The Hours before Dallas

A Recollection by President Kennedy's Fort Worth Advance Man

Summer 2000, Vol. 32, No. 2

By Jeb Byrne

© 2000 by Jeb Byrne

In November of 1963, to seek support for New Frontier policies and with an eye on the 1964 elections, President John F. Kennedy set out on what was planned as a two-day, five-city tour of Texas.

Well before the President departed for Texas, advance men were dispatched from Washington to make on-the-scene preparations. Among them was Jeb Byrne, who had been serving as a political appointee in the General Services Administration since the Kennedy administration began in 1961.

Byrne, a ten-year veteran of wire service journalism who more recently had been press secretary to a Democratic governor of Maine, was assigned to Fort Worth. His mission was to make sure that the President's stay in Fort Worth went off without a hitch.

In an account written for Prologue, the author relates how the President spent his time in Fort Worth. Byrne also details the challenges he faced as the Fort Worth advance man in making logistical arrangements, handling requests for access to the President, and navigating the shoal waters of the then-dominant Texas Democratic party.

Byrne draws his account in part from papers and other materials he kept from his duty in Fort Worth. He has donated those materials to the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, which is opening them on publication of this article.

Kennedy's stay in Fort Worth came off as planned. His work done, Byrne watched as the President took off in Air Force One for the thirteen-minute flight to Love Field in Dallas— and into the realms of history, legend, and speculation.

Here is an advance man's account of JFK's final hours:

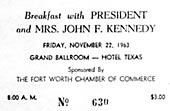

In the early morning of November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy spoke in a light drizzle to a crowd assembled in a downtown Fort Worth parking lot, and then, shortly thereafter, to a dressier audience at a chamber of commerce breakfast in the ballroom of the adjacent Hotel Texas. Although the two events were similar to many other Kennedy public appearances, their evocation carries a special poignancy because they took place in the final hours of his presidency and his life.

As a bit player sent from Washington with responsibility for non-security preparations in Fort Worth, I had stood watchfully on the peripheries of both events. Arrangements for this part of a two-day presidential visit to Texas had been my concern since I arrived in Fort Worth and moved into the hotel ten days earlier.

The story of President Kennedy's Texas trip has been told many times, concentrating inevitably on the tragic denouement in Dallas. This account, however, is simply an advance man's perspective on President Kennedy's stay, and the preparations that preceded it, in neighboring Fort Worth. There, he spent his last night and, on the morning of the day of his assassination, made his last public appearances before his short flight to Love Field in Dallas and the fatal motorcade through that city's streets.

Most of what I relate comes from memory, bolstered by the long-preserved paper detritus that I had swept into a briefcase while vacating a hotel room in a time of turmoil: the President's itinerary, flight manifests, an annotated breakfast program, a letter to chamber of commerce members describing how to obtain tickets to the breakfast, partial lists of the names of people I had given tickets to the breakfast, odd scraps of paper bearing names and telephone numbers or scrawled notes, copies of progress reports on the Fort Worth advance, a map of the city, and yellowed newspaper clippings. This memory-reinforcing residue of paper was supplemented later by photographs that had been taken of the formation of the presidential motorcade in front of the Hotel Texas in the late morning of November 22 and by an unpublished summary of the Fort Worth presidential visit I had written while the events were still fresh in mind. Because what follows is an account rooted in memory, I have eschewed the use of endnotes. Copies of relevant materials have been deposited in the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston.

Involvement in President Kennedy's Texas trip had begun for the assigned Secret Service agents, specialists of the White House Communication Agency, and a handful of advance men—myself among them—on November 12, when we gathered at Andrews Air Force Base on the outskirts of Washington. There we boarded a plane for Texas, where we would prepare the way for President Kennedy's visits on November 21-22 to five cities: San Antonio, Houston, Fort Worth, Dallas, and Austin— in that order. Although all events except a Democratic fundraising dinner in Austin were organized on a nonpartisan basis, the tour was widely viewed as a prelude to the President's impending campaign to win reelection the following year. The political ticket of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson had barely carried Texas in 1960, and success in this state would be important again if they were to be reelected in 1964.

There had been uncertainty in the White House about the efficacy of the tour because of disarray at the top levels of the Texas Democratic Party. The animosity between Senator Ralph W. Yarborough and the state's two other leading Democrats, Governor John B. Connally and Vice President Johnson, was well known. But Kennedy decided to make the trip despite any misgivings he had about factionalism in the Texas Democratic Party and the deep-seated antipathy of some conservative Texans toward his administration.

