Getting the Message Out

The Poster Boys of World War II

Summer 2005, Vol. 37, No. 2

By Robert Ellis

The images and the messages on these government-produced posters, by some of the nation' s most famous artists, are as powerful today as they were 60 years ago.

There is Norman Rockwell's unequaled Four Freedoms—a series of paintings depicting the four freedoms that Franklin D. Roosevelt outlined as our reasons for supporting the Allied cause in World War II: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

J. Howard Miller's famous We Can Do It poster, sometimes known as "Rosie the Riveter," provided the message that even with so many men in uniform, America's plants and factories would keep on producing war materials, with women filling many of those vital jobs.

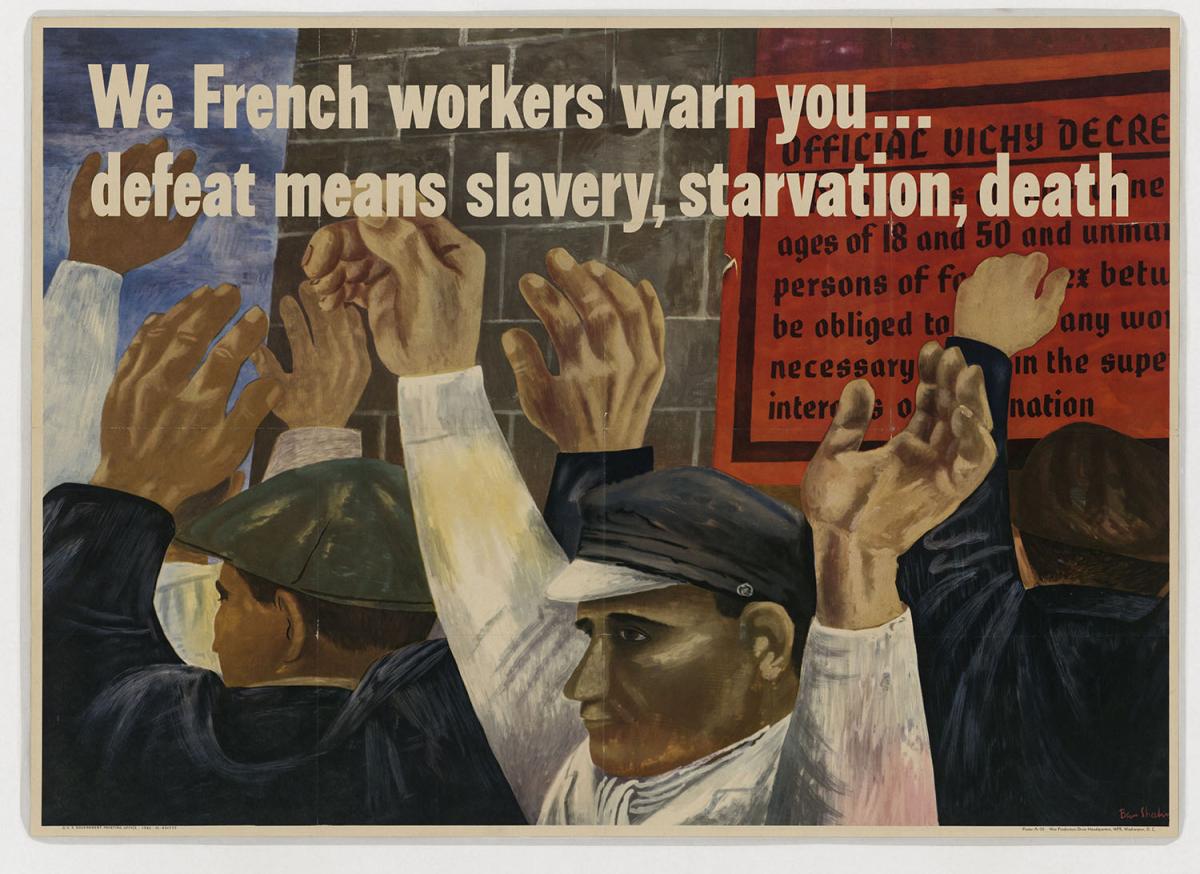

Thomas Hart Benton's The Sowers depicts grotesque images of German soldiers sowing skulls as seeds in a barren field, telling Americans that the German war machine was sowing death in every country they conquered. And Ben Shahn created a poster with the message: We French workers warn you . . . defeat means slavery, starvation, death.

These were just a few of the thousands of posters produced and distributed by the Office of War Information (OWI) during World War II to persuade the American people to support the war effort, to conserve the nation's vital resources, to buy saving bonds, and to not reveal possible national secrets.

