Bridging the Mississippi

The Railroads and Steamboats Clash at the Rock Island Bridge

Summer 2004, Vol. 36, No. 2

By David A. Pfeiffer

On April 22, 1856, the citizens of Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa, cheered as they watched three steam locomotives pull eight passenger cars safely across the newly completed Chicago and Rock Island railroad bridge over the Mississippi River. The first railroad bridge across the Mississippi was open for business. Now the people of eastern Iowa could reach New York City by rail in no more than forty-two hours.

The construction and completion of this bridge came to symbolize the larger issues affecting transcontinental commerce and sectional interests. Backers of a railroad across the country were divided between those who favored a northern route and those who advocated a southern one. The bridge also pitted steamboats against the railroads, and these disagreements were decided in the federal courts.

Two notable players in the controversy surrounding the bridge were men who would later face each other on a grander stage: Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. Lincoln was the attorney for the bridge company in litigation brought by the steamship interests. Davis, as secretary of war, took an active role in the contest between northern and southern routes for a transcontinental railroad.

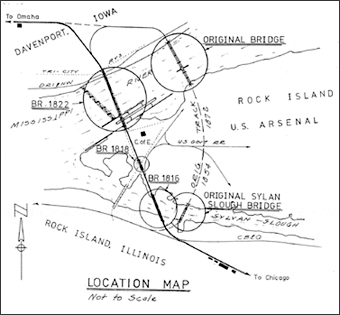

The Rock Island Bridge was built for the purpose of uniting the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad, which had just reached Rock Island from Chicago in 1854, and the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad in Iowa, which was building from Davenport toward Council Bluffs on the western end of the state during 1853. Proponents of the project touted Rock Island as an ideal location for the bridge as it provided a direct rail link between the city and state of New York, the Mississippi Valley, and the Far West. Project engineers, drawing on an 1837 topographical survey by Lt. Robert E. Lee and other surveys, deemed the site ideal.

Because the boundary between Illinois and Iowa was in the center of the main channel of the Mississippi River and both railroad's charters differed on their legal origin and terminal points, special legislation and a new charter was necessary to unite the two railroads. The problem was solved by an act of the Illinois legislature in 1853 incorporating the Railroad Bridge Company with the power to "build, maintain, and use a railroad bridge over the Mississippi River . . . in such a manner as shall not materially obstruct or interfere with the free navigation of said river." This condition would become a crucial point in future litigation.

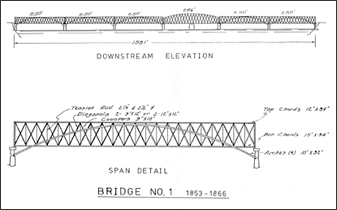

The construction of the bridge started on July 16, 1853, and lasted for three years. The construction involved three sections—a bridge across a narrow portion of the river between the Illinois shore and the island, a line of tracks across Rock Island, and the long bridge between the island and the Iowa shore.

The design of the long bridge was intended to present a minimum hazard to navigation. The total structure of the bridge was 1,581 feet long and was composed of six spans. The single-track bridge included a swing draw span placed directly over the customary steamboat channel with two fixed spans on the Illinois side and three on the Iowa side. The draw span rotated on a massive center pier with a top width of 32 feet and was supported by a turntable bearing arrangement with twenty wheels on a twenty-eight-foot diameter track. There was some thought to putting a roof on the bridge, but the idea was rejected because of the fear that sparks from locomotives might set fire to it.

Not everyone was happy about the construction of the bridge. The riverboat owners were against any bridge that they saw as an impediment to navigation. This opposition became the center of a successful test case that settled for all time the rights of the railroads and others to bridge navigable streams.

Initial Opposition to the Bridge

During the 1850s, a struggle was going on in the Mississippi Valley between those who favored north-south traffic and those who advocated east-west travel across the continent. It was a contest between the old lines of migration and the new; between the South and the East; between the slow and cheap transportation by water and the rapid, but more expensive, transportation by rail. It arrayed St. Louis and Chicago against each other in an intense rivalry. The people of the city of St. Louis and other river interests supported the principle of free navigation for boats, whereas the citizens of Chicago and the railroad interests stood by the right of railroad companies to build a bridge.

It was a struggle in which the river interests played a losing game. The steamboat could only follow the water systems, while the railroad companies could lay their rails almost anywhere. The construction of the Rock Island railroad bridge, built across the path of the Mississippi steamboats, brought the crisis to a head. Other railroads waited for the outcome of the dispute before going ahead with their plans to build bridges across the Mississippi.