Our small advance party for Fort Worth was the next to last group to be dropped off in its assigned city when the flight from Washington reached Texas. The others were: William L. Duncan, the lithe and intense twenty-eight-year-old lead Secret Service agent for the Fort Worth visit who was a member of the White House detail; Ned Hall, a second Secret Service agent from the White House detail; army Maj. Jack Rubley, who was operations officer of the White House Communications Agency (WHCA); and army Capt. Bill Harnett, who was junior to Rubley at WHCA. Rubley was along on the trip to give Harnett his "check ride" in performing WHCA's duties on an overnight presidential stay. The Secret Service agents would, of course, provide security for the President. The communication specialists would set up the traveling "electronic White House," which would keep members of the presidential party in quick touch with Washington, the wider world, and each other.

I was to handle other aspects of the advance. Nonsecurity aspects of presidential advancing were much less structured in the early 1960s than in later years. Beginning with President Richard M. Nixon's administration, a permanent office within the White House has had overall responsibility for advancing presidential trips. No such formal unit existed within the White House in 1963. Advance men usually were enlisted on an ad hoc basis for individual trips. I was borrowed for the Fort Worth assignment, willingly enough on my part, from my less exciting regular job in a federal agency.

In Fort Worth, we were met by agent Mike Howard from the Secret Service's Dallas office, who was to work with Duncan and Hall on presidential security. We checked into the Hotel Texas, ate steaks together in the Cattlemen's Restaurant, and exchanged notes on our plans for the next day. Rubley and Harnett would be conferring with their contact at Southwestern Bell Telephone Co. I asked Duncan and Hall to come with me in the morning to meet Raymond E. Buck, president of the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce, which was sponsoring the breakfast that was the central event of the presidential visit. After dinner on the night of our arrival, the agents and I drove around Fort Worth to familiarize ourselves with street patterns.

The next morning, I wondered for a brief moment if Raymond Buck manufactured shovels. There was a row of them along a wall of his spacious, ground floor offices. But these were not fated to gouge dirt more than once. Each of them, painted and bearing a plaque, had been used in a groundbreaking ceremony for a new building. Lawyer, president of insurance companies, and a past Democratic state chairman, Buck was a big man with white hair curling down the back of his neck.

"I'm the last of the long-haired Texas politicians since Tom Connally died," he told us as we sat around a conference table. This was a reference to former Texas Democratic Senator Thomas Connally (no relation to Governor Connally), who had died a few weeks earlier and whose Senate seat, which he had vacated in 1953, was now held by Yarborough.

Buck said that he was a longtime friend of Lyndon Johnson's. We discussed the basic program for the presidential visit. He said he had been waiting for guidance from Washington before making final arrangements for the November 22 breakfast event. The grand ballroom of the Hotel Texas had been reserved, but no invitations or tickets had been issued. The ballroom would hold two thousand persons, including members of the working press who would not be eating. The chamber of commerce planned to send out a letter to its members inviting them to apply for tickets. Buck said that there were about three thousand members of the chamber, and he expected that at least one thousand tickets would be requested, half for members and half for spouses. He added that Governor Connally wanted two hundred to three hundred tickets, Congressman Jim Wright of Fort Worth sought between three hundred and four hundred, and Senator Yarborough was expected to ask for a sizable number. Moreover, organized labor, the Democratic county organization, and a state senator were seeking blocs of tickets, and it had been tentatively arranged to set aside fifty for local federal officials, fifty for county officials, and twenty-five for city officials.

Visualizing the quick disappearance of all the tickets, I made haste to enter a White House claim for at least two hundred. Buck nodded his agreement. The letter to chamber members would say that tickets would be limited and would have to be picked up on a first-come, first-served basis. Members of the chamber were to pay three dollars a ticket. Buck said that he and "several others" would pay for the rest of the tickets. At this point I inquired to what extent the breakfast would be integrated. Buck said he understood that about thirty of those attending on labor tickets would be black.

Although the chamber president had indicated that little had been done about arrangements, a basic program had been developed and a head table proposed, neither of which required radical changes. The breakfast guests were to be served starting at 8 a.m. and would be finished with their meals by the time the Kennedys arrived in the ballroom. The four-piece Jimmy Ravitta orchestra and the Texas Boys' Choir would perform. A long head table would accommodate heads of local governments, officials of the chamber of commerce, and a labor union representative, as well as the political personages from Washington and Austin. Spouses also would be seated at the head table. Tactfully, Buck had not attempted to name the person who would introduce the President.

"You do it," I told him.

