Sailors, Soldiers, and Marines of the Spanish-American War

The Legacy of USS Maine

Spring 1998, Vol. 30, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By Rebecca Livingston

This year marks the centennial of the Spanish-American War, which was fought between May and August 1898. For many reasons, this short war was a turning point in the history of the United States. The four-month conflagration marked the transformation of the United States from a developing nation into a global power. At its conclusion, the United States had acquired the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. The war was also the first successful test of the new armored navy.

Interest in the Spanish-American War is therefore increasing, and along with it, a desire on the part of many people to learn more about the 280,564 sailors, marines, and soldiers who served, of whom 2,061 died from various causes. The number of participants was not large compared to the approximately three million men who served in the Civil War or the sixteen million men and women who served in World War II. The smaller numbers are in part due to the short length of the Spanish-American War—it ended before many soldiers had even been transported to the war zone. There was also no draft during this war, as there was for the Civil War and the two subsequent world wars. But for the many Americans whose families came to the United States during the mass immigrations of the 1880s and 1890s, the Spanish-American War records are the first military records they can research.

Anyone who has done family or genealogical research in Civil War records will be pleasantly surprised at the fullness and accuracy of the Spanish-American War records. The records tend to be more descriptive and complete, with more consistency in name spelling, than the records for previous wars. By the turn of the century, enlistees were more likely to know their birth dates and how to spell their names. Record keepers were also more likely to list them correctly. These developments increase the likelihood that modern-day researchers will be able to locate birth dates, addresses of next of kin, medical information, and other information about people who served in the war.

With a few significant exceptions, the process of locating records of Spanish-American War veterans is similar to that for Civil War veterans. The best place to start is with National Archives Microfilm Publication T288, General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934. Pension records were carefully compiled when a veteran applied for benefits on grounds of injury, illness, or disability (later, veterans could also receive benefits based on age) or when the mothers, fathers, widows, and minor children of veterans similarly applied for benefits. Pension records typically include the application forms, proof of marriage, proof of children's births, a summary of military service, and usually death certificates. If you want to check if your great-grandfather served in the Spanish-American War and the only information you have is his name, you may be able to use the pension index to learn his branch of service, rank, and military organization. The pension index includes veterans who served in the regular army, state volunteers who were called into federal service, U.S. volunteers (e.g., Rough Riders), regular U.S. Navy, temporary naval personnel, naval militia, U.S. Coast Signal Service, and U.S. Marine Corps.

Researchers should note that the index to pension files intermingles the names of Civil War and Spanish-American War veterans. It is usually easy to distinguish those who served in the Spanish-American War, however, by the "date of service" (at the top right of the index card) or by the date on which they applied for a pension (at the bottom left of the index card.) When researchers know the branch of service and rank of their veteran, they can search the appropriate army, navy, or Marine Corps records described in this article.

