When an American City Is Destroyed

The U.S. Military as First Responders to the San Francisco Earthquake a Century Ago

Spring 2006, Vol. 38, No. 1

By Rebecca Livingston

When a tsunami hits Indonesia, a flood drowns Haiti, or an earthquake strikes in Pakistan, the U.S. military is often the first to arrive with humanitarian aid and engineering expertise.

In this spring of 2006, it is a good time to remember the operations of the U.S. military during America's most famous of natural disasters—the San Francisco earthquake and fire of April 18, 1906.

Even though this disaster occurred 100 years ago, there are striking comparisons to modern-day relief efforts. The first responders in San Francisco and New Orleans faced similar challenges: people trapped in damaged buildings, looters, no drinking water, nonfunctioning hospitals, no utilities, no communcation, and no normal transportation systems.

Following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and the record-breaking hurricane season of 2005, we are especially aware of the importance of the military response during a natural or man-made disaster. Only the military has trained people, supplies, and a transportation and communication network ready to meet a mass catastrophe.

The 1906 California earthquake, the event that set the standard for horrific events, is often compared to modern disasters. As in the Katrina hurricane and levee failure, the San Francisco disaster was a two-pronged event, first a major earthquake, then a city-devastating fire.

National Archives and Records Administration holdings include extensive records relating to the 1906 earthquake, fire, and aftermath. This article will describe the textual military records that were forwarded to, or created in, the Washington, DC, military headquarters. Many other records remain at the National Archives Pacific Region (San Francisco) in San Bruno, California.

As in many natural disasters, the branches of the U.S. armed forces took great pride in their efforts and competed for the roles of the "first on the scene" or most valuable help or the organization that took charge during the disorder.

There were many heroes and leaders, but also some notable incompetents, looters, deserters, and drunkards. For anyone who wants to determine who was a hero, bungler, or villain, an examination of the official military records is a good place to start.

The issues of military versus civilian command, federal, state, or local responses to a metropolitan catastrophe have not yet been resolved in today's world. Seeing what worked and what did not work during the San Francisco earthquake could perhaps be helpful in the investigations of the first-response situations after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The military response in San Francisco also has valuable lessons for first response planning for future disasters.

When using the official military records, a note of caution is necessary. Some of the military reports include glowing success stories that contradict the suffering and disorder reported by newspapers or other sources. Some of the worst bunglers were the highest ranked military personnel who were the very same people who wrote the final reports. Official military reports have long passages describing the efforts of heroes, but finding the names of people who made disastrous decisions, such as those who contributed to the spread of the fire across the city, are lost in the bureaucracy. In some cases, names of genuine heroes were omitted from reports due to inter-service rivalry or professional jealousy.