After the meeting with Buck, the Secret Service agents began to make their contacts. I knew they were busy, but it was not until years later that I read agent Duncan's "Final Survey Report" in the National Archives and found that 508 persons had participated in security at the Fort Worth stop (Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, Record Group 233, Washington, D.C.). The Fort Worth Police Department assigned 300 officers, the Carswell Air Force Base Police 80, the Tarrant County Sheriff's Department 60, and the Texas State Police 5. The Secret Service, including agents who traveled with the President and those in the advance party, had 32 on hand. The Fort Worth Fire Department and the River Oaks Police Department also contributed personnel.

Before leaving Washington, I had received the name of a Fort Worth attorney, David O. Belew, Jr., who was to be my local contact with Governor Connally. After leaving Raymond Buck's office, I went to see Belew at his office. He told me that his wife, Marjorie, was a Democratic state committeewoman and that both of them were being badgered by people seeking more information about the President's activities while in Fort Worth. He mentioned that many party regulars were indignant because of the visit's format, which they said seemed designed to keep the President away from rank-and-file Democrats. The Belews invited me to their home that night to meet with them and other interested parties whom they would assemble to discuss the President's visit.

The "others" at the Belew home, in addition to the pajama-clad Belew children who ducked in and out of the living room, were Garrett Morris, a Democratic state committeeman who was also introduced to me as a manager of Governor Connally's last campaign; Tarrant County Democratic Chairman William Potts; union representatives Garland Ham of the United Auto Workers and John Heath of the International Association of Machinists; and public relations practitioner Bill Haworth. The group was unanimous in pressing for increased public exposure of the President while in Fort Worth. Proposals were made that in addition to his chamber of commerce address, the President speak to a public gathering either in the parking lot next to the Hotel Texas, or four blocks from the hotel at Burnett Park (where he had spoken as a candidate in 1960), or at Carswell Air Force Base following the breakfast and before boarding Air Force One for Dallas. A fourth suggestion was for an extended motorcade "up and down the main streets."

I was a good listener. And in the following days, it became clear that the gathering at the Belews' home had assessed accurately the widespread dissatisfaction among Democrats at the format of the presidential visit. As my name and mission became more widely known, the telephone in my hotel room rang with complaints. Labor leaders particularly were incensed by the Chamber of Commerce's sponsorship of the breakfast. I discussed the problem with Buck, and he assured me that he had no objection to a separate, public appearance of the President as long as it did not interfere with the nonpartisanship of the breakfast to which he had been committed before I came to town. I immediately passed along to Washington the suggestions that I had received, my own observations, and a recommendation that the President's schedule be revised to include a public appearance outside the hotel at which he would speak at least briefly.

In the next few days I began to receive overt reminders from Austin, the state capital, that the conflict between Governor Connally and Senator Yarborough had not appreciably diminished and was not being put aside for the presidential visit. First, it was a message that the governor wanted this order for the motorcade in Fort Worth:

President's car

Vice President's car

Governor's car

Press cars

Senator Yarborough's car

Then there was a request from Austin that congressmen and senators be seated on the breakfast dais at a lower level than the President, vice president and governor. Connally aide Scott Sayers came to Fort Worth and asked me how these requests were faring. I told him that normal political protocol would be followed in Fort Worth. There were no repercussions-at least that I knew about. I had cleared my response with Washington before making it.

About this time, Bill Turner, exalted ruler of Fort Worth Lodge 124 of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, appeared on the scene representing Senator Yarborough. Turner said the senator had instructed him to see that protocol was "strictly followed" on the Fort Worth leg of the trip. "If that means equal treatment," I told him, "the senator will get it." Later, as the dates approached for the presidential visit, Turner came to the hotel and showed me a telegram he had received after reporting to the senator's Washington office on the Fort Worth arrangements. Dated November 19, it read:

Seating, cars, head tables perfectly satisfactory.

Please do not object or complain, it is 100% perfect.

As to stopping at Elks lodge, will see what can be done.

Ralph Yarborough

U.S.S.

The reference to the Elks lodge was an example of the many kinds of requests advance men receive for special appearances or actions by a President in a locality where preparations are being made for a presidential visit. This time, Yarborough's comment was in response to Turner's request that the President visit Turner's fraternal lodge and present it with an American flag. Turner pressed for such a presentation up to the time of the President's visit, but his request could not be accommodated.

The tempo of the final days before the President's arrival accelerated. I began to be in regular telephone contact with Bill Moyers, then-deputy director of the Peace Corps, who had been sent from Washington to Austin as an on-the-scene coordinator for the trip. His mission, I gathered, was to try to reduce discord in the planning process.

