Return to Sender

U.S. Censorship of Enemy Alien Mail in World War II

Spring 2001, Vol. 33, No. 1

By Louis Fiset

© 2001 by Louis Fiset

As the Japanese censor is away again I write this in English.

— Iwao Matsushita1

On December 19, 1939, the thirty-three-thousand-ton German cruise ship SS Columbus, six days out of Vera Cruz, Mexico, was challenged by a British man-of-war while attempting to escape a naval blockade in international waters off Cape May, New Jersey. Unable to outdistance its pursuer, the Columbus's crew received orders from Berlin to scuttle the ship. The U.S. naval cruiser Tuscaloosa, on neutrality patrol, was trailing the two ships and picked up the life-jacketed seamen. It deposited the 574 survivors at the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) immigration station on Ellis Island, New York, for temporary detention until deportation procedures could be undertaken to repatriate them.2

Other ships flying Axis colors in territorial waters were also seized and their crews detained. The Italian passenger liner Il Conte Biancamano, for example, was homeward bound from Valparaiso on a scheduled Latin America route when it found itself trapped in the Panama Canal Zone at the outbreak of war in Europe. The U.S. neutrality patrol impounded the ship and confined its crew on board for the next eighteen months before finally transferring the seamen to Ellis Island in early 1941. The Italians joined a large group of German seamen, including the Columbus crew, as well as a group of Italian Pavilion employees from the 1939 New York World's Fair. In all, nearly 1,700 Axis noncombatants faced an uncertain future on Ellis Island in a country not yet at war.

These episodes preceded U.S. entry into World War II by more than two years and marked the beginning of its involvement in the detention and internment of noncombatants in the global conflict. They also led to an elaborate program to censor the personal and business mail of detainees and internees of war. Censorship would eventually involve the INS, the Office of Censorship, and the Provost Marshal General's office.

Numerous attempts to repatriate the "distressed seamen" from the Columbus failed when safe shipping could not be secured. Ellis Island was becoming overcrowded. In January 1941 the INS took over a former Civilian Conservation Corps site adjacent to the U.S. Marine Hospital on the Public Health Service reservation at Fort Stanton, in southern New Mexico, and converted it into an enclosed detention encampment for the Columbus crew.3 Later in the year, the INS acquired two military installations from the War Department: Fort Lincoln, near Bismarck, North Dakota, and Fort Missoula, four miles southeast of Missoula, Montana. It expanded them into detention stations that, with double bunking, could each hold more than two thousand prisoners. Should the United States go to war, these enlarged encampments would provide facilities for the internment of enemy alien residents whose records showed allegiance to the enemy. In May 1941 Fort Lincoln began to take on German crews, while the Italian crews and the former World's Fair workers headed for the high desert country in Montana under armed guard.4

INS Chief Patrol Inspector A. S. Hudson, administrator of the Fort Lincoln Detention Station, was soon chafing at the pro-Nazi sentiments of his new charges and had concerns over the strong pro-German views of many immigrant and second-generation German Americans residing in the area. Consequently, he sought authorization to bring in a full-time German-speaking intelligence officer to eavesdrop on the detainees and to gather information on the nearby populace. Some of the citizenry, he feared, might assist in escape attempts. Intelligence work, he argued, should also include examination of the detainees' incoming and outgoing mail in order to determine their attitudes.5

Two weeks later, Hudson's new intelligence officer arrived, INS employee M. A. Gerspacher. A naturalized German, he was under orders to open, read, and if necessary, censor detainee mail in a "discreet" manner.6 Discretion was important because of the flimsy authority the INS drew upon to justify this illegal activity. According to Lemuel B. Schofield, special assistant to the attorney general,

The Post Office Department takes the position that once a letter addressed to aliens in the legal custody of the INS is delivered to the proper representative of this Service it is "out of the mails," and that in so far as the postal laws and regulations are concerned what this Service does with such mail is a matter for this Service to determine. The same holds true of outgoing mail.7

On the basis of this opinion, Hudson and his staff set up index cards for each detainee, recording on them the names and addresses on all outgoing mail and the writers' names, addresses, and dates of arrival on all incoming mail. This practice would soon become standard procedure at all the INS camps. A sampling of mail was to be opened and read. In addition, the chief patrol inspector ordered incoming packages inspected for unspecified contraband prior to delivery to the Germans.

Despite Hudson's eagerness to gather intelligence on his charges, by the end of August Inspector Gerspacher was opening the incoming mail of only four detainees and the outgoing mail of four others.8 Hudson's superiors determined this level of activity to be inadequate and on August 29 sent orders for him to increase the percentage of mail to be examined. Specifically, Gerspacher was to read as much mail as he could manage and to sample each detainee's mail. Hudson directed him to pass on translations of letters appearing to contain information in connection with espionage, sabotage, and related neutrality matters. The yield from this trial would determine whether the INS should hire additional German-speaking censors to undertake reading all the correspondence.9

Hudson's counterparts at Fort Missoula and Fort Stanton did not share his suspicions because nearby Missouleans expressed less pro-Axis sympathy, and the area surrounding the former CCC compound was sparsely populated. Evidence has yet to surface to suggest that detainee mail at these INS camps was monitored or opened prior to U.S. entry into the war.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), however, was in the mail-monitoring business. Director J. Edgar Hoover authorized his agents, in cooperation with the Post Office Department, to quietly go through the personal mail of a select group of resident aliens on whom it was building dossiers because of their potential threat to national security. As early as the fall of 1940, local agents were recording the names and addresses of individuals corresponding with immigrant Japanese leaders.10 The likely purpose of this activity, for which administrative but no statutory authority existed, was to uncover a suspected network of espionage agents operating outside the country with whom members of the alien community in the United States were believed to be cooperating.

In one case, the FBI placed a thirty-day cover on the personal mail of Iwao Matsushita, a scholarly immigrant Seattle leader with alleged ties to the Japanese Chamber of Commerce. This business organization was listed as one of more than three hundred potentially subversive Japanese groups then operating in the United States.11 When surveillance, beginning February 27, netted a single letter from Japan, the order was renewed for an additional thirty days. During this period Matsushita received five letters from family members in Japan and one domestic letter from a male with a Japanese surname. Follow-up field reports on the unsuspecting Matsushita provide no indication that the bureau was aware what personal, business, or political relationship the writers had with him.12 It appears the FBI, unlike inspectors at Fort Lincoln, was not opening and reading this correspondence.

Snooping into the private affairs of resident aliens through their mail was one of many means by which U.S. intelligence agencies collected information on potential enemy aliens prior to the war. Outright censorship of enemy alien mail and seamen's mail would begin in earnest following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, with the INS taking the lead.

