The International Civil Aeronautics Conference of 1928

Celebrating the Wright Brothers' First Flight

Winter 2003, Vol. 35, No. 4

By Charles F. Downs II

On December 8, 1927, President Calvin Coolidge wrote a short note to the Conference of the Aeronautical Industry meeting in Washington, D.C., expressing his interest in having an international conference in Washington the next year. He wanted to honor the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Wright brothers' first powered flight and to further establish the United States among the world leaders in aviation.

Twelve months later, Coolidge was welcoming aviation leaders and representatives from thirty-four countries to the U.S. capital. Between December 12 and 14, 1928, some of the most important figures in the new field of aviation gathered to exchange information and honor aeronautical achievements, especially those of the guest of honor, Orville Wright (Wilbur had died in 1912). Following the conference, the delegates even traveled to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to attend ceremonies on the site exactly twenty-five years after the Wrights' historic flight.

The International Civil Aeronautics Conference of 1928 was the first significant national recognition of the Wright brothers' achievement of powered manned flight. This year, as we celebrate the centennial of flight, it is appropriate to take another look at it.

The conference has long faded from historical memory. Even at the time, a State Department official dismissed it as "not anything of importance. . . . nothing but a celebration." No international agreements or regulations came out of the conference, yet the President of the United States and others felt the significance of the anniversary merited a high-level, international observance.

Since Orville and Wilbur Wright's historic flight a quarter century earlier, powered flight had come a long way. Airplanes were now accepted as part of the fabric of modern life. They had proved their military value in the recent world war and were increasingly finding roles in the civilian world, such as air mail service.

In many ways, the conference reflected the post-Lindbergh flight, pre-Depression euphoria of American aviation, when even the sky no longer the seemed to be a limit.

Once President Coolidge had expressed his interest in holding an international aeronautical conference in Washington, D.C., it fell to staff at the Commerce and State Departments to make the idea a reality. Little was done to implement the President's suggestion until late March 1928, when the assistant secretary of commerce for aeronautics, William P. MacCracken, wrote to the Department of State about planning the event. State Department officials resisted moving forward until an annoyed secretary of commerce, Herbert Hoover, sent a letter to the White House on May 4.

Hoover noted that though there had been much interest among the public, industry, and foreign governments in the proposed conference, the State Department requested "an official communication from you before sending in estimates for the budget." Hoover included an estimated budget of $24,700. In closing, he added, "It will be appreciated if you can express your approval for this project to the State Department."

Coolidge responded by scrawling on Hoover's letter "Ask State to send this up." A cover letter from Everett Sanders, secretary to the President, dated May 5, 1928, transmitted Hoover's letter to Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg, inviting his "attention to the personal notation of the President thereon."

Some in the State Department questioned the timing of such an aeronautical conference, since it was proposed for the same time as another major conference, the Pan-American Arbitration Conference. Assistant Secretary of State William R. Castle reassured a colleague on May 3, 1928:

This aviation conference is not anything of importance in that, as I understand it, there will be no attempt to draw up any kind of an agreement. It, after all, is nothing but a celebration of the anniversary of the first Wright flight. That is apparently why they want it on that particular date. MacCracken is utterly vague on the subject and I don't know whether he will get his appropriation or not. All they apparently intend to do is to have a three or four days session, read some papers and entertain the delegates and get them to go out to Chicago to see the aviation show which is held there.

State Department concerns quickly eliminated one justification originally given for holding the conference—to serve as a forum for the discussion for future international regulation of air travel. They noted that three days was far too short to accomplish anything of substance. In any event, State Department officials believed that they, not Commerce, should take the lead in conferences likely to produce international agreements.

After receiving Coolidge's note, Kellogg wasted little time in sending the request to fund the conference off for approval. On May 29, Congress authorized the President to invite foreign representatives to a conference on civil aeronautics and appropriated the necessary funds. Interestingly, the primary justification given in the congressional resolution was to promote contact by American manufacturers with foreign markets, while commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Wrights' first flight was secondary.

The State Department sent invitations to those countries with which the United States had diplomatic relations and called for papers on aeronautical development in these countries. The invitations also publicized the aeronautical exhibition scheduled for Chicago the week before the conference. Leighton W. Rogers, chief of the aeronautics and communications section in the Department of Commerce, was appointed executive director of the conference to oversee its organization and keep things running smoothly.

By August 3, invitations to those chosen to be on the conference's advisory committee had been sent out, with the first meeting planned for later in the month. Committee members included representatives from the Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce, National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the United States Chamber of Commerce, the Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aviation, the National Aeronautic Association, the Departments of State and Commerce, and the Army and Navy.