Even the government opposed the building of the bridge. In 1853, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, then President Franklin Pierce's secretary of war, declared his interest in a transcontinental railroad by the southern route as a means of linking the Far West to the South. That same year, the Rock Island extended its line from Chicago to Rock Island and the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad broke ground at Davenport, Iowa. The Rock Island Bridge Company was formed and work on the bridge commenced in the fall of 1853. Southerners were opposed to any northern bridge because it would allow the north to settle the west in greater numbers. Davis made no objection at this time because he felt that the progress of the southern route seemed assured. In the spring of 1854, however, as the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act heated up sectional rivalries, Davis realized that his southern transcontinental railroad might be delayed. His interest in the Rock Island site grew.

As secretary of war, Davis had a direct interest in Rock Island. Until 1845, the army had maintained Fort Armstrong there. Even after the fort was closed, succeeding secretaries of war claimed jurisdiction over the island. The Rock Island Bridge Company therefore applied to Davis for a grant of land for a railway across the Mississippi River. Davis pondered his reply for several months while construction began on the bridge. Finally, on April 19, 1854, Davis reasserted the War Department's jurisdiction and declared that he opposed the company's use of the island. According to contemporary newspaper accounts, Davis did not want to permit a northern railroad route to get a head start over a southern railroad route, thereby allowing the north to take the lead in settling Nebraska and Kansas. In a letter to the contractors, John Warner and Company, he ordered construction on the bridge halted. The order was ignored.

On July 17 the U.S. marshal for the District of Illinois arrived at Rock Island to enforce Davis's order. By then the land had already been graded, and for some unknown reason, the marshal did not evict the bridge construction workers. Opponents of the bridge were forced to seek other means of halting construction.

Davis's next move was to apply for an injunction in federal court to restrain the Bridge Company from further construction. Judge John MacLean heard the case, the United States v. The Railroad Bridge Company, during the July 1855 term of the U.S. Circuit Court for Northern Illinois. Judge MacLean ruled that because Rock Island had been abandoned by the War Department, it could not be considered a military preserve. Therefore, Rock Island became public land and could be used for other purposes. The judge added that the bridge would be an improvement in the interest of the general public. Such use of public lands promoted population growth and increased land values. He maintained that "a State has the power to construct a public road through public lands." Finally, the judge concluded that "the State of Illinois has an undoubted right to authorize the construction of a bridge, provided that the same does not materially obstruct the free navigation of the river." He further stated that there would be little or no delay or hazard to steamboats resulting from passing the drawbridge. Jefferson Davis's efforts to halt construction of the bridge were effectively stopped.

The fight, however, was not over. On the morning of April 21, 1856, the bridge was completed, and the first trains rolled across it. Again, speeches were made and bands played. The Father of Waters had been crossed. Then disaster struck.

A Collision Brings the Bridge to Court

Just fifteen days after the celebration of the completion of the bridge, part of the bridge was wrecked and burned as a result of a steamboat collision. This incident set the stage for act two of the court battle that helped to settle the issue of whether railroads could cross navigable streams. This incident also brought into the public eye an Illinois attorney by the name of Abraham Lincoln.

The story goes like this. As darkness fell on the evening of May 6, the steamer Effie Afton moved slowly upriver toward the newly completed bridge. The vessel blew her whistle signaling that she was moving through the draw. The draw slowly opened and the steamboat moved through. Some two hundred feet after the Effie Afton cleared the draw, she heeled hard to the right. Her starboard engine stopped, the port power seemingly increased. She struck the span next to the opened draw. The impact caused a great deal of damage to both the bridge and the boat. Then a stove in one of the cabins was knocked over and its fire spread rapidly to the deck and then to the bridge timbers. The vessel burned to cinders within five minutes. One span was completely destroyed, and there was some pier damage as well as minor damage to the rest of the bridge. By the following day, the rest of the bridge caught fire and was completely destroyed. Steamboats up and down the river celebrated, blowing whistles and ringing bells.

The Effie Acton was new, well equipped, and worth about fifty thousand dollars. The accident occurred on her first trip above St. Louis. Her usual run was on the Ohio River and on the Mississippi between Louisville and New Orleans. According to the local newspapers, there was no evident reason for her appearance this far north on the river at night. In addition, there was at the time, apparently, no public record of who or what the boat carried or her destination. People in the Davenport-Rock Island area who favored the railroad were sure that the Effie Afton was loaded with something flammable and deliberately run into the bridge. They believed that if the boat had been drifting out of control, it would have drifted with the current in the channel and not touched the bridge pier.