Within an hour after Congress's declaration of war on Japan on December 8, 1941, Attorney General Francis Biddle brought to President Franklin Roosevelt a proclamation declaring that "an invasion has been perpetuated upon the territory of the United States by the Empire of Japan." Further, all resident Japanese nationals over the age of fourteen in the United States and its possessions were immediately "liable to restraint, or to give security, or to remove and depart from the United States." This and companion restraint and removal proclamations declaring Japanese, German, and Italian nationals to be enemy aliens derived their authority from the first Alien Enemy Act of 1798, as amended in 1918, which gave the President absolute power over enemy aliens in time of war. With the President's three signatures, 314,105 German, 690,551 Italian, and 47,305 Japanese nationals residing on the U.S. mainland became enemy aliens.13 In addition, the German and Italian seamen, whose official status was "excluded aliens awaiting repatriation," now became enemy aliens subject to internment for the duration of the war. The FBI's emergency arrests of enemy aliens began before sundown on December 7 and were carried out under authority of a blanket presidential warrant signed by Biddle.14

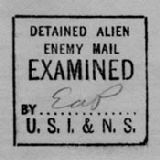

By the last day of 1941, 2,405 enemy aliens were in INS custody. In addition to the Fort Stanton contingent, 633 Japanese and 28 Italian nationals shared the Fort Missoula grounds with nearly 1,000 Italian seamen and World's Fair workers, while 104 German resident aliens joined 300 German seamen behind barbed wire on a bleak North Dakota winter landscape at Fort Lincoln.15 Arrest and detention and eventual internment orders for many others continued well into the next year. The growing numbers placed multiple strains on INS personnel, not the least of whom included a cadre of Japanese, German, Italian, and Spanish language censors who were under orders to examine 100 percent of the detainees' incoming and outgoing mail.16

No statutory authority to open and censor enemy alien mail existed in the opening days of the war because the First War Powers Act, authorizing a censorship program, was not in effect until December 18. Executive Order 8985, signed by Roosevelt on December 19, authorized creation of the Office of Censorship. From this day on every letter that crossed international or U.S. territorial borders from December 1941 to August 1945 was subject to being opened and scoured for details.

Censorship predates America's independence. The First Amendment, guaranteeing freedom of the press, arose in part from censorship imposed by the British. Subsequent interpretations by the courts resulted in the protection of most forms of communication, including the mail; nevertheless, threats to the first amendment have periodically occurred throughout the nation's history. In the antebellum South, for example, a number of postmasters contributed to press censorship by refusing to deliver antislavery material, preferring the risk of federal penalties over mob attack. During the Civil War, Secretary of State William Seward refused to permit journals criticizing the administration into the mail stream, and some states banned mail delivery of newspapers such as the New York World, the Chicago Times, and the Cincinnati Enquirer.

The first systematic program to censor the mail in the twentieth century was developed by the British during the Boer War in South Africa (1899 - 1902). The lessons learned in that war led to widespread censorship of international mail during World War I. By the time the U.S. Army Expeditionary Forces finally arrived on the European continent in 1918, the British had evolved a highly effective system of mail censorship, as well as cable and telephone censorship, which they passed on to their American allies.

Two decades later, after declaring a national state of emergency when Hitler's forces rolled into Poland on September 1, 1939, Roosevelt was presented with several proposals of civilian and military plans for wartime censorship based upon thwork of the architects of censorship in the previous world war. On June 4, 1941, he approved a plan for national censorship of international communications and ordered the U.S. Army to develop a modern program for censoring the mails entering and leaving the United States. He also charged both the FBI and the Office of the Postmaster General with concurrent planning and directed the U.S. Navy to begin formulating a plan for censoring cable, radiotelegraph, and radiotelephone circuits.

Wartime censorship creates a multiple advantage for nations that engage in it. One objective seeks to deprive the enemy of information, as well as tangibles such as funds and commodities. A second aims to collect myriad intelligence that can be turned against the enemy.17 Censorship also engages the populace; every letter is an exercise in good citizenship, and acquiescence to its regulations represents a contribution to the war effort. In World War II, postal, cable, broadcast, and press censorship affected the lives of civilians and military personnel in virtually every country of the world, both belligerent and neutral. World War II produced the world's largest censorship operation—one that has not yet been matched.

On December 8, 1941, the secretary of war ordered corps area commanders to inaugurate censorship of telephone and telegraph wires crossing international borders. Three days later, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, on presidential authority, helped set up a postal censorship program to be carried out by the War Department. He was ordered to hold this temporary position until his civilian replacement could be chosen.

The First War Powers Act granted the President broad powers in prosecuting the war and specifically addressed censorship:

Whenever, during the present war, the President shall deem . . . public safety demands it, he may cause to be censored under such rules and regulations as he may, from time to time establish, communications by mail, cable, radio, or other means of transmission passing between the United States and any foreign country.18

In creating the Office of Censorship, the President conferred upon its director the power to censor international communications in "his absolute discretion." This individual was to be given absolute control over cable traffic, the mail, broadcasting, and the press. His choice for director was Byron Price, a fifty-year-old newspaperman from an Indiana farming family who had served more than twenty years in the nation's capital and, subsequently, as executive news editor and acting general manager of the Associated Press. The wire service was his passion. In a 1942 interview he admitted that the AP was a religion for him.19 Well known among Washington officials, Washington correspondents, and newspaper publishers and editors throughout the country, he was, nevertheless, a political nonpartisan.20

Following his appointment, Price expressed his personal view on the task he was about to undertake:

Any approach to censorship in a democratic country is fraught with serious difficulties and grave risks. . . . The word itself arouses instant resentment, distrust and fear among free men. Everything the censor does is contrary to the fundamentals of liberty. He invades privacy ruthlessly, delays and mutilates the mails and cables, and lays restrictions on public expression in the press. All of this he can continue to do only so long as an always-skeptical public is convinced that such extraordinary measures are essential to national survival. The censor's house is built on sand, no matter what statutes may be enacted, or what the courts may declare.21

News management under Price's watch was voluntary, as American editors and broadcasters were encouraged to impose self-censorship.22 Postal and cable communications, however, were to be rigidly censored. Postal censorship operations had begun on December 12, 1941, prior to Price's appointment, with army personnel and a few civilians slitting open handfuls of letters. One week later, now having statutory authority, the staff included 349 individuals employed in censorship field stations stretching from New York City to Honolulu. From then on, postal operations expanded rapidly, reaching 3,547 censors on March 15, 1942.23 At its peak, in September 1942, more than 10,000 civil service employees opened and examined nearly one million pieces of incoming and outgoing overseas mail each week at eighteen censor stations and substations throughout the United States and its territories.24

While the Office of Censorship was gearing up operations, U.S. civilians abroad were being rounded up and interned in increasing numbers by enemy forces throughout Asia and Europe. Seeking guarantees for their safety and security, Secretary of State Cordell Hull proposed to Germany, Italy, and Japan through their protecting powers that interned civilians on both sides of the conflict should come under the same protections to be provided prisoners of war according to the guidelines set forth in the Geneva Convention of 1929.25 In time, all the warring nations agreed to the proposal. The war convention spelled out the rights, privileges, and obligations of soldiers in captivity, which were now to be applied to civilian detainees and internees. With respect to contact with the outside world during their captivity, individuals must be allowed to send and receive letters and postcards in their native language. Further, censorship of their outgoing letters and postcards, which could be limited, should be carried out expeditiously. These few principles provided the basis for sets of rules and regulations later written by the INS censorship division, the Office of Censorship, and the Provost Marshal General's staff.

The INS had a keen interest in gaining access to its detainees' correspondence because it might help monitor inmate morale. Bert Fraser, the INS officer in charge at Fort Missoula, was no doubt relieved to learn that spirits were high among his issei (immigrant Japanese) charges at the close of 1941, who communicated changes in their situations to family members left behind. The statements of four detainees are typical of those Fraser's staff compiled:

We have radios, newspapers, entertainments, stores and hospital.

