A Founding Father in Dissent

Elbridge Gerry Helped Inspire Bill of Rights in His Opposition to the Constitution

Summer 2006, Vol. 38, No. 2

By Greg Bradsher

During his second term as governor of Massachusetts, in 1811, Elbridge Gerry, upset with the Federalist Party's outspoken opposition to President James Madison's foreign policy, approved a controversial redistricting plan designed to give the Republican Party an advantage in the state senatorial elections.

The Federalist press responded to this plan with cartoon figures of a salamander-shaped election district—the "Gerrymander"—a term still used to connote an irregularly shaped district created by legislative fiat to benefit a particular party, politician, or other group.

Gerry would be rewarded by the Republicans for his staunch support by being elected in 1812 as Madison's Vice President.

In late 1814, the 70-year-old Gerry died in office. He was buried in Washington, DC.'s Congressional Cemetery, and Congress erected a monument over his grave. This monument, the first done at the nation's expense, contained the words that Gerry spoke and tried to live by: "It is the duty of every man, though he may have but one day to live, to devote that day to the good of his country."

Today, as well as for the at least the last 150 years, most Americans have never heard of Elbridge Gerry, though many have heard the term "gerrymander." This undoubtedly would have disappointed him.

Like many of the other Founding Fathers, he was concerned about his legacy, the fame that would be attached to individual leaders of the Revolutionary generation. His friend John Adams believed that this fame would depend, to a large degree, upon the view that future generations held about the American Revolution and the Constitution. Those future generations have, for the most part, looked favorably on the documents that the Founding Fathers created and under which we live. But the founders and their specific views, with a few exceptions, are little known or appreciated. History—what is written about the past—has a way of simplifying things, and in the process important and interesting details are lost.

This is especially and unfortunately so of the work of the drafters of the Constitution. We all know about the Supreme Court trying to determine "original intent," but few of us know anything about the actual views held and put forth by the drafters, and the compromises they made, to achieve the system of government that would be effective, preserve order, secure property, and protect the liberties that had been won as a result of the American Revolution.

By understanding the views held by the framers of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, we all can be better able to form our own political views about the best means of securing our own life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness. Elbridge Gerry is a good starting point for such an understanding, because like his contemporaries, he shared the view that the Constitution they drafted was not perfect and the government created under it would have to be carefully nourished and watched.

Gerry, born in Marblehead, Massachusetts, on July 17, 1744, to a wealthy family, received his academic training at Harvard and his political training from his mentor, Samuel Adams. During the early 1770s he served in the colonial and Revolutionary legislatures, and during the American War for Independence, he served in the Continental Congress (1775–1780 and 1783–1785), where he signed the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. After the war, he continued to serve in Congress until 1785, when he married and settled down to domestic life in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His absence from political life was short-lived, as in the wake of Shays's Rebellion in western Massachusetts in 1786 he was selected to attend a convention in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation.

Gerry arrived in Philadelphia on May 29, 1787, several weeks after the deliberations had already begun. It is probable that some of his colleagues did not welcome his arrival. He had demonstrated during his years in Congress that he could be trying and impractical. These character traits were part and parcel of his idealism and his classical republican mind that made him anti-monarchy, anti-military, and anti-party.

He came to the convention ready to give the central government greater authority, being "fully convinced that to preserve the union, an efficient government was indispensably necessary." Yet he did not want the central government to be too powerful, as it would open the door for despotism. He desired a form of government that would find a balance between too much power and too much liberty, between monarchy and democracy. Such a government, he believed, should be based upon republican principles, where power would be divided wherever possible and where too much power would not be placed in the hands of a single person, group, or branch of government.

