operations” or “Panama and U.S. relations” resulted in related “hits” in the National Archives Catalog.

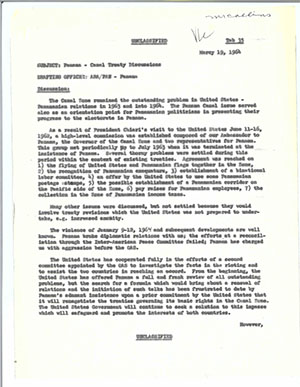

The Canal and the Panamanians

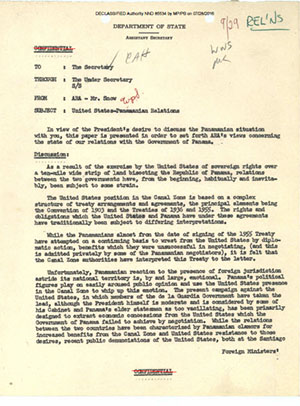

The frayed relations between the U.S. and Panama began almost immediately after the signing of the 1903 Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty that allowed the U.S. to build and maintain the Panama Canal on the Isthmus of Panama. Panama was established as a country, with U.S. assistance, shortly before the treaty was signed in 1903. Over the years, the Panamanians sought to obtain more equitable provisions from the original treaty than the U.S. was willing to concede. The two countries addressed these issues through adjustments to the original agreement during the treaty negotiations of 1936, 1942, and 1955.

The need for continued negotiations was due to what the Panamanians viewed as improper interpretations by the U.S. of the original treaty. These misinterpretations revolved around matters such as the sovereignty issue, the “in perpetuity” clause, flying the Panamanian flag in the Zone, the importing of third party goods into the Zone, the exclusion of Panamanian goods and services from Zone markets, and discrimination against Panamanians working in the Zone. The U.S. on the other hand felt that the Panamanians viewed the Canal as “their meal ticket” and exploited it accordingly.

Most Panamanians were convinced that the United States did not deal with them fairly and felt a high sense of frustration with Panama’s failure to obtain adjustments in the Canal treaty structure that would favor Panama’s interests. Panama deeply objected to the exercise of sovereign powers by the United States in the Canal Zone and considered the situation an affront to her national dignity. The following documents illustrate Panamanian reaction to this situation.

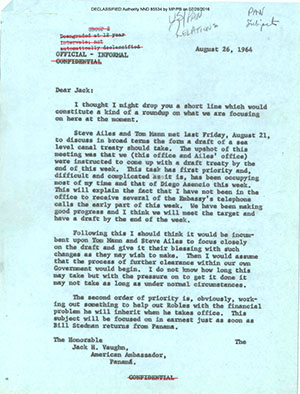

If the United States wanted to improve its relations with Panama, it had to recognize that there were real misunderstandings concerning the treaties, that these misunderstandings needed to be addressed, and that U.S. basic rights concerning the Zone needed to be altered in some way to benefit Panama. Recently declassified records focus on issues such as whether or not the U.S. needed to make concessions, what type of concessions, the extent to which Panama needed to be involved in the Canal’s operation, and Panama's economic link to the Canal Zone. This constant back and forth over what the treaties allowed or didn’t allow created tension between the countries. What follows is a sample of the various documents that focus on this issue.