The First Days

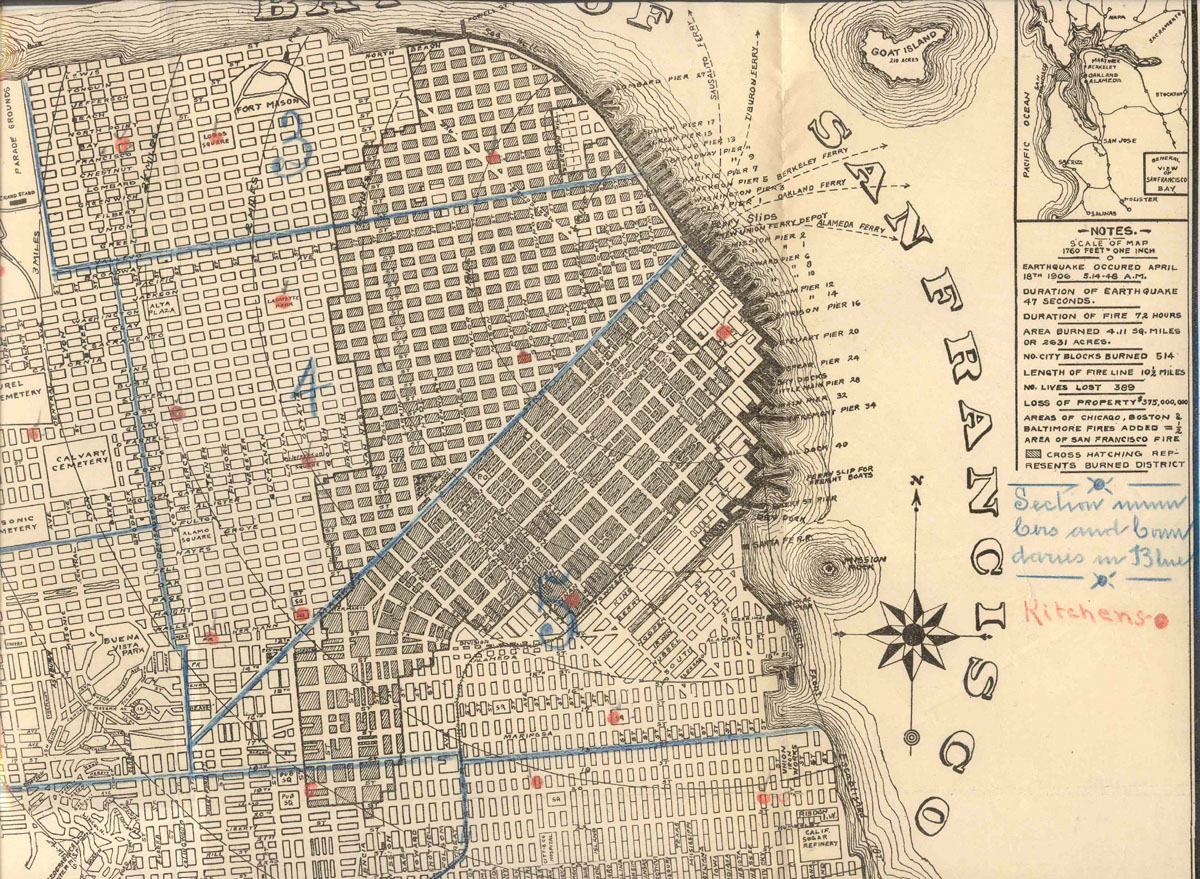

For San Francisco residents, many would say it was fortunate that the U.S. Navy, U.S. Army, U.S. Marine Corps, and Revenue Cutter Service had substantial forces already near the city. The Naval Training Station Mare Island, Marine Barracks Mare Island, Fort Mason, the Presidio, Benicia Barracks, Goat Island Torpedo School, Angel Island, Alcatraz Island, Letterman Army Hospital, and Naval Hospital Mare Island all had forces or supplies nearby ready to respond. The Army's Pacific Division and Department of California had its headquarters in San Francisco. There were Revenue Service cutters in San Francisco Bay and others in San Diego. Navy ships in the vicinity included USS Perry, USS Preble, receiving ship USS Independence, and USS Chicago (one day away in San Diego). USS Marion, a former U.S. Navy ship manned by the California Naval Militia, was also nearby.

Additional troops were stationed in Vancouver (Washington) Barracks, within easy call distance. It is less fortunate that both the Navy and the Army gave their old war horses, Civil War–era officers who were just waiting to retire, the plum jobs of commanding stations in San Francisco.

When the earthquake hit at 5:15 a.m on April 18, the military forces jumped into immediate action without waiting for instructions or authority from Washington, DC, the state government, or city authorities. American military forces, many on their own initiative, were on the streets of San Francisco minutes after the earthquake.

Although there was a great deal of confusion over who had authority in any particular operation, generally all parties agreed to settle the questions after first emergency operations were completed.

For example, the Revenue Cutter Service handed over its cutter Golden Gate to the U.S. Navy without question during the emergency but afterwards complained (all the way up to the President) that this had been an illegal action. In the first few days, the mayors, generals, and admirals worked side by side as did city firemen and civilians with soldiers, sailors, and Marines. USS Independence loaned its fire hoses and stretchers to the mayor of Vallejo shortly after the quake hit. USS Boston in San Diego, unable to communicate with the Pacific Squadron, stopped at Los Angeles at the request of the mayor of Los Angeles to pick up supplies donated by the chamber of commerce. The Navy turned over all its medical supplies to the Army without a thought to normal paperwork and accounting.

Although martial law was not declared by the President or the governor of California as was required by law, Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston, commander of Fort Mason, declared his forces commanded the city. His superior, Maj. Gen. Adolphus W. Greely, commanding the Pacific Division, was away from the city on leave when the earthquake hit. Within two hours of the earthquake striking, most of the troops at Fort Mason and the Presidio had reported to the mayor's office. These troops included the 10th, 29th, 38th, 65th, 67th, 70th, and 105th companies of the Coast Artillery and Troops I and K, 14th Cavalry. Funston assured the mayor that the troops would not encroach on city jurisdiction except when necessary. Medical personnel from the Naval Hospital Mare Island arrived in the city at 10:15 a.m. and started first aid immediately. Men of all ranks and services rushed into burning buildings to rescue people, guarded damaged buildings, and helped to restore order.

