Honoring Our War Dead

The Evolution of the Government Policy on Headstones for Fallen Soldiers and Sailors

Spring 2003, Vol. 35, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By Mark C. Mollan

I do not believe that those who visit the graves of their relatives would have any satisfaction in finding them ticketed or numbered like London policemen or convicts.

—Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs, Report to the Honorable John Coburn, Chairman, Senate Committee of Military Affairs, January 9, 1872.

But if he finds his . . . ancestor's name and position in full therein inscribed he will be satisfied that a grateful country had done due honor to the soldier whose sacrifice is one of the proud recollections of his family history.

—General Meigs, Memorandum, Quartermaster General's Office, February 8, 1873

Montgomery C. Meigs keenly understood the mood of a nation nursing the tender scars of war. As quartermaster general of the Union army, Meigs had choreographed and directed the supply lines that fed, clothed, and armed the largest army in the world for the duration of the bloodiest conflict in American history. As a father, Meigs mourned the loss of his eldest son, Lt. John R. Meigs, who died while on a scouting mission near Kernstown, Virginia. Meigs never fully recovered from his loss, but he found some solace in solemnly laying his son to rest in the newly established national cemetery at Arlington, Virginia.

With similar tenderness and attention, Meigs directed a program that laid to rest hundreds of thousands of fallen soldiers scattered on former battlefields throughout the South and became the genesis of our national cemetery system. Quartermaster deputies under Meigs's command scoured the landscape of the South to locate, unearth, and identify the remains of soldiers that lay in the former battlefields and prison and hospital yards stretching from Maryland to Texas. By 1870, the remains of nearly 300,000 soldiers had been buried in seventy-three national cemeteries. Although temporary wooden headboards were first used to mark the graves of the deceased, Meigs, with his usual diligence, saw to it that by 1879 each fallen veteran, known and unknown, would be "done due honor" with a proper permanent marker at the head of his grave.

The records of headstone applications, found in several different record series, are a minor legacy of the latter phase of Meigs's reinterment program but can prove valuable to researchers and genealogists. In addition to providing the final resting place of a fallen soldier or veteran, headstone applications sometimes include previously undiscovered evidence regarding an ancestor's military career or may point to other sources that hold information of interest to sleuths of family history. Information regarding burial locations of U.S. (and Confederate) veterans are manifest in scores of records series at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). An exhaustive description of all of these series is beyond the scope of this article. However, the following should provide some understanding of the beginnings of the government-provided headstone and offer the reader a starting point in locating an application.

Beginnings of the Government-Provided Headstone

After the disastrous outcome of the First Battle of Bull Run (Manassas) in July 1861, it became clear to many in the War Department that America's Civil War would last long past Christmas. The department anticipated a flood of inquiries on the status of loved ones and issued General Order 75, which pointed out the importance of "preserving accurate and permanent records of deceased soldiers and their place of burial" and decreed that "whenever any soldier or officer of the United States Army dies, it shall be the duty of the commanding officer of the military corps or department in which such person dies, to cause the regulation and forms provided [by the] Quartermaster General to be properly executed."

The following April, a similar order called for commanders to provide interment to fallen soldiers near every battlefield "so soon as it may be in their powers." The loose language of the order coupled with the burdens of battle ensured diligent compliance from few field commanders. Battle-weary Union soldiers were scarcely available to leave their duties at the front to identify and care for the dead. Additionally, high Union casualties throughout the war kept commanders concerned about low morale, lest desertion become an even greater problem. It was therefore left to the Office of the Quartermaster to care for deceased military personnel.

Such responsibilities were a natural development of traditional quartermaster duties. Since 1775, post quartermasters had been responsible for administering post burial grounds by supplying materials, including wooden headboards, and keeping records.

By 1865, a strengthened federal government empowered the Office of the Quartermaster General with the resources necessary to lay to rest the hundreds of thousands of recent war dead. On July 3, 1865, Meigs called upon his field officers to report on the interments recorded during the course of the war. Amid the louder calls for the expedient dissolution of the army and navy (including his own Quartermaster Department staff) and the liquidation of excess military materiel, Meigs's requests went largely unanswered. Forced to reissue similar orders on February 13, 1866, Meigs urged compliance with the order because it was

the intention of this Department that . . . the cemeteries of all Union soldiers and of all prisoners of war shall be inclosed with plain but substantial fences, and the graves of each marked with a head-board, plainly bearing a number, and the name, company, regiment, and State of each man, so far as can be ascertained.