To get these messages out, however, the federal government turned not to its own employees or to its military. The government mobilized the Boy Scouts of America.

The massive distribution of posters across the United States during World War II was a challenge. The OWI realized that posters had to be placed in street-level windows of every store, office, restaurant, and "service establishment of every kind" in the United States in order to reach the greatest number of people.

Before President Roosevelt established the Office of War Information by executive order on June 12, 1942, four different federal agencies disseminated government information to the public: the Foreign Information Service, the Office of Facts and Figures (OFF), the Office of Government Reports, and the Division of Information of the Office of Emergency Management. By combining so many different divisions, branches, and offices into one central organization, Roosevelt sought to avoid conflicting and confusing government statements.

The President had cause for concern. When conflicting reports about the loss of naval vessels and the number of lives lost at Pearl Harbor surfaced, the American public began to doubt the official reports from the U.S. Government. To reestablish the trust of the people, President Roosevelt created the OWI and directed it to develop information programs to foster an informed and intelligent understanding, at home and abroad, of the status and progress of the war effort and of the government's war policies, activities, and aims.

Because the OWI's mandate covered both foreign and domestic audiences, two branches were created: the Overseas Operations Branch and the Domestic Operations Branch. Within the Domestic Operations Branch, the Bureau of Publications and Graphics was established to coordinate the clearance, coordination, production, printing, and distribution of government posters and graphics.

OWI's goal was ambitious: to place posters in every city and town across the United States. The agency's plan called for an ongoing system of distribution; posters would be exchanged for new ones every two weeks. To accomplish its goal, the OWI formed a National Retail Committee, with local chapters in cities and towns across the United States. Each local committee would establish the necessary distribution outlets. For the plan to work, enthusiastic involvement of citizens was crucial. Each committee solicited the help of local store owners, executives of the Boy Scouts of America, and whenever possible a member of the local Victory Display Committee.

Collectively these local groups had some impact on the subject matter of the posters they would receive. The National Retail Committee sent local committees and the Boy Scouts sketches for their approval.

The OWI asked various other professional and volunteer organizations to help distribute its posters. The most important of these organizations were the Outdoor Advertising Association of America (OAAA), Western Union, the Association of American Railroads, the National Retail Association, and various women's organizations.

Women were essential to the war effort as workers and consumers. When the OWI decided to design a series of posters on how to save the fat in food, it targeted its poster campaign to women, especially female factory workers, nurses, and homemakers—all of whom were rationing food. OWI found a willing advocate for this poster's distribution at a national publication. Mrs. Louise Sloane, promotion director of Woman's Day magazine, coordinated the "Join Up" campaign by mailing posters to the YWCA, the New York Federation of Women's Clubs, the American Red Cross, and the American Legion Auxiliary. Owners of beauty parlors were also encouraged to display the posters, especially those relating to rumors, rationing, and the recruitment of nurses.

The OAAA organized an Outdoor Advertising Advising Committee, which encouraged members to be responsible for the distribution of 250,000 one-sheet posters a month. The committee gave outdoor advertising businesses exact directions on how to display the posters. Each outdoor billboard held 24 different sheets pasted together to form a single image. The OAAA decided to place the one-sheet OWI poster, which measured 1/24 of the total area of all the combined sheets, in the lower right-hand corner of each billboard. The larger picture was therefore unbroken save for where the OWI poster was prominently displayed.

Companies whose businesses spanned a large geographical area also helped distribute the OWI message. These included the outlets of Western Union and Postal Telegraph offices, the Association of American Railroads, the Pullman Company, and the Cab Research Bureau. Many small posters were placed in approximately 35,000 coaches by the Association of American Railroads. The Pullman Company also pledged to put national security and anti-rumor posters in every Pullman car. The American Taxicab Association, the National Association of Taxicab Owners, the United Association of Motor Bus Operators, the Cab Research Bureau, and the American Transit Association pledged to put posters in every cab.

The Boy Scouts of America was the main workforce for OWI's poster distribution system. Thousands of young men were responsible for the delivery of OWI's posters to shops all across the United States.

Founded in the United States in 1910, the Boy Scouts of America was a well-established organization when World War II began. In 1942, at the start of the OWI's ambitious poster distribution program, Edward Dodd, chief of the Division of Production and Distribution at OWI, asked the scouts to help: "Officials in Washington do not know of any other way by which they can meet this emergency except through the help of the Boy Scouts of America."

As soon as war was declared, the leaders of the Boy Scouts realized that they could be of service. Walter W. Head, president of the Boy Scouts of America, and James E. West, Chief Scout Executive, telegraphed President Roosevelt on December 8, 1941, the day Congress declared war, offering "the full and whole-hearted co-operation of our organization."