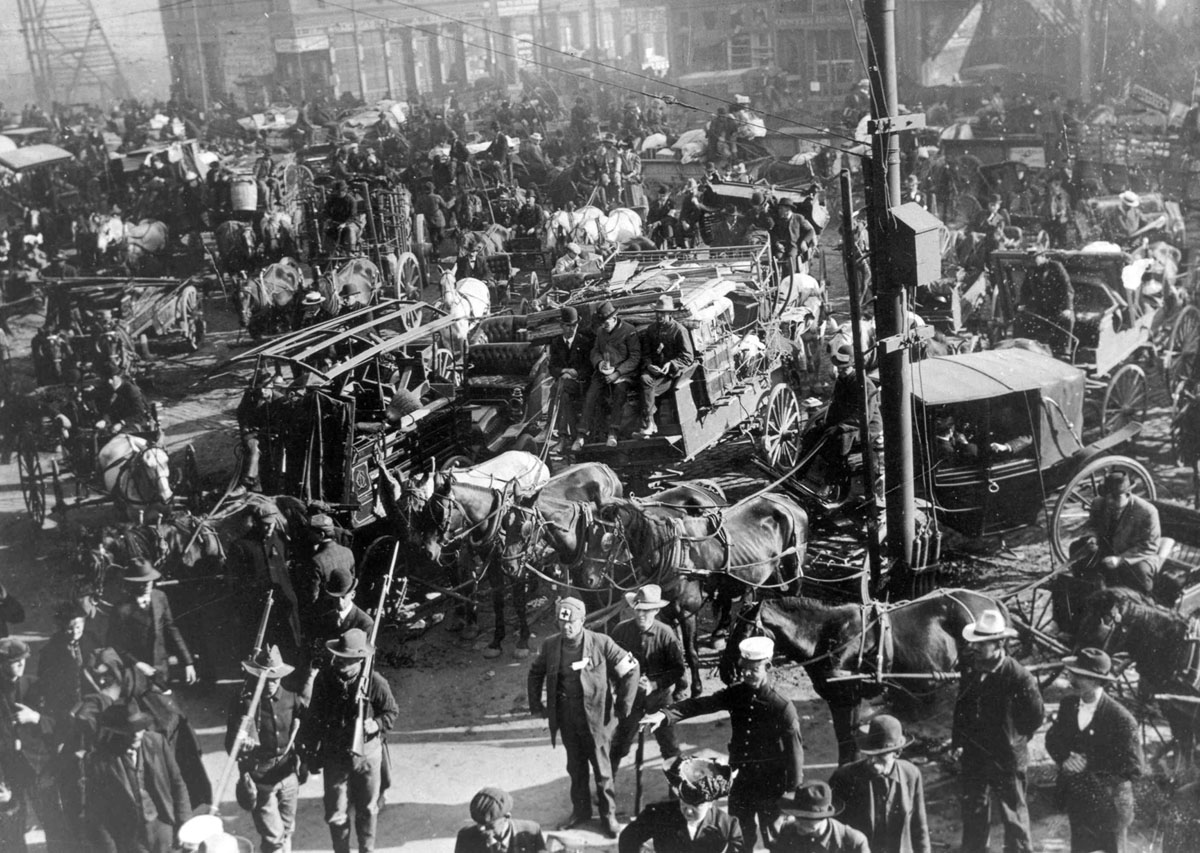

A quarter of a million people were on the streets, having escaped with only the clothes on their backs. Suddenly, both the rich and the poor were destitute. Ordinary people used to a comfortable living were now thirsty, hungry, dirty, homeless, and unable to find their family members. Even millionaires, their fortunes lost in the rubble, were homeless and without resources even to feed themselves. Funston wrote, "Its entire community of 450,000, deprived of all modern conveniences and necessities, had in forty-eight hours not only been relegated to conditions of primitive life, but were hampered by ruins and debris."

On the first day of the earthquake, General Funston knew that drinking water was going to be a major problem. There was no water in the entire city except Golden Gate Park. One of his first tasks was to get his engineers working on a backup water system with the Spring Valley Water Company. Meanwhile, the Navy brought drinking water and milk on ships for thirsty refugees.

Even on the first day, both the Navy and Army leaders began ordering blankets, tents, and food while they watched city and military warehouses burn to the ground. Within two days of the earthquake, portable latrines and tents were en route from many military storehouses from St. Louis, Missouri, Fort Snelling, Minnesota, and from around the country. Supplies intended for other naval stations, such as Guam, were rerouted and confiscated for San Francisco.

Most banks and the U.S. Mint in San Francisco were destroyed or shut down. One of the first duties of many of the military forces was to guard bank vaults and financial offices that were exposed to the elements and potential looters.