Furthermore, the department intended to "publish a record of the names and place of interment of all soldiers who have perished in the service of the United States during the war."

Accomplishing the task of identifying all the remains and interring them in newly established cemeteries, was not only daunting but elusive. A survey of remains from the battlefields of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House identified only 1,500 of the 5,350 fatalities. The rest of the fallen have never been identified.

In answer to Meigs's call for reports, Assistant Quartermaster James Moore wrote of the condition in which the Union dead were found at the battlegrounds of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania:

It was no unusual occurrence to observe bones of our men close to the abatis of the enemy; and in one case several skeletons of our soldiers were found in their trenches.

At both battle sites, Moore witnessed:

Hundreds of graves on these battlefields are without any marks whatever to distinguish them, and so covered with foliage that the visitor will be unable to find the last resting place of those who have fallen until the rains and snows of winter wash from the surface the light covering of earth and expose their remains.

However, even after locating the bodies of the deceased, there was often no means of identifying the body.

Like Moore, after visiting each battlefield or former prison yard throughout the South and border states, quartermaster personnel would report to the quartermaster general about the findings of each location, including as much information about the deceased as possible. After further research was completed using the War Department records, the reports were then published in a set of twenty-seven volumes, which provide the burial location of soldiers and sailors, the rank, regiment and company or ship, name and location of the cemetery of burial, and the grave number. With these, family and friends could search for the names of veterans to find their final resting place. Today, people still use the compiled reports, known simply as the "Roll of Honor," to find burial locations of ancestors. A published index provided by the Genealogical Publishing Company in 1995 facilitates the search. However, even at the time of publication, quartermaster personnel knew that the lists were plagued with clerical errors, misspellings, and other mistakes. Present-day researchers should consider the Roll of Honor a starting point but then try to confirm the information from other sources.

Despite the efforts of the quartermaster personnel, of the 300,000 remains reinterred, only 58 percent were identified. All graves, however, were marked with a wooden headboard according to the mandate detailed in General Order 75. With the reinterment program complete, attention soon turned to permanent markings for their graves. Public sentiment, though important, was not the sole factor driving the efforts for permanent markers. Economy also played a role. The average cost for a wooden headboard with a life span of five years was $1.55. After only ten years, the cost of the headboards, with some additional incidental expenses, would cost nearly one million dollars.

On February 22, 1867, Congress passed an act to "establish and to protect national cemeteries," a section of which called on the secretary of war to "cause each grave to be marked with a small headstone or block." Some proposals, based on economy, called for metal markers, either with full names or simply numbers. Meigs sided with those advocating marble or granite headstones marked with the names of the decedents.