On the other hand, the steamboat interests were loud in their condemnation of the bridge. They maintained that the bridge was an impediment to navigation and had caused the destruction of a fine vessel. Meanwhile, the bridge was repaired, and traffic was again crossing the bridge by September 8. It had been out of commission for only four months.

Shortly thereafter, Capt. John Hurd, owner of the Effie Afton, filed suit in the U.S. District Court at Chicago, demanding damages from the Railroad Bridge Company for the loss of his ship and cargo. The complaint alleged that the Effie Acton was carefully and skillfully navigated at the time and that the boat "was forcibly driven by the currents and eddies" caused by the bridge piers, resulting in the destruction of the boat by fire.

The Rock Island Bridge Company maintained that the accident, so-called, was in fact an intentional and premeditated act, a charge angrily denied by the shipowners. The impending litigation, officially docketed as Hurd v. Rock Island Railroad Company, promised to be the "battle of the century" for the competing transportation rivals. The case attracted national attention and proved to be the most notable of all of Abraham Lincoln's court cases.

Lincoln was hired as lead defense counsel as a result of a conversation between Henry Farnum, president of the Rock Island Railroad, and Norman B. Judd, the general counsel and a friend of Lincoln's. The two men, in conjunction with other officials of the Rock Island, realized that they needed a strong and popular man to handle the case. Judd remarked that "Lincoln was one of the best men to state a case forcibly and convincingly that I have ever heard . . . and his personality will appeal to any judge or jury."

Lincoln was already an experienced railroad lawyer when he accepted the case. From 1852 to 1860, he handled cases for the Illinois Central. Three times as an attorney for the Alton & Sangamon Railroad, he won cases that eventually came before the U.S. Supreme Court. He also had previously argued two cases in the U.S. District Court involving the question of the obstruction of navigable rivers by the construction of bridges. In one of these cases, he was legal counsel on the side of the river interests.

Lincoln almost always sought out the fundamental facts on which to base his case. He had a reputation of being very well prepared. He apparently was not satisfied with the explanations of the accident given by the bridge master, bridge engineer, and others. A few days after he took the case, he traveled to Rock Island to see the bridge firsthand. He walked out onto the bridge and, as the story goes, met a boy sitting out on one of the spans. He asked the boy if he lived around here and the boy replied, "Yes, sir. I live in Davenport. My dad helped build this railroad." Lincoln then asked the boy if he knew much about the river. When the boy answered in the affirmative, Lincoln laughed and said, "I'm mighty glad I came out here where I can get a little less opinion and more fact. Tell me now, how fast does this water run under here?

Lincoln and the boy figured out the speed of the river current under the bridge by timing how fast a log traveled from the island to the bridge. The boy who told this story was Benjamin R. Brayton, son of B. B. Brayton, resident engineer on the project, and who later was also a Rock Island engineer. Lincoln, with his customary thoroughness, studied other information concerning the current, speeds, eddies, and the traffic of the river, including the survey of the river done by Robert E. Lee. During the trial, Lincoln scored points with the jury with his intimate knowledge of the measurements of the bridge and the river.

Thus Lincoln was fully prepared as the case came to trial in the U.S. Circuit Court in Chicago, again before Judge John MacLean, on September 8, 1857. The roster of counsel appearing for Captain Hurd was impressive. The team was headed by Judge H. M. Wead of Peoria, the best "river lawyer" in the state. Judge MacLean, during his charge to the jury, said the whole case boiled down to one point: Was the bridge a material obstruction to navigation? The trial lasted fourteen days. Engineers, pilots, boat owners, rivermen, and bridge builders were subjected to examination and cross-examination by the opposing lawyers. Models of the steamboat and the bridge, along with many maps were exhibited. The conflict in testimony was direct and extensive.

Finally, after both sides had rested, Lincoln rose to make an eloquent, if lengthy closing argument in favor of the bridge. In his argument, Lincoln, as a former riverman, showed that he understood the romance of the Mississippi River and its boat life. St. Louis and the steamboat interests did what they had to do under the circumstances, and he did not blame them. Yet there was a growing travel from east to west that had to be considered that was as important as the Mississippi traffic. Lincoln declared that "It is growing larger and larger, building up new countries with a rapidity never before seen in the history of the world." In the year following the accident, the railroad had hauled 12,586 freight cars and 74,179 passengers across the bridge.