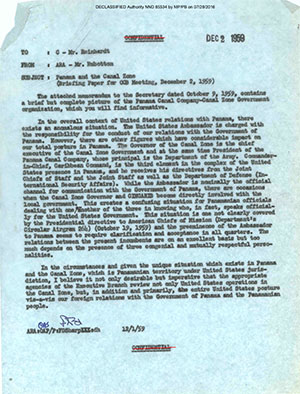

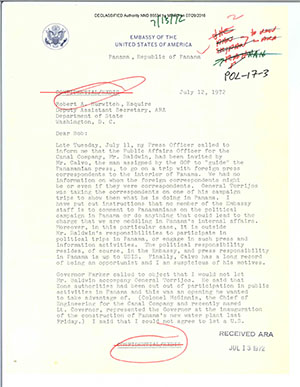

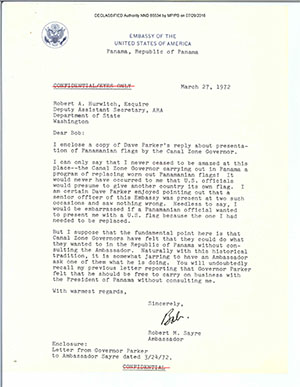

In addition to treaty issues, the day to day Zone operations and living conditions between Panamanians and Zone officials and employees also created tensions. The United States Ambassador was charged with the responsibility for the conduct of relations with Panama. However, there were other U.S. government agencies in the Zone which also affected relations with Panama. This included the Governor of the Zone who was also President of the Panama Canal Company, and the military as represented by the Commander-in-Chief Caribbean Command (CINCARIB) later known as the United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM). These organizations operated independently of each other and did not always consult with each other before determining policy or acting on that policy. The following documents focus on the organizational problems and tensions and how they impacted internal U.S. and Panamanian government relations.

The Canal civilian officials were accused of discriminating against the Panamanian labor force in the Zone while the U.S. citizens that worked on the Zone, known as “Zonians”, were seen as having colonial attitudes when dealing with Panamanians. The presence of U.S. troops and military installations was seen as an “affront” by the local Panamanians to their sovereignty. Whether Panama was or was not treated as a territory or a colony deeply colored the U.S. relations with Panama and affected social and economic interactions between the countries. The following documents highlight this situation.