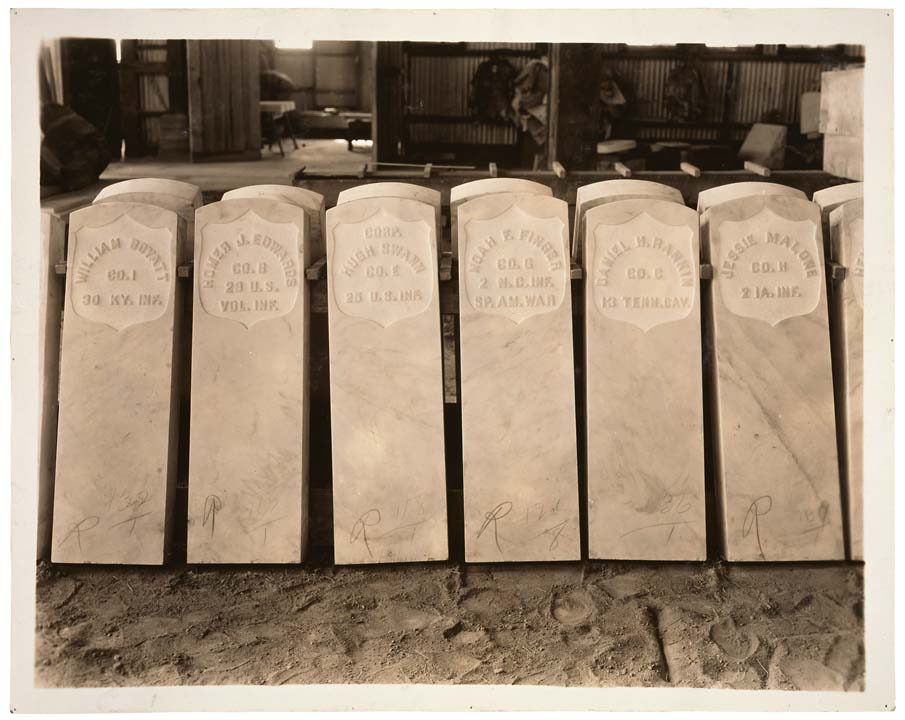

On March 3, 1873, Congress appropriated a million dollars to replace the headboards with markers of "durable stone" and allowed the secretary of war to determine "the size and model for such headstones, and the standards of quality and color of the stone to be used." The secretary specified white marble or granite; these stone slabs were cut to four inches thick, ten inches wide, thirty-six inches long for cemeteries south of Washington's latitude, and forty-two inches long for the more northerly latitudes. All headstones would reveal twelve inches of headstone after installation. The face would display a sunken shield carrying the number of the grave, rank, name of soldier, and the name of home state. For unknown soldiers, a block six inches square by thirty inches long would bear only the grave number.

The quartermaster general's 1878 annual report stated that all but 135 graves at the cemetery at Finn's Point, New Jersey, were marked by granite or marble headstones. In all seventy-nine national cemeteries, 165,102 markers were fully inscribed, while 145,841 graves were marked with the simple block markers. Because these markers were provided for graves by mandate of Congress, no record series of applications exist. The Roll of Honor serves as the best source for finding burial locations for these soldiers. Characteristic of the diligence of the quartermaster's office under the stewardship of General Meigs, $191,988 remained unspent from the original headstone appropriation. The bulk of these excess funds would provide the opportunity to expand the headstone program beyond the walls of the national cemeteries.

Two pieces of legislation championed by the Grand Army of the Republic, a powerful Civil War veterans organization, greatly amplified the headstone program beyond its original scope. First, under the terms of a supplemental appropriations bill passed by Congress on March 3, 1873, all "honorably discharged soldiers, sailors, or marines, who have served during the late war either in the regular or volunteer forces, dying subsequent to the passage of this Act, may be buried in any national cemetery of the United States free of cost, and their graves shall receive the same care and attention as those already buried." The GAR pressure, and the concern that the national cemeteries would quickly fill up, further expanded the scope of the program through legislation of February 3, 1879, "An Act authorizing the Secretary of War to erect headstones over the graves of Union Soldiers who have been interred in private, village, or city cemeteries." This legislation, later revised to include all military veterans, started the headstone application program that continues today.

Headstone Applications

Early headstone applications are found among the records of the Cemetery Branch, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General (Record Group 92). The Cemetery Branch created numerous record series dealing with headstones and other burial issues, but the headstone applications for private cemeteries are the most complete and extensive. The place to start is the Card Records of Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, ca. 1879–1903 (entry 628).

The Quartermaster General's Cemetery Branch created three-by-four-inch cards to keep track of the headstones ordered mostly for soldiers who died between 1861 and 1903. Because some relatives of veterans of previous wars applied for and received headstones, records of headstones for veterans of earlier wars, including the Revolutionary War and War of 1812, are scattered throughout the collection of the 166,000 cards. The cards record the name, rank, company, and regiment or vessel of the veteran (both army and navy), the name and location of the cemetery, the date of death, the company that supplied the headstone, and the date of contract. The cards are arranged alphabetically and have been filmed as a microfilm publication, Card Records of Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, ca. 1879–1903, M1845 (22 rolls), which is available in NARA research rooms in Washington, D.C., and the regional archives.