This group quickly made a number of decisions that would shape the character of the conference. Its purpose was "to provide an opportunity for a interchange of views upon problems pertaining to aircraft in international commerce and trade." No votes were to be taken on any question under consideration. A representative of the U.S. delegation would chair each session. He would not participate in the discussion but introduce the presenter of the paper, recognize those who wished to speak, and enforce time constraints on remarks.

Representatives of the aeronautical industries of foreign countries were to be considered distinguished guests, and the American delegation would decide who from American industry would be designated as distinguished guests. The general public was to be admitted to all sessions, but space would be reserved for delegates and distinguished guests.

One problem that the conference faced was Soviet involvement. Because the United States did not have diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, no invitation was sent to them. A representative of the Amtorg Trading Company wrote the conference asking if aeronautical organizations in the Soviet Union could send representatives. Amtorg was a company established in the United States by the Soviets that had placed orders for aircraft and equipment with American companies. On State Department advice, conference officials replied that, although the conference was not in a position extend a formal invitation to the Soviet government or any private Soviet aeronautical enterprises, Russian experts might be allowed to attend if they were affiliated with private American enterprises doing business with the Soviets.

On October 24, 1928, however, the Amtorg representative responded that the organizations in the Soviet Union appreciated the offer but could "not see their way clear to accept it . . . in the absence of an official invitation to the U.S.S.R. as was extended to other governments."

No sooner was the Soviet question settled than another arose. The League of Nations expressed its interest in securing an invitation to the conference. As noted in a memorandum of November 13, 1928, the State Department recommended a negative response. According to the memorandum, the League previously had "tried to secure representation at conferences in which this Government was directly concerned. . . . In each case, the United States courteously and effectively discouraged this intrusive tendency." The United States was not even a member of the League, the memorandum continued, and besides, all the member countries of the League had already been invited to send delegates.

A total of 77 official and 39 unofficial delegates from foreign countries attended, in addition to the 12 official American delegates, 43 technical representatives, 238 representatives, and 32 committee members, for a total official attendance of 441.

Before the business of the conference began, delegates had the opportunity to attend the International Aeronautical Exhibition in Chicago. The show featured American aircraft and technology, including nearly every American airplane in production, motors and accessories, special exhibits, and displays of foreign aircraft as well.

Air transportation to Chicago was provided to the delegates, but only from Cleveland. Ironically, as the program noted, "The uncertain weather conditions at this time of the year over the mountains intervening between New York and Cleveland, make flying the entire distance to Chicago uncertain. The part of the journey from New York to Cleveland must, therefore, be made by rail." Had the weather been unfavorable in Cleveland, the journey to Chicago would have continued by rail, but in the event, "a fleet of multimotored airplanes" winged the delegates to Chicago.

The next day, the delegates stopped in Dayton, Ohio, where they took tours of the U.S. Army Air Corps Material Division laboratories and Wright Field and attended a dinner given by the City of Dayton honoring its favorite sons, the Wrights. They then traveled by train to Washington on December 11, in time to register. The conference was held at the Chamber of Commerce Building, across Lafayette Park from the White House.

On Wednesday, December 12, as the honorary chairman of the conference, President Coolidge greeted the members with the opening address.

Twenty-five years ago, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, occurred an event of tremendous significance. It was the first extended flight ever made by man in a power-driven heavier-than-air machine. How more appropriately could we celebrate this important anniversary than by gathering together to consider the strides made throughout the world in the science and practice of civil aeronautics since that day and to discuss ways and means of further developing it for the benefit of mankind?

The first part of Coolidge's address was a summary of the history of flight, saluting the great aviation pioneers and flyers. The President, who was justifiably proud of his administration's accomplishments in aviation, did not fail to note them at some length in his address, citing impressive statistics on the expansion of air travel and improvements in regulation. His summation clearly expressed his belief that international air travel and commerce would do much to ensure future world peace.

All nations are looking forward to the day of extensive, regular, and reasonably safe intercontinental and interoceanic transportation by airplane and airship. What the future holds out even the imagination may be inadequate to grasp. We may be sure, however, that the perfection and extension of air transport throughout the world will be of the utmost significance to civilization. While the primary aim of this industry is and will be commercial and economic . . . , but no less surely, will the nations be drawn more closely together in bonds of amity and understanding.

