Sealing the Sacred Bonds of Holy Matrimony

Freedmen's Bureau Marriage Records

Spring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By Reginald Washington

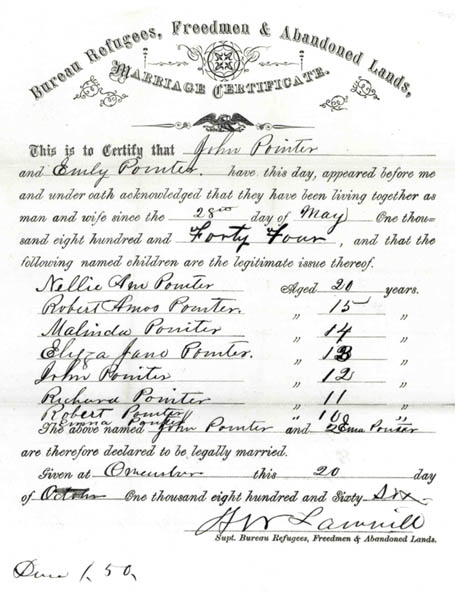

On April 19, 1866, former slaves Benjamin Berry Manson and Sarah Ann Benton White received an official marriage certificate from the Freedmen's Bureau, officially known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands.

The Wilson County, Tennessee, couple had lived as slave man and wife since October 28, 1843, and for the first time in more than two decades their marriage had finally received legal recognition. The Freedmen's Bureau—established in the War Department by an act of Congress on March 3, 1865—was responsible for "the supervision and management of all matters relating to the refugees and freedmen and lands abandoned or seized during the Civil War." With duties resembling those of a modern-day social services agency, the bureau provided freedpeople with food and clothing, medical attention, employment, support for education, help with military claims, and a host of other socially related services—including assisting ex-slave couples in formalizing marriages they had entered into during slavery.

For the Mansons—who had lived intermittently on separate farms—the marriage certificate issued by the Freedmen's Bureau was more than a document "legally" sealing the sacred bonds of holy matrimony. Listing the names and ages of 9 of their 16 children, it was for them a symbol of freedom and the long-held hope that they and their children would one day live free as a family in the same household. Two Manson sons, John and Martin, had fought for freedom during the Civil War with the 14th Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. A third son, William, would later serve several tours in the Regular Army defending the American West with the famed all-black regiments of the 24th and 25th Infantry.

Benjamin and Sarah Manson were not alone in their quest to put their slave marriage on a legal footing. When freedom came, tens of thousands of former slave men and women—some seeking to marry for the first time and others attempting to solemnize long-standing relationships—sought help from Union Army clergy, provost marshals, northern missionaries, and the Freedmen's Bureau.

Scattered among the aging volumes and paper files of the Freedmen's Bureau at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., are an impressive number of marriage licenses, certificates, registers, and reports documenting the federal government's efforts to aid in the legalization of marriages of former slave couples.

While there are other valued federal, state, private, and published sources that help document ex-slave marriages, the Freedmen's Bureau's marriage records are arguably some of the most important records available for the study of black family marital relations before and after the Civil War. For the increasing number of African American genealogists and family historians, this unique body of marriage records may hold the only formal proof of a slave ancestor's marriage.

Slave Marriages

Slave marriages had neither legal standing nor protection from the abuses and restrictions imposed on them by slaveowners. Slave husbands and wives, without legal recourse, could be separated or sold at their master's will. Couples who resided on different plantations were allowed to visit only with the consent of their owners. Slaves often married without the benefit of clergy, and as historian John Blassingame states, "the marriage ceremony in most cases consisted of the slaves simply getting the master's permission and moving into a cabin together."