I also had become, perforce, a ticket distribution agency. Twelve hundred tickets ultimately had been set aside for chamber of commerce members. The news that Jacqueline Kennedy would accompany the President on the trip had stimulated ticket sales to chamber members and their spouses. Buck kept control of the rest of the tickets. With his cooperation— we got along amiably— I allocated and distributed 550 tickets to various groups and persons outside the chamber's circle, requiring lists of names of those who were to receive the tickets.

While meeting with a labor delegation in my room at the Hotel Texas, I expressed concern about the extent of black attendance at the breakfast. One of the union leaders present told me that despite what I might have heard about the attendance of black persons "there will be damn few unless somebody does something." I asked if anyone knew the number of black people living in Tarrant County. When the figure seventy thousand was offered, I asked for the name of a leader in the black community. The name of Dr. Marion Brooks was suggested. As the labor delegation was going out the door, I was on the telephone with Dr. Brooks and with his assistance placed forty tickets directly with black people— in addition to those who might be included through labor and other connections.

With Latinos, I nearly struck out. The day before the breakfast, the county sheriff telephoned and said that a young man on his staff by the name of Jake Cardenas headed a local unit of the Political Organization of Spanish-Speaking People and was hurt that no one had made a move to involve his group in the breakfast event. I immediately talked to Cardenas and apologized.

"I didn't think of it," I said.

He was polite, but his voice was numb. "Nobody does."

I felt like kicking myself all the way back to Maine, where I had abandoned wire service journalism for politics and government. Although the ticket barrel was at rock bottom, I succeeded in retrieving ten tickets, which he picked up.*

While I was engaged with my set of problems, Duncan, Hall, and Howard went about their business of providing for the safety of the President while he was in Fort Worth. They met with law enforcement agencies that would be involved in the visit, checked the backgrounds of hotel employees and others who would be in close contact with the presidential party, "ran out" and timed motorcade routes and alternatives made arrangements for tight security on the President's quarters in the hotel, and went through the numerous other rituals peculiar to their calling. At night, we met to compare notes.

I also took the time to walk around downtown Fort Worth and get the feel of the city. On one walk, enticed by a sale, I entered a hat store and came out with a Stetson. I tried to appear accustomed to wearing this Western headgear but probably fooled no one. On my rambles, I dropped in twice to The Cellar, a below-the-street place near the hotel, where strange drinks without alcohol were served to the heavy thrum of drums and guitars. The preferred dress style was 1960s Beatnik. The din did not encourage lengthy stays by visitors with unconditioned ears.

The Secret Service agents and I went out to Carswell Air Force Base for a meeting with the commanding officer, Brig. Gen. Howard W. Moore. He contended that because Carswell was a Strategic Air Command base, the public would not be able to enter to observe the President's arrival and departure. I argued that an exception should be made, that it was a highly unusual occasion, and that the people of the Fort Worth area should have the opportunity to see their President come and go. Eventually, Carswell was opened to the public for the visit; no doubt weightier voices than mine were responsible for the reversal of the original, negative decision that I had reported to Washington.

Was it inexperience as an advance man—this was my first presidential advance—or a sense that the Fort Worth arrangements were more accommodating to business interests than to the working man that led me to acquiesce so quickly in one demand by the local labor leadership?

Probably both.

I had made provision for O. C. Yancey, Jr., president of the Tarrant County AFL-CIO, and his wife to represent labor on the reception and departure committees at the airport as well as at the head table for the breakfast. Suddenly, at a meeting in my hotel room, the labor leadership threatened to boycott the breakfast unless other Tarrant County union officials and their wives had the opportunity to meet the Kennedys. Although it was unlikely that the threat would be carried out, I gave in. An elongated reception committee greeted the presidential party on the night of November 21 and, as a departure committee, said farewell in the late morning of November 22. In the serpentine line, as I recall, were Raymond Buck and several other chamber of commerce officials, the Democratic state committeeman and committeewoman, General Moore, the mayor of Fort Worth, the Tarrant County administrative judge, the enlarged delegation from the county's AFL-CIO, and spouses of many of the members of this committee that welcomed and bid farewell to the Kennedys at Carswell.

The prudent presidential advance man tries to avoid getting his name in news reports. Announcements of arrangements are best left to the White House, members of Congress, and local leaders. But sometimes it is unavoidable. For instance, following the session with labor leaders that had ended with me on the telephone to Dr. Brooks, the Fort Worth Star Telegram ran a front-page story headlined "Negroes Invited to Breakfast for JFK" in its November 20 edition. An unnamed "organized labor spokesman" was credited with prodding "one of the White House aides at the Hotel Texas" into issuing invitations to black people. Reporters, of course, sought out the "aides" who were doing such things. Identified, I was contacted by reporters seeking the latest information about the coming presidential visit. On the subject of invitations to blacks to attend the breakfast, I was quoted in the November 21 Star Telegram as affirming my role but pointing out as well that "Mr. Buck was interested in getting an across-the-board turnout of Fort Worth at the breakfast."