The entire telephone system in the city had been destroyed, and every telegraph office and station was gone. At first all messages were routed via the wireless system on USS Chicago and then to the outside world. On the morning of the quake, General Funston had to walk back to his headquarters from the city because he had no way to contact his troops at Fort Mason. Telegrams between Funston and the governor of California were seriously delayed and caused "mutual misapprehension as to our relations and attitude." It was the job of the U.S. Army Signal Corps to restore the telegraph and telephone lines, and from all accounts they did a spectacular job. By 10 a.m. on April 18, they established a military telegraph from the Presidio to military headquarters at Haight and Market Streets. With the help of the Signal Corps, Western Union opened offices on April 20, and by mid-May, communications had been restored to normal.

Another serious problem, as in Katrina, was the dislocation of families. General Funston wrote to the secretary of war that it was impossible to search for anyone, even for a senator's family or foreign service diplomats, because of the lack of communications. A postcard company suggested to the War Department that a million postcards should be purchased to distribute to survivors so they could contact their families and friends outside the city. (There is no indication that the War Department responded to this idea.) Some believed that it was an advantage to have military personnel replace city police and firemen because the military personnel did not have families or homes in the area that needed tending.

As happened after Hurricane Katrina, everyone in America wanted to help the refugees. The mayor of San Diego offered to receive 3,000 women and children. Crews of Navy ships and Navy retirement homes took up collections. The crew of USS Arkansas, for example, collected $90 for the Red Cross. Ironically, the citizens of New Orleans were among the first to offer help.

Both San Francisco in 1906 and New Orleans in 2005 were famous for being party towns with famous saloons, nightclubs, gambling, and music. In both cities, racial problems arose in connection with the distribution of food and supplies and especially the labor supply for clean-up projects.

Some complained to General Funston that Chinese people were excluded from the soup kitchens. He told the secretary of war that this was not true. He wrote that it was the consensus of opinion that the Chinese be served in separate relief camps. These camps were inspected by the Chinese legation from Washington.

The Japanese consulate complained that the lives of Japanese workers hired on construction jobs were being threatened by pro-union groups, including men from the mayor's office. Companies using Japanese laborers asked for military protection from violent union groups who believed the Japanese were taking the jobs of Americans.

White workers complained that Asians, taking jobs at lower wages, were lowering the wage scales. The mayor wanted companies involved in clearing debris to employ San Francisco residents at a fair wage, not to bring in workers (Asians) from outside. He wrote to General Greely, "[T]he extreme conditions that obtain here in San Francisco at this time should not be used as a means of reducing the price of labor."

After the first few days of cooperation among the military branches, city, and state officials, these relationships went downhill. Rear Adm. Bowman H. McCalla, commandant of the Mare Island Naval Station, and General Greely had a dispute about who had authority to give orders to the Marines. Although the Marines had reported themselves to General Funston at the beginning of the crisis, legally and historically they always served under the command of the Navy. McCalla wrote that Greely's complaints were "most extraordinary and very discourteous." Luckily, this dispute occurred in May, after the emergency response crisis. The Associated Press reported that Mayor Schmitz and General Funston were fighting; however, both refuted the charges to Secretary of War William H. Taft. (The Associated Press withdrew the story, at Taft's request.) Apparently, there were problems between the California National Guard and the regular army and naval forces. Each blamed the other for some sporadic looting.