Benjamin and Sarah Manson's marriage, however, had been graced with a formal ceremony. Benjamin, who was brought to Tennessee from Virginia as a young boy by his then-owner, Nancy Manson, later described the event in a pension application he filed as the dependent of his deceased son John: "We were married on Dr. L. W. White's farm 5 miles from Lebanon [Tennessee]. . . . Rev Ben White [a black preacher] said the marriage ceremony." The "wedding ceremony," he continued, "took place on the porch of the owner of Sarah [Dr. White]. . . . It was with the knowledge and consent of my master [Mr. Joseph L. Manson, son of Nancy Manson] and Sarah's master that we were married." Shortly after their marriage, Sarah's owner purchased Benjamin. "He [Dr. White] had me for a number of years," Benjamin explained, "then Mr. Manson bought me back and owned me till I was emancipated."

Formal marriage ceremonies for slave couples like Benjamin and Sarah were generally reserved for house servants. In such cases, slaveowners would have a white minister or a black plantation preacher perform the ceremony, and a large feast and dance in the "quarters" would follow honoring the slave couple. The ceremony could include the slave marriage ritual of "jumping the broom," which required slave couples to jump over a broomstick. The custom of jumping the broom could vary from plantation to plantation. On some farms, the slave bride and groom would place separate brooms on the floor in front of each other. The couple would then step across the brooms at the same time joining hands to signal that they were truly married. On other farms, each slave partner was required to jump backward over a broom held a foot from the ground. If either partner failed to clear the broom successfully, the other partner would be declared the one who would rule or boss the household. If both partners cleared the broom without touching it, then there would be no "bossin."

While historians and scholars differ on the origin, exact meaning, and the frequency of the "irregular" marriage ritual, most agree that the act of "jumping the broom" was a "binding force" in the slave couple's relationship and made them feel "more married."

The marriage arrangement of couples who resided on different plantations ("broad" marriages) was often the cause of great concern for most slaveowners. Fearing that slave marriages between plantations could potentially contribute to lost time from work and increase the risk of slaves developing attitudes of independence, owners encouraged their slaves to marry on the plantation where they lived. When this was not possible, wealthy owners would in some cases buy the spouse of his slave. Generally, slave men would receive passes to visit their wives on weekends, and those slave husbands, like Benjamin, who lived on a farm that neighbored their wife could visit nightly. Children of "broad" marriages were the property of the slave woman's owner, and the owner of a slave man had no legal right to their services. Between 1865 and 1867, most southern states in some form or another legalized former slave marriages and recognized the children of such marriages as legitimate.

Military Officials Take Action

Early efforts by the federal government to regularize freedmen marriages began with military officers and civilians who supervised "contraband" camps where freedmen sought refuge during the Civil War. For example, the Department of Tennessee and Arkansas in March 1864 issued orders directing Union army clergy to "solemnize the rite of marriage among Freedmen." The department produced marriage licenses and certificates, and chaplains and missionaries were given detailed instructions on when and how they should be used. The department maintained registers of freedmen marriages in part as a means to assist in identifying couples, resolve future questions involving inheritance, and to settle claims against the federal government, especially those concerning deceased black soldiers. Many of the "pre-Bureau" marriage registers, along with other marriage records created by wartime superintendents, were later turned over to the Freedmen's Bureau when it was formed.

The Freedmen's Bureau Issues Marriage Orders

On May 30, 1865, Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, who was appointed by President Andrew Johnson as commissioner of newly formed Freedmen's Bureau, issued orders to his assistant commissioners—who were responsible for the daily operations of the bureau in the former Confederate states, Border States, and the District of Columbia—on the conditions for solemnizing former slave marriages. Continuing the practice started by military and civilian officials at government camps, Howard told his subordinates, "In places where the local statutes make no provisions for the marriage of persons of color, the assistant commissioners are authorized to designate officers who shall keep a record of marriages, which may be solemnized by any ordained minister of the gospel." Howard's orders also required ministers to report on marriages they performed, including "such items as may be required for registration at places designated by assistant commissioners." Marriages that had been already recorded by military officers were to be preserved.

Assistant Commissioners Respond to Howard's Orders

Although Commissioner Howard's marriage orders provided important guidance for solemnizing ex-slave marriages, his instructions and the several ways in which assistant commissioners responded to them led to variations in the kind of data collected about freedmen couples. Because of these variations, the quantity of bureau marriage records differs for each state, and for some states there are no marriage records. In such instances, researchers will need to search in state and county sources for information regarding ex-slave unions.

