“Two Japans”

Japanese Expressions of Sympathy and Regret in the Wake of the Panay Incident

Summer 2001, Vol. 33, No. 2

By Trevor K. Plante

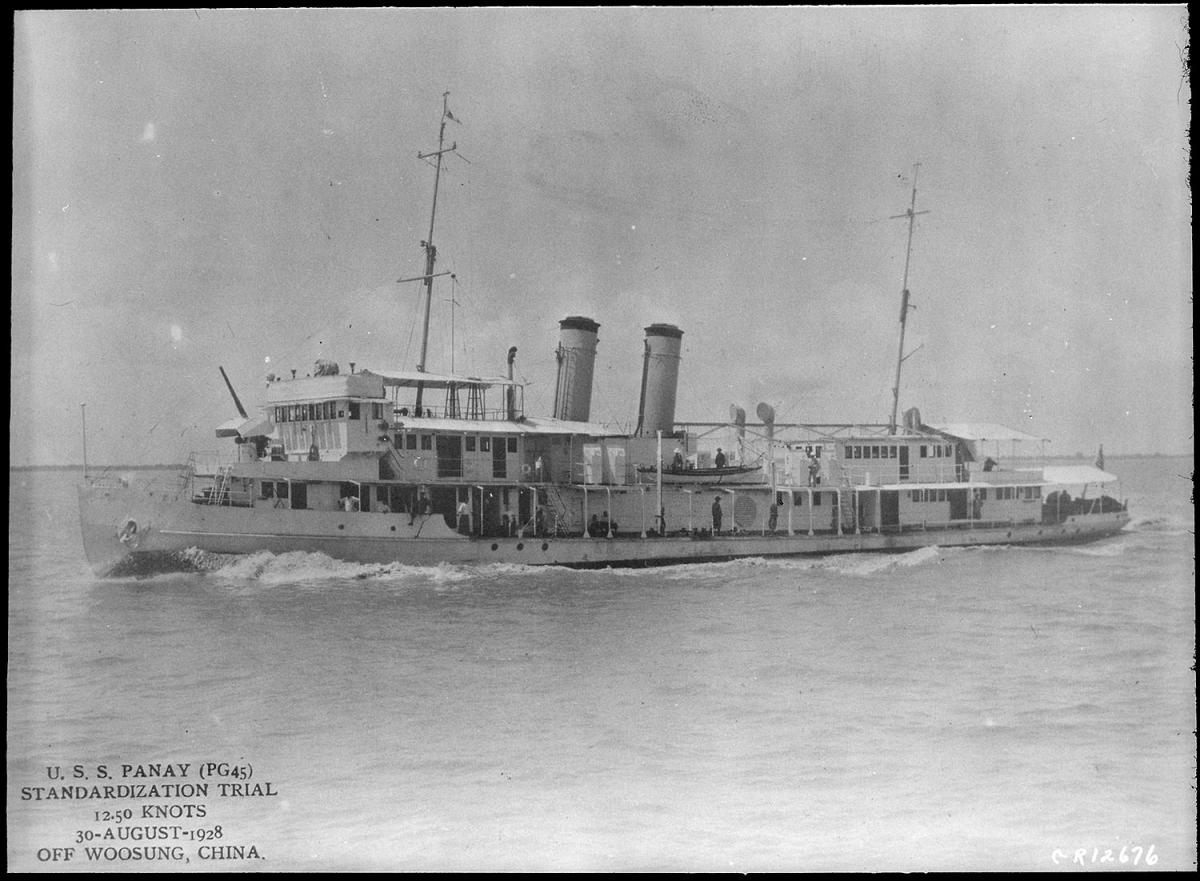

Four years before Pearl Harbor, the United States and Japan were involved in an incident that could have led to war between the two nations. On December 12, 1937, the American navy gunboat Panay was bombed and sunk by Japanese aircraft. A flat-bottomed craft built in Shanghai specifically for river duty, USS Panay served as part of the U.S. Navy's Yangtze Patrol in the Asiatic Fleet, which was responsible for patrolling the Yangtze River to protect American lives and property.1

After invading China in the summer of 1937, Japanese forces moved on the city of Nanking in December. Panay evacuated the remaining Americans from the city on December 11, bringing the number of people on board to five officers, fifty-four enlisted men, four U.S. embassy staff, and ten civilians. The following day, while upstream from Nanking, Panay and three Standard Oil tankers, Mei Ping, Mei An, and Mei Hsia, came under attack from Japanese naval aircraft. On the Panay, three men were killed, and forty-three sailors and five civilians were wounded. Survivors were later taken on board the American vessel USS Oahu and the British ships HMS Ladybird and HMS Bee.