Stories of Heroes and Rascals from Official Military Reports

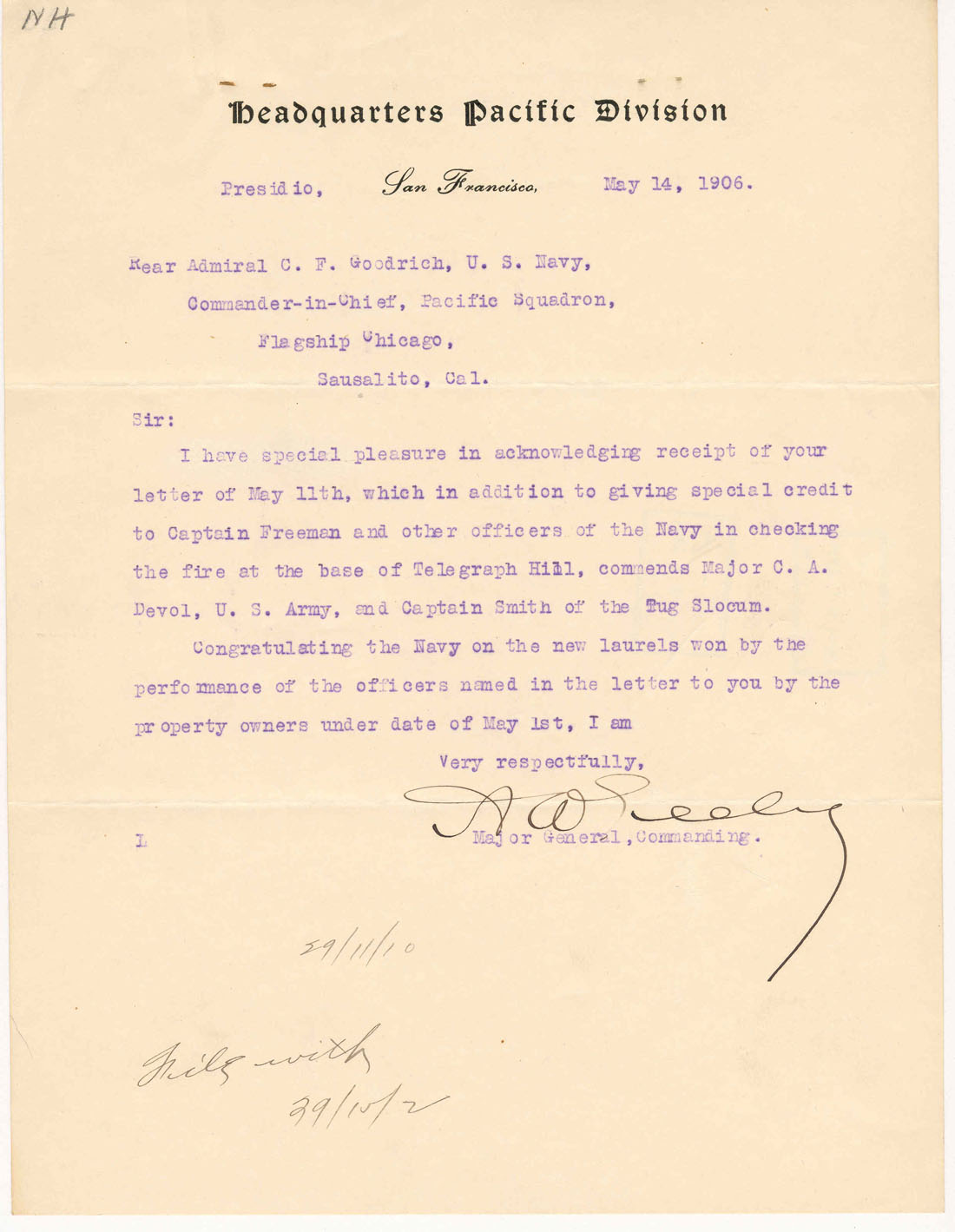

All of the official military reports are full of stories of individual heroism. Neither the Army nor the Navy was shy about glorifying its members. Multiple copies of thank-you letters from civilians or businesses were transmitted from one office or bureau to another with each office heartily endorsing the praise. Complaint letters, although far fewer in number, also appear in the military records. Here is a sample of some of the stories. They illustrate the importance of the actions of military personnel who rushed to help without regard to orders or military hierarchy in saving the city.

Navy Lt. Frederick Freeman

Lieutenant Freeman and his men from USS Preble were credited with preventing the fire from spreading to the wharves and financial district of the city. At 9 a.m. on April 18, Freeman took temporary command of USS Preble and proceeded from Mare Island to San Francisco, bringing all the surgeons and nurses from Mare Island Hospital.

Responding to requests from the city fire department, he ordered USS Preble and the fire tugs from the navy yard to send streams of water to shore. He and his men worked without rest for four days until they literally collapsed. Freeman received dozens of letters from the businesses of the city acknowledging his service. His name was left out of the Army reports (Greely's and Funston's) about the earthquake operations, presumably because he did a better job than his Army counterparts.

Marine Pvt. W. P. Bruton

Private Bruton was placed in charge of a dynamite party April 19–21, and "he did excellent work in this capacity, often risking his life in entering burning buildings and in fearlessly handling the explosives."

Navy Lt. Lucien Young

Lieutenant Young was in his apartment in the city when the earthquake hit. After helping the "ladies who had no male attendants" in his building, he placed himself on duty as "Naval Officer" and organized a special police to warn people of the approaching fire. He carried a number of women and children from the danger zone. In his own report, he stated he was never off his feet for three days and did not get to remove his shoes for four days.

Navy Capt. F. H. Holms (retired)

Captain Holms spent the first days after the earthquake searching for his seriously ill daughter in several hospitals that had to move their patients out of danger. Hearing that she had been moved to Mare Island, he went there and, after checking on his daughter, reported himself to Adm. C. F. Goodrich, commander of the Pacific Squadron. Despite being retired, he organized the neighborhood men for fire protection and self-defense and donated three vacant apartments he owned for refugee families.