During four months of the year, winter weather made the river unnavigable, but the bridge and the railroad could be used. Lincoln analyzed the angles of the piers, the curve of the river, the depth of the channel, and the velocity of the current. He discounted the notions of a tunnel or a suspension bridge, saying that they were too expensive and that somebody would always build a steamship higher than the bridge. Lincoln maintained that the pilot drove his boat as though the river had no bridge with piers in it, and the starboard paddle wheel was not working. He declared that by no stretch of the imagination could a steamboat, out of control, get so far out of the current as to be able to hit the pier. However, the main focus of his argument was that one man had as good a right to cross a river as another had to sail up or down it. He perhaps melodramatically concluded that the fate of the civilization of the west was at stake.

Two days after beginning his summation, Lincoln finally came to a halt. He said that he had more to say, but that he had used up his time. The jury deliberated for a few hours and ended up as a hung jury. Therefore, the judge dismissed the case. The court's action was seen as a victory for railroads, bridges, and Chicago over steamboats, rivers, and St. Louis.

Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company was a crucial case in Lincoln's career and solidified his reputation as a great trial lawyer, which served him well when he ran for President three years later.

Bridge Opponents Continue the Fight

The fight, however, was still not over. During 1858, the Committee on Commerce of the U.S. House of Representatives conducted an investigation to determine if the Rock Island Bridge was a serious obstruction to the navigation of the river. The committee concluded that the bridge did constitute a hazard because of the length of the pier, the angle of the bridge, and the swift current under the bridge. The committee believed, however, that the courts should settle the matter and therefore did not recommend any action by Congress.

Predictably, in May 1858, James Ward, a St. Louis steamboat owner, filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Southern Division of Iowa asking the court to declare the bridge a nuisance and order its removal and restore the river to its original capacity for all purposes of navigation. After voluminous testimony, Judge John Love gave his decision on April 3, 1860, for the plaintiff. He declared the bridge a nuisance and ordered the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad to remove the three piers and their superstructure that lay on the Iowa side. The judge reasoned that if this bridge was not stopped, many other bridges would follow.

The piers were not torn out, for the railroad appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Mississippi and Missouri Railroad Company v. Ward came before the Court during its December 1862 term and was decided on January 30, 1863. That Court, although not by unanimous decision, reversed the decision of the district court and allowed the bridge to remain. Justice John Catron, writing for the Court, stated that because the jurisdiction of the Iowa court extended only to the middle of the river, removing the bridge on the Iowa side would solve nothing in the matter of obstruction. Furthermore, Catron reasoned that if Judge Love's decision was accepted, then "no lawful bridge could be built across the Mississippi anywhere; nor could the great facilities to commerce, accomplished by the invention of railroads, be made available where great rivers had to be crossed." One could not stop the inevitability of progress: that railroads needed to cross rivers.

This view was reaffirmed in another U.S. Supreme Court case, The Galena, Dubuque, Dunleith, and Minnesota Packet Co. v. The Rock Island Bridge. This case resulted from the appeal of a libel filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois for alleged damages done by the bridge to two steamboats. The plaintiff claimed that the bridge obstructed the free navigation of the river and that the bridge had done seventy thousand dollars' worth of damage to his steamboats. The court found for the plaintiff, and the property was attached.

The Mississippi and Missouri Railroad and others then filed an exception to the jurisdiction of the court to take a proceeding against the property. The district and circuit courts sustained the objection, and the case was dismissed. The railroad then requested the Supreme Court to confirm the correctness of this ruling. On December 30, 1867, the Court upheld the decision, and the bridge was allowed to remain. Speaking for the Court, Justice Stephen Johnson Field argued that "though bridges and wharves may aid commerce by facilitating intercourse on land, or the discharge of cargoes, they are not in any sense the subjects of maritime lien." A maritime lien could exist only upon movable things engaged in navigation (such as vessels, steamers, and rafts), not things that are fixed and immovable (such as a wharf, bridge, or real estate of any kind). The result of the decision was to establish for all time the right to bridge navigable streams. The way was legally clear to build more bridges over the Mississippi. Of course, by this time there were already several bridges across the river. This decision marked the effective end of the Rock Island Bridge litigation.

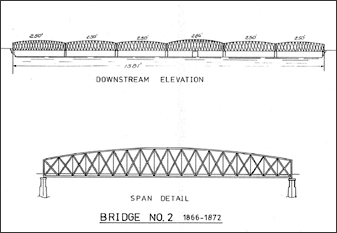

Two more bridges were built at the Rock Island site. The original Rock Island Bridge (rebuilt after the 1856 collision) did not have a long lifespan. During the Civil War, Rock Island was used as a Union prison camp for Confederate soldiers. After the war, the value of the island having been established, the government proposed that an arsenal be built on the island. In 1867 government officials and the Rock Island Railroad drew up an agreement granting the company a new right-of-way across the western (or lower) end of the island. The new bridge, opened in November 1872, was a double-decked structure owned and used jointly by the railroad and the government, giving rise to its nickname, the "Government Bridge."