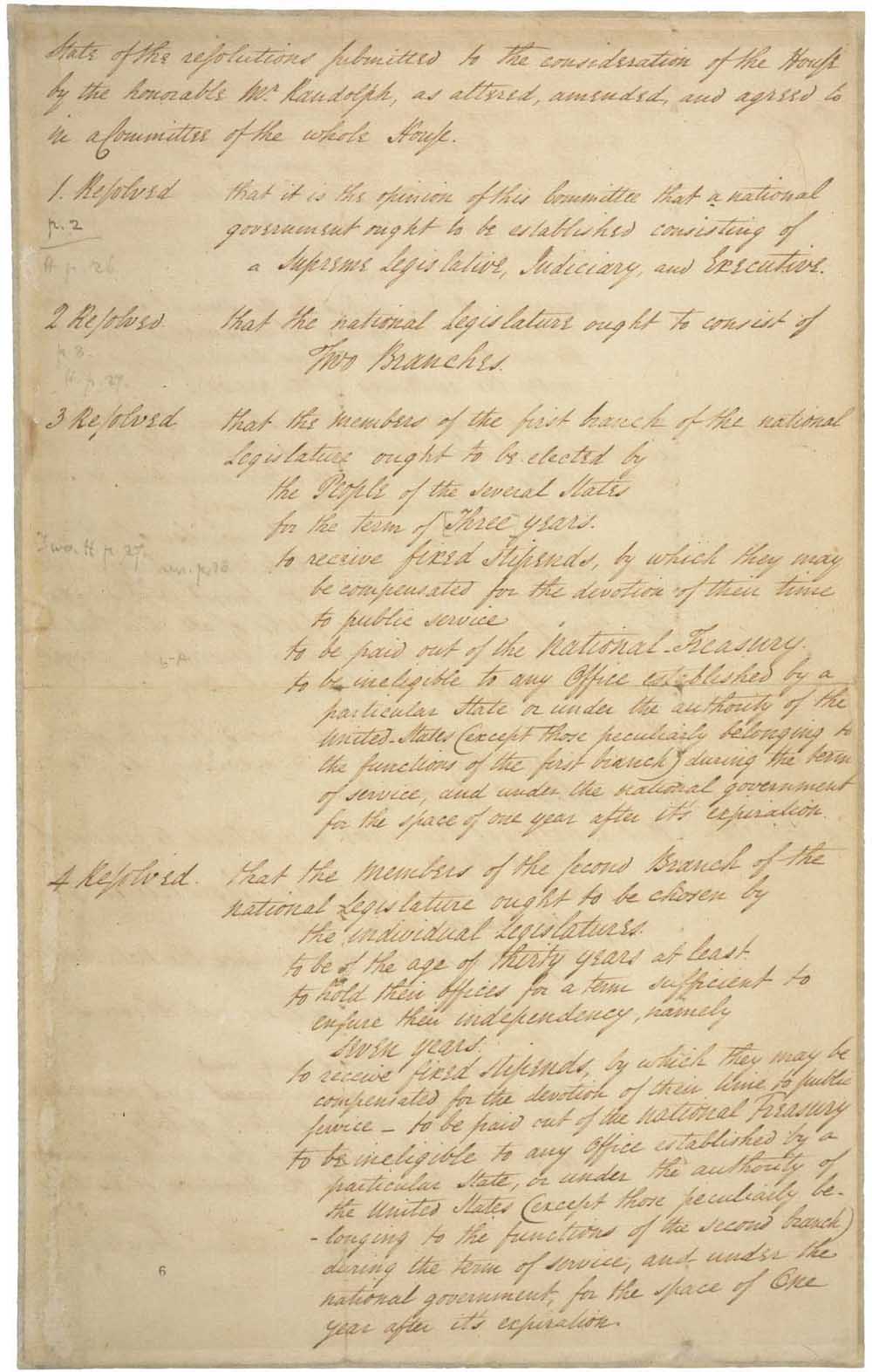

His first day in attendance found the members of the Convention discussing doing away with the Articles of Confederation and adopting an instrument that would create a new national government. At the first opportunity that day Gerry questioned the legality of doing more than just revising the Articles of Confederation.

Despite his arguments, two days later the Convention voted to proceed to discuss the Virginia Plan, which provided for creating a new, stronger central government.

Gerry very quickly found himself in the middle, between the states' righters who wanted the balance of power to remain with the states and the nationalists who wanted to create a powerful central government. Because of his desire for a stronger central government, Gerry frequently sided with the nationalists, but always tempering his support by insisting that federal features be retained in any new system of government and urging that republican principles be adopted.