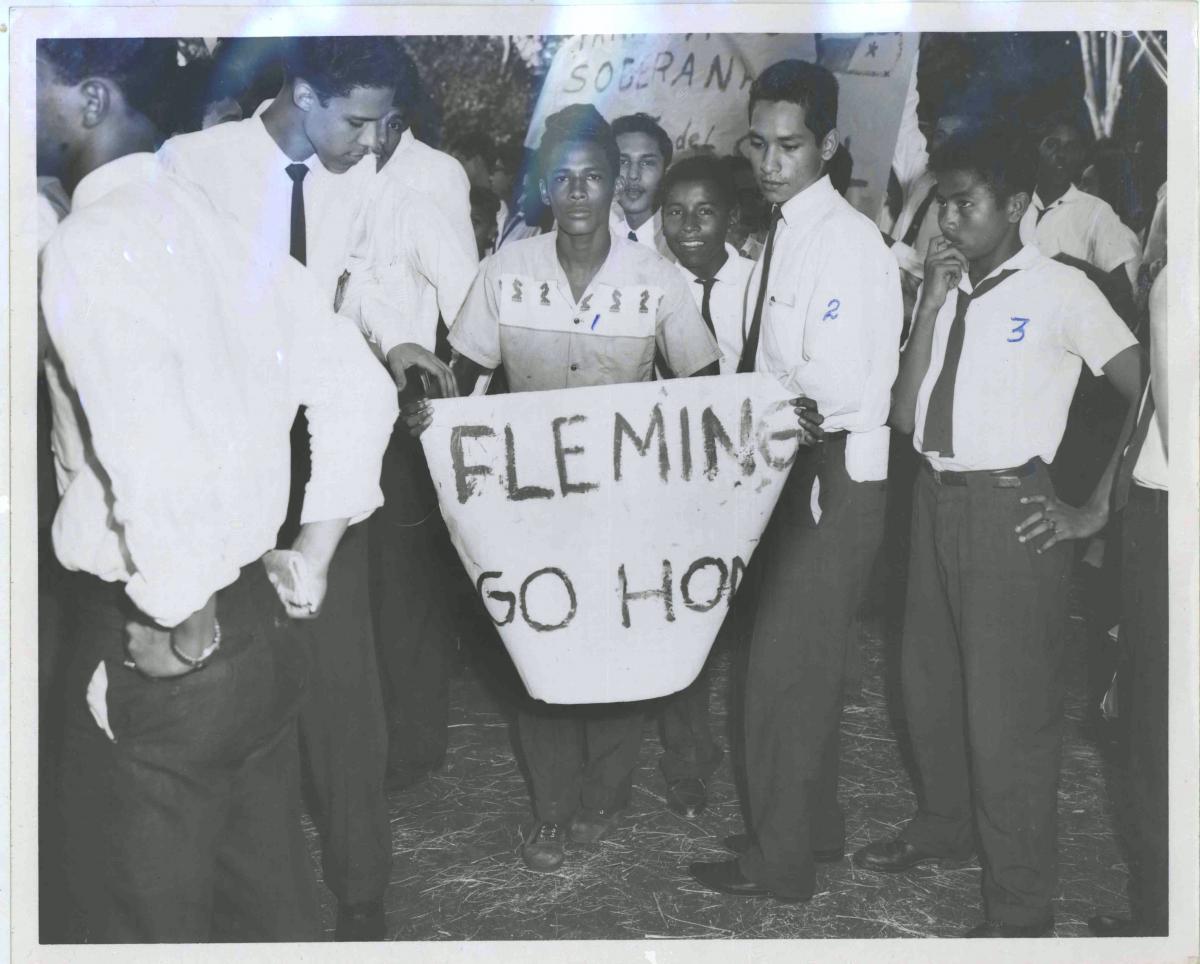

The problems between the U.S. and Panamanians reached fever pitch in 1959 and 1964 with overt riots and demonstrations against U.S. presence on the Isthmus. Although the 1959 demonstrations took place first, they are seldom cited while the 1964 demonstrations are better known and highlighted often to show Panamanian displeasure with the U.S. Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson attempted to address Panamanian violence and demonstrations prior to 1964. In response to the 1959 violence, President Eisenhower issued an announcement of a nine point program to improve relations between the United States and Panama. The program called for such things as pay increases and improved housing for the Panamanian employees, and increased pensions for disabled former employees. However, the program failed to institute changes prior to 1964. The following documents focus on the pre-1964 events that acted as a catalyst to the 1964 riots.

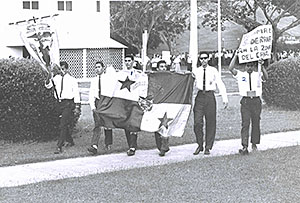

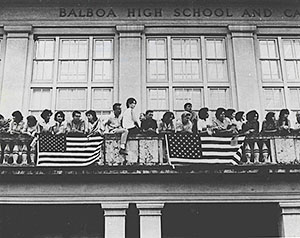

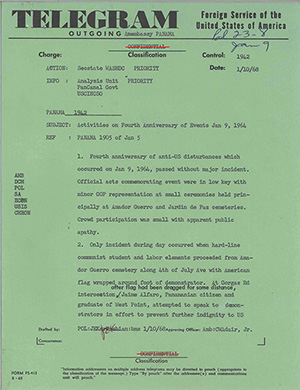

1964 saw more riots and mob violence. The riots revolved around not allowing the Panamanian flag to fly next to the U.S. flag at the Balboa High School. Even though an agreement had been reached sometime in 1962 under President John F. Kennedy to allow the Panamanian flag to be flown alongside the American flag at civilian locations, this order was not carried out. Therefore, on January 9, 1964, with the Panamanian flag still not being flown next to the U.S. flag at Balboa High School, some of the Panamanian students decided to march to the entrance of the Canal Zone to show their displeasure.