The next two series of records dealing with headstone applications, although more difficult to navigate, offer more details to the diligent researcher. The Applications of Headstones in Private Cemeteries, 1909–1924 (entry 592), and Applications for Headstones for Soldiers Buried at Soldiers' Homes, 1909–1923 (entry 591), were often completed by superintendents of those cemeteries on behalf of the survivors of the veteran. Although the official starting year of the applications is 1909, many applications were submitted for veterans already buried in cemeteries who, for varying reasons, had never received a headstone. Like the card records, applications can also be found for veterans of earlier conflicts, including the Revolutionary War. Examples of duplicate records in the Carded Records and the Headstone Application files are extremely rare, so be sure to examine both types of records.

The basic information on the applications is similar to the card records: name of veteran, rank, company, regiment or vessel, date of death, the name and location of the cemetery, and the date of application. After receiving a completed application, the quartermaster clerks would verify the information on the applications. Pencil marks are often found where clerks made clarifications regarding details of service. Staffers also glued office memorandums to the applications as they were being processed, which remain adhered to the documents today. One type of memorandum clarifies name spelling. Because the carvings on a headstone were permanent, extra consideration was given to ensuring correct information. If clerks found a spelling discrepancy between the application and the records of the War Department, they attached instructions to provide correct information on the application and returned it to the applicant.

Sometimes clerks wrote or glued verifying or, on occasion, supplementary information about a veteran's service. On the application submitted by John Turner of the Wisconsin Veterans' Home in Waupaca, Wisconsin, for Peter A. Ladd and Andrew Britten, Ladd's service is summarized on a typewritten slip as "enlisted in the navy August 20, 1864, and was discharged June 14, 1865, as ordinary seaman. The termination of his service was of honorable nature." Britten's service was similarly summarized as "last enlisted in the navy September 27, 1864, and served as 1st class fireman to March 30, 1865, when he deserted." Such mentions of desertion were common but were often disproved and corrected in subsequent correspondence with the War Department. However, genealogists should beware that on occasion headstone applications were rejected due to proven dishonorable discharge.

The diligent researcher may also find other useful information. For example, the application for a headstone for John G. Wright, interred in the Pine Grove Cemetery in Lynn, Massachusetts, was submitted by James G. Brown, local post representative of the Grand Army of the Republic. In addition to the basic service information, the application includes the pension number of the Widow's Certificate No. 21322. For Ephriam Bailey from the Revolutionary War, one can trace the research of the quartermaster clerks through the compiled pieces of information from various sources in the War Department records that were attached to his headstone application.

Applications for private cemeteries are arranged by state and thereunder by county, regardless of the date of application. If the cemetery is unknown, an idea of the last county of residence may help in locating an application. Applications for Soldiers Homes are organized first by state, thereunder by the location of the home. Applications in this series include soldiers and veterans buried in federal and state soldiers homes. Both of these series may be perused at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. Researchers may also write to the reference staff of the Old Military and Civil Branch, Attn: Military Headstone Applications, 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20408-0001. Due to limited resources, however, only one headstone search per letter can be conducted.

Headstones for Veterans of Later Wars

Headstones for the graves of Indian war and Spanish-American War veterans remained the same as those for Civil War veterans. In 1903, however, the height of the stone for southern gravesites was increased to thirty-nine inches. Additionally, in this year, the use of the stone markers for unknown burials was discontinued, and those graves were also marked with headstones.

Following World War I, the top of the headstone was slightly rounded, and the height and width were increased to strengthen durability. For the sake of uniformity, veterans of previous conflicts continued to receive the same design as had been used for their comrades. In addition to name, rank, and state of veteran's regiment, headstones for World War I veterans included division and date of death. For the first time, a religious emblem was offered for those who desired it—the Latin Cross for those of Christian faith, the Star of David for followers of the Jewish faith. The Buddhist emblem, or Wheel of Righteousness, was added as a choice in 1951. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the secretary of war authorized use of flat markers of similar sizes to conform to the rules of some private cemeteries that did not allow upright headstones.