Minorities and Women in the Spanish-American War

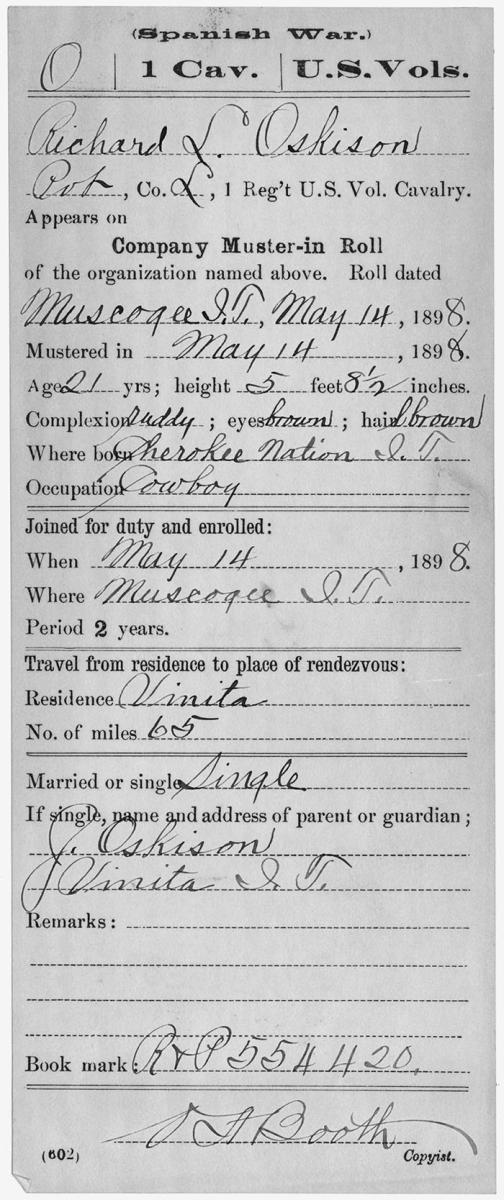

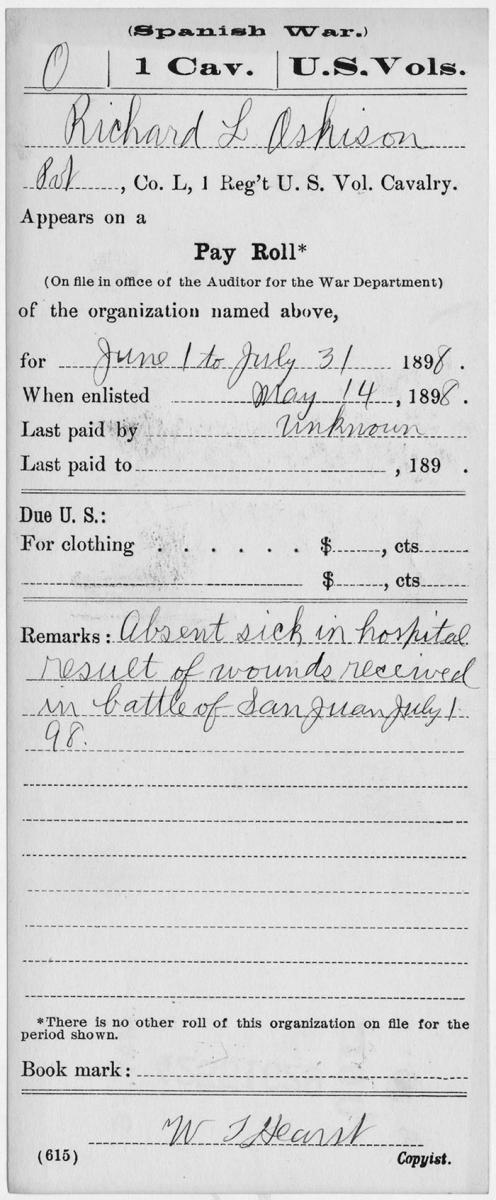

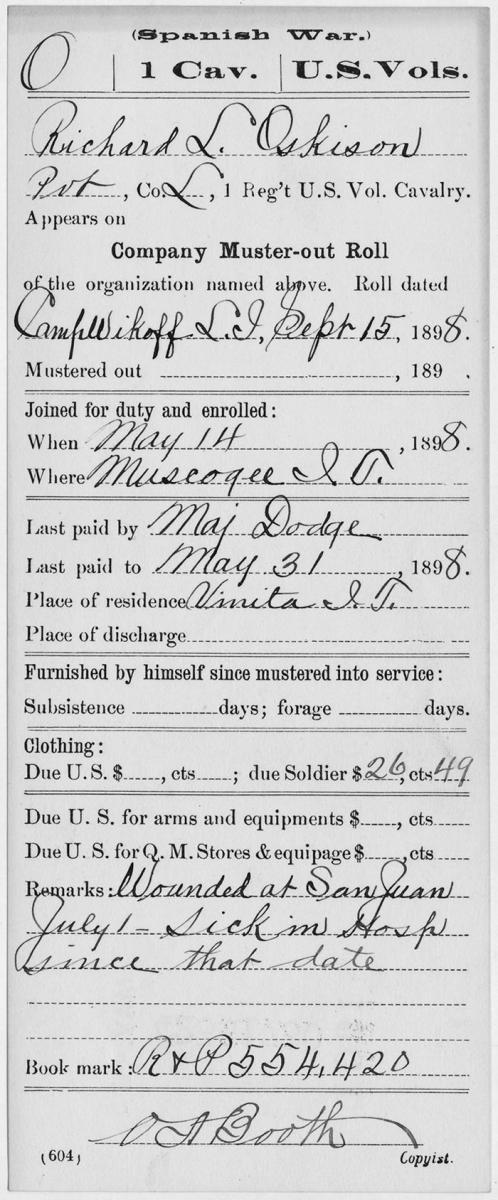

At this time, African Americans served in the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army but not in the U.S. Marine Corps. Women served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, but there are no known records at this time of any women in the U.S. Navy or U.S. Marine Corps. Native Americans fought in the Spanish-American War in the U.S. Volunteers, especially in the First Volunteer Cavalry (Rough Riders) and First Territorial Volunteer Infantry.