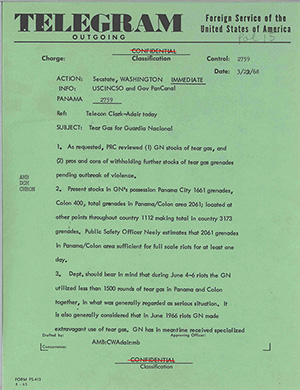

What resulted were three days of riots, destruction of two million dollars’ worth of property, and at least 20 people killed. Panama broke off relations with the U.S. and accused them of aggression and appealed to the Organization of American States and the United Nations. The incident was used as a rallying cry among Panamanians against U.S. authority in the Canal Zone. On December 18, 1964, President Johnson issued a statement announcing that the United States would proceed with plans for a sea level canal and would negotiate with Panama a new treaty to replace the Treaty of 1903. The following documents highlight the considerations entertained by the U.S. government to defuse the rioting.

In the meantime, experts were to determine the need for another canal through 1980 and attempts would be made to give the Panamanians, according to Department of State officials, “enough more or less meaningless concessions over the next few years to keep them from raising too much hell over the issue.” Concessions were always a negotiating point both sides used as leverage against the other as shown in the following documents.

U.S. Foreign Policy, the Canal, and Panamanian Politics

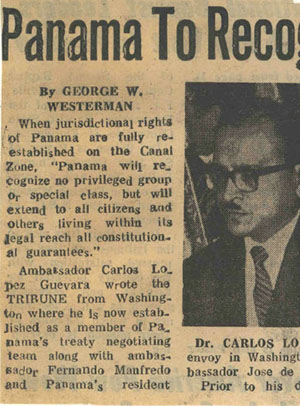

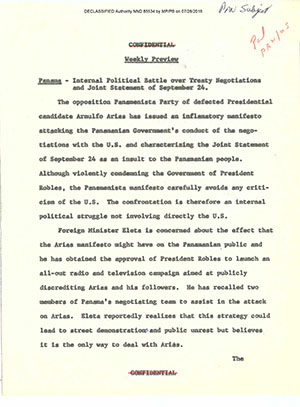

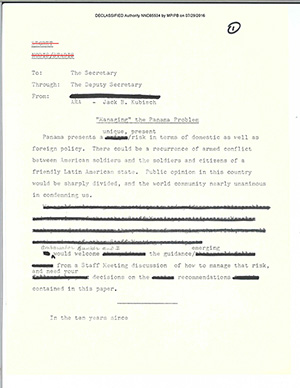

Canal issues and treaty negotiations dominated Panama’s internal politics and relations with the U.S. Both sides saw the canal dispute as an explosive issue that could disrupt the upcoming Treaty negotiations. The treaty negotiations in 1964 became a campaign issue in the Panamanian elections. Various Panamanian political groups used the names of the U.S. and the Canal as reminders to the voters that they have been treated as a territory or colony and not as a sovereign partner as promised in the 1903 treaty.

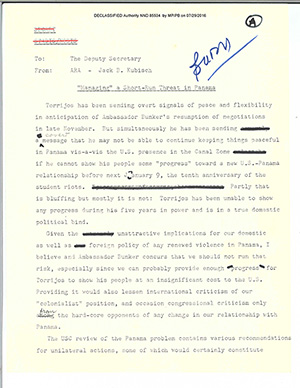

Each group claimed that if elected, under their regime the treaty negotiations would finally secure Panamanian rights as a sovereign nation and increase the country's share in the economic benefits of having the Canal on the Isthmus. Both newspaper articles and radio announcements appeared in support of or against various political views on the U.S. presence on the Isthmus. Panamanian national opinion on the need for change in the United States Panamanian Canal relationship was so fierce that no Panamanian Government, no matter its political makeup, could avoid not taking a strongly nationalistic stand on the treaty question. Therefore, the U.S. felt pressure to be seen as negotiating in good faith. To be seen otherwise could be used as campaign rhetoric to cause the population to take to the streets to riot to show their dissatisfaction with the current treaty situation and U.S. presence in their country.

