The Story of the Female Yeomen during the First World War

Fall 2006, Vol. 38, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

By Nathaniel Patch

I've been in frigid Greenland and in sunny Tennessee,

I've been in noisy London and in wicked, gay Paree,

I've seen the Latin Quarter, with its models, wines, and tights,

I've hobnobbed oft with Broadway stars who outshone Broadway lights;

But North or South or East or West, the girls that I have met

Could never hold a candle to a Newport yeomanette.

—Newport Recruit, 1918

Women in today's military answer their country's call in all services and ranks. Until World War I, however, the military establishment did not officially accommodate women who wished to serve. Some women had to dress like men to fight in the field, and others risked their lives as frontline nurses, but these brave women were not recognized by the military.

At the turn of the 20th century, the progressive social movements advocated women's rights, but it took the first global war to give women the opportunity to prove themselves.

World War I was the first industrial war. It introduced new weapons like the machine gun, airplanes, tanks, battleships, and submarines. Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare propelled the United States from neutrality to war. The submarine, introduced to world navies around 1900, evolved from a coastal-bound vessel to a terror on the open seas. When unrestricted submarine war began in January 1917, the German navy sank 540,000 tons of shipping in the first month. In April 1917, the month's total had risen to 900,000 tons, several thousand of them American. Because Germany refused to stop sinking American shipping and Great Britain increased pressure for American intervention, the United States entered the war.

The Naval Act of 1916 Opens the Door

The call to arms went out, and hundreds of thousands of men volunteered for or were drafted into military service. Even with increase of manpower, the Navy remained shorthanded. The number of ships increased from three hundred to a thousand.

How were these new ships going to be manned? The answer lay in the unassuming language of the Naval Act of 1916, which unintentionally opened the door to women volunteering in the U.S. Navy. As in previous wars, women were prohibited from joining the Navy and other Regular armed services.

But the act's vague language relating to the reserve forces did not prohibit women. The act declared that the reserve force within the U.S. Navy would consist of those who had prior naval service, prior service in merchant marines, were part of a crew of a civilian ship commissioned in naval service, or "all persons who may be capable of performing special useful service for coastal defense." This last element contained the loophole that allowed women to enlist.

After reviewing the act, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels and the Bureau of Navigation (the forerunner to the Bureau of Personnel) concluded that the language did not prohibit women from enlisting in the reserves. The act gave the Navy a previously untapped resource that allowed administrative operations to be carried out by naval personnel and freed able-bodied men to serve aboard ships.

On March 19, 1917, the Bureau of Navigation sent letters to the commanders of the naval districts informing them they could recruit women into the Naval Coast Defense Reserve to be "utilized as radio operators, stenographers, nurses, messengers, chauffeurs, etc. and in many other capacities in the industrial line." The new enlisted women were able to become yeomen, electricians (radio operators), or any other ratings necessary to the naval district operations. The majority became yeomen and were designated as yeomen (F) for female yeomen.

The Navy began recruiting women immediately, but it had no provisions for medical examinations or standards to which they were going to hold new recruits. Some recruiting offices were able to borrow female nurses from nearby naval hospitals to conduct the examinations.

At the beginning, it was assumed the yeomen would perform only administrative duties, so the majority of the tests focused on office skills. In spite of the confining categories the Navy placed upon the yeomen (F), the women also worked as mechanics, truck drivers, cryptographers, telephone operators, and munitions makers.

The Navy faced two problems specific to the new yeomen (F): living quarters and a dress code. A large number of these young women were assigned to posts away from home. Because the Navy had no protocol for women on naval bases, the female yeomen had to make their own arrangements for living quarters. Some were lucky and could find a place to stay with family or friends nearby. Many yeomen roomed at the YWCA or shared other apartments.

In some cases, the Navy helped. In Washington, D.C., the Navy leased some apartments for female yeomen who did not live locally. As the war progressed, housing became such a problem in Washington that the Navy proposed building dormitories for the beleaguered yeomen. The war ended before any of the construction projects began. In Newport, Rhode Island, the Navy housing conditions were so deplorable that the secretary of the Navy agreed to a subsidy to pay for room and board.