On board U.S. Navy ships, African Americans were integrated with sailors of all nationalities. (Many aliens, including Japanese, Chinese, and Filipinos, served on U.S. Navy ships during that era. Some of them enlisted while the ships were in foreign ports.) According to a list of "colored men on board USS Maine, February 15, 1898," 30 African Americans were among the 350 personnel on board at the time of the explosion. Of the 260 men who died, 22 were African American. They typically worked in the engine rooms; as firemen, oilers, and coal passers; or as mess attendants and landsmen. However, there were also five African American petty officers, three seamen (experienced sailors), and one ordinary seaman. Over the ensuing years, a resurgence of racism led the navy to relegate blacks to ratings of mess attendants, including some men who had held much higher ratings during the Spanish-American War.

The names of the African American sailors who served on USS Maine during the Spanish-American War, and the addresses of their next of kin, can be found in the records of the Naval Records Collection, U.S. Navy Subject File, 1775–1910 (hereinafter called the Navy Subject File). Two African American sailors received the Medal of Honor, one for actions at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, another for actions just prior to the official start of the war. Another African American sailor, Fireman William Lambert, was the pitcher for the USS Maine's baseball team. A sketch of him appears in a newspaper clipping from 1898.

African American soldiers served in the U.S. Army's Seventh to Tenth U.S. Volunteer (Colored) Infantries and in the Tenth U.S. Cavalry (whose soldiers were commonly referred to as the "Buffalo Soldiers"). Five soldiers from these regiments were awarded the Medal of Honor. The U.S. Marine Corps did not accept African Americans until World War II.

While there were no known women soldiers, sailors, or marines, the U.S. Army used female nurses both as civilian contract nurses and in the Army Nurse Corps. The Navy Nurse Corps was not established until 1909.

Special Records Relating to the USS Maine Victims and Survivors

For the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, the casualties that resulted from the explosion of the USS Maine (which actually occurred nearly three months before the declaration of war) were far greater than those sustained during the war itself. Only 90 of the 350 men on board the USS Maine at the time of the explosion survived. During the war, there were eighty-five U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps casualties, of which sixteen were men killed in action. A list of the "men lost" and "men saved" for the USS Maine is available in the Navy Subject File. This list of casualties was reprinted in the Annual Reports of the Secretary of the Navy for 1898. Due to the widespread newspaper coverage of the incident and the significance of the event to the outbreak of the war, there are special records that provide information about both the victims and survivors. These special records provide a wealth of family and personal information that one rarely finds among government records of that era.

The National Archives has a collection of the letters and checks sent by two relief societies as well as replies from the family members. One of the relief organizations, known as the "Captain Sigsbee Relief Fund," was funded by Congress. The other, the "Ladies Committee Relief Fund," was privately funded. Both made substantial efforts to locate the widows, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, and even cousins of the lost men. The relief societies helped place offspring of the dead servicemen in orphanages and contributed to the children's care. They also wrote hundreds of letters to post offices and embassies searching for addresses of family members. This correspondence represents a real treasure trove for genealogists. The records show that sailors and marines on the USS Maine had families in all parts of the world: the United States, Canada, Ireland, England, Denmark, Russia, Spain, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Greece, Australia, and Japan.

Many of these letters describe the intense grieving of the families and their desolate poverty, which was aggravated by the loss of pay to their sailor sons and husbands. One mother of twelve children pleads for help because she was too sick to work at anything other than "taking in laundry." Other mothers sent the relief organizations newspaper clippings, prayers, and in one instance, a photograph in tribute to their sons. In some cases, the letters reveal family discord. A sister of one of the USS Maine's victims asked that her father be denied benefits because he would use it only to get drunk. With her letter, she enclosed a newspaper article describing her father's record of arrests. In another case, a widow resentful of money given to her mother-in-law commented, "She was always mean to her son and kicked him out on his own." Another case involved a unmarried woman, Mary Anderson, who had a baby by a victim of the USS Maine. She applied for relief so she could obtain medicine for the baby, who had fallen ill. Because the sailor already had a wife, Miss Anderson was ineligible for his back pay or pension benefits that she might have been entitled to as a common-law wife. Although the relief fund eventually sent her some money, it came too late to save her sick baby.