It was a nervous time for the American ambassador to Japan, Joseph C. Grew, who feared the Panay incident might lead to a break in diplomatic ties between Japan and the United States. Grew, whose experience in the foreign service spanned over thirty years, "remembered the Maine," the U.S. Navy ship that blew up in Havana Harbor in 1898. The sinking of the Maine had propelled the United States into the Spanish-American War; Grew hoped the sinking of the Panay would not be a similar catalyst.2

The Japanese government took full responsibility for sinking the Panay but continued to maintain that the attack had been unintentional. The formal apology reached Washington on Christmas Eve. Although Japanese officials maintained that their pilots never saw any American flags on the Panay, a U.S. Navy court of inquiry determined that several U.S. flags were clearly visible on the vessel during the attacks. Four days before the apology reached Washington, the Japanese government admitted that the Japanese army strafed the Panay and its survivors after the navy airplanes had bombed it. The Japanese government paid an indemnity of $2,214,007.36 to the United States on April 22, 1938, officially settling the Panay incident.3

Immediately after the Panay bombing, a lesser known aspect of the story started to unfold. In the days following the Panay incident, Japanese citizens began sending letters and cards of sympathy to the American embassy in Tokyo. Ambassador Grew wrote that "never before has the fact that there are 'two Japans' been more clearly emphasized. Ever since the first news of the Panay disaster came, we have been deluged by delegations, visitors, letters, and contributions of money—people from all walks of life, from high officials, doctors, professors, businessmen down to school children, trying to express their shame, apologies, and regrets for the action of their own Navy." In addition, "highly placed women, the wives of officials, have called on Alice [Grew's wife] without the knowledge of their husbands." The ambassador noted, "that side of the incident, at least, is profoundly touching and shows that at heart the Japanese are still a chivalrous people." These signs of sympathy were expressed as the ambassador was receiving word of possible atrocities being committed by Japanese forces in China.4

While most letters of sympathy were sent to the embassy in Tokyo, a few were sent to the Navy Department in Washington, D.C. One noteworthy group of letters received by the navy was from thirty-seven Japanese girls attending St. Margaret's School in Tokyo. The letters, each written in English and dated December 24, 1937, extended their apologies for the sinking of the Panay. By coincidence, the girls' letters are dated the same day the Japanese government's formal apology reached Washington. The letters are very similar in content. The typical letter reads, "Dear Friend! This is a short letter, but we want to tell you how sorry we are for the mistake our airplane[s] made. We want you to forgive us I am little and do not understand very well, but I know they did not mean it. I feel so sorry for those who were hurt and killed. I am studying here at St. Margarets school which was built by many American friends. I am studying English. But I am only thirteen and cannot write very well. All my school-mates are sorry like myself and wish you to forgive our country. To-morrow is X-Mas, May it be merry, I hope the time will come when everybody can be friends. I wish you a Happy New Year. Good-bye."5

Some of the girls enclosed postcards of beautiful Japanese places and scenes, while others sent Christmas cards and holiday wishes. One girl included a drawing of a Christmas candle burning bright with holly at the bottom. Several of the girls included their ages, which ranged from around eight to thirteen. Many of the letters are written on intricately decorated stationery. Each envelope bears the identical address: "To the Family of the 'Paney' [sic] C/O U.S.A. Navy Department, Washington, DC U.S.A." While each letter seems to be penned individually, the envelopes appear to have been addressed by the same person, possibly their teacher.

Three months later, a naval officer sent a reply to the principal of St. Margaret's School, thanking the girls for the cards and letters. The officer noted, "The kind thoughts of the little girls are appreciated, and it is requested that you inform them of this acknowledgement."6 Although the girls' letters were addressed to the families of the Panay victims, it does not appear that they made it any further than the Navy Department.

Other letters from Japanese individuals and organizations contained gifts of money along with expressions of regret. These donations caused a problem for the Navy Department. One letter from ten Japanese men expressed their sympathy over the Panay incident and included a check for $87.19. The men claimed to be retired U.S. Navy sailors living in Yokohama, and the letter, written by Kankichi Hashimoto, stated that "this little monetary gift is the instrument through which we hope to be able to further convey our sympathy with the bereaved families of the members of the Panay." The navy returned the check but informed the gentlemen that the U.S. ambassador in Tokyo had received a number of similar letters and gifts and that a committee was being formed in Japan to accept such donations.7 The donors were almost back to square one. They had originally approached the American consulate in Yokohama to donate three hundred yen. The consular staff said that they could not accept the contribution and suggested donating the money to the Japanese government. The former sailors turned down this suggestion and chose instead to send their donation to the Navy Department in Washington.