In 1925 the quartermaster revised the look of the headstone application as well, though the information requested did not substantially change. The full sheets of paper were exchanged for eight-by-five-inch cards (Applications for Headstones, 1925–1963 [RG 92, entry 2110 C]). The cards ask for name, rank, branch of service, company, regiment or ship, years of birth and death, date of application, name of honorably discharged veteran, if the veteran died while on active duty, dates of enlistment and discharge, address of cemetery, religious emblem (if designated), and the name and address of applicant and relationship to deceased. As on the older applications, some handwritten notations by the quartermaster clerks may be found, but the frequency and value of the markings diminish as the date of the applications grows more recent. Later applications also include the service number. These cards are organized roughly by year, thereunder alphabetically. The key to finding the desired application is knowing the date it was submitted. The first two sets within this entry encompass the years 1925–1941 and 1942–1948, thus a rough estimate of the year is all that is necessary to find an application. Segments thereafter are confined to two- or three-year spans. The applications for 1964–1970 found in RG 92, entry 1942A, are organized strictly by government fiscal year, and thereunder alphabetically. The information and organization reflect the earlier series. However, unlike the Headstone Applications for Private Cemeteries, the headstone applications for this series reflect burials in national cemeteries.

Reference staff can search a few ranges of dates for off-site researchers, but again, limited resources prohibit answering requests of more that one veteran per letter. For the headstone applications of 1925–1970, write to National Archives and Records Administration, Modern Military Records, Attn: Headstone Applications, 8601 Adelphi Road, Room 2400, College Park, MD 20740-6001.

Headstone applications after 1970 provide the same information and are similarly organized to the headstone applications described above. Although the series is dated 1965–1985, the bulk of the collection begins in 1970. In 1972 the national cemetery system, and the responsibility of providing headstones, was transferred to the U.S. Veterans Administration. Divided annually by fiscal year, and thereunder alphabetically, these records are found in the Records of the Veterans Administration (RG 15, entry 52), and include headstone applications for private cemeteries. Because the records are contemporaneous and provide information regarding the next of kin of the deceased, access to these records is limited to those who ordered the headstone. However, reference staff can make copies of such applications for researchers, redacting the sensitive information. Researchers should provide name of decedent and date of application to the reference staff of the Old Military and Civil Branch, Attn: Military Headstone Applications, at 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington DC 20408-0001. If the date of application is unknown, the staff will search the application based on date of death. Please keep in mind that due to limited resources, only one search per letter can be conducted.

Other records of interest in the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, include the Interment Control Forms, ca. 1928–1962 (RG 92, entry 2110B). Arranged alphabetically by the name of the decedent, these forms were used as records of control over burial lots in national cemeteries. The forms contain name of decedent; rank; units served; serial number; war of service; dates of birth, death, interment, service including enlistment, and discharge or retirement, if applicable; the place of burial and location of gravesite; next of kin; and sometimes burial location of spouse if in the same cemetery. Much of the information on these forms is similar to that found on headstone applications, but because these records are organized alphabetically, researchers unsure of a date of application should find these records easier to use.

Researchers looking for interment information for World War II veterans buried overseas should check a brief series of Headstone Inscriptions and Interment Records in the Records of the American Battle Monument Commission (RG 117, entry 43). Although the records cover only 1946 to 1949, they are also easier to use than the headstone applications because they are arranged alphabetically, regardless of year. Established in 1923, the American Battle Monument Commission was founded to honor the American armed forces where they served by monitoring and advising the construction of military monuments and markers on foreign soil by other nations. After World War II, American soldiers were exhumed from their temporary burial place and moved to one of fourteen sites selected by the secretary of the army and the ABMC, with the permission of the host country, to become eternal shrines to those who gave their lives in the course of the war.

Although not as extensive in information as the interment records and headstone applications, the ABMC headstone inscription and interment records offer name of decedent, rank, unit of service, state of residence, date of death, cemetery, and grave location. They also provide information about the next of kin and any awards earned by the deceased.

Many other series in the Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General located at both the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and the National Archives at College Park can be good sources of information regarding burial sites and other information. However, many of the series are incomplete and prove difficult to access. Researchers should be aware that navigating such series requires a great investment of time and diligence. Researchers interested in finding a burial location or other information relating to a veteran's burial should start with the appropriate series described above and may turn to other series if their searches prove unfruitful. Further research into the myriad other sources should be done on site at National Archives facilities with the benefit of reviewing the finding aids in our research room with the guidance of knowledgeable NARA staff.

See more in: Confederate Headstones

Mark C. Mollan is an archives technician in the Motion Picture, Sound, and Video Recordings unit, National Archives and Records Administration. He received his M.A. in history from Villanova University.