The Electoral College

A Message from the “Dean”

Fall 2008, Vol. 40, No. 3

By Michael White

In these final months of the 2008 presidential election cycle, I was asked to reflect on the role of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in the election process from my years as legal counsel for NARA's Office of the Federal Register.

When I began my career at the Federal Register in 1987, I had a vague notion of the Archivist playing a role in the election of the President. But I had no idea that my office would come to be known as the "home" of the Electoral College, or that in the remarkable election of 2000, the press would refer to me in jest as the "Dean of the Electoral College."

I learned soon enough that the 1985 legislation that created the independent National Archives also endowed the Archivist of the United States with responsibility for administering the Electoral College process on behalf of the states and the Congress. The Archivist delegates this function to the Federal Register, continuing a practice established by the administrator of General Services in 1951. Although NARA's election responsibility supports a critical function of government, it was rare for anyone outside the office to take notice of our work.

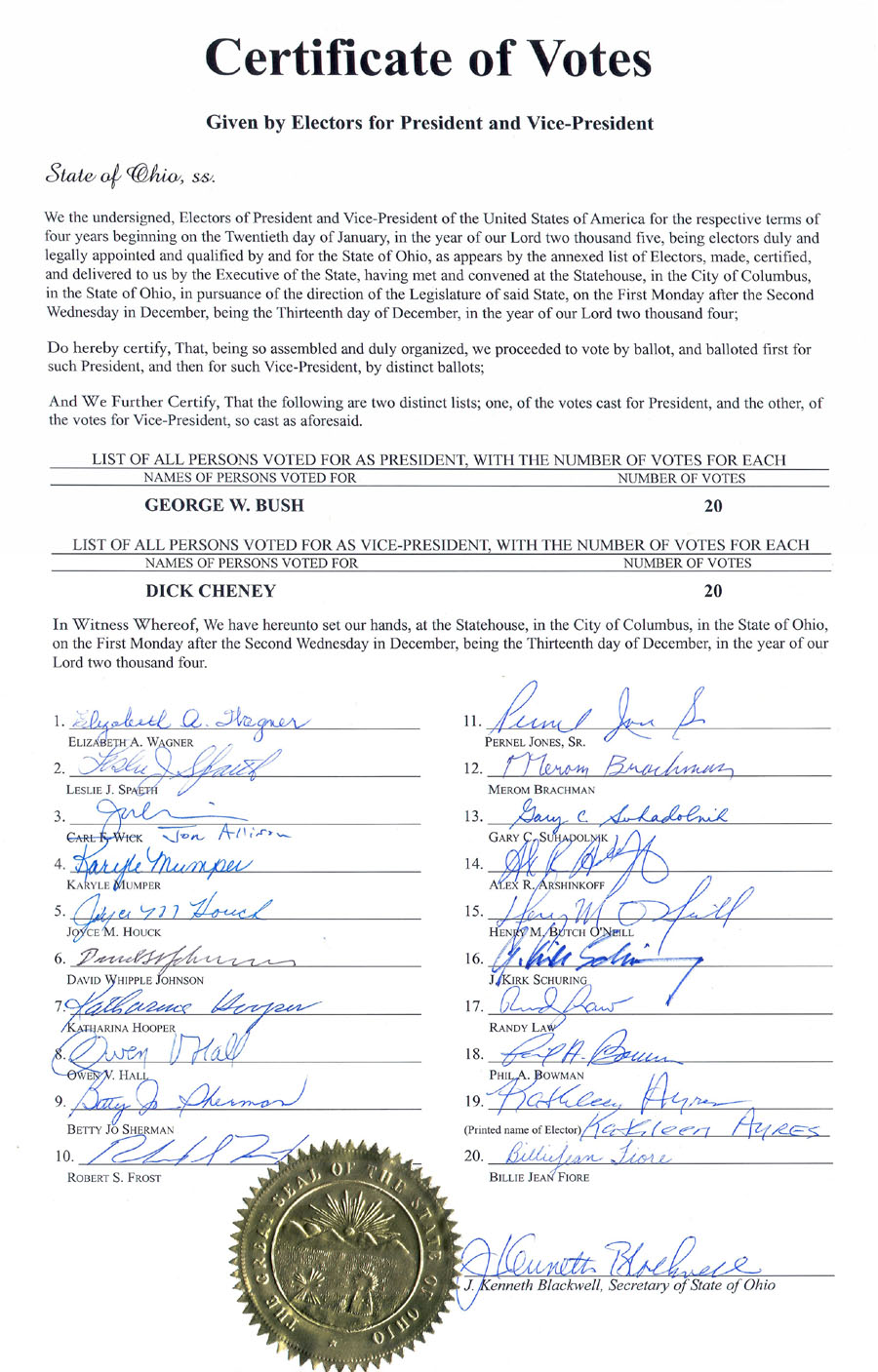

The presidential election process is governed by Article II, Section 1, of the U.S. Constitution and the 12th amendment, along with provisions of Title 3 of the United States Code. The current election code is still largely a product of reforms adopted after the disputed Hayes-Tilden election of 1876. Under the law, the governors of the states must authenticate their electors' credentials on "Certificates of Ascertainment" and submit them to the Archivist. Federal Register staff analyze the certificates for compliance with legal requirements and present copies to the secretary of the Senate and the clerk of the House of Representatives. This is followed by a second round, where each state transmits to the Archivist two "Certificates of Vote" that document their electors' votes for President and Vice President. One set of votes is earmarked for preservation in the Archives. The other is held in reserve subject to the call of the president of the Senate. The governors are directed to send a third set of votes directly to the president of Senate.

The president of the Senate is ultimately responsible for bringing forward the electoral votes for the official counting at a joint session of Congress in early January, two weeks before inauguration day. But as a practical matter, the Federal Register is uniquely positioned between the states and the Congress to oversee the entirety of the process and ensure that Congress has a full complement of votes to act upon.

A provision of law holds that the Senate's certificates are to remain under seal until the final count begins in Congress, presumably to eliminate the possibility of mischief or the appearance of improper manipulation. By contrast, Federal Register attorneys carefully vet the facial legal sufficiency of the two sets of certificates in their hands. If they discover correctable errors, they try to remedy them before Congress goes into session to finalize the election. Not all of this process is set out in statute, but the logic of the law leaves it to the Federal Register to inform the officers of the House and Senate of any irregularities and to coordinate state and federal actions for the final counting of votes.