Your daddy is a captive of Uncle Sam but is not complaining.

Everyone has spring mattresses and the dining room is like Seattle Civic Auditorium and food is real good.

It is cold here but everything is nice and sanitary . . . clean sheets, mattresses, ample food, treatment generous and courteous.26

Such optimism might be unexpected from a group of individuals having just lost their civil liberties and many their livelihoods. Perhaps these statements were merely attempts to reassure their anxiety-ridden families at home. But they may also provide examples of self-censorship. Letter writers knew from the outset that their outgoing letters, submitted to headquarters in unsealed envelopes, would be read by their captors. Fear that their only connection to the outer world could easily be cut off no doubt contributed to conformity with the rules.

Camp administrators initially required that all outgoing letters be written in English because of the unavailability of staff censors proficient in Japanese, German, and Italian. Thus, many issei who could communicate only in Japanese or who could not find a scribe to write in English on their behalf found themselves completely isolated. Since this was a violation of war convention guidelines, the INS scrambled to find censors for its ethnically diverse population even as FBI raids continued to augment existing populations of detained enemy aliens attempting to communicate back home. In addition, interpreters would soon be needed for upcoming loyalty hearings, which would determine whether detainees were to be released or ordered interned for the duration of the war.

The INS sought people with bilingual skills, including German, Italian, Spanish, and Japanese. Many citizens and loyal aliens were fluent in the European languages, and recruiters had less difficulty filling these slots than those requiring Japanese. Individuals fluent in Japanese were largely the immigrant generation who, as enemy aliens, were ineligible to serve. Soon, INS, Office of Censorship, and army recruiters learned how few children of the issei, the citizen nisei, could speak or write the language. In time, civil service salaries paid to linguists would reflect the scarcity of Japanese censors. In the meantime, the government turned to resident aliens of Korean ancestry to fill most of the slots. The Korean populace had been required to learn Japanese under duress by their occupiers, who had been suppressing Korean culture since 1905.27

Incoming mail for Fort Missoula's Japanese population was accumulating rapidly as 1942 dawned, with string-bound bundles approaching the ceiling in a ten-by-fourteen foot storage room. The task of clearing this backlog while attempting to stay current with the daily inflow and outflow would produce long workdays.28 The censor arrived on January 21, one of the few Japanese Americans recruited early in the war. While awaiting his arrival, INS administrators, with assistance from the fledgling Office of Censorship, wrote a preliminary set of rules and regulations to guide censors and letter writers, which they planned to modify over time. Each of the detention stations received copies, and key portions relevant to letter writers were translated into Japanese and Italian and posted on bulletin boards.29

Initially, detainees were allowed to send two letters a week, one of which had to be in English. In addition, camp officials allowed four postcards if written in English, or two in a language other than English. The length of letters was limited to twenty-four lines, postcards to seven. These restrictions, which changed from time to time, were imposed to buffer censors from overwhelming volumes of outgoing mail. However, as the censors soon learned, no restrictions were imposed upon the frequency and length of incoming correspondence, nor did such restrictions apply to correspondence with attorneys or business associates. When censors fell behind with their work, tighter limits were temporarily imposed. In one case, writers were permitted two outgoing letters a week in any language, but their weekly quota of postcards was reduced to one.

The censors were trained to eliminate objectionable matter from correspondence and to glean information that might be useful to the war effort. The regulations distributed on January 7, 1942, listed twenty-two subjects that would lead to deletions or condemnation of the letter. For example, writers were forbidden to complain about camp conditions or the individual treatment they received, including medical care. Numbers of detainees in camp, guard strength, detainee transfers, and other aspects involving camp policies could not be communicated. Criticism of any government was forbidden, and enemy propaganda and outright false statements about any aspect of writers' circumstances would not be allowed to pass out of camp. Writers were threatened with loss of writing privileges or worse for repeat violations of the rules.30

The censors had at least three methods at their disposal of preventing objectionable information from reaching their targets. They were applied both to incoming and outgoing mail. First, scuffing the paper, then running a bead of impenetrable black ink could obliterate forbidden text. A second technique involved cut outs with a sharp blade. A letter heavily censored by this method might resemble a piece of crude lace. Finally, when letter writers pushed censorship regulations to the limit, examiners were authorized to condemn the entire letter and return it to the sender.

Despite the rigid regulations, INS censors passed into the mail stream more than 98 percent of the letters they examined either with no excisions or with minor cutouts involving a single word, phrase, or sentence. The following passage from a letter written by an issei internee at the Fort Missoula camp is typical of minor infractions of the rules, which would not threaten a writer's privileges:

The other day we had an evening of entertainment by fellow detainees in a recreation hall, which is large enough for over 1,000 people. [CENSORED] did a comic dance, wearing a gorgeous costume painted by Mr. [CENSORED]. He is enjoying himself & others by painting pictures.31

A small fraction of letters, however, contained information of sufficient interest to pass along for analysis. A wife writing to her husband about a measles epidemic at the Puyallup Assembly Center for former Seattle residents of Japanese ancestry, for example, included statements that were inflammatory toward medical care being provided there and were later proven false. The censor excised the whole passage and prepared a report (submission slip), which included the offending text. Authorities then followed up by investigating the charges.

Aware that heavy restrictions were being placed on their communications, some writers devised means to evade censorship. Perhaps the most motivated to do so were German nationals from Latin America, where Third Reich sympathies ran high. Common methods of evasion involved placing messages on the backs of postage stamps affixed to the envelope and writing with invisible ink on the insides of envelopes that had been steamed open, unfolded, then resealed. The ancient device of invisible inks could be employed by using common organic fluids available to the inmates such as milk, starch, citrus juices, or urine. Each could be applied with a toothpick quill. An addressee in the know could char the message into visibility with heat or expose it by dipping the paper into appropriate water-soluble chemicals.32 Since attempts to evade the censors were common, a special laboratory was set up in Washington, D.C., and manned by Office of Censorship personnel, Here they applied chemical, x-ray, and other analyses designed to maintain the embargo on contraband words.

Such chemical dragnets were porous, however, since only a sampling of the enormous volumes of mail could possibly be analyzed. At most, the entire correspondence of a few individuals trafficking in forbidden text could be analyzed because of personnel and laboratory space limitations. Other efforts to make messages difficult to conceal proved more successful. The Provost Marshal General's office created a letterform for international correspondence in early 1942, modeled after POW stationery it had helped design earlier. Being stationery as well as its own envelope, it employed a sensitized, glazed paper designed to make writing impossible to hide. The 6-by-14-inch sheet of lined greenish paper was designed to be folded into quarters, with a tuck-in-tab flap, thus requiring no gummed seams. Postage stamps were prohibited. The letterforms provided for twenty-four lines of text. When properly folded, the address side of the unit displayed large, bold letters spelling out INTERNEE OF WAR. This was designed to help mail handlers spot internee mail more easily.