As the years passed, the need for a double-track bridge grew. Most of the Rock Island mainline had been double-tracked, creating a bottleneck at the single-track bridge. Congress authorized work on a new double-track bridge, built on the piers of the existing bridge, in 1895. The new 1,850-foot-long bridge, which is the present bridge, was completed by November 1896 at a cost to the railroad of $305,732. The bridge was constructed of steel except for the iron track and the roadway systems.

With the increase in river traffic, the bridge has been the victim of many barge accidents over the years but has seldom been out of commission for more than a few hours.

The story of the building of the Rock Island bridge involved not only the physical construction of the bridge but also the larger issues of the rivalry of the north-south riverboat trade versus the east-west axis of railroads and westward migration. It pitted St. Louis and the river interests against Chicago and the railroads to determine which eventually would become the hub of Midwest commerce. The issue of the right to cross navigable streams was decided for all time. It also found Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln on opposite sides of a case with wider ramifications, involving issues that would soon bring the country to civil war.

Besides the Rock Island Bridge, other notable engineering monuments now dot the length of the Mississippi: the Huey P. Long Bridge in New Orleans, the Eads and Merchants Bridges in St. Louis, and the James J. Hill Stone Arch Bridge in Minneapolis. These bridges, along with the signing of the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railroad Act by President Lincoln in 1862 and the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, spurred westward settlement. However, history will remember that the Rock Island bridge was the first to cross the Father of Waters, thus removing the Mississippi River as a barrier to American railroads.

David A. Pfeiffer is an archivist with the Civilian Records Staff, Textual Archives Services Division, of the National Archives at College Park. He specializes in transportation records and has published articles and given numerous presentations concerning railroad records in the National Archives. He is the author of Records Relating to North American Railroads, Reference Information Paper #91 (National Archives and Records Administration).

Note on Sources

The case files for the two Rock Island Bridge U.S. Supreme Court Cases are located in the Records of the United States Supreme Court, Record Group 267, National Archives at College Park, MD: Entry 21, Appellate Case Files, 1792–2000, Case File #4092, Mississippi and Missouri Railroad Company v. Ward, and Case File #4685, The Galena, Dubuque, and Minnesota Packet Co. v. The Rock Island Bridge. Summaries of both of these cases (67 U.S. 485 and 73 U.S. 213) are located online at LexisNexis Scholastic Edition at www.lexisnexis.com.

Unfortunately, the court records for the U.S. District Court for Northern Illinois, and particularly the Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company case, were destroyed in the Chicago fire of 1871. The House of Representatives Report #250, 35th Congress, 1st session, entitled "Railroad Bridge Across the Mississippi River at Rock Island," April 15, 1858, is available in Record Group 233, Records of the House of Representatives, Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives, Washington, DC.

Secondary sources used and recommended concerning the construction and history of the Rock Island Bridge include Frank F. Fowle, The Original Rock Island Bridge Across the Mississippi River, Railway & Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin #56, 1941; John F. Stover, Iron Road to the West, American Railroads in the 1850's (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978); William Riebe, "The Government Bridge," The Rock Island Digest 2 (1982); John C. Parish, "The First Mississippi Bridge," The Palimpsest 3 (1922); William Edward Hayes, Iron Road to Empire: The History of 100 Years of the Progress and Achievements of the Rock Island Lines (New York: Simmons-Boardman, 1953); and the "First Bridge Across the Mississippi River Rivals Fiction for Drama and High Adventure," Rock Island News-Digest, October 1952.

Sources concerning Abraham Lincoln and his involvement with the Rock Island Bridge Company case are Albert A. Woldman, Lawyer Lincoln (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1936); John M. Starr, Jr., Lincoln and the Railroads (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1927); Bernie Babcock, "Lincoln and the First Mississippi Bridge," Railroad Man's Magazine (1931); Albert J. Beveridge, Abraham Lincoln, 1809–1858, vol. 1 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1928); Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln, The Prairie Years, vol. 2 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1926); and Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 2 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953).

For information concerning Jefferson Davis and the bridge, see Dwight L. Agnew, "Jefferson Davis and the Rock Island Bridge," Iowa Journal of History 47 (1949).