After being turned down by the navy, Mr. Hashimoto approached the U.S. naval attaché at the American embassy in Tokyo with a check for three hundred yen. The attaché, Capt. Harold Bemis, informed Ambassador Grew that a Mr. K. Hashimoto had brought in a contribution from the Ex-U.S. Navy Enlisted Men's Association of Yokohama. Bemis further told the ambassador that Hashimoto requested that the names of the former sailors be withheld from the Japanese authorities and public. The donor feared that his group's motives might be misconstrued because of their connection with the U.S. Navy but had no objection to their names being published in the United States.8

Letters and cards of sympathy and apology continued to pour into the American embassy in Tokyo. Meanwhile, the increasing number of donations from several sources had the State Department scrambling to come up with a policy on how to handle the monetary gifts. Four days after the sinking of the Panay, Grew sent a telegram to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, presenting the problem and requesting advice. With cash donations coming into the embassy by mail and in person, the contributions were creating what the ambassador described as "a delicate problem." As Grew explained to Hull, "Cash donations to Americans in the disaster are being brought in or sent to the embassy and we hear that the newspapers and various Government departments are receiving donations for transmission to us." While the ambassador attempted to turn away many of the donors, he explained to the secretary of state, "On the other hand the donations are all of trivial amounts so that sentiment is chiefly involved in the problem and to return the donations might give rise to a misunderstanding of our attitude."9

Grew was concerned that accepting any money from the Japanese people might interfere with the official indemnity the Japanese government had already agreed to pay. Expressing his concern to Hull, he wrote, "We realize that the acceptance of the donations for the purpose for which they are offered might prejudice the principle of indemnification for which the Japanese Government has assumed liability." The ambassador was in a difficult position: accepting the money posed one set of problems, while refusing the contributions posed another. Grew did not wish to offend the contributors, explaining that "logical grounds for refusal are difficult to explain to people who know of no other way to express their regrets over the disaster." One suggestion offered in Grew's telegram was to accept the donations and give the money to the American Red Cross for relieving Americans in China. The ambassador ended the telegram by requesting the State Department's guidance on the matter as soon as possible.10

The Navy Department also dispatched a telegram to the State Department to inform them that the Japanese junior aide navy minister had presented the naval attaché in Tokyo with ¥650.11 that had been donated by several organizations and individuals. The Navy Department also included part of a dispatch from the naval attaché in which he informed them that "as this is but one of many popular expressions of public sympathy and concern manifested during [the] past three days and furthermore [it] is a Japanese custom which if not accepted by our government might lead to misunderstanding, it is recommended that same be accepted in the spirit in which offered."11 Similarly Adm. Harry Yarnell, commander of the U.S. Navy's Asiatic Fleet, was also offered a large sum of money by personnel of the Japanese Third Fleet but declined the offer.12

In a telegram of December 18, Secretary of State Hull replied to Grew, "In view of the apparent sincerity of feeling in which the donations are being proffered and of the likelihood that a flat rejection of such offers would produce some misunderstanding of our general attitude and offend those Japanese who make such a gesture, the Department is of the opinion that some method should be found whereby Japanese who wish to give that type of expression to their feelings may do so."13

One of the problems posed by the contributions involved the difficulty of the U.S. government accepting money. Hull explained that "the Department feels, however, that neither the American Government nor any agency of it nor any of its nationals should receive sums of money thus offered or take direct benefit therefrom." Hull suggested that Grew approach Prince Iyesato Tokugawa or another Japanese gentleman, "inquiring whether he would be willing to constitute himself an authorized recipient for any gifts which any Japanese may wish voluntarily to offer in evidence of their feeling, public announcement to be made of such arrangement and an accompanying announcement that funds thus contributed will be devoted to something in Japan that will testify to good will between the two countries but not be conveyed to the American Government or American nationals."

Prince Tokugawa was president of the America-Japan Society, which had been formed in 1917 to promote a better relationship and understanding between the people of Japan and the United States. The society was formed in Tokyo and included prominent leaders from various fields; Viscount Kentaro Kaneko was elected as the first president, and U.S. Ambassador R. S. Morris served as the first honorary president.14

From the beginning, the State Department's position was that none of the families of those killed or the sailors or civilians wounded would receive any of the contributions. Nor would any office or department of the federal government accept the money. The State Department also expressed the desire that any necessary arrangements be made promptly. Hull did not wish to keep the Japanese people waiting for a decision on what was to become of the money they donated. A prolonged delay could lead to misunderstanding, especially if a decision was reached months later to return the money to the donors.15

The State Department telegram of December 18 also set forth, at least for the time being, that only the American ambassador in Japan and the American ambassador in China could accept donations related to the Panay incident. Several American consulates were receiving money, including consulates at Nagoya, Kobe, Nagasaki, and Osaka, in Japan; Taihoku, Taiwan; Keijo (Seoul), Korea; Dairen, Manchuria; and São Paulo, Brazil.16 These contributions were eventually forwarded to the ambassador in Tokyo. Grew kept all money received related to the Panay incident in the embassy safe until the State Department could find a solution.