Each day was devoted to a different topic: December 12, international air transport; December 13, airway development, including meteorology and communications; December 14, foreign trade in aircraft and engines. Selected papers of special interest were read in the morning plenary sessions and, along with the other papers, formed the topics for discussion in the afternoon sub-sessions. General topics included air transportation, airway development, aeronautical research, aerial photography, aero propaganda (or, more correctly, public relations), trade in aircraft and engines, and private flying and competitions.

On Wednesday at 5 p.m., President Coolidge received the delegates at the White House. Afterward, Secretary of Commerce William F. Whiting (Hoover's successor) hosted a reception at the Chamber of Commerce Building. The next night, the delegates watched a specially produced film, Twenty Five Years of Flight. Afterward, a number of aviation pioneers were presented to the assembly, including Orville Wright, who was greeted with enthusiastic applause. On Friday, after the final formal session, the American delegation hosted a banquet for the foreign delegates.

On Saturday morning the delegates were treated to aerial displays at Bolling Field and Anacostia Naval Air Station by army air corps, navy, and Marine Corps fliers. In the afternoon, they toured the Bureau of Standards laboratories before boarding the steamship District of Columbia to sail to Norfolk, Virginia, where they arrived Sunday morning. The 220 delegates on board next toured NACA's nearby Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratories, where they witnessed demonstrations of Langley's unique wind tunnels. After group photographs, they returned to Norfolk, spending the evening on the steamer.

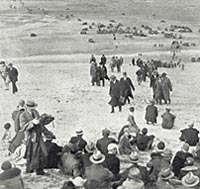

The delegates' next destination was Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, for ceremonies honoring the Wrights. Getting them there was a formidable logistical challenge. Paved roads ended seventy miles from Norfolk. For the rest of the trip they had to travel on sand and clay tracks, temporary "corduroy" roads, and finally the packed sand of the beaches. Motorcoach buses could take the delegates only as far as Currituck Courthouse, North Carolina. Seventy private cars then took the delegates to Point Harbor, where the Roanoke Ferry Company made a special trip directly to Kitty Hawk, which was still a mile and a half from the site of the planned activities.

Flying the delegates to Kitty Hawk was impossible. Langley's chief test pilot, Thomas Carroll, reported that although there were large expanses of level ground, "numerous and large 'sink holes' or soft spots" made it very dangerous to land an airplane. "Landings should only be made there in an emergency with little hope of taking off again."

During planning discussions, NACA had suggested the reenactment of the Wrights' first flight, using "an extremely early Wright aircraft now in the Possession of the Army" as well as demonstrations of modern army and navy airplanes. Nothing came of these proposals, not in the least because of the unavailability of any early Wright "aeros" in airworthy condition.

Once at Kitty Hawk, another assembly of private automobiles took the delegates to a North Carolina barbecue and turkey lunch as guests of the Kill Devil Hills Memorial Association. They arrived at the memorial site on the afternoon of December 17, twenty-five years to the day after the Wrights' historic flight. At two o'clock, Secretary of War Dwight F. Davis laid the cornerstone of the planned national monument at the top of the dune.

The gathering then proceeded downhill to a place that had been carefully identified by surviving eyewitnesses as the exact spot where the original Wright flight had started. Senator Hiram Bingham, president of the National Aeronautical Association, spoke and unveiled an inscribed ten-ton granite boulder to mark the site.

Amelia Earhart made the trip as an official guest rather than a delegate. In Amelia Earhart, A Biography (1989), Doris Rich writes that Earhart was delighted that she was considered an important enough personality to be a guest of the government. According to an account by local North Carolina photographer Dixon MacNeil, Earhart, accompanied by Reed Landis and the her trans-Atlantic pilot Wilmur Stulz, "commandeered" two horses and a wagon in order to make her way from the ferry to the monument site, collecting a number of other celebrities along the way, including the Russian-born aviation innovator Igor Sikorsky. Still, she managed to be standing beside Orville Wright and Senator Bingham for a widely distributed photo of the unveiling of the marker, no doubt to the approval of her publicity-conscious future husband, George Putnam.

Although he attended other conference activities, Charles Lindbergh was conspicuous by his absence from the ceremony at Kitty Hawk. He expressed his regret that he had a previous engagement in New York City. It was also said that Lindbergh believed that it was Orville Wright's day, and he did not want to take away from it by his presence.

The release of a flock of navy carrier pigeons to flutter their way home to Norfolk signaled the end of the ceremonies. The pigeons probably had a better return trip than the delegates and spectators, as their return home was compared unfavorably to Napoleon's retreat from Moscow by the New York Times reporter on the scene. If the trip to Kitty Hawk had been arduous, the return was an ordeal, when thousands of spectators tried to leave this isolated spit of sand at one time.