The first internee of war letterforms went into production in mid-1942. In December the INS placed an order for 100,000 copies, to be distributed to its various camps and immigration stations.33 The letterforms soon found widespread use, both in INS and army internment camps, and special permission had to come from camp officers in charge to use alternative stationery for business letters or for authorized enclosures. This stationery frustrated some attempts to evade censorship, and by providing space for exactly twenty-four lines, fewer communications were returned to the writer because of failure to comply with length restrictions.

As the Office of Censorship gained efficiency and its civil service employees took on increasing volumes of international mail, correspondence of enemy aliens under INS custody was diverted to the postal censor operating closest to the INS facility. Outbound Fort Missoula mail, for example, was forwarded in sealed packets to San Francisco; Fort Lincoln mail went to Chicago; and Fort Stanton mail to the postal censor at San Antonio.34 There, mail was subject to a second round of censorship. Internee mail began to pose special problems not encountered with ordinary international mail. They were permitted to send and receive letters from Germany, Italy, and Japan in conformance with war convention guidelines, whereas postal service through regular channels had been suspended. Routing of POW and internee mail into and out of enemy-occupied territory posed both a threat to national security and an opportunity to gain important intelligence from the homeland.

To address these unique concerns, the Office of Censorship hosted a conference in Washington, D.C., on February 27, 1942. The agenda was set to discuss the handling of POW and internee mail and to set up a special censorship unit at one of the district field stations for handling the international mail of prisoners of war and enemy aliens. Attendees included military intelligence officials and representatives of the Post Office Department, the International and American Red Cross, and the Provost Marshal General's office. Conferees agreed that the new POW unit, subsequently set up at the Chicago censor station, should examine 100 percent of the international mail of both POWs and detained and interned civilians. The Provost Marshal General's representative strongly suggested that POW unit censors also examine both incoming and outgoing domestic mail of enemy alien civilians in the army internment camps. This suggestion was tabled, however, because the Office of Censorship, at this stage of operations, had neither the statutory authority to censor domestic mail of any kind, nor sufficient personnel and adequate floor space to handle the increased workload that would eventually result.35

The new prisoner-of-war unit began operations in May 1942. Office of Censorship censor stations were ordered to forward all POW mail, as well as the international mail of detainees and internees, to the Chicago station. INS officers in charge received instructions from the central office in Philadelphia to forward to the POW unit under locked pouch all international mail of civilians under its jurisdiction. Its censors could open and read the mail prior to sending it on but were to avoid making deletions or excisions that might elicit an international complaint of double censorship and lead to reprisals against interned U.S. nationals in enemy territories. In June the Office of Censorship distributed the first edition of its regulations governing censorship and disposition of POW and enemy alien mail, regulations that differed in small but significant details from the INS regulations issued the previous January. The differences produced many interagency headaches and would soon affect the transmission of the mails and hence the morale of the internees of war.36

The populations at the Fort Lincoln and Fort Missoula detention stations, as well as at a newly opened camp located at Santa Fe, New Mexico for issei from the Los Angeles area, began to decline in the spring of 1942. Detainees were released, paroled, or handed over to the army for internment following their loyalty hearings. By the end of 1942, 1,186 German, 2,033 Japanese, and 227 Italian resident enemy aliens were in army custody, fenced off in remote corners of military reservations. The enemy seamen, on the other hand, totaling about 2,000, stayed put under INS control.37 The army internees found their new daily routines more restricted than the less formal regimens they enjoyed in the INS camps. One change for the worse arose from yet a third set of mail rules and regulations issued by the Provost Marshal General's office.38

Until mid-November 1942, local army base personnel examined the outgoing domestic English-language mail, then forwarded it in bags to local post offices for placement into the mail stream. Examiners were ordered to make no deletions or excisions. If suspicious information of intelligence value was uncovered, censors were to forward individual letters to the Provost Marshal General's office in Washington, D.C., for further examination.39 Foreign language domestic mail and, of course, all mail addressed abroad, had to go to the POW unit for censorship. During peak periods or when higher priorities took headquarters personnel away from censorship duties, English-language domestic mail was to be forwarded there as well.

With domestic mail now pouring in to the POW unit, which by now had moved from Chicago into bigger quarters in the New York censor station, the Office of Censorship was now engaging in activities for which it had no statutory authority. Nevertheless, the Geneva Convention permitted censorship of all POW and internee mail without regard for its destination. This new policy, therefore, raised few questions. Emboldened, in November 1942 Director Price arrogated to his office the handling of all internee mail originating in army internment camps and invited the INS commissioner's office to submit the domestic mail of detainees and internees under his jurisdiction, as well.40

This change in protocol pleased Price because it would help reduce inevitable gaps in useful intelligence that resulted when multiple examiners, working under three sets of guidelines, culled information of varying perceived importance and that may or may not have been passed on to appropriate intelligence specialists. For the internees, however, the change in policy led to increased delays in transmission of their domestic mail. Moreover, because POW unit censors had to absorb the new workload without an increase in staffing, their international mail no doubt slowed, as well.

Under the new procedures, all POW and outgoing internee correspondence in army camps had to first go to the POW unit in New York, where it competed with all other mail for the attention of the examiners. Similarly, incoming mail from all sources had to first go from the camp to New York for censorship before retracing its steps back for delivery to the addressee. Multiple complaints by internees to their captors about the sudden increased delays in receiving their mail caused the Office of Censorship to make a change in policy. It rented a post office box at New York City's main post office to receive all incoming mail for the camps directly. Internees were provided preprinted form letters with which to inform correspondents of the new address.41 For the time being, the new policy reduced some of the delays in delivering the mail.

The POW unit was busy. During the first six months at the Chicago censor station, 141 examiners manned the tables to censor the mail. At any one time, thirty-eight men and women were processing more than fifty pieces of mail each workday. For every sixty-four letters opened and read, one submission slip was prepared. Bits of intelligence, large and small, important and not so important, were collected from 2,120 pieces of mail that were subsequently released, returned to the sender, or condemned.42

With the INS central office and Office of Censorship still adhering to conflicting sets of regulations, administrators frequently found themselves at odds over censorship issues. The POW unit held to a more rigid interpretation of the guidelines, while INS camp officials, in everyday physical contact with the letter writers, attempted to create a balance between enforcing the rules and maintaining morale among their charges. At times, INS and Office of Censorship censors were at loggerheads over what information should be allowed to pass. Local censors passed many letters only to see them returned by the POW unit censors weeks or even months later. These experiences contributed to a declining prisoner morale, since letter writing from the lonely outposts was the only access to loved ones in the outer world.

INS administrators themselves contributed to the problem by their repeated failures to inform the POW unit of policy changes that might conflict with the established Office of Censorship regulations. In one case, Fort Missoula camp commander Bert Fraser restricted the number of outgoing Italian-language letters in order to provide temporary relief for his overworked Italian-speaking censor. A seaman, informing his correspondent that he could now write only one letter in Italian each week, had his letter returned by a POW unit censor accompanied by a note that he was misinformed of the regulation permitting two letters in Italian.43

Even small violations of the conflicting rules could result in a letter being returned—references to the cold weather, salutations or messages to a third party, inclusion of seemingly harmless personal photographs, or writing a twenty-fifth line of text.