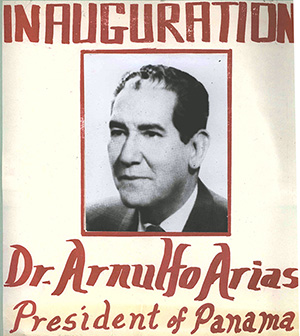

The major candidates for this election were Marco Robles and Arnulfo Arias, and both used their campaigns to remind the U.S. that favorable treaty conditions and economic concessions would calm the Panamanian electorate and ensure successful treaty negotiation to be possible. On May 1, 1964, once voting was completed and the ballots tallied, Robles was narrowly elected. Arias charged that the election was fraudulent but the charges were never proven. The presence of these political tensions is discussed in the following documents.

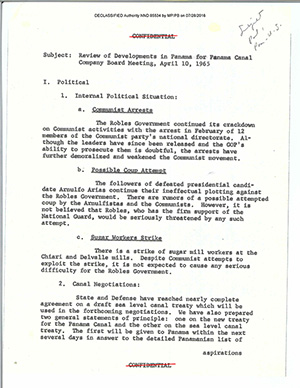

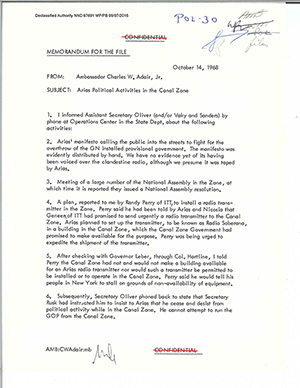

In the months that followed the election, Arias and his Panamenista Party remained opposed to the Robles Government. However, Arias and other opposition groups including the Communists were not able to mount a serious threat to the Robles government to unseat them during an election. However, the Robles government was not in a strong position either, holding only a very thin majority in the National Assembly. Arias and his party used the National Assembly as a platform to criticize the Robles government on issues such as mounting unemployment, fiscal difficulties, alleged corruption, and on its handling of the Canal negotiations. The political players and their agendas are mentioned in the following documents, including highlighting the continued Panamanian internal political tensions.

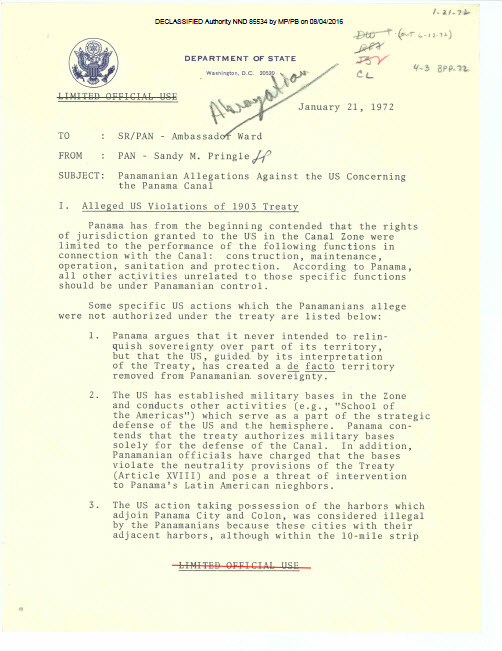

It was not until 1967 that three draft treaties were unveiled to the Panamanian population. The three draft treaties concerned a new Panama Canal treaty, base rights and status of forces agreement, and a treaty for the building of a new sea level canal in Panama. The draft treaty gave Panama its desire for sovereignty over the Zone but it had not deleted the section on the continuation of the presence of U.S. military bases in the Zone, and the U.S. right to deploy troops and armaments anywhere in the republic. The inclusion of language allowing the presence of military bases in the Zone made the treaty unacceptable to Panamanians. Arias supporters and the Communists pointed to this as a failure on the part of Robles to follow through on meeting the aspirations of the Panamanian people. The National Assembly did not ratify the draft treaties. The following documents focus on political developments in Panama.