Representative Jim Wright, the future Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives who was Fort Worth's congressman, moved into the hotel a few rooms down the hall from mine. He was constantly on the telephone, although we found time now and then to talk about arrangements. The young and personable Wright worked diligently for White House approval of a public appearance by the President in addition to the breakfast speech. I suspect that the acceptance by the White House of a revision in the President's schedule to permit a short talk to the public in the parking lot in front of the hotel owed much to the congressman's advocacy. Moreover, as Wright notes his 1996 book Balance of Power (p. 104), he and Governor Connally had to work hard to convince oilman William A. Moncrief, who owned the city block that included the parking lot, to allow the area to be used for the President's public appearance. Wright says that although the first reaction of Moncrief, no Kennedy supporter, was to decline the request, he "finally relented."

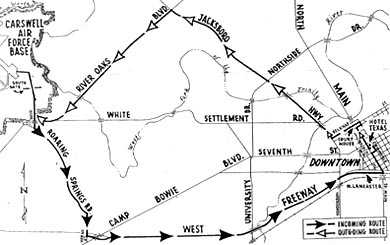

Overall schedules of the Texas trip were appearing in the newspapers for the last few days before the visit. On November 19 the Fort Worth newspapers published a map of the routes the President's motorcade would take, coming and going, between Carswell Air Force Base and the Hotel Texas. I worked with local organizations to encourage crowd turnout. High school bands were asked to play along the presidential route. Local art lovers furnished the Kennedy suite in the hotel with original paintings and sculptures. Raymond Buck obtained through me the hat and shoe sizes of President Kennedy so that a Texas hat and boots could be presented to him. I was aware of the President's aversion to hats, gift or otherwise, but let Raymond Buck convince me that such a presentation was a Texas custom and would do no harm.

After all, the President didn't have to wear the gifts.*

I am indebted to Mike Howard, a retired Secret Service agent who lives in McKinney, Texas, for sharing with me details of some of the security measures taken for President Kennedy's visit to Fort Worth. Howard, from the service's Dallas office, notes that agent Duncan had assigned him as "law enforcement liaison." He visited Fort Worth Police Chief Cato Hightower to advise him of "what was about to fall upon him." Howard sought the chief's help in viewing records of persons in the area who might be threats to the presidential party. He says that thirty people were detained or placed under surveillance. The agent then called on Tarrant County Sheriff Lon Evans to contact all law enforcement agencies in the county to tell them "We needed every body that wore a badge to work November 21 and 22." The call was answered. Even firemen turned out, many of them assigned to posts in the hotel's exits and stairwells.

Howard says that every floor and window in a tall building facing the parking lot where the President was to speak on Friday morning was thoroughly checked. Occupants were asked to keep their windows closed on November 21 - 22, but on Thursday afternoon a policeman spotted an open window on an upper floor. Howard says that two teenage boys in a law office were using a scope to get a closer look at preparations in the parking lot. The problem was that the scope was mounted on a hunting rifle belonging to the father of one of the boys, an attorney in the office. The rifle, taken from an office gun case, was not loaded. It was determined that innocent curiosity had compelled the boys to take a magnified look at the parking lot activity through the scope. The father was notified and the weaponry in the office was safely locked up. Howard also remembers that in another of his Secret Service capacities, protecting the nation's currency, he had to shut down the business of an entrepreneur who, from a table in the hotel lobby, was selling one-dollar bills with a picture of President and Mrs. Kennedy pasted over George Washington's image.

As time went on, two more telephones were installed in my hotel room. The constant ringing of three telephones made the place resound like the inside of a campanile, so I called for assistance. Ross Wilder, on the staff of the Dallas office of the General Services Administration, the agency for which I then was a political appointee in Washington, came over to Fort Worth on November 21 and again on November 22 to help me answer the calls.

On November 21, Thursday, the two of us ate a late dinner and drove to Carswell, where Air Force One was to land shortly after 11 p.m. Streams of cars were entering the gates. As arrival time approached, I lined up the welcoming committee in a hangar and led the long column outside to the light-splashed apron. The blue and white Boeing 707 landed and taxied. The waiting crowd cheered wildly as the pilot of the aircraft, which was marked with the American flag and the presidential seal, cut the plane's engines. The presidential party came down the steps and went through the receiving line. Marjorie Belew handed Mrs. Kennedy a dewy armful of three dozen roses. The President and Mrs. Kennedy moved toward the fences. Cheers rose to a roar. Hands reached for theirs. There were laughter and shouts and a crescendo of cheers as they walked the fences, then entered their car. The motorcade began to move. Wilder and I got into our car and headed for the Hotel Texas.