During June he frequently helped to check the extreme nationalists by arguing and voting against their motions. He forced them to yield on an absolute veto for the chief executive and on giving the central government an absolute power to negate state laws and got them to drop the word "national" out of the Virginia Plan and substitute the phrase "the United States." He also took to the offensive by proposing and supporting various motions, many of them relating to elections, which he maintained should be frequent.

Because of his fear of demagoguery and belief the people could be easily misled, he advocated indirect elections. Although he was unsuccessful in obtaining them for the lower house, he did obtain such elections for the Senate, whose members were to be elected by the state legislatures. He made numerous proposals for indirect elections of the chief executive, most of them involving the state governors and electors. He was also active in supporting an amendment provision, believing that "the novelty and difficulty of the experiment requires periodical revision." Agreeing, the Convention adopted such a provision.

The critical issue facing Gerry and the Convention in June was the relationship of the central government to the states. By the end of the month, the Convention was on the verge of collapse as a result of the members being unable to resolve this issue. During the last days of June and first of July, Gerry continually called for compromise.

On July 2, after a deadlock vote on whether the states would be equally represented in the Senate, Gerry stated "We must make concessions on both sides" because "accommodation is absolutely necessary, and defects may be amended by a future convention."

If the Convention failed, he told his colleagues, "we shall not only disappoint America, but the rest of the world."

Agreeing that a compromise was needed, a committee was appointed to produce one, and Gerry was appointed its chairman. During the committee discussions, he was willing to compromise on certain issues, such as equal representation in the Senate, in order to save the Convention from collapse. But on other issues, such as prohibiting the Senate from originating money bills, a motion he had earlier unsuccessfully offered, he was unwilling to compromise.