The correspondence between the relief organizations and victims' families also hints at the sorry state of race relations at the time. Some of the letters suggest that the relief societies investigated the "worthiness" of some of the African American families before providing benefits.

Filed with this correspondence are also letters from the Navy Department to families of the victims. Usually these letters answer questions about the identities of the victims in response to queries. Most mothers or widows received a letter saying, "We regret to inform you that your son was on the list of persons who were lost." One particularly sad case is revealed in a letter from the Navy Department to the brother-in-law of a marine who wrote, "Please send us information about Private John Brown. His wife is expecting a baby any day now, and is very anxious to know if her husband is alive or dead." Mrs. Brown received a letter of condolence from the Navy Department. She delivered a baby girl on March 3, 1898, sixteen days after the explosion that killed her husband.

There were a few happy letters, though, including one that began, "Your son is recovering at the Navy Hospital, Key West." Another stated, "Although your son had been ordered to USS Maine, he was still on board USS Texas at the time of the explosion."

Correspondence of the relief groups, the letters of condolences from the Navy Department, and the resulting "thank you" letters from the families are among the "correspondence relating to Naval personnel lost in the sinking of the Maine," which is arranged alphabetically by name of sailor or marine.

Regarding the survivors of the USS Maine, there are medical records of treatment at naval hospitals and their requests for compensation for personal possessions that went down with the ship. Their claims for lost possessions are located in the Navy Subject File. The records also include a list of addresses for all the survivors as of 1926. Another undated list of survivors indicates that seven men later deserted the U.S. Navy, and another two ended up at the Government Hospital of the Insane in Washington, D.C. Many no doubt experienced great trauma witnessing the drowning, burning, and mutilation of their comrades. Many who survived had serious burns and injuries. Some spent long periods convalescing in naval hospitals, and the relief groups offered money to these hospitalized sailors.

The survivors' claims for lost possessions reveal much about shipboard life at the turn of the century. A Japanese cook claimed to have lost "a Japanese-English dictionary, grammar books, a geography book, a translation of Parry's [sic] history, a sealskin vest, and a gold scarf pin with opal, a gift from his parents when he left Japan and are therefore without price." Other items claimed to have been lost by survivors included a camera, banjo, and dress sword. More routinely, survivors reported losing clothing, bedding, shaving kits, pipes, watches, knives, and Havana cigars. All of the survivors claimed a whisk broom and ditty box. Incidentally, although a large number of the survivors claimed to have lost Cuban cigars, the navy made allowances for only five hundred cigars per claimant. The USS Maine's chaplain, who claimed he had lost nine hundred Havana cigars when the ship sank, was out of luck.

Navy Records

Enlisted men. Personnel files for enlisted sailors who served after 1885 are at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri. Researchers seeking to study these records should use Standard Form 180 and send it to the National Personnel Records Center, Military Records, 9700 Page Avenue, St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 1 Archives Drive, St. Louis, MO 63138. The National Archives in Washington, D.C., does not have an index of these personnel records or compiled or consolidated records of any type for enlisted sailors. However, researchers able to visit the National Archives in person, and willing to search through old fragile volumes, can successfully ferret out the information that is typically included in a personnel file.

The National Archives Building does have annual registers of enlistment, called the "keys to enlistments, 1846–1902," for sailors. These registers are arranged by the year (or partial year), then by the first letter of the sailor's surname, and then by the date of his enlistment. The five volumes for 1898 include records for most of the sailors who enlisted in response to the outbreak of the war or who enlisted for the war's duration. If you are searching for a John Brown, for example, you would need to check all the "B" enlistments for 1898. From these records you can learn the sailor's rating, date of enlistment, place of enlistment, terms of enlistment (e.g., one year), the names of the ships on which he served, and his discharge date. The records do not indicate earlier or subsequent enlistments. Sailors could enlist for terms from one to four years. Boys aged sixteen to seventeen were required to enlist until their twenty-first birthday. Since some sailors who served in the Spanish-American War enlisted before 1898, researchers should also check the keys to enlistment for 1894–1897.

Another source of information at the National Archives is a register of Bureau of Navigation correspondence with enlistees for the years 1896–1902. However, this register is only suitable for the most patient and hardy researchers. It is arranged by the first letter of the enlisted man's name and then by the date of the correspondence.