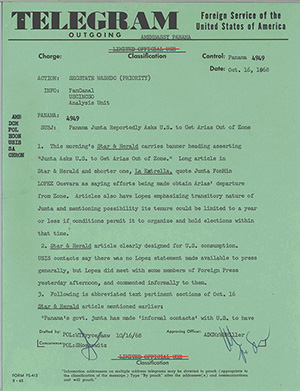

The 1968 elections followed close upon the failure to ratify the draft treaties, and again the focus was on the Canal. This again offered what many observers felt was the opportunity by certain Panamanian politicians to use the Canal question to distract the voters from the real campaign issues of social and economic problems that plagued the nation. Robles would not run again for office but supported the candidacy of David Samudio as president. Thus, Samudio was seen as a political ally of Robes and a political target for former critics of the Robles government. Political groups such as the Communists, and the Ultranationalists would use the unpopular terms negotiated earlier by the Robles’ administration as well as the continued slow moving negotiations against David Samudio, saying that he would do more of the same. The Panamanian electorate was looking for forward progress at this juncture and any movement in the opposite direction was not viewed favorably.

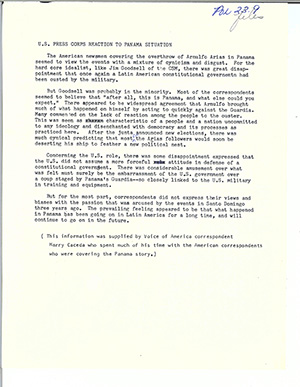

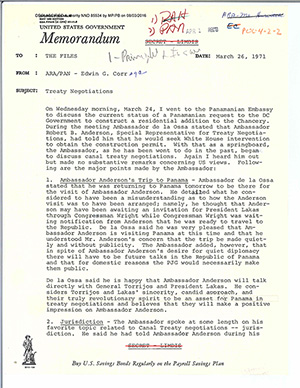

The opposition candidate was again Arnulfo Arias. The election was held on May 12, 1968. Once voting was completed and the ballots tallied, the Election Board declared that Arias had carried the election. Arias took office on October 1, 1968, demanding the immediate return of the Canal Zone to Panamanian jurisdiction and announcing a change in the leadership of the National Guard. President Arias removed the two most senior officers and selected Colonel Bolivar Urrutia to command the Guard. On October 11, 1968 the Guard staged a coup and removed Arias from the presidency. The overthrow of Arias provoked student demonstrations and rioting in some of the slum areas of Panama City. However, the Guard retained control of the country during and after the rioting. Internal political issues in Panama involving the installing of a military junta put the Treaty negotiations in limbo until 1971. The following documents highlight events and issues surrounding the coup and ensuing treaty negotiations.

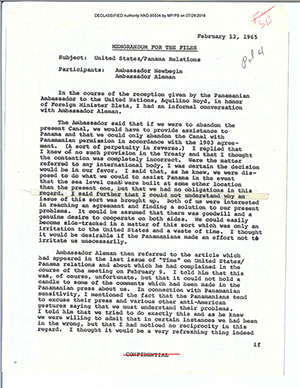

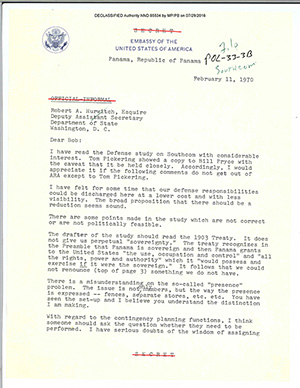

In the years in between treaty negotiations, U.S. officials contemplated various changes in policy that would create a treaty more agreeable to Panama such as the reduction of defense forces, or naming a civilian governor. Also, between negotiations the plan for a sea-level canal was eliminated. In 1965, it was thought that a new canal would be needed soon due to the increase in the size of commercial vessels but the U.S. did not know where to build such a canal, and by the early 70’s the U.S. was unsure that there needed to be one. Thus, the three-treaty package was no longer realistic. Once the “sovereignty” and “perpetuity” issues were resolved, attention would be fixed once again on that part of the treaty negotiations dealing with military bases. These new considerations are analyzed in the following documents.

