Congress, the President, and the War Powers

Summary:

This lesson will explore the implementation of the war-making power from the first declared war under the Constitution—the War of 1812—to the Iraq War. Using primary source documents, students will investigate how the constitutional powers to initiate war have been exercised by the legislative and executive branches of the Federal Government at several key moments in American history. They will also evaluate why and how the balance of authority in initiating war has changed over time. Students will assess and evaluate the current balance of power.

Rationale:

As future voters, students need the tools to participate as citizens in the nation's future decisions on war. This lesson requires students to evaluate previous war making decisions, and apply that historical understanding to consider how such decisions should be made in the future.

Guiding Question:

What is the ideal balance of power between the President and Congress with respect to war?

Materials:

Recommended Grade Levels:

Grades 10-12

Courses:

U.S. History; U.S. Government; Civics

Topics included in this lesson:

Declarations of war, separation of powers, Constitution, Article I, Article II, War of 1812, Mexican War, Civil War, World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War, Iraq War, informational texts, primary sources

Time Required:

120 minutes

Documents:

Representative Abraham Lincoln's "Spot" Resolutions, December 22, 1847; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, RG 233; National Archives, Washington, DC. View in National Archives Catalog

Representative Abraham Lincoln's "Spot" Resolutions, December 22, 1847; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, RG 233; National Archives, Washington, DC. View in National Archives Catalog

President James Buchanan's message to Congress requesting legislation to protect Americans in the Isthmus of Panama, February 18, 1859; Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46; National Archives, Washington, DC. View in National Archives Catalog

President James Buchanan's message to Congress requesting legislation to protect Americans in the Isthmus of Panama, February 18, 1859; Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46; National Archives, Washington, DC. View in National Archives Catalog

"Day of Infamy" message to Congress from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt concerning the Japanese attack on the United States at Pearl Harbor; December 8, 1941; Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46; National Archives, Washington, DC. View in National Archives Catalog

"Day of Infamy" message to Congress from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt concerning the Japanese attack on the United States at Pearl Harbor; December 8, 1941; Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46; National Archives, Washington, DC. View in National Archives Catalog

President Harry S. Truman's statement on Korea, June 27, 1950; Papers of George M. Elsey, Harry S. Truman Presidential Library, Independence, Missouri. View in National Archives Catalog

President Harry S. Truman's statement on Korea, June 27, 1950; Papers of George M. Elsey, Harry S. Truman Presidential Library, Independence, Missouri. View in National Archives Catalog

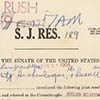

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as introduced, August 5, 1964; Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46; National Archives, Washington, DC. View in National Archives Catalog

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as introduced, August 5, 1964; Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46; National Archives, Washington, DC. View in National Archives Catalog

President George Bush's Statement on Signing the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002, October 16, 2002; George W. Bush Presidential Library, Dallas, Texas.

President George Bush's Statement on Signing the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002, October 16, 2002; George W. Bush Presidential Library, Dallas, Texas.

Learning Activities

1. Introduction and group discussion

Introduce the students to the Guiding Question. Read the clauses on the war powers that the Constitution grants to Congress in Article I, Section 8, and to the President in Article II, Section 2. After reading these clauses, ask the students what sense they get about the Founders' thoughts on the use of war powers. Note to the teacher: Students' answers may include the idea the war-making power should not be in the hands of one person. They might also suggest that Congress is responsible for deciding war or peace, for enabling the nation to fight a war, and for providing funding, while the President is responsible for field command of the military. Also discuss what balance of power between Congress and the President they think the Founders intended to create. Why did they do it that way?

2. War of 1812: The first war under the Constitution

The War of 1812 was the first time constitutional war powers were applied. Share the quotes on Handout 1 with your students, and ask them to describe the authors' views of the war making responsibilities of Congress and the President. How do these views compare with the clauses of the Constitution the students read in the first activity? Assess how closely Congress and the President observed the Founders' vision this first time the United States fought a war under the Constitution.

Note to the teacher: You may want to share with the students some of the views of James Madison, the primary author of the Constitution, and the President at the time that Congress first declared war. Madison observed in his formal communications with Congress what he saw as the proper constitutional roles of the executive and legislature. When making a decision to go to war, Madison believed the President had the prerogative to make suggestions to Congress, and Congress had the prerogative to accept or seek suggestions from the President to arrive at its own decision on the question.

3. Balance of Powers

Project or distribute a copy of Handout 2, the Balance of Powers continuum, which illustrates a balance with Congress and the President at opposite ends. Ask students to consider where to plot a point on the chart to mark their assessment of which branch, the executive or legislative, wielded more influence over the use of war powers in 1812, and by how much.

4. Group document analysis of primary source documents

Divide students into four groups. Assign each group the documents from one of the time periods listed on Handout 3. Some documents have facsimiles and all have transcripts. Distribute Worksheet 1 to help them conduct document analysis. The groups will evaluate each document to assess the viewpoint of the author regarding the use of war powers by the executive or legislative branches.

5. Report from groups

Taking each set of documents in chronological order, direct a spokesperson from each group to share the results of the group discussion. The spokesperson should give the title of each document, summarize its content, and then share the group's assessment of the viewpoint on war powers of the executive and/or legislative branches as expressed by the author. The spokesperson will mark the Balance of Powers continuum to denote the group's understanding of each branch's influence on questions of war at that point in time.

6. Iraq War

Distribute the two Iraq War documents to all students, and conduct a document analysis with the full class in the same manner as they did in small groups. Form a class consensus on where to plot the Iraq War on the Balance of Powers continuum.

7. Reflection

Ask your students to reflect on the changes over time in the exercise of war powers by the two branches of government. Is there a pattern to the change? Why might it have changed? Have the changes been positive or negative? Why? Revisit the Guiding Question: What is the ideal balance of power between the President and Congress with respect to war?

Point out to the students that, as future voters, they may have to decide whether or not to support U.S. military action and will need to understand who exercises which war powers. Possible discussion questions include:

- What are the pros and cons of having Congress or the President in charge of making war? Each option reflects different values:

- consensus-building vs. speed

- democratic process vs. secrecy

- debate vs. unity

- The legislature takes too long deliberating when immediate action may be needed.

- The executive may move too fast before the citizenry are fully supportive of the military effort.

- Open deliberation of war plans by the legislature provides a strategic advantage to the enemy.

- Secret war plans made by the executive undermine the very idea of democracy that the nation is fighting to preserve.

- Debate of different plans in the legislature may ultimately create a strong public consensus.

- Unitary control of war by the executive unites the nation behind one plan.

- What are the roles of the legislature and executive when hostilities exist without a declaration of war? (e.g., Cold War, war on terror)

- Is the Founders’ belief in congressional control of war powers still workable in the 21st century? Should the Constitution be amended? If yes, compose the text of the proposed amendment. If no, explain why not.

- Return to essential question: What is the ideal balance of power between the President and Congress with respect to war? If it is off balance now, how does one fix it?

8. Extension Activity—Taking a Stand

Read one of the statements below, and direct students to physically move to different areas of the room that are marked Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, and Strongly Disagree. After groups form for each opinion, ask the groups to discuss why each person moved to that group and for a spokesperson to explain their point of view to the class.

- "The President is the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and as such should ultimately decide when and where to deploy the United States military."

- "Congress has the constitutional power to declare war and as such should ultimately decide when and where to deploy the United States military."

If you have problems viewing this page, please contact legislative.archives@nara.gov.