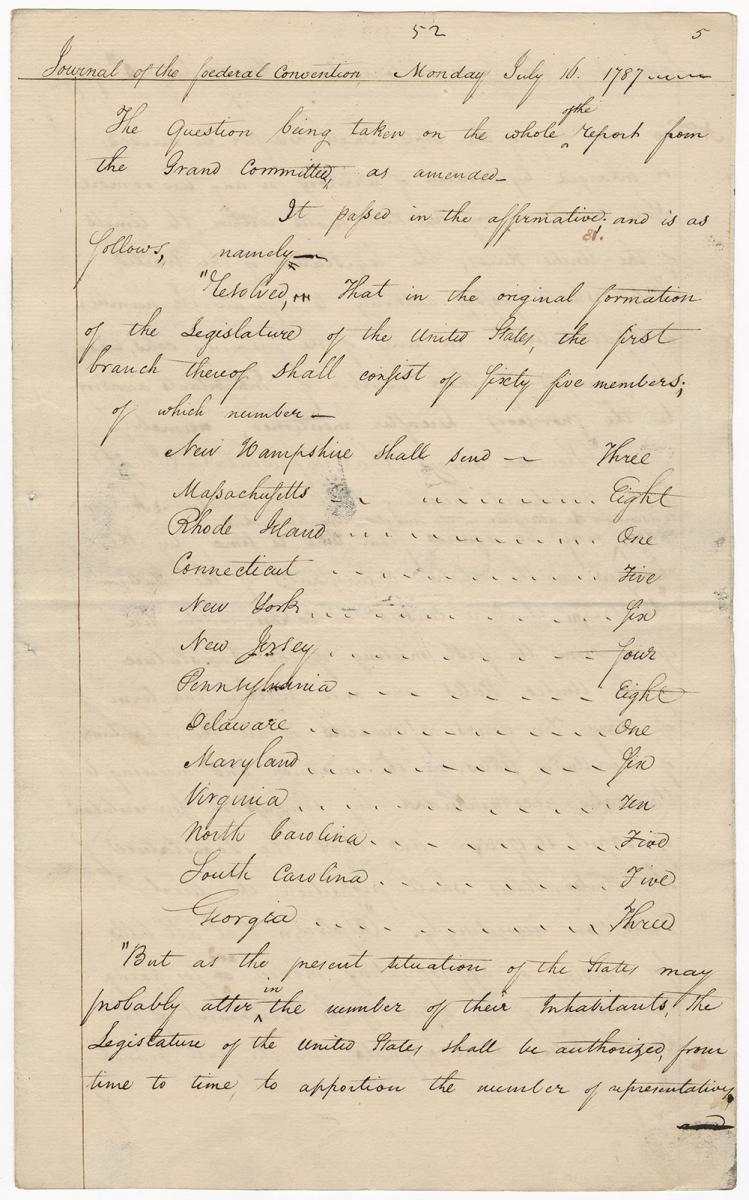

A compromise was finally achieved, which among other things, provided for proportional representation in the lower house and equal representation in the Senate and provided that the lower house would raise revenue and appropriate money. After presenting the committee's report, Gerry told the Convention that although he had some objections to it, compromise was needed if the Convention was to avoid collapsing and quite possibly, to prevent the Confederation from dissolving.

"If we do not come to some agreement among ourselves," he maintained, "some foreign sword will probably do the work for us." Addressing the central government-state relationship, he informed his colleagues, "We were neither the same Nation nor different Nations. . . . We ought not therefore pursue the one or the other of these ideas too closely." He argued that the committee compromise provided the best solution, a government that would be "partly national, partly federal."

On July 15, after 10 days of debate on the report, during which Gerry continually called for compromise, it was put to a vote. It passed by a 5-4 margin. In calling for compromise, chairing the committee, asking the Convention to accept the "Great Compromise," and voting for it, Gerry played a crucial role in saving the Convention at its critical point.

Once the report was accepted, the Convention got down to working out the details relating to the powers to be granted to the central government, the jurisdiction of the judiciary, and the election of the President. From July 17 to 26, Gerry made 29 speeches on these issues, two-thirds of them on the powers and election of the executive branch. Although fearing one-man rule, he opposed the executive being too dependent upon another branch of government. He opposed the idea of direct elections, believing the people could be easily misled by a few designing men or manipulated by certain groups.

He also opposed the idea of Congress electing the President, as he would be dependent upon that body. What he preferred was letting the governors do the electing, or letting them do the selecting of electors, who would elect the President. When the Convention seemed determined to have Congress do the electing, Gerry successfully got motions adopted that would allow the President to serve a relatively long term and be ineligible for reelection, making him less likely to be dependent on Congress.

Like the other members, Gerry assumed that Washington would be the first President. But that did not prevent him from calling for impeachment provisions. "A good magistrate," he maintained, "will not fear them," and "a bad one ought to be kept in fear of them." He also expressed his hope that "maxim would never be adopted here that the chief magistrate can do no wrong." Agreeing, the Convention adopted an impeachment provision.

Gerry was also successful in getting the Convention to kill the idea of blending together the executive and members of the judiciary into a council of revision to review legislation, something the nationalists desired because of their fear of legislative supremacy. Gerry called such a council an "improper coalition," violating the principles of separation of powers, and reminded the Convention that the representatives were the best guardians of the people's rights and interests.

In one other area Gerry was successful in getting the Convention to accept his views. This was the manner in which senators voted. On July 23, Gerry, in keeping with his promise to support the "Great Compromise," did not object to the principle of equal representation in the Senate and voted to give each state two senators. But he did move that the senators vote as individuals, which would mean if the senators split their votes, a state would lose its status of equality within the Senate. Up to this point it was assumed that the senators would cast their votes as a unit, as had been done in the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Convention itself. His novel idea was appealing to many and was adopted.

During the latter part of July, sentiment was growing to prepare a draft constitution to summarize what had been decided on a piecemeal basis during the preceding two months. So, at Gerry's prompting a committee was appointed for that purpose. In early August, when Gerry saw the draft, he believed it contained too many anti-republican principles, with the central government being made too powerful, the liberties of the people threatened, and the sovereignty of the states subverted. Thus, during the remaining six weeks of the Convention he attempted to correct as many perceived shortcomings in the proposed constitution as he could, constantly reminding his colleagues, as he had before, that the document they produced would not be ratified unless it was acceptable to the people.

During those weeks Gerry was one of the most active participants, making 78 speeches, most of them relating to the powers of the central government. He successfully got motions passed prohibiting Congress from passing bills of attainder and ex post facto laws, but he was unsuccessful in urging frequent elections and prohibiting plural office holding.