Alabama

In response to Howard's marriages orders, the Alabama assistant commissioner issued a circular on September 7, 1865, suggesting a general remarriage of "all persons [freedmen] married without licenses, or living together without marriage," and that it might be necessary to keep "separate book records" of such remarriages. Probate judges, who acted as bureau agents, were told to suspend the marriage bond requirements and in certain situations to reduce marriage fees. Couples who had not properly resolved previous relationships were ineligible to receive licenses. When the Alabama State Convention adopted a measure on September 29, 1865, legalizing former slave unions, the assistant commissioner's office simply informed freedpeople of the law but offered no additional guidance nor attempted to register or issue licenses and certificates in the state.

Arkansas and Missouri

On June 24, 1865, the Arkansas field office, which had jurisdiction over both Missouri and Arkansas, instructed its officers "to keep and preserve a record of marriages of freed people, and by whom the ceremony was performed." The Arkansas General Assembly later legalized ex-slave marriages and required that a record of such marriages be kept by county clerks. In Missouri, because Howard believed "good laws [had been] passed protecting the rights of freedmen," Freedmen's Bureau operations by mid-October 1865, with the exception of matters concerning freedmen education and the processing of military claims, were largely withdrawn.

However, less than a month after the Arkansas office issued its initial orders, officers there began forwarding monthly reports of marriages for parts of Missouri and various subdistricts in Arkansas to Howard's office. Missouri reports include lists of marriages performed at Cape Girardeau (July and August), Pilot-Knob, and one marriage at St. Louis (August 1865). The marriages performed at Cape Girardeau were compiled from a register maintained by the Freedmen's Bureau's disbursing officer stationed there. They contain such information as the names and ages of the couples, dates of marriage, where married and by whom, and the number of male and female children born to couples.

Reports for Arkansas sent to the commissioner's office document freedmen marriages performed during the period of July 1865–September 1866 in the subdistricts of Arkadelphia, DeVall's Bluff, Hamburg, and Helena. The reports contain more information about freedmen couples than those for Missouri. There is, for example, such additional information as the couple's color and place of residence, the color of the their parents, the number of years the couple lived with another person, how they were separated, the number of children by a previous relationship, and the names of witnesses and the minister or official who performed the marriage. The Arkansas subdistrict field offices also maintained registers and or issued marriage certificates in the subdistricts at Arkadelphia (1865–1867), Dardancelle (1866), Fort Smith (1865–1867), Hamburg (1866), Jacksonport (1865–1868), Lewisburg (1866), Little Rock )1864–1866), Madison (1867), Napoleon (1866–1867), Osceola (1866–1867), Paraclifta (1865), Pine Bluff (1864–1867), and Washington (1865–1867).

Maryland, Delaware, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia

The District of Columbia field office established an office of the superintendent of marriages. The superintendent's office advised freedmen of the act of Congress of July 25, 1866 (14 Stat. 236), which stipulated that "all color persons" in the District who recognized each other as man and wife prior to the law were now legally married and their children legitimate. At various times, Maryland, Delaware, and several counties in West Virginia and Virginia (transferred to the Virginia Bureau in September 1866) were under the jurisdiction of the bureau's field office in the District of Columbia. In early spring 1866, an office of the assistant commissioner for Maryland was established, and by 1867 Delaware and West Virginia were placed under its control. On March 22, 1867, the Maryland General Assembly legalized freedmen marriages and required couples to file their marriages with local court officials.

Most of the registrants recorded in a District of Columbia register (November 1866–July 1867) had moved there from neighboring Maryland and Virginia, and many had lived in long-standing relationships. Nearly half of the registrants had been married as slaves without the benefit of a formal marriage ceremony. Bureau officers recorded the name of the couple who were issued the marriage certificate, the date and name of the minister who issued the certificate, the former residence of the ex-slave couple, the year in which the slave marriage had taken place, the name of the minister who performed the marriage, the number of children born to the couple, and in some instances, comments from the minister about the couple he registered. The marriage superintendent also issued marriage licenses and certificates and forwarded copies of them along with marriage reports (1866–1868), including reports of couples who were living together but not yet married, to Howard's office.