The American consulate in Nagasaki forwarded several contributions and translations of letters to the embassy in Tokyo, including fifty yen from a Mr. Ichiro Murakami, identified as a former U.S. Navy pensioner, and another individual who wished to remain anonymous.17

In a letter two days later, the consulate in Nagasaki also reported to Grew that on December 21 a small boy from the Shin Kozen Primary School brought in a letter and donation of two yen to the consulate and was accompanied by his older brother. The consul enclosed the contribution and both the original and translation of the boy's letter. The letter reads, "The cold has come. Having heard from my elder brother that the American warship has sunk the other day I feel very sorry. Having been committed without intention beyond doubt, I apologize on behalf of the soldiers. Please forgive. Here is the money I saved. Please hand it to the American sailors injured." The letter, addressed "To the American sailors," was signed only, "One of the pupils of the Shin Kozen." The boy did not provide his name in the letter, nor did he reveal it when visiting the consulate.18

A local newspaper, the Nagasaki Minyu Shimbun, published the story of Mr. Murakami's donation and that of the schoolboy and included an excerpt of the boy's letter. Arthur F. Tower, the American consul in Nagasaki, informed Ambassador Grew of the article, which had been published on January 7. Tower also informed Grew that a reporter of another newspaper, the Tokyo and Osaka Asahi Shimbun had called on him on December 23 to discuss the Panay contributions. Towers reassured Grew that "this consulate has not sought to give publicity to the donations received or offered and has furnished information concerning them on two occasions only, when requested."

Although the consul in Nagasaki was not trying to publicize the donations, the newspaper stories may have increased contributions at his consulate. On January 8 a Japanese pensioner of the U.S. Navy called in person to make a contribution of five yen for the relief of those involved in the Panay incident. When his contribution was accepted, the former sailor informed the consul that a group of other U.S. pensioners also wished to donate money. On January 10 he visited the consulate again, this time with two representatives of Japanese pensioners of the U.S. Navy who lived in the area. By this time, however, the Nagasaki consulate had received the consulate general's supervisory circular informing them that all Panay-related contributions were to be made either to the ambassador in China or the ambassador in Japan. The gentlemen attempted to donate money but were informed that the consul could no longer receive contributions, and the men were asked to communicate directly with the American embassy in Tokyo. Soon after the departure of the former U.S. sailors, two Japanese men arrived at the consulate. These gentlemen, representing the Buddhist Association of Nagasaki, also had come to donate money for victims of the Panay and were likewise turned away.19

The American consulate in Capetown, South Africa, forwarded a contribution for the "Panay disaster fund" from twenty Japanese schoolchildren traveling on the M.S. Buenos Aires Maru from Japan to Brazil. Mrs. H. MacSwiggen of Los Angeles, California, had presented an envelope addressed to the American consul on January 3, 1938. The envelope contained a letter and $7.50 in U.S. currency.20

On January 6, 1938, the consul in Harbin, Manchuria, forwarded five yen along with a translated letter "signed by an unidentifiable person called 'KIYOKO.'" Kiyoko's letter states,

"We are really sorry to think that our absolutely trusted military should have made the blunder. We only pray that this sort of thing will never again be caused by the Japanese, who fight only for the sake of peace." The donor expressed sympathy for the Panay incident, adding, "When we think of the victims of the incident, words fail to express our deep regret."21

Ambassador Grew also received the following poem translated into English:

Beguiled by the rough mischievous waves

And Amid the din and turmoil of the battle,

The heroes of the air, eager to chase the fleeing foe.

Bombed, alas! By mistake, a ship not of the enemy,

But of the friendly neighbor country, which sank

with a few sailors aboard.

The source of nation-wide grief, which knows no bounds,

That fatal missile was.22

In a letter to Admiral Yarnell, Ambassador Grew shed light on his feelings about the donations and the general situation.

As for the civilian population, I have been really touched by the depth and genuineness of the feeling of shame in which has been expressed to me in countless visits and letters from people in all walks of life. The donations for the survivors and the families of the dead already amount to more than fifteen thousand yen, but this sum will be turned over to some Japanese individual or organization to devote to some constructive purpose in the interests of Japanese-American friendship as our Government does not wish it to go to any American nationals. Nevertheless, I cannot for a moment look into the future with any feeling of confidence. I do not think that our Government or people would be willing to go to war to protect our tangible interests in China, but I do think that some act constituting a derogation of American sovereignty, or an accumulation of affronts such as the Panay incident, might well exhaust the patience of both our Government and people and might place us in a position where war would become inevitable.23

While letters and contributions were forwarded to Tokyo, Grew was still attempting to come up with a solution to his "delicate problem." Embassy staff did not write letters acknowledging or thanking donors unless people wrote inquiring if the embassy had received their contributions. In these cases, staff informed the donors that the embassy was holding the money until a determination could be reached on the final disposition of the donations.

Meanwhile, in a January 14 telegram to Hull, Grew informed the secretary of state that Prince Tokugawa was waiting for several leading Japanese to return to Tokyo so that he could confer with them on the Panay contribution problem. Grew added that to date there was almost five thousand dollars in the Panay fund but that "contributions have almost ceased."24

On January 20 Prince Tokugawa met with his advisers, and they recommended that he not accept the money or set up a committee under the guidelines set forth in the State Department telegram of December 18. The next day, Grew sent a telegram to Hull stating that Tokugawa's advisers "feel certain that if the money were to be taken over by him under the conditions laid down by the [State] Department the contributors would strongly resent the diversion of the contributions from the object for which they were made, namely, to help those who suffered from the attack on the Panay." Grew informed the State Department that he felt there were now only two alternatives: first, return the contributions to the donors, an option "against which I strongly recommend"; second, "that there be simultaneously a nominal acceptance of the fund by the PANAY survivors and a contribution by the survivors in their turn of the fund to some deserving project in Japan." As a sign of Grew's growing frustration, the ambassador closed his telegram, "Should insurmountable legal difficulties stand in the way, would the Department be disposed to recommend Congressional action?"25