Standard Navy uniforms were tailored for men, but the Navy had no provision to supply women's clothing. At the time, it was still considered improper for women to wear anything but a dress or skirt. The solution was to lay down guidelines on what was to be considered regulation dress, and the yeomen (F) were given additional money to purchase what they needed. The uniforms of the yeomen (F) varied because they were either homemade or purchased outfits. Navy regulations later stated that uniforms had to be either white or blue. A single-breasted jacket topped a skirt whose hem had to be four inches above the ankle. Hats tended to be a brimmed hat made of a stiff felt. By the end of the war, the Navy had made changes to the regulations that governed gloves, hats, jackets, skirts, and handkerchiefs.

The yeomen (F) enlisted for the standard four years. Days before the signing of the Armistice in November 1918, the Navy stopped enrolling women but made no decision on what to do with women already in service. It was assumed they would finish their enlistments, and for some that period would end in 1922.

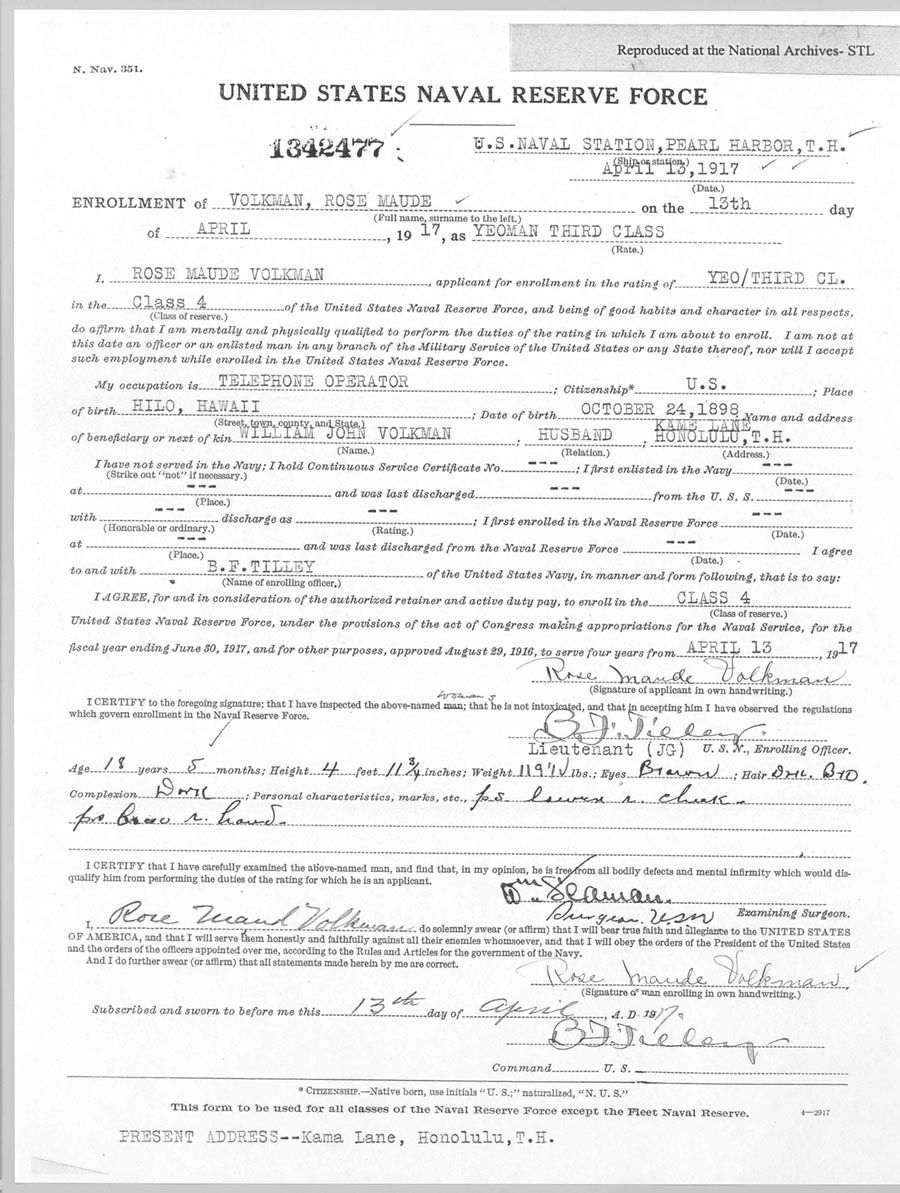

In 1919 the Navy made its first move to dismantle the women reserves. The Naval Appropriations Act of 1919 placed both Navy and Marine female reservists on inactive duty. Because they had not been discharged, they had to keep their uniforms and medical information. The Navy was also willing to pay for passage to return home or to the place of recruitment. In one special case, Yeomen Rose Volkman was recruited in her home in Hawaii and transferred to New York. The Bureau of Navigation investigated who had ordered this assignment because they were now responsible for paying $300 for her return passage.

The Navy was not so shortsighted as to willingly lose such a valuable resource as the services the yeomen (F) provided. Before the passage of the Naval Appropriations Act, Secretary Daniels advised the Navy and Marine commanders of civilian positions that would open within the Department of the Navy and at shore establishments. Appointments to these positions, such as clerks, messengers, or police, would be offered to reservists for a temporary period. Those who accepted the appointments kept their rate of pay and received bonuses to compensate for losing living expense allowances that they had got during their service. At the end of the appointment, usually six months, the former reservists had to take the civil service exam to become permanent federal employees. In most cases, the majority of the yeomen (F) within an office applied and accepted appointments.

The official end of the yeomen (F) classification came by a special act. Secretary Daniels cut their enlistments so that all yeomen (F) would be discharged by October 24, 1920. But because of negligence of naval district commandants, many yeomen (F) remained on the books well past the discharge date. Some stayed on because they were in charge of the final processing of the yeomen (F). It was reported that the last yeoman (F) was discharged in March 1921.

Resources in the National Archives

There are four main sources of records at the National Archives for conducting genealogical research on the yeomen (F):