The Founding Fathers designed the Electoral College as a temporary congress of citizen-electors with a narrow mandate. The electors convene for just one day, generally in their state capitals, pass a few parliamentary rules, cast their votes, and then retire from service. The institution of the Electoral College simply dissolves, only to be reconstituted four years later.

It is not unusual for state government election staff to completely turn over every few years as political fortunes change. When that happens, the incoming officials may not be well prepared to grapple with the stylized procedural language of the 19th century and some of the more arcane aspects of federalism. The citizen-elector idea is noble in concept, but from my experience, a completely transient process may not give the electorate great confidence in the outcome, nor does it offer state election officials a ready source of institutional knowledge.

The Office of the Federal Register began to address this issue in 1996. We decided to build a virtual home for the Electoral College on NARA's web site and began posting some informative internal documents that had never been widely distributed. We had only rudimentary skills for editing web pages, but a lot of determination.

By the end of the year, our new web pages displayed a procedural guide to the presidential election and the relevant legal provisions, the names of each state's electors, a complete set of "box scores" of past presidential election results, and a full explanation of the role of the National Archives. We also encouraged members of the public to ask questions by e-mail, which we could respond to online, creating a sort of web forum on the presidential election process.

Over the years, the Federal Register's legal staff, with great assistance from NARA's web program, has continued to improve the web site. We now scan images of all the electoral certificates and post them online within hours of verifying their legal sufficiency. The site is highly rated for its educational content, and on election day of 2004, we recorded just under 1 million "hits."

As we approached the election of 2000, our web site was primed to give state officials a ready reference source. But sometimes the greatest challenge in this process could be simply finding the particular state officials assigned to carry out the Electoral College function. As counsel for the Office of the Federal Register, it was my job to kick off our quadrennial duties by mailing election information to the governors of the 50 states and mayor of the District of Columbia.

We send instructions to the state and urge the governors to read them and to move quickly to assign capable staff to carry out the legal requirements.

Too often, Federal Register attorneys would later have to track down bewildered bureaucrats who were surprised to learn that they had been given this task. In a few instances, state officials assured us that we needn't worry about our quaint set of procedures because their state had "abolished" the Electoral College. After a quick explanation of the original Constitution, the 12th amendment, and a few lines of statute, we would hope for the best and promise to remain in touch.

There are more than a few things that can go wrong. Occasionally our attorneys notice that federal officials, such as members of Congress, have been chosen to serve as electors. Being employed by the federal government in a substantive capacity disqualifies a person from serving as an elector. With sufficient notice, a state can replace ineligible electors and submit corrected certificates. But if a state's Certificate of Vote fails to reach the Senate, those electoral votes would be nullified.