This telegram was sent at 7 p.m. The ambassador sent another telegram an hour later "For the Secretary personally." Grew expressed his hope to Hull that the previous telegram would "have your own direct consideration." The ambassador stressed, "The issue involved seems to me of prime importance and I feel that much depends on the Department's favorable decision. Should these funds have to be returned to the donors the Embassy, through no fault of its own, would be placed in a most difficult and embarrassing position and I fear that the resulting reaction on Japanese public opinion, owing to the probably widespread publicity, would be very unfortunate." Again the ambassador was making it clear how unsavory the possibility of returning the contributions would be. "I think that especially at this time of military depredations we should do our best to retain the sympathy of the Japanese public and that to return these donations to the contributors would very likely cause resentment throughout the country against the United States."26 The military depredations to which Grew was most likely referring were taking place in China.27

Hull responded to Grew two days later: "The Department . . . finds itself confronted with serious difficulties in reaching a decision owing to the lack of clear indication as to what was in the minds of the donors." Hull further explained that it was unclear if the contributions were intended for those killed, or the survivors, for both civilians and government personnel, and if the donations were to be distributed equally among all those involved in the incident or proportionately depending upon loss. Hull suggested approaching Prince Tokugawa again or another Japanese leader to help in "interpreting the spirit of the donors collectively in regard to the allocation of the funds."28

With these questions in mind, Grew contacted Prince Tokugawa, asking for insight into the intent of the Panay donors. On January 28 Mr. Yenji Takeda, manager of the America-Japan Society, visited the American embassy in Tokyo and requested a list of donors or representative groups that had made large contributions to the Panay fund. Takeda informed the embassy staff that a special committee was being formed as requested by the ambassador to determine the intentions of the contributors. A member of the embassy staff, a Mr. Pyle, chronicled Takeda's conversation. Takeda indicated that he did not think a committee was necessary because "he felt that in most cases the donors did not have any concrete idea when they gave the money as to how it should be used, and that they intended to leave this question to the discretion of the Ambassador." As explanation, "he referred to the Japanese custom by which when a misfortune happens to some one, even though he may be rich, his friends send gifts of money simply to express their sympathy. . . . This money is then used for flowers or for whatever purpose the recipient thinks is best."

Pyle further recorded that "Mr. Takeda stressed the idea that money of this sort was not given for charity, but that the gift of money was the customary way to express sympathy. In view of this Mr. Takeda said that he saw no reason why this fund could not be disposed of in any way that the Ambassador thought best, and that it was understood in such cases that the money could be used for charity or any other worthy purpose." Perhaps the most important insight provided by Takeda was to point out "that the only real obligation under these circumstances was to accept the money, as a refusal to do this was considered to be a serious rebuff."29 This was the situation that Grew had dreaded from the beginning. The last thing the ambassador wanted was to return the Panay contributions, thereby offending the Japanese donors.

Ambassador Grew soon received reassuring news. Prince Tokugawa and his committee of advisers met on February 8 to discuss the Panay contributions and passed the following resolution: "That the contributions were made for the purpose of manifesting the sympathy of the Japanese people toward those persons who were wounded and the families of those persons who were killed on board the United States gunboat Panay and the three American steamships on December 12, 1937, during the Japanese military operations on the Yangtze River directed at [the enemy?], and in consequence of attacks mistakenly made by the Japanese forces; and that the disposal of such contributions in keeping with the original purposes for which they were made shall be left entirely to the discretion of His Excellency, the American Ambassador, Mr. Grew."30 This was welcome news for Grew. The ambassador now only needed State Department approval, but more important, it was beginning to look as though the money would not have to be returned to the donors.

Hull dispatched a telegram to Grew on February 12, reminding the ambassador of the State Department opinion, "in which the Navy Department concurred," that neither the American government nor any agency of it nor of its nationals should benefit and declaring that "the Department desires that you proceed along the lines indicated in paragraph four of your 46, January 21, 7 P.M. if in your judgment such a course will best dispose of the matter and be satisfactory to the Japanese government."31 The paragraph cited is from Grew's January 21 telegram, which suggested sending a nominal amount to the survivors and using the rest of the contributions for a deserving project in Japan. While restating that no Americans would benefit from the contributions, the State Department was suggesting in a roundabout way that the money be used for a project in Japan.32 On February 22, the secretary of state sent a telegram to the ambassador in China requesting him to forward any Panay contributions received by him to the ambassador in Tokyo.33

Although Grew reported in an earlier telegram to the State Department that contributions were falling off, it is unclear how much they were really slowing down since the America-Japan Society was still collecting money. Prince Tokugawa wrote to Grew in February that the America-Japan Society in Tokyo had already amassed ¥16,242.56 in Panay contributions from 7,749 people and 218 organizations. Tokugawa wrote, "We should be most happy and grateful if through Your Excellency's good offices this material expression may be transmitted to those who suffered injuries on the 'Panay' and on the other American ships, as well as to the bereaved families of those who met with death at the time." Tokugawa was keeping to the original intent of the contributors but added, "We would ask you to dispose of the fund in any manner which in your good judgement may seem in keeping with the sincere desire of the contributors."34 Tokugawa also included a list of organizations that donated money to the Panay fund with his letter.