- Military service records available at the National Military Personnel Records Archive in St. Louis, Missouri;

- Record Group 24, Records of Bureau of Naval Personnel;

- Record Group 38, Records of the Chief of Naval Operations; and

- Record Group 45, Records of the Office of Naval Library and Records.

Before beginning research, collect some basic information about the yeoman (F), such as her name, where she served, and when she served. Other kinds of information like her rank, date of enlistment, and place of enlistment are also useful, but the first three items are essential for using the records.

The grandest gem of genealogical resources is the service record. The female yeomen have service records just like their male counterparts because they were enlisted into the naval reserves. In 2004 the Department of the Defense signed over 1.5 million service records to the National Archives as permanent records. In July 2005, the National Archives opened the first research room for the purposes of researching service records from the early 20th century. The Navy personnel records begin in 1885 and end in 1939. Because the personnel records are no longer under the mandate of the Department of Defense and are considered public records, anyone can request a service record regardless of relationship to the veteran.

A service record includes the veteran's name, date of enlistment, place of enlistment, place and date of birth, address at the time of enlistment, and where the veteran trained and worked. The service record also provides information relating to discharge, quality of service, changes in rank, and other issues relating to discipline and merits.

To develop the stories of the yeomen (F), consult muster rolls in Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, located in the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. Muster rolls were taken every four months and they list all personnel currently serving or who have transferred, changed rank, or otherwise departed since the last muster roll. The majority of the yeomen (F) will be listed on either shore establishments or in naval district muster rolls. None of the yeomen (F) served aboard warships, and a very few were transported overseas.

Muster rolls are arranged by name of ship, shore establishment, or naval district. Within the muster roll, the names are in alphabetical order. The only drawback in using these records is that if the yeoman (F) is listed only in a naval district, it is difficult to reconstruct the department and learn who she worked with.

A muster roll lists the name and rank of a person. In most rolls, the female yeomen are listed as yeoman (F) rather than yeoman. Women also filled jobs other than yeomen, and their ranks would reflect that they were electricians or worked in a munitions factory. The rolls also indicate where and when a yeoman enlisted, when she was received at her duty station, and what department she worked for.

The muster rolls also list changes in a person's service, either in a separate section or in a column on the regular roll. Changes included promotions, demotions, arrivals, transfers, and even death. The muster rolls contain the most information about the yeomen (F) besides the service records.