Marriage records found in the files of the Office of the Commissioner relating to Delaware all appear to concern proof of marriage in military claims filed with the claims division of the Freedmen's Bureau. One affidavit among the Delaware files concerns a marriage that was performed in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. There is no evidence in Maryland bureau files that suggest that officials there registered or issued marriage licenses and certificates in Maryland, West Virginia, or Delaware.

Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina

From June to September 1865, both Florida and Georgia were under the jurisdiction of the Freedmen's Bureau in South Carolina. In late summer 1865, the assistant commissioner for South Carolina issued an elaborate set of "marriage rules" for all three states. The marriage rules outlined the duties of former slave couples and who was eligible to marry and remarry, who could grant permits and solemnize marriages, the responsibilities of husbands to former wives, and the rights of wives and children. Each state passed legislation legalizing freedmen marriages that contained basically the same provisions as the marriage rules issued by the assistant commissioner for South Carolina. There is a report of marriages and marriage licenses/certificates for Jacksonville, Florida, in the records of the Office of the Commissioner (1864–1865) that was issued by the provost marshal for the District of Florida when the state was under martial law. Also in those records is a single marriage certificate (probably submitted as proof for a military claim) for South Carolina, and in the files of the South Carolina office of the assistant commissioner is a set of the marriage rules. There is no evidence, however, that the bureau registered or issued marriage licenses and certificates in Florida, Georgia, or South Carolina.

Kentucky, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Mississippi

Bureau officials in Kentucky, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Mississippi provided guidance and issued marriage licenses and certificates and registered freedmen marriages. None of these states had laws pertaining to the unions of ex-slave couples as of May 1865, but Tennessee and Mississippi enacted laws by 1867 requiring former slave couples to register their marriages with local county officials. In Tennessee, if local officials refused to issue licenses, qualified Freedmen's Bureau officers were authorized to perform marriage ceremonies and issue licenses and certificates. Mississippi law prohibited marriages between blacks and whites, and any persons who intermarried were guilty of a felony and subject to fines and life in prison. In addition, under Mississippi law persons were deemed black who were of "pure negro blood, and those descended from a negro to the third generation inclusive, though one ancestor of each generation may have been a white person." Similar laws defining race and prohibiting interracial marriages existed for many of the southern states.

For Kentucky, there is a single marriage license and a certificate in the records of the Office of the Commissioner. However, in the records of the Kentucky subdistrict field offices there are marriage licenses and certificates and registers for the subdistricts of Augusta (1866 and 1867), Bowling Green (1865–1867), Columbus (1866–1867), Cynthiana (1866), Mount Sterling (1866), Owensboro (1866–1868), Paducah (1865–1866), and Winchester (1866).

The records of the Office of the Commissioner contain a relatively large quantity of marriage certificates for Louisiana (1864–1867), Tennessee (1863–1866), and Mississippi (1864–1866) that include similar data about freedmen marriages. The records provide the names and ages of couples, their color and the color of their parents, the number of years both the husband and wife lived with another person, the reason for separation, the number of children together and from previous marriage, and other marriage-related data. In the Louisiana subdistrict field office there are registers of marriages for the subdistricts at the Bragg Home Colony (1865), Donaldsonville (1866), Mansfield (1865), and Shreveport (1865–1866). In records of the Tennessee assistant commissioner is a single marriage license (1865), and for the Tennessee subdistrict field office there are marriage registers for the subdistricts at Lebanon (1865), Memphis (1863–1866), and Trenton (1865–1866).