In late November 1942, Fraser made attempts to clarify and coordinate the rules between his superiors and the Office of Censorship, imploring them to employ more liberal censorship on behalf of the internees. "Letter writing to their homes," he wrote, "is one of the greatest 'salves for their sores.'" An opportunist, he recommended allowing internees to write more freely to enable camp and POW unit officials to better assess morale and to more easily identify the "beefers," or troublemakers.44

For its part, the Office of Censorship felt that censorship in the INS camps was too lax and encouraged the service to tighten its controls and submit all domestic mail to the POW unit. In Director Price's view, the value of information gathered on behalf of the war effort, no matter how small, superseded any peace of mind that letter-writing might bring to enemy alien internees of war. Price applied pressure on Willard F. Kelly, assistant INS commissioner for alien control, in an attempt to persuade the service to turn over the domestic mail of internees and detainees to his office. In one appeal, written in January 1943, he outlined his argument in detail:

The Prisoner of War Department endeavors to make the most of every source of information within its jurisdiction by an exclusive scrutiny of each letter which passes through its hands, in order to extract every item of information which may be of value, both actual and potential. These items are carefully prepared and kept in the correspondence record of each detainee. A chain of information can gradually be forged which may be of value to the war effort. If, however, any letter in the chain of correspondence is permitted to reach its destination without passing through the New York Station, the continuity is broken. In consequence, the information already gleaned may be incomplete or rendered useless; an important piece of information may escape entirely; or future communications may be made unintelligible by allusions to matters which were contained in a previous letter which did not reach censorship.45

Price failed to persuade Kelly, who continued to oppose relinquishing internee domestic mail to the Office of Censorship because of the inevitable delays that would follow. He criticized the rigid set of rules applied by POW unit censors that often contradicted established protocols of INS censors and resulted in mail being returned. The following June, Kelly summarized his opposition to Price's repeated requests in a memorandum to his superior at the Justice Department, Edward J. Ennis, director of the Alien Enemy Control Unit:

We, of course, are not in a position to accurately estimate the value to the war effort of such mail examination but the undersigned doubts that any benefits to be derived therefrom would outweigh the disadvantages that would ensue. Perhaps the most serious and constant cause of complaints by detainees has been the handling of their mail, and comparatively slight delays in the past have contributed greatly to discontent and loss of morale in the camps. We are almost constantly receiving complaints or at least inquiries from the State Department and the two protecting powers relative to slowness in the delivery of mail, and the situation would be infinitely worse if all of the domestic mail were required to pass through the New York Office of Censorship.46

Kelly defended his unit's protocols, assuring Ennis that each piece of mail entering or leaving the detention stations was carefully scrutinized. His censors promptly notified POW unit officials with submission slips or forwarded whole letters whenever useful information appeared.

There was little Director Price could do to compel the INS to cooperate in the absence of statutory authority or a presidential directive. Since the INS, the Office of Censorship, and the army could not agree on one set of regulations, confusion reigned over what writers could and could not communicate. Invariably, it was the internees who suffered the consequences. One bright spot occurred in the spring of 1943, when internees under army control were returned to INS custody. Once the Provost Marshal General's office was out of the picture, only two conflicting sets of regulations remained in effect, reducing but not eliminating the inmates' letter-writing woes.

Although the INS remained steadfast in its refusal to forward internee domestic mail to the POW unit, in the summer of 1943 Kelly's office submitted to pressures by the Office of Censorship and the Office of Naval Intelligence to participate in a two-month experiment during which the POW unit would process the domestic mail of the Columbus crew still at Fort Stanton. Useful military information might be gleaned from this untapped resource, it was argued, and such a test would quantify delays in mail transmission caused by POW unit involvement. Since the seamen's domestic mail represented only a small portion of its total correspondence, Kelly gave his consent.47

The experiment, which began August 20, 1943, produced only two submission slips. Moreover, the average time required to process the seamen's mail was thirteen days, almost double earlier promises.48 The seamen protested loudly to the Swiss Legation, Germany's protecting power in the United States, which successfully intervened.49 This experiment ended Office of Censorship attempts to control the domestic mail of enemy aliens. However, efforts on the part of internees themselves to affect changes to the rules and regulations continued.

The internee of war letterform designed to discourage secret writing also brought complaints that censorship authorities had failed to anticipate. With its large block INTERNEE OF WAR insignia, the letterform identified the writer as an interned enemy alien to anyone whose eyes fell upon it. This often proved embarrassing to addressees, especially U.S. servicemen sons of Japanese, German, and Italian internees, many of whom, by mid-1944, were fighting in Europe and in the Pacific theaters. Fathers tried to get around this unwanted attention by affixing postage to ordinary envelopes containing their letters, thus disguising their correspondence as ordinary civilian mail headed to soldiers overseas. In some cases the district postal censor, complying with outstanding instructions to all postal examination units, returned these letters to the writers for failure to identify themselves as internees.50 Complaints by the soldiers' fathers led the Office of Censorship to modify its policy. Now writers corresponding with their sons were allowed to substitute ordinary stationary affixed with appropriate postage. The return address on each envelope would show the name of the internee, the post office box number of the camp, and the name of the post office. But writers were no longer required to include their internee serial number, the words "internment camp," or any other indication of the sender's imprisonment status. From then on, local censors examined the military-bound mail with unusual care since the POW unit would examine none of it. Thus, it received the same treatment as internee domestic mail.51

Concessions were also made for letters to siblings on the front. A U.S.-born wife of a German enemy alien interned at the Crystal City, Texas, camp for families requested permission to write to her brothers using ordinary stationery instead of the required letterforms. INS officials readily agreed, but the Office of Censorship insisted all such correspondence with siblings be handled as internee international mail and thus be sent via the POW unit in New York.52 This included correspondence between nisei internees and their brothers fighting with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Europe.53

Appeals by German internees writing to civilians in Latin America brought similar changes in the rules. However, because of the higher incidence of attempts to evade censorship prevailing along those mail routes, they were required to continue their use of the sensitized letterform. The Germans writers, however, were provided individual envelopes at the camp headquarters and were required to address them in the presence of an INS employee to prevent attempts to pass secret writing.54

Not all internees benefited from the rule changes, however. For example, the issei at Santa Fe received no such privilege when sending mail to their friends and family in Hawaii. In May 1945, despite prior approval by the Santa Fe camp's officer in charge, nearly eighteen hundred letters written by the issei on the internee letterforms were intercepted by the POW unit and returned when censors found them enclosed in ordinary airmail envelopes.55

While helping to resolve censorship problems in one area, the INS was creating problems elsewhere. As early as 1943, the service began to relax its hold on the captives, allowing small groups to live outside the internment camps and engage in group work projects while supervised by an appointed parole officer from the nearest INS district director. Most laborers were German and Italian seamen who were considered lower national security risks than the resident nationals under its jurisdiction. Among the locations where the seamen found outdoor work were Forest Service projects in Montana, Idaho, and Washington; gang work on the Northern Pacific Railroad in Montana, Washington, and North Dakota; and factory work at a Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Project located in Akron, Ohio.56

Although not physically confined to internment camps, the internees-at-large were nevertheless required to abide by rigid rules of conduct. They included censorship of their domestic and international communications, whether mail, cable, radio, telegraph, or telephone. The workers were free to use ordinary envelopes with their domestic mail, but like all internees, they had to use the sensitized letterforms on all international correspondence. The return address on each envelope was to include "c/o U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service," with the postal address of an officer chosen by the service. Such indicia would properly alert censors of their internee status. All outgoing mail was then to be forwarded unsealed by a designated representative of the employer to the nearest INS district director, who would relay the letters to the POW unit for examination. No restrictions on the number of outgoing letters were imposed, but internees-at-large were forbidden from informing correspondents that they were not actually in custody.