Grew's task now was to find a suitable project in Japan for the Panay fund. The ambassador offered several suggestions in a telegram to the State Department, including endowment of beds in a charity hospital, endowing a scholarship for Japanese graduates of the American school in Tokyo to continue their studies in the United States, giving money to the English Speaking Society of Japan, founding a Townsend Harris memorial museum, or endowing a special section of a library in Japan for acquiring American publications, particularly American government publications.

Grew candidly stated that he did not favor any of these suggestions. Instead, the ambassador preferred that the contributions be held in perpetuity under a trust in Japan known as the America-Japan Trust. Grew proposed that the trustees be the American ambassador, the Japanese president of the America-Japan Society, and one other American to be nominated by the trustees. Money from the fund would be used in accordance with the principle of the State Department's December 18 telegram, that is, to promote good will between Japan and the United States but not to directly benefit the American government or its nationals.

In a March 2 telegram to Ambassador Grew, the secretary of state suggested "that the proposed American-Japan trust be so constituted as to have a wider scope than to serve exclusively as a repository for the PANAY contributions." Hull closes the telegram informing the ambassador that, "You should of course be careful to avoid giving any encouragement to the suggestion for an increase in the PANAY contributions."35

Two weeks later Ambassador Grew received a memorandum from a "CC," presumably Charles R. Cameron, American consul general in Tokyo. Cameron advised Grew that if Prince Tokugawa proposed increasing the Panay contributions, the ambassador should discourage it. Reminding Grew that the State Department made it clear that "we should do nothing to encourage such an increase," Cameron suggested that any increase to the trust fund should come at a later time and not be associated with the Panay contributions. Cameron added, "The hope is certainly that this trust will outgrow its connection with that incident." It was the consul's belief that "The popular expression of sentiment embodied in the Panay contributions served its important purpose, but the increase of the sum by a few large donations would not in any way increase the importance of that expression of sentiment."36

In a March 17 telegram to the State Department, Ambassador Grew forwarded several enclosures, including a copy of the proposed articles of incorporation for the Japan-America Trust, a proposed letter to the trustees from Grew, and a proposed letter to the contributors from the ambassador to be translated into Japanese. Article one of the articles of incorporation named the proposed organization the Japan-America Trust (Nichibei Shintaku). Article two proposed that "The object of this trust shall be to use in Japan, for purposes testifying to good will between Japan and the United States, such funds as may be entrusted to it." Other articles set forth that the trustees be the American ambassador to Japan, the Japanese president of the America-Japan Society, and an American resident in Japan nominated by the first two trustees. The trustees would meet on the second Tuesday of November every year, and the office of the trust would be the office of the America-Japan Society. According to the last article, "If, while there are assets remaining, the trustees fail throughout two successive calendar years to meet and act toward disposition of the capital fund or revenue, the residue of the trust shall vest in the Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Japanese Government for use in accordance with the purpose of the trust."37

State Department approval of the proposals came April 9, and a trust fund was created in Japan to handle the Panay contributions.38 On April 19, 1938, the American embassy in Tokyo issued a statement to the press announcing the creation of the Japan-America Trust, which was being endowed in the name of the Panay survivors and relatives of those who lost their lives. The press release clearly stated that the Panay contributions were in no way related to the official settlement between the two nations but that "the donors have simply sought to express their sympathy by a procedure which is common in Japanese custom."39

The announcement appeared the following day in the Japan Advertiser. The English-language newspaper reported the amount of the fund at thirty-seven thousand yen with contributions from eight thousand sympathizers. The paper also reported that the fund would be administered by Ambassador Joseph C. Grew and Prince Iyesato Tokugawa, president of the America-Japan Society, with a third trustee nominated by them later.40 The third trustee selected was Bishop Charles S. Reifsnider. Grew proposed Bishop Reifsnider for the position in a letter to Tokugawa on April 12, and the prince concurred two days later.41

According to the article, embassy officials explained that the Japan-America Trust would be similar to the Pilgrim Trust Fund established in London for the repair of old monuments having American associations. Most likely, according to the paper, the Japan-America Trust would be used for the care of graves of American sailors buried in Japan.