The delegates' final arrival in Washington, D.C., from Kitty Hawk marked the last official activity related to the conference. There is no shortage of praise for it in the files. A. B. Barber, of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, wrote MacCracken, "The Aeronautical Conference was, I feel, a great success—at least that was the unanimous reaction which I got from the delegates at the time and from others who have spoken of it."

Industry giant Chance Vought, a technical representative to the American delegation, wrote to MacCracken: "The conference was very much a success. The industry and the American public owe a great deal to you and your Department for putting it across, and I want to add my personal felicitations and congratulations for the job you did." A letter from an engineer with the General Electric Company noted that "It was a wonderful program and I know you will be pleased to have me say that it was a real inspiration to all of us."

Apparently the White House agreed. Presidential secretary F. Stuart Crawford wrote MacCracken on December 19: "I should judge the conference was a great success in every way, due, I am sure, in no small measure to your energy and ability."

As a sidelight to the official twenty-fifth anniversary observances of the Wrights' achievement, many international aeronautical organizations in the United States and worldwide held ceremonies and banquets. MacCracken had sent messages to a number of them and received letters of thanks and good wishes in return. One letter from the president of the Royal Aeronautical Society, contained a bit of irony:

The Royal Aeronautical Society held a Dinner last night in the Science Museum at South Kensington in the shadow of the wings of the original Wright Aeroplane on which twenty-five years ago the brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright made the first flights ever made by man in a power-driven aeroplane.

This sentence brought home the unwelcome truth that the actual Wright "Flyer" that had made the historic flight was in a British museum and unavailable for the observances in the United States. Orville Wright himself had loaned it to the British because of his unhappiness with what he believed was the Smithsonian Institution's failure to give him and his brother full credit for their achievement. This situation would not be resolved until after World War II, when officials of the Smithsonian placated Orville, and he allowed the Flyer to be returned to its place of honor in its homeland.

The long-term impact of the International Civil Aviation Conference in establishing the United States as the world leader in civil aviation was muted by the effects of the Depression. While the period of the 1920s and 1930s are characterized as "Aviation's Golden Age," the aviation industry faced daunting challenges over these two decades.

The Air Commerce Act of 1926 and the enthusiasm generated by Lindbergh's trans-Atlantic flight had sparked a speculative "aviation boom" in the last quarter of the 1920s, a "bubble" that was popped by the Great Depression. Much of the value of aviation stock evaporated. A weakening economy, punctuated by the stock market crash in 1929, dried up both markets and access to investment capital. Into the 1930s, the industry struggled to survive by various means, but many companies disappeared, went bankrupt, became inactive, or just scraped by on meager military contracts.

Along with much of the rest of the economy, the American aviation industry was crippled and left heavily dependent on air mail operations and export orders for survival. As even Henry Ford discovered, aviation was a notoriously difficult industry in which to make money.

Despite the problems faced by aviation as an industry, technological advances during this period were breathtaking. Designs went from wood and fabric biplanes to sleek metal monoplanes, with amazing increases in speed, range payload, and reliability. Aviation events made news, and record-breaking flights still captured the public imagination. But it was not until 1938, with defense production gearing back up, that the number of aircraft produced in the United States again approached 1928 levels.

No international agreements or conventions were produced by the conference, as none were intended. Its most lasting legacies may well be the two U.S. postage stamps issued to commemorate it. In the end, State Department officials may have correctly categorized it as "nothing but a celebration." Perhaps so, but it was still a fitting way to recognize the twenty-fifth anniversary of the day "America gave wings to the world!"*

* This phrase was used by Secretary of War Davis in his speech at Kitty Hawk, December 17, 1928, and appears on the postal cover commemorating the occasion.

Related stories:

- A Prince and a "Lady" of Uncertain Status

- More Than They Bargained For: Transcripts & Lawsuits

- Freedom of the Press Prevails

Charles F. Downs II was a senior appraiser with the Life Cycle Management Division at the National Archives and Records Administration until his retirement in December 2003. He has an M.A. in history from the University of Maryland and has been an archivist at NARA since 1978. He has worked with a wide range of civil and military records, including such specialized areas as diplomatic records, still pictures, and printed archives, and has a life-long fascination with aviation.