Downtown Fort Worth was alive with lights and people. After the Kennedys had arrived and had gone to their suite, and the crowd in the hotel lobby had begun to clear, I went up to the President's floor to report to Kenneth P. O'Donnell, the President's appointments secretary and final arbiter of advance arrangements. O'Donnell was standing in a doorway, laughing at the antics of another presidential aide, the ebullient David Powers, who was clowning inside their suite. O'Donnell looked at me.

"Why," he asked, "did the congressmen have to wait at the desk in the lobby instead of being escorted to their rooms when the motorcade got here?"

I told him it was a detail that had not occurred to me. I must have looked abashed because he followed up his abrupt greeting with "Well, it's okay. Everything's fine."

We talked about the morning program, and then I went downstairs to my room. It was after midnight. Passing a mirror, I noticed that I was still wearing the new Stetson that I had donned to go to the airport. I had a belated feeling that this hat was not the proper headgear for a Kennedy advance man to wear when talking shop with Kenny O'Donnell of Massachusetts, a man known for his political toughness as well as his devotion to JFK, on a trip beset by a Texas-sized political problem that clearly was interfering with the main purpose.

Despite O'Donnell's remark about the delay in getting the congressmen to their rooms, I was encouraged by the outcome of the visit thus far. The airport crowd had been large and enthusiastic, streets had been lined despite the late hour, the breach between Connally/Johnson and Yarborough had not been in evidence, and the presidential party was safely in the hotel. I was tired, though, and anxious about the morning events to come. I went to bed, declining an invitation to visit the Fort Worth Press Club, which was staying open late for the benefit of visiting journalists. Just as well. Among those who did go to the press club were some off-duty members of the Secret Service who had just arrived from Washington. A few also visited The Cellar, the aforementioned nightspot. After the Dallas catastrophe, they were pilloried by Drew Pearson, one of the most influential syndicated columnists of the day, for drinking and keeping late hours on a presidential trip. However, there was no evidence at all of extensive drinking by agents of the Secret Service. As one agent told me, they were much more interested in getting a bite to eat than a drink. Meals for Secret Service agents on presidential trips could be erratic.

A misting rain was falling in the morning when I went out to the parking lot to check on arrangements for the President's public appearance. On the roofs of nearby buildings, policemen in slickers were outlined against the gray sky. Despite the rain, the crowd continued to swell. The waiting spectators, many of them men in work clothes, quietly watched the technicians adjusting the public address system on the flatbed truck that would serve as the President's platform.

At 8:45 a.m., President Kennedy, Congressman Wright at his side, strode out of the hotel, neither of them wearing raincoats. Flanking them were Vice President Johnson and Senator Yarborough, with Governor Connally a few steps behind, all three wearing raincoats against the drizzle. Mrs. Kennedy had remained behind in the Kennedys' suite.

"There are no faint hearts in Fort Worth," President Kennedy began when he mounted the platform, "and I appreciate your being here this morning. Mrs. Kennedy is organizing herself. It takes longer, but, of course, she looks better than we do when she does it. . . . We appreciate your welcome."

He went on to speak about the country's defense and the part that Fort Worth, home of such major defense contractors as General Dynamics and Bell Helicopter, played in protecting national security. He touched on the nation's space effort.

The President's delivery was warm and direct. Americans, he said, must be willing to bear the burdens of world leadership. "I know one place where they are," he told his wet audience. "Here in this rain, in Fort Worth, in the United States. We are going forward."

There was prolonged applause from the eight thousand or so people in the parking lot. The President reentered the hotel and, after stopping for some conversations along the way, proceeded to the grand ballroom. As prearranged, the breakfasters were on their coffee when the President walked through the kitchen and down the aisle to the head table to vigorous applause. I watched from the kitchen doorway.

At one point the President beckoned Agent Duncan to the head table and told him to ask Mrs. Kennedy to come down to the ballroom. He also told Duncan to ask the orchestra to play "The Eyes of Texas Are Upon You" when she arrived in the ballroom. Agents Mike Howard and Clint Hill escorted Mrs. Kennedy down from the Kennedys' suite. Lovely in a pink suit, which later would become one of the symbols of the day, she came into the kitchen as Raymond Buck was introducing those at the head table. She waited. Then, with a grand gesture, Buck swung the attention of the audience to the kitchen entrance. Mrs. Kennedy stepped into the room to a tumultuous welcome and joined her husband as the orchestra complied with the President's musical request.