Of all the powers given to the central government, Gerry most feared the military power, a view shared by many of his contemporaries. Continually he offered motions to limit the military power and to prevent conditions that could lead to military despotism. He was successful in getting the Convention to limit the power of the central government to send military forces into the states and empowering the chief executive only to "make war" but not "declare war." He also successfully fought off attempts by the nationalists to give the central government total control over the state militias. He was, however, unsuccessful in preventing a peacetime standing army or limiting it to a size of no more than 3,000 soldiers.

By the end of August, Gerry, fearing the proposed constitution threatened the liberties of the people and the rights of the states, concerned about the health of his wife and infant daughter, as well as tired and frustrated by the Convention debates, contemplated leaving the Convention as others had and would do. But he decided to stay so that no one could later charge he attempted to break up the Convention and so he could correct as many defects as he could.

During the first week of September, he spoke frequently on limiting the military power, the manner of electing the President, checking the power of the chief executive, and against having a Vice President, especially one who was to be the president of the Senate. The latter provision he maintained violated the principles of separation of powers. "We might as well put the President himself at the head of the Legislature," he had argued on September 7. "The close intimacy that must subsist between the president and vice president makes it absolutely improper." His colleagues were not persuaded. In fact, all of his motions were rejected, as most members were satisfied with the document they had created. Ironically, a quarter of century later, Gerry would be Madison's Vice President and die on the way to preside over the Senate.

Despite his setbacks during the first week of September, Gerry continued during the second week calling for reconsideration of certain provisions. One of the most important to him was the ratification provision. Having previously questioned the propriety and legality of dissolving the Confederation without referring the constitution to the Confederation Congress for approval, he again raised that point and objected to the requirement that only nine states, not all, were needed for ratification. When his motion for unanimous consent was defeated, Gerry turned his attention to measures to protect individual rights and to curtail the power of the central government. On September 12, believing there was nothing else he could do to stop the proposed constitution from being adopted by the Convention, he moved that a national bill of rights be incorporated into it. He was seconded by George Mason. When his motion was rejected, Gerry unsuccessfully offered numerous specific provisions to guarantee individual liberties.

On September 15, after the members had gone over the final draft, Edmund Randolph, Mason, and Gerry spoke in opposition to the proposed constitution. Gerry, after detailing his minor objections, told the Convention that he could live with them if individual rights had not been rendered insecure by the power of the government to make laws it may call necessary and proper, to raise armies and money without limit, and to establish tribunals without juries. He then joined Mason and Randolph in calling for a second constitutional convention where measures could be adopted to adequately protect individual rights.

Two days later Gerry addressed the Convention for the 153rd and last time. After giving his objections to the proposed constitution, he stated he could not sign the document. Then he watched as 39 men affixed their signatures to the document. It must have been distressing to him, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation, not to sign. But it was even more distressing to think about the document itself, containing so many things he opposed and not including so many things he believed it should. Nevertheless, it must have pleased him to see that many of his motions and beliefs that protected the rights of citizens and the sovereignty of the states had been incorporated into the document and that he had been able to check many of the excesses of the extreme nationalists, thereby preventing the establishment of an even more powerful government.

Gerry, although believing the constitution being sent to the states for ratification contained too many provisions that were inconsistent with republican principles, was reluctant to take an extreme stand against its ratification. He was afraid that if the ratification debate was too acrimonious, it would create conditions favoring social instability and quite possibly civil war and disunion. Thus, once the ratification process began, he dropped his call for a second convention, believing the best course would be to favor the constitution with amendments.

In October he wrote the Massachusetts legislature that "it was painful for me, on a subject of such national importance, to differ from the respectable members who signed the constitution. But conceiving as I did that the liberties of America were not secured by the system, it was my duty to oppose it." In this letter he gave his specific reasons for not signing, stressing the lack of any national bill of rights and the fact that the government was national, not federal in composition. If the people adopted the document as it stood, he maintained, they were in danger of losing their liberties. But, if they rejected it altogether, "anarchy may ensue." "In many respects," he wrote, "I think it has great merit, and by proper amendments, may be adapted to the 'exigencies of Government' and preservation of liberty." He concluded the letter by pledging to "support that which is finally adopted."