Marine Lt. Fred A. Udell

Lieutenant Udell was a patient at Naval Hospital Mare Island suffering with Bright's disease (kidney disease). When the earthquake hit, he jumped out of his bed and headed to San Francisco. For two days he put out fires, rescued people, and guarded a bank from looters. After the city was under control, he returned to his hospital bed. In June 1906 he was retired on disability because of the seriousness of his kidney disease.

Marine Lt. John H. White

Lieutenant White was a court-martial prisoner at Mare Island Marine Corps Barracks awaiting trial for charges of drunkenness and profane language. When the earthquake hit, he was released from arrest for emergency relief service. He performed so well that the charges were dropped against him on April 21, 1906. Nevertheless, he received a stern letter that warned him not to take advantage of the situation and that further drunkenness would not be tolerated.

Navy Lt. E. H. Dunne

Lieutenant Dunne was arrested for drunkenness on April 25 on board USS Independence and was suspended from duty for three days.

Apprentice Seaman Albert J. Cappallo

Apprentice seaman Cappallo was drunk on duty on April 22 while on sentry duty at Pier 21.

Coal Heaver Meyer Katz

Meyer Katz was a civilian who worked alongside Revenue Cutter Service personnel pulling people from burning buildings. Mr. Katz went into a burning building to rescue a goat. On April 26, he enlisted on board the Revenue Cutter Thetis with his goat. (The goat later became a mascot for the USRC Perry.)

Revenue Cutter Boatswain W. Hallberg

Boatswain Hallberg arrested a deputy sheriff for carelessly discharging his firearm and encouraging citizens to loot. He took the deputy's star and pistol away from the drunk man, but "he had to be turned loose because they was surrounded by fire."

Captain Bowers

A man in a Navy uniform, claiming to be "Captain Bowers," stole an automobile belonging to Mrs. Thomas H. Grant, secretary of the Red Cross of California. She reported her "machine" was last seen at Market and Larkin Streets. The Navy Department was unable to identify a captain by this name. Admiral Goodrich complained to General Funston that the Navy was being blamed for actions of persons wearing uniforms that looked like naval uniforms.

Chief Electrician Joseph A. Curtin

After assisting the dynamite party, Chief Curtin of USS Pike took possession of a church for emergency medical treatment, hunted up physicians and nurses, and secured beddings, medicines, and food. The church was named "Curtin Hospital" and treated 75–150 patients daily. The hospital later became permanent, and city public health officials, who wanted to name the hospital after a hero from the California National Guard, argued with the Navy about the name of the hospital. (The Navy won this fight, and the hospital remained the "Curtin Hospital.")

Navy Surgeon Victor C. B. Means

Surgeon Means waited at the Cosmos Club from the time of the earthquake until April 25. He stated he was waiting for someone to give him orders. In the meantime, he did not offer aid to any person. The Navy Department considered this response unacceptable, and Surgeon Means was dismissed from the service.

Capt. Leonard D. Wildman

Captain Wildman, Chief Signal Officer of the Department of California, led efforts to restore communications in the city. He took his office's important papers to his hotel room for safety, and when that site became dangerous, he commandeered a whisky wagon to save them. He won high praise for restoring the telephone and telegraph lines in the city within days of the earthquake.

Chief Gunner's Mate A. D. Freshman and Crew of USS Fortune

Freshman organized a relief party from USS Fortune and the "men of the submarines" to collect food from naval crews in the area to give to the 1,800 refugees who were transported from San Francisco to Oakland on board USS Fortune on April 19, 1906. The 30-gallon coffeepot on board the galley of USS Fortune was constantly refilled to serve to the refugees. On April 24, USS Fortune delivered 1,800 gallons of milk to the Presidio for refugees.

Marine Pvt. Michael English

On May 6, 1906, Private English was sentenced to six months in prison for being under the influence of alcohol and absent without leave while a member of a landing party to help protect the lives in the recent catastrophe.

Army Privates Frank P. McGurty, William Zeigler, and Henry Johnson

These three privates of Company E, 22nd Infantry, separated from their command, helped 3,000 destitute Italians, Japanese, and Chinese on Jones Street. They stopped looting and opened a bakery. They worked day and night caring for the refugees and distributed food, tents, and shoes and established a camp of shacks for temporary shelter.

NARA invites researchers to examine the voluminous original files for themselves. The answers to questions about disaster planning, command hierarchy, communications, and logistics for a successful response to a natural disaster are complicated matters that call for a closer scrutiny of what happened in San Francisco 100 years ago. Here are descriptions of the military records relating to the disaster that are held in the National Archives Building in Washington, DC.