Buck presented the Texas hat and boots to the President. Kennedy thanked him and, to no one's surprise, did not put on the hat—nor, of course, the boots. He began his address lightly, referring to the frequent rising for applause during the introductions.

"I know why everyone in Texas. Fort Worth, is so thin, having gotten up and down about nine times. This is what you do every morning . . ."

He paid tribute to his wife: "Two years ago, I introduced myself in Paris by saying that I was the man who had accompanied Mrs. Kennedy to Paris. I am getting somewhat of the same sensation as I travel around Texas. Nobody wonders what Lyndon and I wear."

The President's prepared remarks were directed at the country's defense posture. The parking lot talk had been a foretaste of what was to come. He enlarged Fort Worth's contribution to air defense: World War II bombers, combat helicopters, and the new TFX planes. It was a speech written for the Texas Chamber of Commerce, and it was enthusiastically received. The President came up the aisle with his wife. Their young and vibrant faces flashed smiles. Hands reached out to the President and he grasped them. The Kennedys went back into the security-cleared kitchen and through a rear door to the elevators.

As the crowd moved toward the exits, craggy Congressman Albert Thomas of Houston, whose big day had been Thursday in his home city, shook my hand.

"Wonderful," he said. "Congratulations on what you fellows did here."

I felt a glow of architectonic achievement. But Congressman Thomas had something in his other hand. He handed me a hatcheck and a quarter and asked if I would mind going through the crowd to get his hat on the other side of the ballroom and meet him in the front of the hotel where the motorcade cars were drawn up. He had missed his assigned transportation once earlier in the trip and was determined not to do so again. A trifle deflated, I went after his hat. He need not have worried. The motorcade would not leave for nearly an hour.

When the Kennedys had returned to their suite shortly after 10 a.m., a rare occurrence for usually tightly scheduled presidential trips ensued: Time off. It wouldn't do for the presidential party to arrive in Dallas too early. During this hiatus, according to later accounts, President Kennedy telephoned former Vice President John Nance Garner at his home in Uvalde, Texas, to wish him a happy ninety-fifth birthday. Garner had served with President Franklin D. Roosevelt during FDR's first two terms. The Kennedys also spent time looking at the art exhibit that had been mounted in their suite especially for their visit but which they had overlooked during their midnight arrival in the hotel. The exhibit included, among other original works, a Van Gogh, a Monet, and a Picasso. The presidential couple telephoned one of the exhibit's organizers, Mrs. Ruth Carter Johnson, whose name they found on a special exhibit catalog in the suite. They thanked her and her associates for their thoughtfulness.

During this waiting period, the President's attention apparently was directed by aides to a nasty advertisement in the day's Dallas Morning News. The ad, paid for by right-wing extremists, accused the President of disloyalty to the country through softness on communism. According to William Manchester's detailed chronicle of the Texas trip in his Death of a President (1967, p. 121), Kennedy mused out loud at this point about how easy it would be to assassinate a traveling President. This was followed by a quick visit to the suite by Vice President Johnson to introduce his sister and her husband to the President. Then, before the Kennedys departed for the motorcade, the President is said to have reiterated on the telephone to aide Lawrence F. O'Brien the importance of getting Senator Yarborough to ride in the same car with the Vice President.

The refusal of Senator Yarborough to ride with the Vice President earlier in the trip, except in the motorcade from Carswell Air Force Base to the Hotel Texas under the cover of darkness, had focused press attention on the rift in the Texas Democratic Party, with Yarborough on one side and Vice President Johnson and Governor Connally on the other. The liberal Yarborough and the conservative Connally had little use for each other. The friction between Yarborough and Johnson appears to have been more complicated, perhaps caused by a clash over the exercise of prerogatives of two leading politicians of the same party in the same state and by Yarborough's perception that Johnson was too closely allied with Connally. But I leave that analysis to the students of Texas politics of the 1960s.

My principal concern after the chamber of commerce breakfast on November 22 was the loading of the motorcade. I was hoping that the process would go smoothly but was apprehensive that it would not. I had not been privy, of course, to the activities in the presidential suite after the breakfast, including the President's final, peremptory telephone order to O'Brien to seat Yarborough and Johnson in the same car. But it was obvious that this maneuver had high priority to discourage negative stories on the political feuding, which was dominating news coverage of the trip. So, after the breakfast event, the recovery mission for Congressman Thomas's hat, and conversations with Secret Service agents and lingering breakfast guests, I went out to the front of the hotel, where the cars for the motorcade were placed.