When you know the names of ships on which a veteran served, you can examine U.S. Navy muster rolls and conduct books. Both are arranged alphabetically by name of ship. The muster rolls are nearly complete for every ship. The conduct books are a much less comprehensive collection. Musters were taken quarterly and cover the preceding three months. Within each muster roll, sailors are listed by the first letter of their last name. For each sailor the rolls show his name, rating, date of his present enlistment, place of enlistment (city or ship), citizenship (native, alien, or naturalized), date received on board the ship, reason for leaving the ship (transfer, death, end of enlistment), and place transferred, discharged, or died. If the rolls show a "continuous service certificate number," it means that the sailor had a previous enlistment. A check mark or "OK" penciled in beside a name indicates that the person was entitled to the Spanish-American War campaign badge, the "Sampson Medal."

In addition to the main set of navy muster rolls, there is a separate, smaller set that combines navy muster rolls with shipping articles. Shipping articles are records of the enlistee's terms of enlistment, and they include his signature, something not found in the main set. Some also provide physical descriptions of the enlistee, which are not in the main set either. These records are unavailable for many ships, however.

Conduct books, which describe the enlistee's conduct and performance during drills, are another excellent source for genealogists. They show the same information as the muster rolls, but conduct books may also include address of next of kin, birth date, birthplace, marital status, years of previous naval service, personal description, punishments, scores on drills and training, and medical condition (good or poor). The names in conduct books may be unarranged or arranged alphabetically, by muster number, or by rating. Some conduct books have name indexes.

Commissioned officers. The service records of regular navy officers who served in the Spanish-American War are available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M1328, Abstracts of Service Records of Naval Officers ("Records of Officers"), 1829–1924. The descriptive pamphlet contains a name index to the abstracts. There are also registers of officers arranged by name of ship or station. Other good sources of information about officers are the proceedings of the promotion examining boards and retirement examining boards, found among records of the Judge Advocate General's Office. Names and dates of service of naval officers are printed in List of Officers of the Navy of the United States and of the Marine Corps from 1775–1900, edited by Edward W. Callahan. Most Spanish-American War–era U.S. Navy logbooks include a list of officers in the first few pages of each volume. For biographical records about chaplains, there are Chaplains Division records, a collection of records used to write a history of the Navy Chaplain Corps. Records of medical officers are located among records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

Acting officers. During the Spanish-American War, many volunteers were given temporary commissions. The National Archives has copies of these acting officers' commissions and discharges or resignations, in addition to order books. A register of temporary officers shows their assignments and "remarks." There are special records for acting engineers, including application papers and order books, and a register of commissioned officers of the Auxiliary Naval Force, 1898.

Warrant officers. Application papers and examination papers are available at the National Archives for the following warrant officers: carpenters, boatswains, gunners, and machinists. Many of them were promoted from the comparable chief petty officer position (chief boatswain's mate, chief machinist mate, etc.) Others were appointed from civilian life because they had related experience in their civilian occupations. The papers include letters of recommendation from civilian employers or commanding officers. Promotion Board proceedings are another excellent source for information about warrant officers.

Navy medical records. The National Archives has medical logbooks kept by ships' surgeons and by surgeons at shore stations. These logs describe medical treatments received by officers and enlisted men and their return to duty or death. There are also registers of patients at U.S. Navy hospitals.

Court records. Additional information about some sailors and marines who served in the Spanish-American War, including both officers and enlisted men, can be found in proceedings of U.S. Navy courts-martial, courts of inquiry, boards of investigations, and boards of inquest. In these proceedings, researchers can learn about men who were in trouble, who were investigated for various reasons, or who died by accident or as a result of foul play.

Marine Corps Records

Enlisted men. Personnel jackets ("case files") for marines who fought in the Spanish-American War can be found in two places. If the marine was discharged before 1906, his personnel jacket is at the National Archives. If the marine continued to serve after 1906, his personnel jacket is at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri. A typical personnel jacket includes enlistment papers, descriptive list, conduct record from each ship or station, and records relating to campaign badges or awards. Occasionally, the personnel jacket will include a letter from a relative relating to pension benefits, cemetery headstone, or general information. These records usually show the address of next of kin, birth date, birthplace, age, personal description, medical condition, and discharge information. The Marine Corps case files are arranged alphabetically by name of marine for enlistments after 1895. Case files for enlistments before 1895 are arranged by enlistment date. There is a card index to Marine Corps enlistments, 1798–1941.

Officers. The National Archives does not have personnel files for Marine Corps officers for the period around the Spanish-American War. Personnel files beginning with 1896 are at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis. However, researchers who can travel to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., can find monthly reports on the duties to which the officers were assigned and summaries of their service among the Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. There are some correspondence files for officers, 1904–1912, with a name index.