The scouts were a popular choice for jobs that needed to be done. In 1941 some scouts already operated a messenger service for the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD), collected aluminum and books, planted trees, and, possibly, did every job some local official could imagine. Boy Scouts were a natural choice for work at the grassroots level in the United States. In 1942, there were 1,600,000 members, and almost every village, town, and city had a scout troop. They also had complete knowledge of their neighborhoods. In addition, being clean-cut children and young adults, they could approach individual homes and businesses and be readily welcomed. The OWI's Dodd thought it would "be a great mistake not to take advantage of the eagerness of this organization to serve in this capacity."

The scouts received their first assignment in October 1942, when they distributed a poster that was based on the theme of Columbus Day. The poster, which was produced by the Office of Inter-American Affairs, commemorated the 450th anniversary of Columbus's first voyage. The artist was Howard Chandler Christy, who had painted many of the posters produced during World War I. Even on their first assignment, the Boy Scouts proved that they could distribute the posters with great speed. With only 24 hours' notice, the Boy Scouts of America was able to enlist the help of 544 of its local council offices. Thus the scouts proved they could deliver posters efficiently within a short amount of time.

In every community of more than 2,500 people, the scouts would distribute posters to stores located on the street level every two weeks. Approximately 2,300 communities participated in the program. The OWI shipped posters to a central distributing outlet in a community, such as a large department store. The Boy Scouts then would pick up their posters and distribute them to the smaller stores. Each adult scout leader in his community was responsible for making sure the scouts distributed the posters correctly.

At first, African American scout troops distributed only posters with African American themes. The poster featuring Dorie Miller, an African American who received the Navy Cross for heroism under fire at Pearl Harbor, was at first distributed only through channels in the African American community, such as Boy Scout troops, churches, restaurant, and benevolent organizations. On June 25, 1941, President Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 8802, which banned discrimination against government and defense workers because of race or color. In May 1943, Jacques DunLany, the chief of OWI's Production and Distribution Division, suggested that the agency might be criticized if it continued to single out the African American scouts as distributors of posters with African American themes, adding that the boys might feel "they were being 'segregated' or even 'discriminated' against." While African American scouts continued to distribute posters to mainly African American establishments, the OWI made sure they also received the same posters as any scout troop.

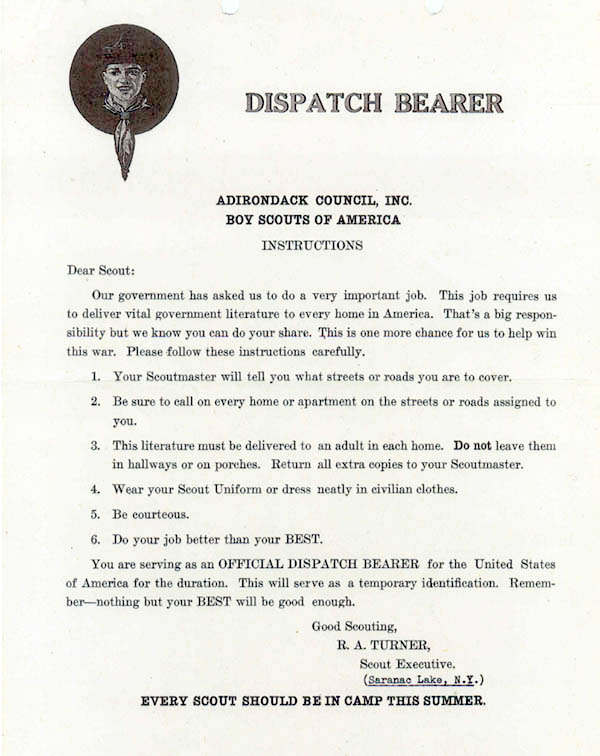

The Boy Scouts of America wanted to be officially and formally recognized by President Roosevelt as America's main distributor of government information. On February 16, 1943, President Roosevelt signed a letter asking the scouts "to take an important commission as Government Dispatch Bearers for the Office of War Information." The Boy Scouts of America would become the "Official Dispatch Bearers" for the OWI; each scout would receive "a certificate commission for him to carry to the people of the community vital information prepared by the Government." Through this program, the federal government kept 1,600,000 young people working to spread its messages to civilians all across the country.