"Welcome Mr. President" read the lettering on a side of the marquee of the hotel. Two open convertibles, one for the President and the other for the Vice President, were parked at the curb; other vehicles lined up behind them. I stood to one side, arms folded, smoking, waiting. Governor Connally and his wife emerged from the hotel. David and Marjorie Belew were on the sidewalk, and David introduced me to the governor.

"I've heard about your work here in Fort Worth," Connally said. "You did a good job, I understand." There was no mention of the two unfulfilled requests from Austin. I thanked him.

Soon O'Brien and Yarborough came out of the hotel. O'Brien stood nervously by the Vice President's car. Yarborough, with him for a time, wandered away, then returned and entered the car. However, he perched on the back of the rear seat on the driver's side, and his occupancy seemed tentative. At this point O'Brien beckoned to me and asked me to seat the Vice President in the car when he came out of the hotel, adding "You can do it easier than I can." He muttered something further about his need to interact frequently with the Vice President in Washington. My job in the nation's capital did not ordinarily include such high-level associations.

A Secret Service agent from the Washington detail came back from the President's car escorting Nellie Connally, the governor's wife. There was no room for her in the President's car, which was a five-passenger model, the same as the Vice President's car. The President and Mrs. Kennedy and Governor Connally would ride in the rear seat of the President's car. The driver and agent Roy Kellerman would be up front. So there was no place for Mrs. Connally. But the Vice President's car was now reserved for the Johnsons, Yarborough, and, of course, Johnson's Secret Service agent and driver. The senator showed signs of relinquishing his seat to the lady. O'Brien, his face working, quickly moved in. To accommodate larger occupancy of the car, he ushered Mrs. Connally into the middle of the front seat. The Vice President and Mrs. Johnson came out of the hotel and approached the motorcade. O'Brien stepped back as Mrs. Johnson entered the car, and I stepped forward.

"Here is your seat, Mr. Johnson," I said cheerfully. He stared down at me while he struggled into a coat held by Secret Service agent Rufus Youngblood. The Vice President climbed into the car. The deed was done. Up ahead, the Kennedys and Governor Connally settled into their white convertible, which, Agent Howard recalls, had been borrowed by the Secret Service from professional golfer Ben Hogan. There were waves and cheers from the onlookers. The motorcade to Carswell began. Riding in a Secret Service car, Howard was pleased to see Tarrant County's "Mounted Posse" out in force to supplement police on foot. Rain had canceled the planned presence of these deputies on horseback along the incoming route the night before. There was, Howard recalls, an unscheduled stop by the presidential cavalcade along the way. In the northwest suburb of River Oaks, the line of cars paused while the President spoke to some nuns and a group of schoolchildren.

Ross Wilder, my helper from GSA's Dallas office, and I drove to Carswell by a different route to arrive at the air base before the motorcade did. The departure committee, formerly the welcoming committee, was already in place by prearrangement. It did its duty. Thousands of people behind the barricades raised their voices as the presidential jet took off for Dallas at 11:25 a.m., about thirteen minutes away. Members of the departure committee faces smiling, sought me out, and shook my hand. I experienced a surge of euphoria, which I would recognize later as the common feeling of advance men watching a President's plane take to the air after a successful "stop" with no untoward incidents.

We drove back to the Hotel Texas, and I made a reservation for a commercial flight home. Jerry Bruno, who had made the pre-advance of the Texas trip, telephoned from Washington, and Moyers called from Austin. Each wanted to know how the morning had gone. I told them it went well. After giving these assurances, I sat down at my portable typewriter and wrote a one-page final report on JFK's Fort Worth visit. Then I lay down for a nap.

I dozed off. Suddenly, there was a furious knocking on the door.

"Turn on your radio," Ross Wilder's voice shouted. "Your boss is shot. Turn on your radio."

I switched on the hotel radio and let him in. Bulletin followed bulletin. A voice said that two priests emerging from a Dallas hospital room had confirmed that President Kennedy was dead. We sat in stunned silence. After a while I packed up my belongings and advance-related papers. Secret Service agents Duncan, Hall and Howard were gone, racing down the thruway in a sheriff's car to join their fellow agents in Dallas. Rubley was already there. He had driven to Dallas and had been in the motorcade there. I had lost track of Harnett. There was nothing for me to do in Fort Worth. Ross Wilder drove me to Love Field in Dallas for the flight home. I had a middle seat in the plane. My sobs would not stop. Passengers on either side began to show alarm. Finally, I told them: "You will have to put up with this. I was in Texas for the President."