Compliance, of course, was difficult to enforce. Evasion of censorship was relatively easy if writers elected not to use the correct form of return address. Since postal authorities and other censorship stations handling international mail failed to recognize such mail as internee correspondence, much of it must have gotten through. On the other hand, mail to Germany and Italy could not get through if sent through the ordinary mail stream. The censorship net for internee-at-large mail remained porous throughout the war despite several attempts by a frustrated Office of Censorship to bring INS supervisors into line with its censorship regulations.57

Still another challenge arose for the censors in early 1943, this time in the relocation centers, which held in captivity more than 100,000 Japanese Americans and their immigrant elders from the West Coast. The War Relocation Authority (WRA), headed by Dillon S. Myer, former assistant chief of the Soil Conservation Service, ran these centers. Myer became convinced that "loyal" prisoners should be allowed to leave the centers and regain their complete freedom. "Disloyals" should remain confined in a segregated camp. To achieve this goal, in February 1943 the WRA initiated a loyalty questionnaire to the residents in all ten centers. Two loyalty questions required willingness to serve on combat duty in the armed forces and swearing unqualified allegiance to the United States while at the same time foreswearing allegiance to the emperor. They were so offensive to the residents that many nisei and issei refused to answer the questions or gave "no-no" answers. These people were subsequently separated out as "disloyals" and sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, which had been transformed from a relocation center for that purpose. Among them were nearly six thousand nisei who renounced their U.S. citizenship and would later seek expatriation.58 Many of them had received part of their education in Japan and were known as kibei.

Originally, correspondence coming from the relocation centers was off limits to POW unit censors. However, changing conditions caused the captors to look to the censors for help in gathering intelligence on the restive population. On July 16, 1943, Director Myer asked the Office of Censorship to provide him with intercepts from relocation center residents that might reveal attitudes toward center administrators as well as indications of rising pro-Japan militancy. Theodore F. Koop, assistant to Director Price, responded to Myer's request by agreeing to furnish material of interest from residents' international mail but instructed the worried WRA head that the Office of Censorship had no authority to provide him with intelligence culled from domestic mail. The real truth, however, was that the task of censoring the mail of more than 100,000 center residents would require a substantial increase in the number of Japanese- and English-language examiners as well as an accompanying budget to cover the extra volume of work. Qualified Japanese examiners would be difficult, if not impossible, to recruit. When informed that the volume of international mail involving relocation center residents amounted to less than 2 percent of their total correspondence, Myer dropped the matter.59

However, once conversion of Tule Lake was completed in the fall of 1943, pressure to monitor undercover activities increased as a pro-Japan faction arose and began to dominate the residents. The renunciants became a focal point of Myer's concerns.60 The most militant of the renunciants at Tule Lake were eventually weeded out and sent to INS camps. The INS, of course, had no legal jurisdiction over U.S. citizens. However, once an individual had renounced U.S. citizenship, his or her legal status converted to enemy alien. Thus renunciants fell under the jurisdiction of the INS, which had the authority to intern them and censor their mail.61

The population at Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, which had remained stable for nearly three years, began to swell in February 1945 as renunciants began to join the ranks of the German seamen. As of July 3, 1945, 1,516 of the group had been separated from their families at Tule Lake and sent to the all-male INS camps at Fort Lincoln and Santa Fe. By now, most of the permanent INS camps had shut down, with only Fort Lincoln, Santa Fe, and the family camp at Crystal City still holding Japanese internees. Two Japanese-language censors were brought in to handle the mail of the 650 bilingual transferees, many of whom chose to communicate in Japanese. Additional censors were hired for duty at the Santa Fe camp.

Upon their arrival at Fort Lincoln, the internal security officer informed the renunciants that they could communicate with friends and relatives, but only on personal matters of mutual interest. Reference to camp conditions must be avoided, and attempts to incite unrest would not be tolerated. Initially, many became recalcitrant, defying most orders and failing to comply with instructions regarding the mail. In turn, the censors condemned their correspondence.

Regulations prevented even laudatory comments about camp life. More important to WRA officials, however, was the need to prevent passing of information detrimental to the administration, which was coming under increasing attack both for mismanagement and for its poor handling of disciplinary problems at Tule Lake. The following excerpt was excised from a letter written by a nisei at Tule Lake to his kibei brother at Fort Lincoln and subsequently forwarded to INS central headquarters:

You know, they are trying to break up the clubs, and Kawabata sensei and the dancho were sentenced to 30 days in the center jail. They were taken for holding a meeting, but don't worry, we are carrying on just the same. Mom says don't ever change your mind.62

Both the WRA and INS wanted a blackout on general conditions of internment of those transferred to Fort Lincoln and Santa Fe and on the exchange of information relating to plans for expatriation. Initially, the censors at Santa Fe and Fort Lincoln were largely successful in shutting down this two-way correspondence, leading some writers to devise means to send secret messages in packages, such as packs of cigarettes that only appeared to be sealed. Others asked visitors to smuggle letters out of the internment camps and drop them in the mail at distant post offices. Individuals caught attempting to evade censorship faced time behind bars. One writer spent two weeks in the guard house after a censor discovered invisible writing on a piece of his outgoing mail.63 Others with greater imaginations were never caught. One couple cleverly sewed messages into the lining of clothes sent to the wife for mending.

By the end of March 1945, despite the vigilance of the censors, prevention of the exchange of information between the camps was a lost cause. Transfers of Japanese to Santa Fe and from Santa Fe to Fort Lincoln and visits to Fort Lincoln by Japanese who were free to write at will to Tule Lake made most attempts to keep secrets from the segregation center residents all but impossible. Seeing the futility before him, "Ike" McCoy, officer in charge at Fort Lincoln, requested permission from his superiors to end censorship of mail between the two camps. The central office dragged its heels, however, even after an additional one hundred Tule Lake renunciants arrived at Fort Lincoln during the first week of July. Censorship persisted at the INS camps well after the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought an end to the war.64

With Japan's surrender, the Office of Censorship discontinued examining international mail, including internee mail, and soon went out of business. The INS, however, continued to censor mail well into 1947, although modifying its regulations from time to time as conditions changed. On August 17, 1945, for example, the central office ordered the use of the internee letterforms discontinued and, except for renunciants' mail, relaxed most restrictions on content.65 Censors were to excise only malicious statements or statements known to be false.

Renunciants' mail frequently contained nationalistic sentiments and propaganda favorable to Japan. Some family members who refused to believe that Japan had lost the war revealed their states of mind in such letters, such as the following excerpt from a letter to the Santa Fe camp:

Regardless of what the newspapers or radio say, Japan has positively won this war. They have defeated the inhuman nation of United States and Britain. With the great object to be accomplished such as creating a great East Asia for prosperity our nation will never surrender. I am confident that they do not desire to stop fighting at the present time.66

The censor excised the entire statement.