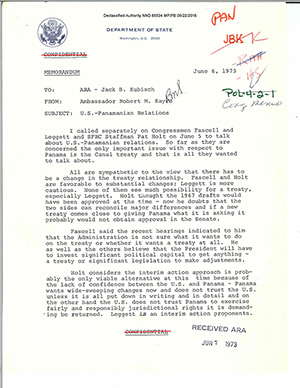

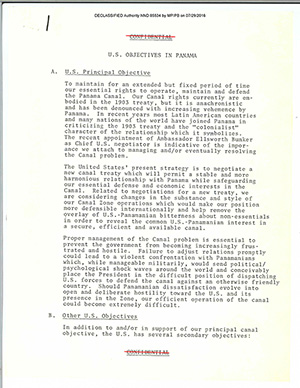

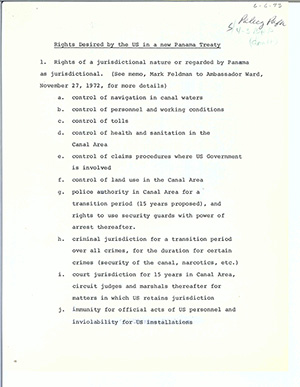

Later in 1971, Panama and the U.S. agreed to resume negotiations and spent six months on what all thought was an acceptable treaty package. However, nothing was done with the negotiated package from December 1971 to December 1972. Negotiations were resumed again in 1973. At this time, General Omar Torrijos, leader of Panama confronted the U.S. with demands for virtual elimination of U.S. presence in the Zone by century’s end. On the U.S. side, conservative opinion hardened and held to the position that the U.S. had to safeguard its defense and economic interests in the Zone. However, the world community pressured the U.S. to be more conciliatory to Panamanian demands for more economic concessions in the form of a sizeable Alliance for International Development (AID) program. Also, the U.S. offered increased promotional trade efforts to keep lines of negotiation open. These new considerations are discussed in the following documents.

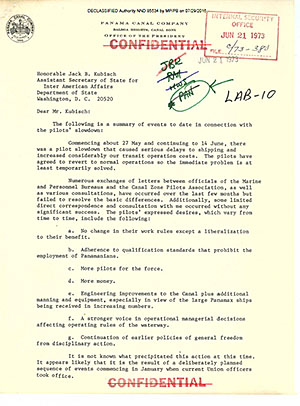

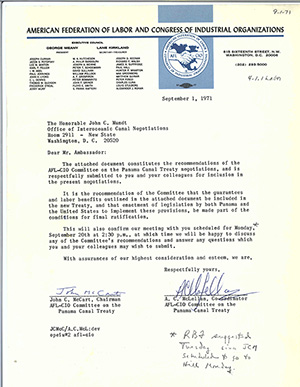

During these years of negotiations, the Panamanians were not the only group interested in the treaty negotiations. The U.S. Congress, the Zonians, and U.S. labor organizations were also putting pressure on the negotiations to get terms more favorable to U.S. employees interests. The American canal workers called for the U. S. government to protect them from losing what many outsiders saw as their “cushy” jobs and work benefits which included such things as paid health insurance, 25% tropical differential, generous vacation time, duty-free shopping and low subsidized rents and utilities. It did not help that the Canal Zone Public Relations operation sent mixed signals to its workers. By praising the virtues of Canal operations, it encouraged the Zone residents to resist change and cherish the status quo instead of embracing the change that Canal officials were leaning toward.

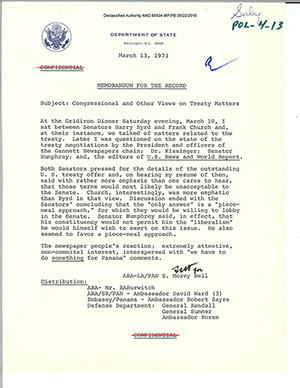

The U.S. House was influenced by an active lobby of U.S. Citizen Canal Zone employees many of whom were second and third generation residents of the Zone and who fought any erosion of their “rights”. The U.S. Senate tended to side with the shippers who wanted low tolls. Department of State officials faced the dubious job of keeping the Panamanians happy while keeping the Congress quiet. The following documents are examples of what many critics of U.S. policy toward Panama saw as the diehard inflexibility that afflicted the Zonians, the United States public in general and the Congress. The following documents focus on the call for Canal status quo to remain and the rejection of Panamanian views.