During the First World War, as in any war, the government investigated people who were suspected of committing espionage, sabotage, or general troublemaking. The Espionage Act of 1917 made it illegal to interfere with an Allied victory and defined interference as spying, promoting the enemy, and speaking out against the war or recruitment. Within Record Group 38, Records of the Chief of Naval Operations, are the records of the Office of Naval Intelligence. One of the many tasks ONI performed was to investigate internal naval matters from troublesome personnel to counterespionage.

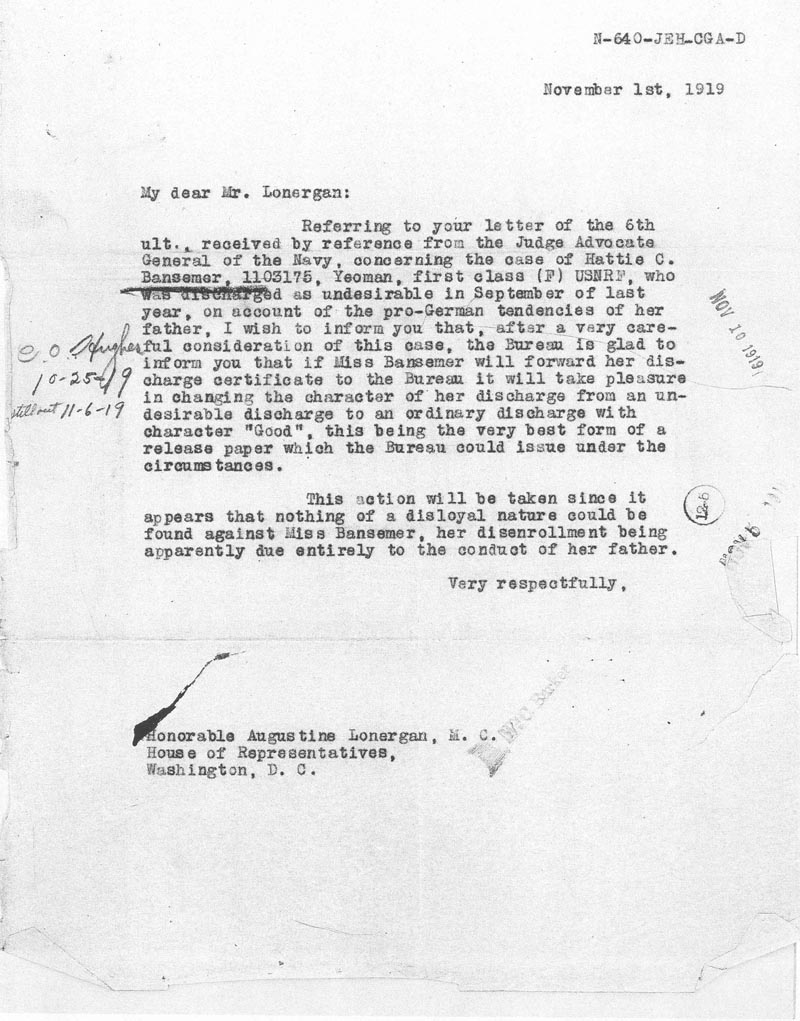

The yeomen (F) were not above suspicion. Yeoman 1st Class Hattie C. Bansemer served in the Second Naval District as a switchboard operator at the Communications Office at the Naval Base in New London, Connecticut. In early 1918, the authorities accused her father, Gottlieb Benjamin Bansemer, of having pro-German sympathies and arrested him for violating the Espionage Act.1 Bansemer, a German immigrant and prominent citizen in Hartford, Connecticut, owned a coal company. The Office of Naval Intelligence's (ONI) file on the Bansemers contains several affidavits from co-workers and peers testifying to Gottlieb's anti-American and pro-German sentiments.

Even though the ONI did not find any evidence of any disloyalty, the Navy dismissed Yeoman Hattie Bansemer on September 16, 1918, because of the sensitive nature of her job. In October 1918, Hattie filed a formal request to be reinstated.2 In 1919, through an advocate in the U.S. House of Representatives, Hattie appealed to the Navy Department to have the nature of her discharge changed from dishonorable to honorable.3 The appeal was successful, and her military service record indicates an honorable discharge.