Standing orders to examine renunciant mail were not rescinded until December 13, 1945, four months after the end of the war.67 By March of the following year, local camp administrators, who by now were autonomous on censorship matters, were concerned mostly about maintaining peace and security and winding down operations.68 Two months later, only the Crystal City camp remained open. The censor-translators were terminated by the end of the month, and all subsequent foreign-language mail was forwarded to the Ellis Island immigration station. Because residents continued to generate a large volume of mail, especially among the renunciant group endeavoring to settle their expatriation cases, the officer in charge continued to impose a one-page restriction on personal mail well into the summer. Clerical and matron personnel moved into the desks formerly occupied by the censors to read English-language correspondence for content of interest only to the local administration. Few, if any, excisions resulted.69

Following closure of the Crystal City camp in late 1947, the handful of enemy aliens still awaiting the end of their of deportation proceedings were transferred to Ellis Island, where their mail continued to be subject to examination. The INS controlled the number of letters and parcels dispatched by its internees until the last deportable enemy alien left the country in 1948.70

From 1941 to 1948 the FBI, the INS, the Office of Censorship, and the army legally tampered with the personal and business mail of more than nine thousand interned enemy aliens and Axis seamen and thousands more who were detained and later released.71 What the intelligence gatherers achieved through this large-scale invasion of privacy is difficult to measure. Certainly the censors must have passed on valuable insights into economic conditions, civilian morale, and disruptions to lives in the besieged countries of Europe and the Far East. Information of direct military value likely reached the censors through slips in attention by the enemy's own censors. Even offhand comments about the weather had military significance. Every bit of collected information added to a large mosaic that propagandists and military strategists interpreted to their advantage.

Given the circumstances of their confinement, internees in the U.S. had little access to direct information of military value to the enemy. Nevertheless, the censors were always on the lookout for statements of perceived injustice, abuse, or other behavior by civilians falling under the protection of the Geneva Convention. Should such information slip into the wrong hands, it might lead to repercussions against interned citizens of allied countries held in enemy territories. Camp administrators were continually vigilant about conforming with the terms of this international agreement regarding all aspects of captivity.

Censorship regulations frustrated and demoralized the internees and motivated them to protest the frequent disruptions in their mail. Although many of the mail delays must have seemed punitive to those with high emotional investments in their correspondence, few writers understood the complexity of postal censorship or appreciated the extraordinary volumes of letters that the limited number of censors were required to handle each week.

A more coordinated effort between the censor bureaucrats might have mitigated some of the complaints. It appears, nevertheless, that few attempts were made to single out one ethnic or racial group for punitive treatment by withholding mail or condemning letters. All groups seemed to have had their individual grievances against a seemingly indifferent system. However, when legitimate complaints were brought before the officers in charge or the protecting powers, changes in policy frequently followed, whether on behalf of the seamen or the civilian internees.

During times of armed conflict, civilians will continue to be incarcerated. With the Geneva Convention of 1929 serving as a guideline, World War II established the precedent for humane treatment of interned noncombatants, including their contact with the outer world. For some, such communication was, and will probably always be sustenance nearly as important as food.

Louis Fiset is an independent researcher whose special interest is the World War II experience of Japanese Americans. He is the author of Imprisoned Apart: The World War II Correspondence of an Issei Couple, and numerous articles.

Notes

1. Louis Fiset, Imprisoned Apart: The World War II Correspondence of an Issei Couple (1998), p. 243. This book records an unbroken correspondence between an immigrant Japanese couple who were imprisoned in separate camps for two years.

2. Numerous press accounts of the last day of the Columbus have been written. See, for example, New York Times, Dec. 20, 1939.

3. John Joel Culley. "A Troublesome Presence: World War II Internment of German Sailors in New Mexico." Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 28 (1996): 279–295.

4. As of December 1, 1941, Fort Stanton held 450 German seamen from the SS Columbus. Fort Lincoln's population included 285 German crewmen, and Fort Missoula held 912 seamen plus 70 former employees of the 1939 New York World's Fair.

5. A. S. Hudson to W. F. Kelly, June 20, 1941, box 11, file 1003/D, entry 291, General Files, 1942–45, Ft. Missoula, MT, Records of Enemy Alien Internment Facilities, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group (RG) 85, National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, DC.

6. Marginalia on original memorandum from Special Assistant to the Attorney General Lemuel B. Schofield to Kelly, Aug. 23, 1941, accession 85-58A734, Records of the Central Office (Central Records), box 2407, file 56125/27, RG 85, NAB.

7. Schofield to Hudson, June 30, 1941, box 11, file 1003/D, entry 291, General Files, 1942–45, Fort Missoula, MT, Records of Enemy Alien Internment Facilities, RG 85, NAB.

8. Hudson to Special Assistant to the Attorney General, Aug. 26, 1941, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2407, file 56125/27, RG 85, NAB.

9. Memorandum to Schofield from Kelly, Aug. 28, 1941, ibid.

10. Presumably the FBI was also monitoring the mail of German and Italian nationals who were also under suspicion as national security risks.

11. Bob Kumamoto, "The Search for Spies: American Counter-Intelligence and the Japanese American Community, 1931–1942," Amerasia Journal 6 (1979): 45–75.

12. FBI reports on Iwao Matsushita, May 14, 1941, and Dec. 18, 1941, accession 85-53A0010, Closed Legal Case Files, box 697, file 146-13-2-82-322 (Iwao Matsushita), General Records of the Department of Justice, RG 60, National Archives at College Park, MD (NACP).

13. Alien German and Italian figures are Justice Department estimates for 1940. See Tolan Committee, Fourth Interim Report, National Defense Migration, H. Rept. 2124, 77th Cong., 2nd sess., May 1942, table 2, pp. 229–230. For the 1940 foreign-born Japanese census, see U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, "Sixteenth Census of the United States—1940, Population: Characteristics of the Nonwhite Population By Race" (1943), table 1, p. 5.

14. Francis Biddle, In Brief Authority (1962), p. 207; U.S. Congress, House Rept. 2124, 77th Cong., 2nd sess., 1942, in Roger Daniels, ed., American Concentration Camps (1989), Vol. 5; Morton Grodzins, Americans Betrayed: Politics and the Japanese Evacuation (1949), pp. 232–233.

15. "Report of Enemy Aliens in Temporary Detention, December 31, 1941," accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2410, file 56125/35, RG 85, NAB.

16. The number of enemy aliens under INS jurisdiction reached a peak of 9,404 on June 30, 1943. By this time the INS was operating seven permanent internment camps and numerous temporary facilities. See "History of the Prisoner of War Unit for the First Six Months of 1943," box 1209, Records of the Office of Censorship, RG 216, NACP.

17. U.S. Office of Censorship, A Report on the Office of Censorship (1945), p. 1.

18. Section 303 of the First War Powers Act. This passage originated with the Trading with the Enemy Act, Oct. 6, 1917, 40 Stat. L. 411, 413, chap. 106, sec. 3, par. d.