Navy Records

Record Group 45, Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, includes several historical collections with records about the actions of U.S. Navy people and ships during the earthquake and fire. The U.S. Navy Subject File, 1775–1910, file "OO-Operations of Fleets," includes reports from the naval ships that participated in the relief activities and reports of Lt. Frederick Freeman and other officers on shore patrol. There are also some letters of gratitude from city businesses. The file "NH-Honors" includes many more letters of appreciation from San Francisco banks, wine companies, and warehouse owners who credited the Navy with extinguishing the fires. The U.S. Navy Area File, 1775–1910, Area 9, April 18–May 1906, includes reports from the ship captains on USS Chicago, USS Fortune, USS Boston, and others relating to the operations. There are many telegrams relating to ships' movements and orders. There are also reports detailing the communication problems among the ships and stations due to earthquake damage. The Area File is available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M625.

Record Group 125, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Navy) includes the records of proceedings of naval and Marine Corps officers' promotion and retirement boards. Letters of commendation or complaint are with these board records. The board records also include the officer's monthly fitness reports, which show where the officer was stationed for the month with evaluations about his performance from his commanding officer. There are promotion/retirement board records for Lt. Frederick Freeman, Rear Adm. Bowman H. McCalla, Lt. John E. Pond, Lt. Lucian Young, Marine Lt. Fred A. Udell, and most of the other naval and marine officers who participated in the fire-fighting and relief efforts.

Record Group 125 also includes the records of proceedings of U.S. Navy courts of inquiry and courts-martial. The trial transcripts for sailors and Marines who were accused of drunkenness or absence without leave during the relief operations are in these records.

Record Group 80, General Records of the Navy Department, includes Office of the Secretary of the Navy correspondence, 1897–1915, file number 21780. This file includes two photographs of San Francisco showing the destruction of the city. There is also correspondence mostly about the procurement, delivery, and distribution of relief supplies.

Record Group 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, includes the general correspondence of the Bureau of Navigation, 1903–1913. File 2295/35 to 2295/170 is a consolidated collection of San Francisco–related records. It includes orders to officers and ship movements. It includes many letters of praise for naval personnel, mostly from within the Navy Department. In response to a circular letter asking for lists of persons who performed extraordinary duty, commanding officers sent in hundreds of names. These lists show that many sailors and Marines away from their regular command reported themselves to city or army officials on their own initiative. There also are some reports of investigation of persons who had not sufficiently performed their duties.

Record Group 24 also includes U.S. Navy logbooks (see Firsthand Reports sidebar). These hourly accounts are very helpful to place events in time perspective. They document who left the ship, supplies delivered, refugees temporarily housed, and fire-fighting activities. Some of the pertinent logbooks are from USS Perry, Preble, Independence, Chicago, Fortune, and Boston.

In Record Group 52, Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, there is consolidated general correspondence, 1897–1925, file number 103882, relating to the earthquake and fire. This file includes a note from Secretary of the Navy Charles J. Bonaparte urging complete cooperation with the Army. It includes the reports of medical officers at the Naval Hospital Mare Island who treated civilian refugees and injured city firemen. It also includes reports of naval surgeons who went on shore duty to provide medical care in the city. Record Group 52 also includes a medical logbook of the Naval Hospital Mare Island, April–May 1906.

Revenue Cutter Service

In Record Group 26, Records of the U.S. Coast Guard, correspondence of the Revenue Cutter Service has a consolidated file on the San Francisco earthquake and fire. This file includes reports from the captains on the revenue cutters who responded to the disaster and reports of personnel who participated in fire-fighting activities. The logs of Revenue Cutters Thetis, Golden Gate, Perry, Bear, and McCullough have hour-by-hour accounts of the events near San Francisco. (See sidebar)

U.S. Marine Corps Records

Record Group 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, includes a consolidated correspondence file relating to San Francisco in the general correspondence, 1904–1912, file number 16811. This file includes the report of Capt. A. T. Marix, commander of the Marine Barracks Naval Training Station San Francisco, and Lt. Col. Lincoln Karmany, commander of the Marine Detachment, Mare Island. According to the reports, Marines from USS Independence and raw recruits from the Marine Barracks at Mare Island arrived at Fort Mason at 7:30 a.m. on the day of the earthquake and reported to General Funston for duties in the city. This file includes letters of thanks from protected businesses and newspapers in San Francisco and from Army officials in the Pacific Division. The Marine Corps' Historical Division includes letters received, 1906. The Marine Corps muster rolls, Mare Island Barracks, USS Independence, and other units near San Francisco include the names of officers and enlisted men who participated in the relief operations.