Note on Sources

The International Civil Aeronautics Conference seems to have made little or no impression on the popular historical consciousness. More surprising, it is rarely mentioned by those specializing in the 1920s, aviation history, or even by the biographers or in the papers of the participants. While the conference merited a few references in contemporary newspapers and periodicals, its story is most completely told in the records of the federal government in the holdings of the National Archives.

The first and most obvious place to look is in the records of the Federal Aviation Administration. Although the FAA did not exist in 1928, records of its predecessor agencies are located in RG 237. The Civil Aeronautics Administration's general correspondence file, 1926–1934, contains several folders related to the conference.

References in those folders to the State Department led to that agency's records. While there is some duplication of the CAA files, these two sources together provide a wonderful, if somewhat fragmentary, insider's view of preparations for the conference.

Primary Sources

National Archives at College Park, Maryland

Record Group 59, General Records of the Department of State, Decimal Files, Decimal 576.R1.

Record Group 237, Records of the Federal Aviation Administration, Records of the Civil Aeronautics Administration, General Correspondence, 1926–1934, File 606, International Civil Aviation Conference; File 805.30, Wright Memorial, Kitty Hawk, 1927–32.

Record Group 255, Records of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NACA "Biography" File (Correspondence, Reports and Other Records Relating to the Careers of Committee Members, 1915–58), Victory, James F., Folder "NACA Pilgrimage to Kitty Hawk, 1928." Still photographs 255-GF, folder 520, the ICAC delegates visiting the NACA Langley laboratories (three group photographs).

Record Group 342, Records of the United States Air Force, motion picture films 342-USAF-16170, "Commemorating the 40th Anniversary of the Wright Brothers First Flight," and -18082, "Wright Brothers News Clippings." These silent black-and-white films include contemporary newsreel footage of the conference, the delegates, and their excursions to Dayton and Kitty Hawk.

Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa

William P. MacCracken Papers, box 16, folder "The International Civil Aeronautics Conference, Washington, 1928," contains correspondence and publications related to the conference.

Official Publications

The Commerce Department's Aeronautics Branch endeavored to publicize the conference in its own bimonthly publication, Domestic Air News. Between July 31 and December 15, 1928, issues 33, 37, 38, 41, and 42 contained information concerning the conference. Issue 44, January 15, 1929, had a two-page "review" of the conference. The next issue, January 31, 1929, noted that the proceedings had been printed and were available from the Government Printing Office (GPO).

The official publications of the conference are classified under as S 5.28 in the Superintendent of Documents (SuDocs) classification system. Because the conference's official languages were English and French, all documents appear in both languages. Publications of the "The International Civil Aviation Conference, Washington, D.C., December 12, 13, and 14, 1928," consist of: Lists and Addresses of Foreign Official and Unofficial Delegates and American Representatives (25 pp.), Proceedings of the Conference (286 pp.), Papers Submitted by the Delegates to Consideration by the Conference (669 pp.), Rules of the Conference (3 pp.), and programs for the various events. President Coolidge's address was included in the Proceedings and was published separately as Address of President Coolidge to the International Civil Aviation Conference (SuDocs Pr 30.2 In8/2).

The official description of the proceedings at Kitty Hawk appeared as House Document No. 520 (70th Congress, 2nd sess.), "Twenty-fifth Anniversary of the First Airplane Flight, Proceedings at the Exercises Held at Kitty Hawk, N.C., on December 17, 1928, In Commemoration of the Twenty-fifth Anniversary of the First Flight of an Airplane Made by Wilbur and Orville Wright," U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1929.

See also William R. Chapman, and Jill K. Hanson, Wright Brothers National Memorial Historic Resources Study (National Park Service, January 1997).

The controversy between Orville Wright and the Smithsonian is well documented in aviation literature. Wright's own explanation, "On Why the 1903 Wright Aeroplane is Sent to a British Museum," was published in the magazine U.S. Air Services 13 (March 1928): 30–31, and appears in The Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, ed. Marvin W. MacFarland (1953), vol. 2, 1906–1948, pp. 1145–1148.

Newspapers

The New York Times, October, November, December 1928, and January 1929. The Times ran a number of articles on the conference and related topics.

The News and Observer (Raleigh, N.C.). Leon Rooke, "The N.C. Role in Aviation: It Did Not End With the Wright Brothers," September 30, 1962, outlines the career of photographer Dixon MacNeil and his association with aviation personalities, including those at the dedication of the Wright Brothers Memorial at Kitty Hawk.

Books and Periodicals

While there is an occasional passing reference to the conference, no substantive treatment of it appears in books or periodicals.