Because Boy Scouts could not deliver posters to bars and taverns, the OWI turned to other groups to distribute "Don't Spread Rumors" posters in places where liquor might encourage loose talk. The National Conference of State Liquor Administrators reached out to bars and taverns. Baltimore's liquor licensing commissioner, Mr. C. Delano Ames, persuaded more than 2,800 liquor licensees to put the Don't Talk. The Enemy Is Listening poster in their establishments. In Baltimore and Providence, Rhode Island, the police departments delivered the posters. Later, brewers and distilleries distributed the posters through their salesmen and delivery trucks. Seagrams was one of the first distillers to distribute posters warning against loose talk. In addition, they also distributed table tents and menus with warnings against loose talk and other security themes. DunLany was so impressed that he wrote, "we would like to say to all distillers using similar point-of-sale material . . . Go thou and do likewise."

The OWI also ran into difficulty over gas rationing. The Boy Scouts of America wanted adults working with the scouts to distribute posters to be eligible for supplemental rations. On August 25, Richard C. Harrison, chief of the Gasoline Branch of the Office of Price Administration (OPA), denied the Boy Scouts' request. Harrison acknowledged that "distribution of Government posters is undoubtedly highly useful to the OWI but that this work is not so important as to justify a grant of preferred mileage." On September 20, 1943, Elkert K. Fretwell, chief Boy Scout executive, again asked OWI for extra gasoline for his leaders. Fretwell remarked, "Right or wrong, they have come to expect OWI to help them in this particular direction."

The Boy Scouts were not to be put off so easily and claimed that the OWI had offered them gasoline on five occasions in the past and then had not followed through on its promises. In a letter to Harrison, the Boy Scouts stated that their "only hope is to go to the highest possible authority and try to influence an authoritative voice to direct the rationing officials."

On December 6, 1943, the leaders of the Boy Scouts warned that if "professional scouters did not receive additional gasoline rations . . . our OWI Dispatch Bearer program . . . would be endangered." DunLany concluded the matter by declaring: "In order to make the policy of this office clear . . . this office [OWI] is not going to make further overtures to the OPA for additional gasoline rations."

Tension between leaders of the OWI and the Boy Scouts increased for other reasons. When DunLany traveled Fifth Avenue in New York from 34th to 57th Street on January 19, 1944, he wrote that he had found "NOT ONE SINGLE POSTER. . . . [A]ny distribution system that fails completely to achieve even a token showing on the nation's number one thoroughfare must have something very wrong with it." But perhaps there was more to this story. William H. Howard, executive vice president of R.H. Macy and Company, Inc., replied to DunLany's criticism:

You should spend a little more time acquainting yourself with the procedures set up for the distribution of OWI posters before . . . implicat[ing] their distribution system has something very wrong. . . . In your files you will discover that the Boy Scouts undertook to break a very embarrassing log jam for OWI who was finding it impossible to get its posters distributed to retail stores at all.

In fact, if OWI had shown even a fraction of the organizational ability, efficiency, and eagerness to do the job that the Boy Scouts of America had shown from the day they undertook their assignment, the problem would have been satisfactorily handled much earlier.

By 1944, however, perhaps DunLany's criticism of the BSA was justified. In fact, the secretary of the treasury, traveling on the Fourth War Loan Bond tour, reported that he and his entourage did not see one of the war loan posters the scouts were responsible for in the cities of Cleveland, Indianapolis, and Bridgeport. OWI media analyst David Martin felt that the Treasury Department would not use the Boy Scouts of America for further bond drives.

There may in fact be a reason why some posters might not have been hung. At one time, for example, members of the Business Men's War Committee of Peckville, Pennsylvania, complained that the larger chains received posters before they did. Some posters were reportedly too large for some of the windows in retail stores. For example, Norman's Rockwell's Four Freedoms posters measured 30" x 56". In addition the OWI was so efficient at churning out new posters every two weeks and grocers were receiving so many posters, that they had no room for their own advertising.

The Office of War Information was no longer necessary when World War II came to a close. The agency was officially disbanded by President Truman in 1945. With its closing, the distribution of posters across the United States also came to an end. In all, thousands of posters had been distributed. While it might be impossible to measure the impact that the OWI's message had on the millions of people who saw the posters, one could argue that the process of their distribution had mobilized an army of citizens at home. The individual scouts of the Boy Scouts America must be given much of the credit of distributing posters.

Robert Ellis is a reference archivist in the Old Military and Civil Branch at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Mr. Ellis is responsible for the records of the United States Supreme Court, the United States Court of Claims, and the District Court for the District of Columbia.

Note on Sources

The information for this article was taken primarily from the following materials at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland: Record Group 208, Records of the Office of War Information, Records of the Bureau of Graphics, Entry 236, General Records of the Chief, 1942–45, Folder Boy Scouts; and Entry 238, Letters Sent, 1943–44. Reference has also been made to Allen M. Winkler, The Politics of Propaganda: the Office of War Information, 1942–1945 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978), and to John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980.)