19. Cecilia Ager, "Cecilia Ager Meets the Censor," PM, Apr. 20, 1942.

20. Office of Censorship, "A History of the Office of Censorship: Censorship As Viewed from the Office of the Director," Vol. 1, pp. 32–33, entry 4, box 2, RG 216, NACP

21. A Report on the Office of Censorship, p. 1.

22. For an examination of the Office of Censorship, see Thomas Harold Berg, "Silence Speeds Victory: The History of the United States Office of Censorship, 1941–1945" (Ph.D. diss., University of Nebraska, 1999). For a comprehensive study of the press and broadcasting divisions, see Michael Steven Sweeney, "Byron Price and the Office of Censorship's Press and Broadcasting Divisions in World War II" (Ph.D. diss., Ohio University, 1996).

23. "Planning for and Operations of Postal and Wire Censorship: June, 1941–March 15, 1942," p. 28, historical file (Postal Censorship), 1934– 1945, History of Postal Censorship, box 1209, RG 216, NACP.

24. Office of Censorship data cited in Wilfrid N. Broderick and Dann Mayo, Civil Censorship in the United States during World War II (1980), pp. 23– 27.

25.Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, Vol. 1: 1942 (1960), p. 792.

26. Collaer to Kelly, Dec. 29, 30, 1941, Field Records, Alien Internment Camps—Camp Missoula, file 1013/L (Publicity—Censorship), RG 85, NAB.

27. See Hyung-Ju Ahn, "Korean Interpreters at Japanese Alien Detention Centers during World War II: An Oral History Analysis" (masters thesis, California State University at Fullerton, 1995). The total number of Korean interpreters and censors employed by the INS and Office of Censorship is not yet known. It may have reached fifty.

28. Paul S. Kashino to the author, July 7, 1992.

29. "Administrative Order No. 27," Jan. 7, 1942, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2407, file 56125/27, RG 85, NAB.

30. "Administrative Order No. 27" and memorandum from H. D. Nice to Kelly, Jan. 24, 1942, ibid.

31. Iwao Matsushita to Hanaye Matsushita, May 1, 1942, in Fiset, Imprisoned Apart, p. 143.

32. For a discussion of innovative means to evade censorship, see David Kahn, The Code Breakers: The Story of Secret Writing (1967), pp. 513–560.

33. Kelly to Terrance F. Higgins, Dec. 8, 1942, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2408, file 56125/27-D, RG 85, NAB.

34. Schofield to All District Directors, Jan. 29, 1942, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2407, file 56125/27, RG 85, NAB.

35. Office of Censorship, "Report on the Development of United States Postal Censorship during Its First Year of Operation," pp. 145–148, historical file (Postal Censorship) 1934–1945, History of Postal Censorship, RG 216, NACP.

36. For the third edition, see "Regulations Governing the Censorship and Deposition of Prisoner of War and Interned and Detained Civilian Mail," June 14, 1944, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2406, file Postal Censorship Procedure Manual, RG 85, NAB.

37. "Report of Enemy Aliens in Temporary Detention," Dec. 31, 1942, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2410, file 56125/35, RG 85, NAB.

38. "Civilian Enemy Aliens and Prisoners of War," May 1942, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2403, file 56125/25-A, RG 85, NAB.

39. Provost Marshal General to Commanding Generals, All Service Commands, Sept. 17, 1942, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 11, file 56125/27-D, RG 85, NAB.

40. Office of Censorship, "A History of the Office of Censorship," Vol. 4, pp. 193-204, entry 4, box 2, RG 216, NACP.

41. Provost Marshal General to Commanding Generals, All Service Commands, Jan. 14, 1943, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2408, file 56125/27-D, RG 85, NAB.

42. E. J. Mattson, "History of Prisoner of War Unit: Chicago Postal Censorship Station," Sept. 24, 1942, Historical fFile (Postal Censorship), 1934–1945, box 1207, RG 216, NACP.

43. Bert Fraser to Postal Censor, Oct. 19, 1942, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2408, file 56125/27-D, RG 85, NAB.

44. Fraser to Kelly, Nov. 9, 1942, ibid.

45. Byron Price to Kelly, Jan. 20, 1943, ibid.

46. Kelly to Edward J. Ennis, June 1, 1943, ibid.

47. Memorandum from Kelly to Ennis, Nov. 13, 1943, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2408, file 56125/27-F, RG 85, NAB.

48. Ibid.

49. Memorandum from the Legation of Switzerland to the Secretary of State, Oct. 29, 1943, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2408, file 56125/27-E, RG 85, NAB.

50. Kelly to Officers in Charge Alien Internment Camps, Apr. 3, 1944, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2408, file 56125/27-H, RG 85, NAB.

51. Ibid.

52. Kelly to Officer in Charge, Crystal City, TX, Feb. 14, 1945, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, box 2409, file 56125/27-M, RG 85, NAB.

53. For a history of this highly decorated nisei unit, see Chester Tanaka, Go For Broke: A Pictorial History of the Japanese American 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (1982).

54. Byron H. Spinney to Officer in Charge, San Pedro Detention Station, Feb. 20, 1945, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, file 56125/27-M, box 2409, RG 85, NAB.

55. John M. Gibbs to Kelly, May 7, 1945, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, file 56125/27-O, box 2409, RG 85, NAB.

56. Fraser to Capt. Hartwell C. Davis, Oct. 11, Dec. 23, 1943, Field Records, Alien Enemy Internment Camps—Fort Missoula, file 1014/E (Cooperation—Bureau of Prison Officials), RG 85, NAB.

57. Gibbs to Kelly, Apr. 28, 1945, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, file 56125/27-O, box 2409, RG 85, NAB.

58. The literature on the loyalty questionnaire and the renunciants is extensive. See, for example, Dorothy S. Thomas and Richard Nishimoto, The Spoilage (1946, reprint 1969); and Donald E. Collins, Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and the Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans during World War II (1985).

59. U. B. Buchanan to Chief Postal Censor, Aug. 6, 1943, entry 1, box 61, File War Relocation Authority, RG 216, NACP.

60. Michi Weglyn, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps (1976, reprint 1995), p. 247.

61. For an account of the renunciants, see ibid., pp. 229–248.

62. McCoy to Kelly, Mar. 3, 1945, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, file 56125/27-M, box 2409, RG 85, NAB.

63. McCoy to Kelly, July 4, 1945, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, file 56125/27-O, box 2409, RG 85, NAB.

64. Radiogram, Ugo Carusi to McCoy, Aug. 17, 1945, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, file 56125/27-M, box 2409, RG 85, NAB.

65. Carusi to Officer in Charge, Aug. 17, 1945, accession 85-58A734, Central Records, file 56125/27-P, box 2409, RG 85, NAB.

66. Abner Schreiber to Kelly, Sept. 20, 1945, ibid.

67. Collaer to District Director, Los Angeles, Dec. 13, 1945, ibid.

68. Kelly to Abner Schreiber, Mar. 1, 1946, ibid.

69. J. L. O'Rourke to Kelly, July 8, 1946, ibid.

70. Kelly to Second Assistant Post Master General, Apr. 9, 1948, ibid.

71. According to a postwar accounting by the INS, 31,275 persons were received by the INS under the alien enemy program, including those received from outside the continental United States. See Kelly to A. Vulliet, Aug. 9, 1948, copy in Don Heinrich Tolzmann, ed., German-Americans in the World Wars, Vol. 4, sec. 1, pt. 1, (1995), p. 1513.