The embassy prepared a form letter signed by Ambassador Grew to send to donors to acknowledge their contributions and inform them of the establishment of the Japan-America Trust. Grew expressed his "hope and belief that the Japan-America Trust, receiving its original impulse from the feeling of sympathy with which the news of the PANAY incident was met in Japan, will become and remain an important foundation in the maintenance of friendship between the people of Japan and the people of the United States, appropriately symbolizing the generous feeling which has been manifested." The Foreign Office in Tokyo after learning of the establishment of the Japan-America Trust, felt it was up to the Japanese people to make the fund as large as possible.42

On May 9, Prince Tokugawa wrote to Grew, "It is gratifying to me that the spirit which prompted the Japanese contributors is understood by your people and that the same spirit of sympathy and friendship has resulted in the establishment of this trust fund." Tokugawa closed the letter, "I am sure that this Japan-American Trust which is now being established will long remain a symbol of friendship between the peoples of Japan and the United States."43

Following up on the trust fund's proposed project, the naval attaché in Tokyo, Capt. Harold Bemis, wrote to the Navy Department's Bureau of Medicine and Surgery on June 10, 1928, requesting a list of cemeteries or burial plots of U.S. naval personnel interred in Japan. An officer at the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery responded that such a list had been prepared in 1929 and forwarded the report. The report listed the names of U.S. sailors and marines buried at the following cemeteries: Foreign Cemetery in Yokohama; Kakizaki, Shimoda; Ono Cemetery, Nagasaki; Urakami Cemetery, Nagasaki; Hakodate, Hokkaido; Ono Cemetery in Kobe; and Naha, Loochoo Island (Southern Okinawa).44 The names listed for Naha included seven sailors from the Perry expedition, the first American contact with Japan in 1853 - 1854. By coincidence, Ambassador Grew's wife, the former Miss Alice de Vermandois Perry, was a descendant of Commodore Oliver Perry.45

In the end, both sides appeared relieved with the outcome of the Panay contributions problem. The establishment of the Japan-America Trust removed any need to return the money, and no part of the U.S. government or any American national benefited from the donations. A search of State Department records as well as Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Ten Years in Japan, Turbulent Era, and Grew's biography did not furnish the information on the final disposition of the trust. It is possible that further research might provide the answer.

Ambassador Grew's description of the events after the Panay incident as demonstrating "two Japans" is very insightful. As the Japanese people expressed sympathy and regret through letters, cards, visits, and contributions, the ambassador was receiving telegrams of maltreatment of Chinese citizens and American citizens and property by Japanese military forces in China. While actions by Japanese forces in China strained relations between America and Japan, letters sent in the aftermath of the Panay incident expressed sincere hope that the two nations would remain friends. Two Japans indeed.

Trevor K. Plante is an archivist in the Old Military and Civil Records unit, National Archives and Records Administration. He specializes in U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps records prior to World War II.

Notes

The author would like to thank Rebecca Livingston of the National Archives and Records Administration for showing him the letters from St. Margaret's School in the navy records; it was the genesis of this piece. The author would also like to thank NARA archivists Richard Peuser and Kenneth Heger for their helpful suggestions with other NARA records.

1. Hamilton Darby Perry, The Panay Incident: Prelude to Pearl Harbor (1969), p. 4; and Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Vol. 5 (1970), pp. 208-209.

2. Joseph C. Grew, Ten Years in Japan (1944), p. 235. For more information on Grew's foreign service, see Waldo H. Heinrichs, Jr., American Ambassador: Joseph C. Grew and the Development of the United States Diplomatic Tradition (1966).

3. The published findings of the U.S. Navy court of inquiry can be found in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States: Japan: 1931 - 1941, Vol. 1 (1943), pp. 542–546. On December 20, 1937, the Japanese government admitted the machine-gun attacks by the army in strafing the Panay. For more information from the Japanese perspective see Masatake Okumiyo, "How the Panay was Sunk," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 79 (June 1953): 587–596.

4. Grew, Ten Years in Japan, p. 236.

5. Tadako Oka to Navy Department, PR5/L11-1 (380311), box 3860, entry 22, General Records of the Department of the Navy, 1798–1947, Record Group (RG) 80, National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, DC.

6. Capt. O. M. Hustvedt to Principal of St. Margaret's School, Mar. 11, 1938, ibid.

7. Kankichi Hashimoto to Navy Department, Dec. 28, 1937, and Navy Department to Hashimoto, Jan. 18, 1938, PR5/L11-1 (37212), box 3860, entry 22, RG 80, NAB. See also letters from Kankichi Hashimoto, Dec. 28, 1937, and American Consul Yokohama, Dec. 29, 1937, found in 394.115 Panay/315, box 1851, Central File, 1930–1939, General Records of the Department of State, RG 59, National Archives at College Park, MD (NACP).

8. Memo, Feb. 25, 1938, box 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, U.S. Embassy in Japan, Post Files, Records of Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, RG 84, NACP.

9. Grew to Secretary of State, Dec. 16, 1937, telegram 645, box 19, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, U.S. Embassy in Japan, Post Files, RG 84, NACP.