Army Records

Volunteers (regiments raised by states called into federal service). Most soldiers called into service for the Spanish-American War served with regiments raised by their state. A consolidated name index to the compiled military service records of these men has been microfilmed as National Archives Microfilm Publication M871, General Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteers Who Served During the War With Spain. Compiled service records are arranged by state, type of regiment (artillery, cavalry, and infantry), and then by number of the regiment. Within each regiment, the jackets for individual soldiers are arranged alphabetically. There are compiled military service records for both officers and enlisted men. A typical record includes cards that extract the monthly muster rolls and other regimental papers about that individual. Usually the cards show whether the soldier was present with his company, absent on detached duty, or sick. In addition, you may find medical treatment cards and certificates of discharge for disability. The compiled military service records for the Spanish-American War usually show the date of enlistment, place of enlistment, birth place and date, personal description, medical information, date and place of discharge, and address of next of kin.

U.S. Volunteers. The U.S. volunteers were special regiments raised for the Spanish-American War. The most famous of these is the First Volunteer Cavalry, the official name of the Rough Riders. There were three volunteer cavalry units, three volunteer engineers, ten volunteer infantry regiments, and a volunteer signal corps. The Seventh to Tenth Volunteer Infantries were composed of African American soldiers. There are compiled military service jackets for the enlisted men and officers, similar to the jackets for the state volunteers. Their names are also indexed on National Archives Microfilm Publication M871.

Regular army--enlisted. Enlistment papers for men who served in the regular army, arranged alphabetically by name of soldier, show the personal description, age, and birthplace of the soldier. With the enlistment papers are assignment and descriptive cards. Registers of enlistments are available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M233, Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914. The registers show the regiments to which the soldier was assigned and his discharge date. More detailed information about his service can be found in muster rolls, which are arranged by type of regiment, by number of regiment, and then by company, troop, or battery.

Regular army—officers. The War Department did not compile personnel files for regular army officers. For most officers, however, there is a consolidated correspondence file that includes their orders, assignments, oaths of office, monthly fitness reports, promotions, and more. An officer's consolidated correspondence file may be found in several different places. Many officers of the Spanish-American War have a consolidated correspondence file among the Adjutant General's Office Document File ("AGO Doc File"), 1890–1917. The index to this file is available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M698, Index to General Correspondence of the Office of the Adjutant General, 1890–1917. Other officers have consolidated correspondence files among the Appointment, Commission, and Personal Branch (ACP) of the Adjutant General's Office. The index to the ACP files are available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M1125, Name and Subject Index to the Letters Received by the Appointment, Commission, and Personal Branch of the Adjutant General's Office, 1871–1894. Many of the most frequently requested ACP files have been reproduced on microfiche; the others are available in the original format. Officers whose service goes back to the Civil War may have a consolidated correspondence file among the Commission Branch (CB) of the Adjutant General's Office. The CB files are reproduced on National Archives Microfilm Publication M1064, Letters Received by the Commission Branch of the Adjutant General's Office, 1863–1870. The descriptive pamphlet includes a list of frequently requested files. A complete card index is also available. For regular army medical officers, there are service cards and personal papers.

Contract nurses and surgeons. During the Spanish-American War, the army hired many civilian nurses and surgeons by contract. Records of the Surgeon General's Office include case files, personal data cards, and correspondence files for contract nurses and doctors, most of which is arranged alphabetically. A researcher should also check the index to the Surgeon General's general correspondence (Doc File), 1889–1917, under the letter "C" for "contract surgeons" and "contract nurses." Under these categories, there are alphabetically arranged index cards by name of contractor. The cards provide the pertinent consolidated document file number. In addition, there are records relating to contract surgeons among the personal papers of medical officers and physicians.

Unless otherwise mentioned, all the records described in this article are available at the National Archives Building in downtown Washington, D.C. Researchers who are unable to visit the National Archives in person may request copies of records through the mail. This request is made on a National Archives Trust Fund Form 80 [see note], National Archives Order for Copies of Veterans Records. To obtain this form, write to the National Archives and Records Administration, Attn: NWDT1, 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20408-0001.

Note: NATF Form 80 was discontinued in November 2000. Use NATF 85 for military pension and bounty land warrant applications, and NATF 86 for military service records for Army veterans discharged before 1912.

See also these related records:

- NARA Records Relating to Service in the Spanish-American War

- Microfilm Relating to Service in the Spanish-American War