Four marriage registers maintained by the Mississippi assistant commissioner (1864–1866) are basically registers that were started by the Mississippi Freedmen's Department, and many of the marriage certificates that were forwarded to the commissioner's office for Mississippi relate to the registrants. The registers for Davis Bend, Vicksburg, and Natchez, Mississippi, document the registration of more than 4,000 freedmen from Mississippi and northern Louisiana. More than half of the soldiers registering marriages for Natchez were members of the Sixth Mississippi Heavy Artillery of the U.S. Colored Troops. Nearly all of the soldiers registering marriages for Davis Bend served with the 64th Colored Infantry. The Mississippi subdistrict field offices also registered freedmen marriages and issued licenses and certificates in the subdistricts of Brookhaven (1865), Columbus (1865), Davis Bend (1865), Goodman (1865), Grenada (1865), Jackson (1865), and Pass Christian (1866).

North Carolina

In recognition of a March 10, 1866, measure enacted by the North Carolina legislature that legalized ex-slave marriages, the office of the bureau's assistant commissioner for North Carolina issued a circular outlining the provisions of the law and instructed subordinate officers to make all freedmen in their districts aware of the new rules and the urgency for complying with them. Once informed of the law, tens of thousands of North Carolina freedmen couples reported their marriages to county courts. It appears that even before the North Carolina statute was enacted, some freedpeople were already applying for marriage licenses in the state. In the records of the Freedmen's Bureau's North Carolina office of the assistant commissioner at Raleigh, there is an October 10, 1865, report of 20 couples who received marriage licenses from the county clerk's office at Charlotte (Mecklenburg County) during July–September 1865. There are, however, no other series of marriage records for North Carolina among bureau files.

Texas

There were no specific laws in Texas governing ex-slave marital relations when Commissioner Howard issued his orders on the subject. When Texas became a republic in 1836, slaves were prohibited from marrying even with the consent of their owners, and free blacks could not live in the state. The bureau's assistant commissioner for Texas issued a circular in March 1866 containing marriage rules and encouraged the Texas legislature to recognize the marriages of former slave couples who lived in accordance with the state's common law marriage practices. The question concerning marriages of "persons of color" was eventually addressed by the Texas constitution of 1869, and an act of the state legislature on August 15, 1870, legalized the marriages of persons "formerly held in bondage" and declared their children legitimate. By this time, however, Freedmen's Bureau activities in Texas, with the exception of matters relating to freedmen education, had been withdrawn from the state. There is no evidence in Texas bureau records that the field offices registered or issued marriage licenses and certificates.

Virginia

In a circular dated March 19, 1866, the assistant commissioner for Virginia, Col. Orlando Brown, ordered his subordinates to register the names of freedmen who were "cohabiting together as man and wife" and to "take pains to explain to colored persons . . . that they [were] firmly married by the operation of the law." As the basis for his order, Brown cited two February 27, 1866, acts of the Virginia General Assembly that made provisions for issuing marriage licenses and the registration and legalization of marriage relations entered into by former slaves. Brown forwarded to Howard's office reports of marriages that contained the names and ages of couples, their place of residence and birth, names of parents, and occupation. Most of the couples named in the reports were either born or resided in Gloucester County. In response to Brown's orders, officers in 1866 in the Virginia subdistrict field offices registered marriages for the subdistricts of Goochland, Lexington, Louisa Courthouse, and Lovington. The information found in the files for these subdistricts, for the most part, reveals that a significant number of the registrants were farm laborers and field hands and many had lived in long-standing marriages.

While solemnizing freedmen marriages represented a small fraction of the Freedmen's Bureau's efforts to assist freedpeople, the bureau's surviving marriage records are of incalculable value for black family research. Although incomplete, the records provide an important glimpse into the lives and marital relations of the tens of thousands of ex-slave couples like Benjamin and Sarah Manson who, in spite of their condition, managed to maintain a sense of family and sustain long-lasting relations.

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) has produced on microfilm Marriage Records of the Office of the Commissioner, Washington Headquarters of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1861–1869 (M1875). This microfilm publication is part of a multiyear project to preserve and increase the accessibility of Freedmen's Bureau field office records, where many of the extant bureau marriage records and the vast majority of genealogy-related records are found.