10. Ibid.

11. Naval attaché dispatch quoted in William D. Leahy to Secretary of State, Dec. 17, 1937, PR5/L11-1 (37212), RG 80, NAB. See also Telegram Received from ALUSNA, Dec. 16, 1937, 394.115 Panay/125, box 1851, Central File, 1930–1939, RG 59, NACP.

12. State Department to Embassy in Tokyo, Dec. 18, 1937, telegram 361, box 19, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

13. Ibid.

14. From www.us-japan.org/ajs/ web site for America-Japan Society Inc. Currently the society is the America-Japan Society Inc. located in Tokyo, Japan. There are also several America-Japan Societies in Japan and Japan-America Societies in the United States.

15. State Department to Embassy in Tokyo, Dec. 18, 1937, telegram 361, box 19, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

16. Letters from consulates found in boxes 19 and 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

17. Arthur Tower, American Consul, Nagasaki, Japan, to Grew, Dec. 21, 1937, box 19, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

18. Tower to Grew, Dec. 23, 1937, ibid.

19. Tower to Grew, Jan. 11, 1938, box 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

20. James Orr Derby, American Consul, Capetown, South Africa to Arthur Garrels, American Consul General, Tokyo, Jan. 10, 1938, ibid.

21. George R. Merrell, American Consul in Harbin, Manchuria to Grew, Jan. 6, 1938, ibid.

22. Grew, Ten Years in Japan, pp. 241–242.

23. Grew to Adm. H. E. Yarnell, Jan. 10, 1938, quoted in Joseph C. Grew, Turbulent Era: A Diplomatic Record of Forty Years, 1904–1945, ed. Walter Johnson, 2 vols. (1952), pp. 1204–1206.

24. Grew to Secretary of State, Jan. 14, 1938, telegram 27, box 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP. In a previous letter, on behalf of Secretary of State Hull, Grew thanked Tokugawa for his expression of regret over Panay incident. See Grew to Tokugawa, Dec. 17, 1937, 394.115 Panay/269, box 1851, Central File, 1930–1939, RG 59, NACP.

25. Grew to Secretary of State, Jan. 21, 1938, telegram 46, box 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

26. Ibid., telegram 47.

27. For more information on depredations by Japanese forces in China, see telegrams published in Foreign Relations and Iris Chang, The Rape of Nanking (1997).

28. Hull to Grew, Jan. 23, 1938, telegram 23, box 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

29. Report of conversation between Mr. Takeda and Mr. Pyle regarding the PANAY fund, Jan. 28, 1938, ibid. Mr. Takeda's full name and title is found in a February 23, 1938, letter, ibid.

30. Foreign Relations, pp. 556–557. The bracketed text appears in the original source and was not added by the author.

31. Hull to Grew, Feb. 12, 1938, telegram 57, box 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

32. Refers to Grew to Secretary of State, Jan. 21, 1938, telegram 46, ibid.

33. Hull to Embassy Peiping, China, to be repeated to Ambassador at Hankow, Feb. 22, 1938, telegram 53, ibid.

34. Tokugawa to Grew, February 1938, ibid.

35. Hull to Grew, Mar. 2, 1938, telegram 73, ibid.

36. Memo from CC to Mr. Ambassador, Mar. 17, 1938, ibid.

37. Grew to Secretary of State, Mar. 17, 1938, despatch No. 2811 with enclosures, ibid.

38. Hull to Grew, Apr. 9, 1938, telegram 126, ibid. The telegram approved of despatch 2811 and had only a few suggestions related to the draft letter to be sent to contributors.

39. Statement to the press by the American embassy in Tokyo, Apr. 19, 1938, ibid.

40. Naval Attaché Report, Tokyo, Apr. 20, 1938, Serial No. 84, #22462, C-8-C, box 438, entry 98, Intelligence Division, Naval Attaché Reports, 1886 - 1939, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, RG 38, NAB.

41. Grew to Tokugawa, Apr. 12, 1938, and Tokugawa to Grew, Apr. 14, 1938, box 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

42. Naval Attaché Report, Tokyo, Apr. 20, 1938, Serial No. 84, #22462, C-8-C, box 438, entry 98, RG 38, NAB. Grew to Sec. State, Apr. 29, 1938, telegram 257, quotes Foreign Office reaction, box 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, RG 84, NACP.

43. Tokugawa to Grew, May 9, 1938, box 42, 310/American Citizens Nanking/PANAY Fund, General Classified Files, RG 84, NACP.

44. Letter dated June 10, 1928, from naval attaché in Tokyo to Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (via ONI), letter, response, and list all found in P6-6/EF37 (61 & 62), box 165, entry 15A, General Correspondence, Jan. 1926 - Dec. 1941, Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, RG 52, NAB. Capt. Harold M. Bemis was naval attaché to the embassy in Tokyo from September 1, 1936, to May 11, 1939.

45. Heinrichs, Jr., American Ambassador, p. 9. Commodore Matthew C. Perry led the expedition to Japan in 1853–1854. He was Commodore Oliver H. Perry's younger brother. Eight sailors from the expedition were buried at Naha, but the report lists only seven names.