Yeoman Bansemer's file was located in the confidential correspondence files from 1913 to 1924. The confidential correspondence files have both an alphabetical name index and a subject/country index. The files contain all the information filed by ONI that was relevant to their investigations. In the case of Yeoman Bansemer, her file contains a wealth of genealogical information because the Navy investigated her and her family's background. This includes places and dates of birth, their address at the time of the investigation, and affidavits that include names of co-workers and neighbors as well as names of employers.

The last major resource is Record Group 45, Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library. This record group comprises different types of naval records beginning with the Revolutionary War Navy and includes records relating to personnel, ship construction, naval operations, and shore establishments. The main finding aid is Inventory 18, Inventory of the Naval Records Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library. Because information about the yeomen (F) is contained within other documents, the researcher will need to know something about the subject, such as where she served or what duties she performed, to locate specific references.

This is a good record group to look at if you wish to flesh out stories of the yeomen (F). The yeomen (F) suffered casualties during the war, although all were noncombat. According to published sources, between 22 and 57 yeomen (F) died in service. The causes of death include accidents, suicide, and influenza. A search of the "List of Officers and Enlisted Men of the Regular Navy and the Naval Reserve Force Who Were Reported Dead or Missing During the Period, 1917–19"(Entry 266), turned up a card describing the death of Yeoman Mary Agnes Monahan. The 3-by-5-inch card listed her name, rank, and where she was serving. It also listed the date, place, and cause of death. She had enlisted in the naval reserve on March 12, 1918, in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Navy assigned her to the captain of Boston Navy Yard. Yeoman Monahan died in a car accident in Hampton Falls, New Hampshire, on September 10, 1918.4 The muster roll of the First Naval District ending September 30, 1918, also notes the date of her death.5

Photographs of the yeomen (F) are located at the National Archives in College Park in Records of the Bureau of Construction and Repair(19-G) and Records of the Department of the Navy (80-N). The Naval Historical Center located at the Washington Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., also has a collection of records and photographs related to the yeomen (F).

The social impact of the yeomen (F) reached beyond merely replacing men in shore establishments and naval shipyards. The five-year program opened the minds of their male peers to the women's abilities. The service of the yeomen (F) certainly assisted in the passing of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote. The yeomen (F) also created the precedence that gave rise to the WAVES in the Second World War. Their example also reached out beyond the Navy to all services. Since the First World War, women have taken on a greater role in the military achieving higher ranks and decorations for their achievements.

Nathaniel Patch is an archives specialist in the Modern Military Reference Branch at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. He is on the Navy Reference Team and is currently working on a master's degree in naval history.

Notes

Special thanks to the National Military Personnel Archives for their assistance in providing copies of the servce records of Yeoman (F) Hattie Bansemer and Yeoman (F) Rose Volkman, which provided needed information that aided in the writing and illustration of this article.

A good history of the yeomen (F) is Jean Ebbert and Marie-Beth Hall, The First, The Few, The Forgotten: Navy and Marine Corps Women in World War I (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2002).

1. Subject Hattie C. Bansemer, Section One New Haven, CT, July 15, 1918; Confidential Correspondence, 1913–24; Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI); Records of the Chief of Naval Operations, Record Group (RG) 38; National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, D.C.

2. Hattie C. Bansemer, Y1c and Gottlieb Bansemer, LNI:JJT, Oct. 16, 1918; Confidential Correspondence, 1913–24; ONI; RG 38; NAB.

3. Letter from Augustine Lonergan (U.S. House of Representatives) to the Office of the Judge Advocate General, Navy Department, Oct. 6, 1919; Confidential Correspondence, 1913–24; ONI; RG 38; NAB.

4. Monahan, Mary Agnes, Woman Yeoman 1st Class, List of Officers and Enlisted Men of the Regular Navy and the Naval Reserve Force Who Were Reported Dead or Missing During the Period 1917–19; Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, RG 45; NAB.

5. Muster Roll of the 1st Naval District ending 30 September 1918; Muster Rolls; Records of the Bureau of Navigation, RG 24; NAB.