To date, NARA has microfilmed the field office records for Alabama, Arkansas, District of Columbia, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland/Delaware, Mississippi Freedmen's Department ("Pre-Bureau Records"), Mississippi, Missouri, and North Carolina. Through a cooperative arrangement with the University of Florida at Gainesville, NARA has microfilmed the Freedmen's Bureau field office records for Florida. When the Freedmen's Bureau Preservation Project is completed, all of the field office records for the remaining states of South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia will be available on microfilm at the National Archives Building, Washington, D.C., and at each of NARA's regional facilities.

For access and inquires about the use of the records, researchers should visit or write (e-mail) the Old Military and Civil Branch, 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20408. For the location of previously filmed and future Freedmen's Bureau microfilm publications, researchers should contact the nearest regional archives or visit the NARA online microfilm catalog.

Note on Sources

Benjamin and Sarah Manson's marriage certificate is found in the Tennessee marriage records, Records of the Office of the Commissioner, Washington Headquarters of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, Record Group 105, at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. The records have been reproduced on microfilm as Marriage Records of the Office of the Commissioner, Washington Headquarters of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1861–1869 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1875, roll 4). Although the type and quantity varies with each state, the marriage records sent to the Washington, D.C., headquarters that are reproduced on this microfilm publication are from Alabama (one document), Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, South Carolina, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. For other records relating to freedmen marriages reproduced for the Freedmen's Bureau field offices, see microfilm publications M1901 (Arkansas), M1902 (District of Columbia), M1904 (Kentucky), M1905 (Louisiana), M1826 and 1907 (Mississippi), M1908 (Missouri), M843 (North Carolina), and M869 (South Carolina).

Compiled military service records for John White (also known as John Manson [private/corporal, Company I, 14th USCT]) and Martin Clark (also known as Martin Clark Manson [corporal, Company G, 14th USCT]) are found in Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops, Infantry Organizations (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1822, roll 16), Records of the Adjutant General's Office, Record Group 94. The original enlistment papers for William D. Manson (private, January 3, 1872, and January 23, 1883, Company H, 24th Infantry Regiment; private, April 23, 1890, Company F, 25th Regiment) are also located in Record Group 94. Pension files for John (WC699089) and Martin (WC591325) can be found in Records of the Veterans Administration, Record Group 15.

Background information on slave marriages was obtained primarily from three secondary sources: John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (Oxford University Press, 1979); Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South (Oxford University Press, 1980); and Eugene D. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (Vintage Books, 1976).

Records relating to the U.S. military's involvement in formalizing freedmen marriages can be found in Records of the Adjutant General's Office (Record Group 94) and the Records of the U.S. Army Continental Commands (Record Group 393, Part I). The Report of the General Superintendent of Freedmen, Department of the Tennessee and State of Arkansas for 1864 (Memphis, Tennessee, 1865) is also extremely helpful in understanding the U.S. military's marriage efforts.

For information concerning laws enacted by southern states, see Laws of Southern States, In relation to freedmen, 1865–1866, Entry 49, Miscellaneous Records 1865–1871, Records of the Office of the Commissioner, Washington Headquarters of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, Record Group 105; see also United States Senate, Laws in Relation to Freedmen, Senate Ex. Doc. 6, 39th Cong., 2nd sess., serial vol. 1276; and Branetta McGhee White, Somebody Knows My Name: Marriages of Freed People in North Carolina County by County, 3 vols. (Iberian Publishing Company, 1995).

Other secondary sources used in writing the article include Black Family Research: Records of Post–Civil War Federal Agencies at the National Archives, Reference Information Paper 108 (National Archives and Records Administration, 2004); George Bentley, A History of the Freedmen's Bureau (Octagon Books, 1974); Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the Civil War (Da Capo Press, Inc., 1989); Christopher A. Nordmann, "Jumping Over the Broomstick: Resources for Documenting Slave Marriages," NGS Quarterly 91 (September 2003); Herbert G. Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750–1925 (Vintage Books, 1976); and Elaine C. Everly, "Marriage Registers of Freedmen," Prologue: Journal of the National Archives (Fall 1973).

Author

Reginald Washington is the African American genealogy specialist at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. He is the author of Black Family Research: Records of Post–Civil War Federal Agencies at the National Archives, Reference Information Paper 108 (National Archives and Records Administration, 2004).