Military Affairs

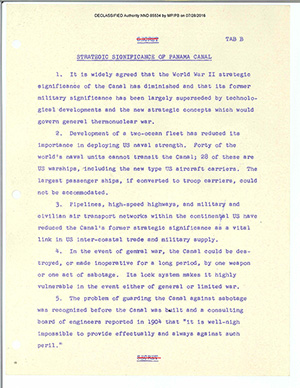

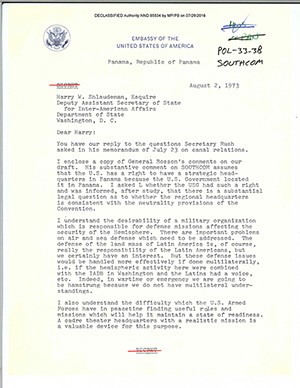

In the 1960’s, military activities in the Zone were under the direction of the United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM). Their primary mission was defending the Canal. In addition, SOUTHCOM served as the nerve center for a wide range of military activities in Latin America, including communications, training Latin American military personnel, overseeing United States military assistance advisory groups, and conducting joint military exercises with Latin American armed forces, as well as conducting a jungle operations training center, and an Inter-American Air Forces Academy. However, the Command’s activities were not welcomed.

One continuing issue related to the treaties was the presence and function of U.S. military bases. United States military forces constituted a large presence on the Isthmus. The military was a potential consumer of goods as well as an employer of a civilian work force of which 70 percent were Panamanian nationals. However, Panamanians continued to question the need for U.S. military bases. To many, the military bases were more closely linked to the control and suppression of civilian populations and not to the defense of the Canal.

The U.S. supported the continued presence of the military on the Isthmus, not only as a defensive stance but also presented their presence as an economic plus for the Panamanian economy. The Panamanians pointed out that they were capable of providing Canal defense themselves and that much of the military activities were questionable and inappropriate under the original treaty agreements (as amended), such as conducting military training exercises, jungle warfare, and environmental testing. As late as 1971, U.S. military officials wanted language in the treaty to safeguard its rights to defend the Canal unilaterally and conduct specific military activities such as creating military schools and military training.

The Panamanians were vehemently against U.S. forces on the Isthmus for several reasons one of which was the military’s support of the Panamanian National Guard. In the 1960’s the U.S. military trained most of the Guard’s officers and NCOs (Non-Commissioned officers) at the School of the Americas in the most up to date ways in controlling unruly crowds. The Guard also was equipped with arms and supplies from the U.S. military.

Many in Panama saw the pre 1968 rule of the Panamanian oligarchy as an obstacle to more citizens raising above the poverty level. The Oligarchy’s use of the Guard during disturbances in 1964 did not endear them to their citizens. Thus U.S. military support of the Government of Panama’s police force (the National Guard) cast them in the role of protectors of the Status Quo. Therefore, any action of the National Guard during demonstrations or other forms of protest would not bring joy to the majority of the Panamanians and the U.S. military image would suffer accordingly.

Another reason the U.S. military was not welcomed on the isthmus was what many locals saw as the large number of bases and facilities. This bolstered the idea that Panama was a territory of the U.S. The following documents highlight the military’s stand in favor of keeping U.S. bases on the Isthmus and the opposition it encountered.

Conclusion

It is hoped that highlighting these records will supplement the ongoing study of this important aspect of U.S. history. As we are able to identify and declassify more records from the custody of the National Archives and Records Administration that deal with this transitional period in both Panama and Canal history, we will be able to supplement this introduction with additional information and continue this important dialogue.