The Massachusetts convention on February 7, 1788, by a 187-167 vote, ratified the Constitution with recommendatory amendments, many of them relating to a national bill of rights. Before this convention, none of the states had requested amendments. After it, all but one ratified the Constitution and proposed amendments at the same time. This must have pleased Gerry, as it was he who had first made the suggestion to the Massachusetts convention as well as suggesting specific amendments.

Once the Constitution was ratified, Gerry kept his word about supporting it, and agreed, once elected, to serve in the first House of Representatives. After his election, he wrote a friend that many members of the First Congress would consider him an enemy of the Constitution, but he maintained nothing was more "remote from truth."

"Since the commencement of the revolution," he wrote, "I have been ever solicitous for an efficient federal government, conceiving that without it we must be a divided and unhappy people." But he never wanted extremes, desiring a government "that should possess power sufficient for the welfare of the union" but balanced "to secure the governed from the rapacity and domination of lawless and insolent ambition." He stated he wanted amendments before ratification, but since that had not been the case, he would support the Constitution and hoped amendments would be adopted that "will remove just apprehensions."

Gerry arrived at Congress in the spring of 1789 ready to see that the proposed amendments were given due consideration and to ensure the Constitution was implemented and administered so as to protect the liberties of the people. He also desired to raise issues, such as the location of the seat of government and the assumption of the national and state war debts, that he had first brought up at the Constitutional Convention but which had been deferred to the First Congress.

The First Federal Congress established many of the government's major institutions and policies, including setting up the executive department and judiciary system, and recommending a national bill of rights. Gerry, who had spoken the sixth most times at the Constitutional Convention, was an active participant, especially during the first five-month session, speaking more times than any other member save James Madison. Setting forth the same themes he had expounded at the Constitutional Convention, Gerry hoped the national government would find a true balance between liberty and power. He continually worked to protect the liberties of the people and the rights of the states. Avoiding political party affiliation, he preached the politics of conciliation and republicanism.

In 1793, after two terms in Congress and tired of the political factions then evolving, Gerry retired from public service. But his retirement was only temporary. During the following 20 years he would serve on a diplomatic mission to France, two terms as governor of Massachusetts, and as Vice President. During those years, Gerry continually attempted to restore his country to the idealism, virtue, patriotism, and revolutionary republicanism of the early days of the American Revolution. During his 40 years of public service, Gerry made many enemies, yet very few questioned his motives and sincerity. William Pierce, at the Constitutional Convention, wrote that Gerry's "character is marked for integrity and perseverance" and that he "cherishes as his first virtue, a love for his country."

Today, Gerry is all but forgotten, yet his presence (which was often a nuisance to his colleagues), persistence, and political skills were important factors in shaping the system of government under which we live. He certainly deserves remembering. And indirectly he is.

When visitors to the Rotunda of the National Archives view the Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation, Constitution, and Bill of Rights, they often look up at the murals above the cases. One depicts members of the Constitutional Convention. There stands Gerry, guardian over the documents he helped to bring to life. While Gerry is gone and forgotten, his work is not. All these visitors have to do is walk outside the Rotunda and look around Washington, D.C., to see evidence of his work and that of his contemporaries (both remembered and unremembered): the Capitol, the Supreme Court building, and the White House, representing the institutions he and his generation gave us.

Greg Bradsher, an archivist at the National Archives and Records Administration, specializes in World War II intelligence, looted assets, and war crimes. His previous contributions to Prologue have been "Taking America's Heritage to the People: The Freedom Train Story" (Winter 1985); "Nazi Gold: The Merkers Mine Treasure" (Spring 1999); "A Time to Act: The Beginning of the Fritz Kolbe Story, 1900–1943" (Spring 2002); and "The 'Z Plan' Story: Japan's 1944 Naval Battle Strategy Drifts into U.S. Hands" (Fall 2005). He named his first cat Elbridge in honor of Gerry.

Note on Sources

To large extent the story of the Constitutional Convention and Elbridge Gerry's role in its proceedings are found in the Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention (Record Group 360), Max Farrand's The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (4 vols., 1911), Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 Reported by James Madison (introduced by Adrienne Koch, 1966), and George Athan Billias's Elbridge Gerry: Founding Father and Republican Statesman (1976).