Army Records

In Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, there is a consolidated correspondence file in the general correspondence, 1890–1917, file number 1121191, relating to the San Francisco operations. This large file includes casualty lists of civilians and military; correspondence among the secretary of war, General Greely, and the governor of California; a map showing the areas of the city hit by the fire; claims from civilians for liquor and tobacco destroyed by the Army; orders for moving regiments; and Greely's final report relating to the earthquake and fire operations.

Also in Record Group 94 are consolidated correspondence files for the Army officers who participated in San Francisco operations. These correspondence files, which are similar to personnel files, include commendations and evaluations. Some officers' files (e.g., Greely's) are filed with Commission Branch correspondence. Others are with the Appointment Commission and Personal Branch or with the Adjutant General's Document file.

In Record Group 107, Records of the Secretary of War, there is a subject file in the general correspondence, 1890–1913, called "San Francisco earthquake." This file includes the reports and telegrams received by Secretary of War William Howard Taft. There are some American Red Cross references because Secretary Taft was the president of the Red Cross.

In Record Group 393, Records of U.S. Army Continental Commands, the Department of California records include correspondence relating to the San Francisco fire. This file is mostly about the transportation and delivery of food, water, blankets, tents, and other relief supplies. The Pacific Division records include many letters from civilians asking the Army to search for lost relatives. There is a set of outgoing telegrams issued by the Pacific Division and records of the Oakland Relief Committee. There are also lists of subsistence stores, some of which show fire damage. Within the Pacific Division records, there is correspondence and reports of the Bureau of Consolidated Relief Stations, 1906, the organization that directed the relief camps.

In Record Group 77, Records of the Office of the Corps of Engineers, in the general correspondence 1894–1923, there is consolidated file number 59169. This file includes the report of Capt. M. L. Walker commanding companies C and D, First Battalion of Engineers. He reported that he woke up during the earthquake and, believing it was minor, went back to sleep. About 6:45 he was awakened again, this time by a civilian carrying orders from General Funston. By 7:15 a.m., his troops had reported to Mayor Eugene E. Schmitz. Instructed by the mayor, Walker's engineers guarded banks to prevent looting and halted civilians from running into burning buildings. The next day, they were ordered to sanitary duty in connection with the refugee camps. On April 20, the engineers assisted the naval forces in fire control and designed systems to get salt water to the fire engines. Later they demolished damaged buildings, a dangerous job due to the likelihood of falling beams and bricks.

The file also includes the report of Capt. William W. Hunt, Chief Engineer Pacific Division, who submitted plans for portable temporary houses that would house eight families, with each family having two rooms and a shower and water closet to share. (The estimated materials and labor cost for these homes was $681 each.)

In Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, general correspondence, 1890–1914, consolidated file number 227290 includes some of the earliest telegrams after the earthquake. Most of this very large file relates to the movement of supplies from around the country to San Francisco. There are also photographs and blueprints for Army buildings that needed to be rebuilt. Anyone interested in planning for modern-day disasters may want to read about all the details of the 100-year-old disaster. It appears that huge quantities of supplies arrived relatively quickly, mostly by rail or army steamers. The first shipments to arrive at the depots were attacked by desperate civilians and looters. Full loads got through only when the Army learned to guard them and have military personnel distribute supplies in an orderly fashion.

In Record Group 111, Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, document file 1897–1917, file number 16437, is a consolidated file on the earthquake. It includes reports of the Signal Corps about building a new communication system for the city.

It is clear from the examination of military records at the National Archives that the successful emergency response to the San Francisco earthquake and fire was dependant on military heroes who temporarily ignored the military and civilian command structure, bureaucracy, and delays by jumping into dangerous rescue situations. These heroes, people who were willing to rush into burning buildings and work tirelessly and efficiently and to take command, made a tremendous difference in the relief efforts during the first few days of the crisis. Their military training and ready access to supply, communication, and transportation systems allowed the military to perform faster and in ways impossible for civilians.

As General Greely wrote in his final report, "The services of the army in San Francisco is a unique page in military history. Despite the strict professional training of the United States Army, it has shown unexpected powers of adaptability to unprecedented and difficult conditions. Accustomed to supreme commands, it has known in a great calamity how to subordinate itself for an important civic duty—the relief of the destitute and homeless. Thrown into intimate relationships with the State and municipal authorities, serving side by side with the National Guard and the police department of San Francisco, cooperating with the great civil organizations of the Red Cross, its operations were free from violence, from quarrels and even bickering."

Rebecca Livingston is an archivist with Old Military and Civil Records at the National Archives. She is the senior specialist in pre–World War II U.S. Navy records. In Prologue, she has previously written about researching Spanish-American War veterans (Spring 1998) and blockade-runners during the Civil War (Fall 1999). She completed undergraduate and graduate work at the University of Maryland.

Find out more: