Free at Last

John Boston - An Escape from Slavery, 1862

The institution of slavery in America is older than the republic itself and so is the story of emancipation. Since colonial days, people held as slaves embraced American principles of liberty and equality as their own best hope for freedom and better treatment. Many acted as agents of their own liberation, claiming their freedom in the courts, in the military, and by fleeing to places where slavery did not exist.

By the onset of the Civil War in 1861, there were 3.9 million slaves in the United States. It was clear to them that slavery was at the heart of the national conflict, and with the nation at war, thousands saw an opportunity for freedom and seized it. Tearing themselves from their families, risking their lives, they fled to the Union Army offering themselves as workers, informants, and soldiers. In countless instances during the Civil War, emancipation was achieved one soul at a time, through extraordinary courage and at immeasurable cost.

In the midst of the Civil War, emancipation was pushed to the top of the nation’s agenda as a moral imperative and military necessity. Congress formally proposed the thirteenth amendment outlawing slavery on January 31, 1865; it was ratified on December 6, 1865.

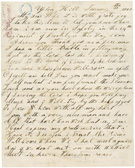

Letter from John Boston, a runaway slave, to his wife, Elizabeth, January 12, 1862

Fleeing slavery in Maryland, John Boston found refuge with a New York regiment in Upton Hill, Virginia, where he wrote this letter to his wife who remained in Owensville, Maryland. At the moment of celebrating his freedom, his highest hope and aspiration was to be reunited with his family.

There is no evidence that Elizabeth Boston ever received this letter. It was intercepted and eventually forwarded to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

National Archives, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s–1917

Excerpt:

“My Dear Wife it is with grate joy I take this time to let you know Whare I am

i am now in Safety in the 14th Regiment of Brooklyn . . . this Day i can Adress you thank god as a free man I had a little truble in giting away But as the lord led the Children of Isrel to the land of Canon So he led me to a land Whare fredom Will rain in spite Of earth and hell Dear you must make your Self content i am free from al the Slavers Lash . . . I am With a very nice man and have All that hart Can Wish But My Dear I Cant express my grate desire that i Have to See you i trust the time Will Come When We Shal meet again And if We dont met on earth We Will Meet in heven Whare Jesas ranes . . .”

—From John Boston’s letter to his wife

.

Envelope for Letter from John Boston, a runaway slave, to his wife, Elizabeth, January 12, 1862

National Archives, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s–1917

.

African American soldiers mustered out at Little Rock, Arkansas, drawing by Alfred R. Waud, published in Harper’s Weekly, May 19, 1866 (Detail)

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC

.

Pvt. Hubbard Pryor of Georgia, before and after his enlistment in the 44th U.S. Colored Infantry, 1864

National Archives, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s–1917

.