In years past, the Office of the Federal Register has retrieved missing electoral vote certificates from a variety of places, such as the White House, the General Services Administration, and the Department of State. It was not unusual for as many as half of the electoral votes intended for the Senate to be misdirected, which raised the stakes for the Federal Register to obtain the reserve set of votes for the Congress to act upon. On one occasion, the director of the Federal Register rummaged through mailbags for electoral votes at the post office on Christmas Eve. In another instance, I had to persuade a state trooper to interrupt his governor's winter holiday because the electoral votes were nowhere to be found. Sometimes an elector would forget to sign a Certificate of Vote. The only way to cure that defect is to find the elector and have the person amend the original document before the Congress meets to ratify the results. In the hunt for wayward electors, calling on the state police could save the day.

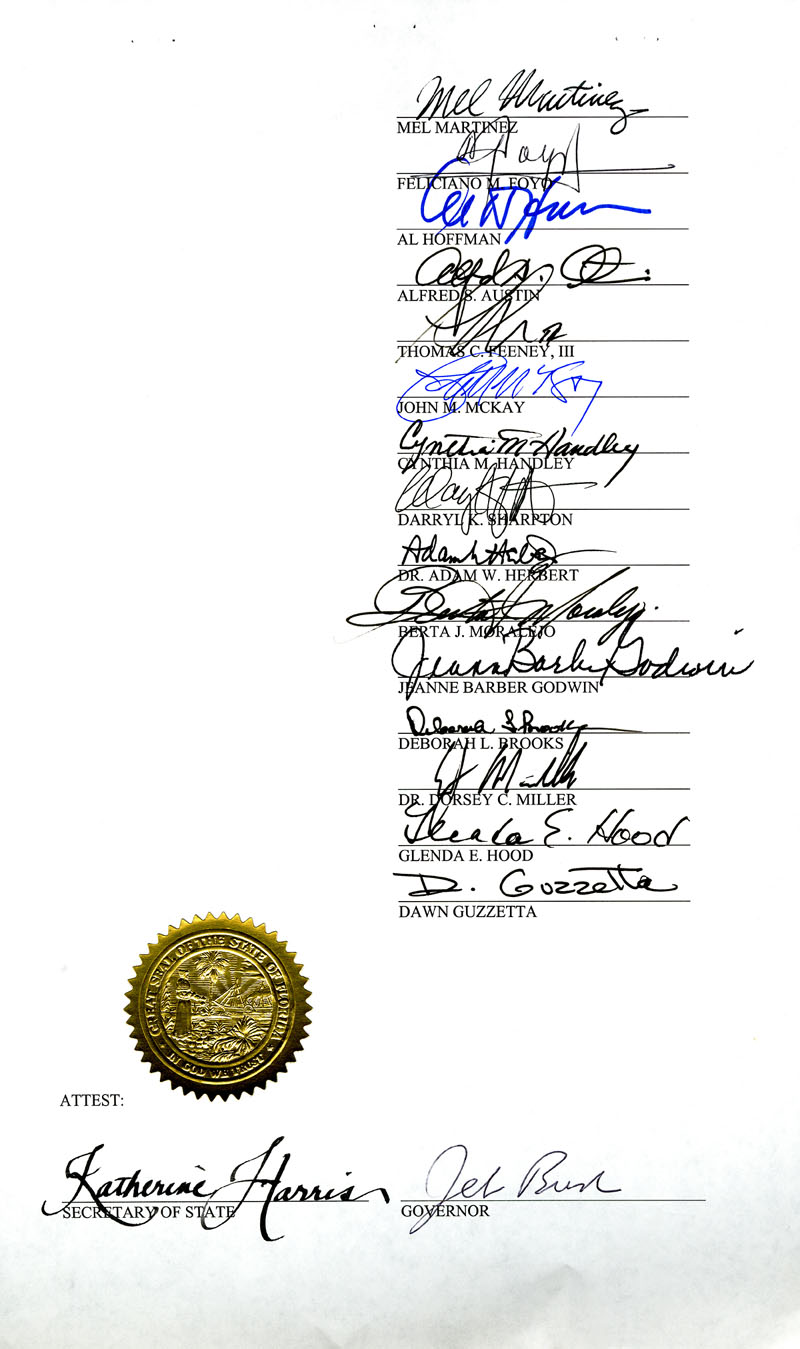

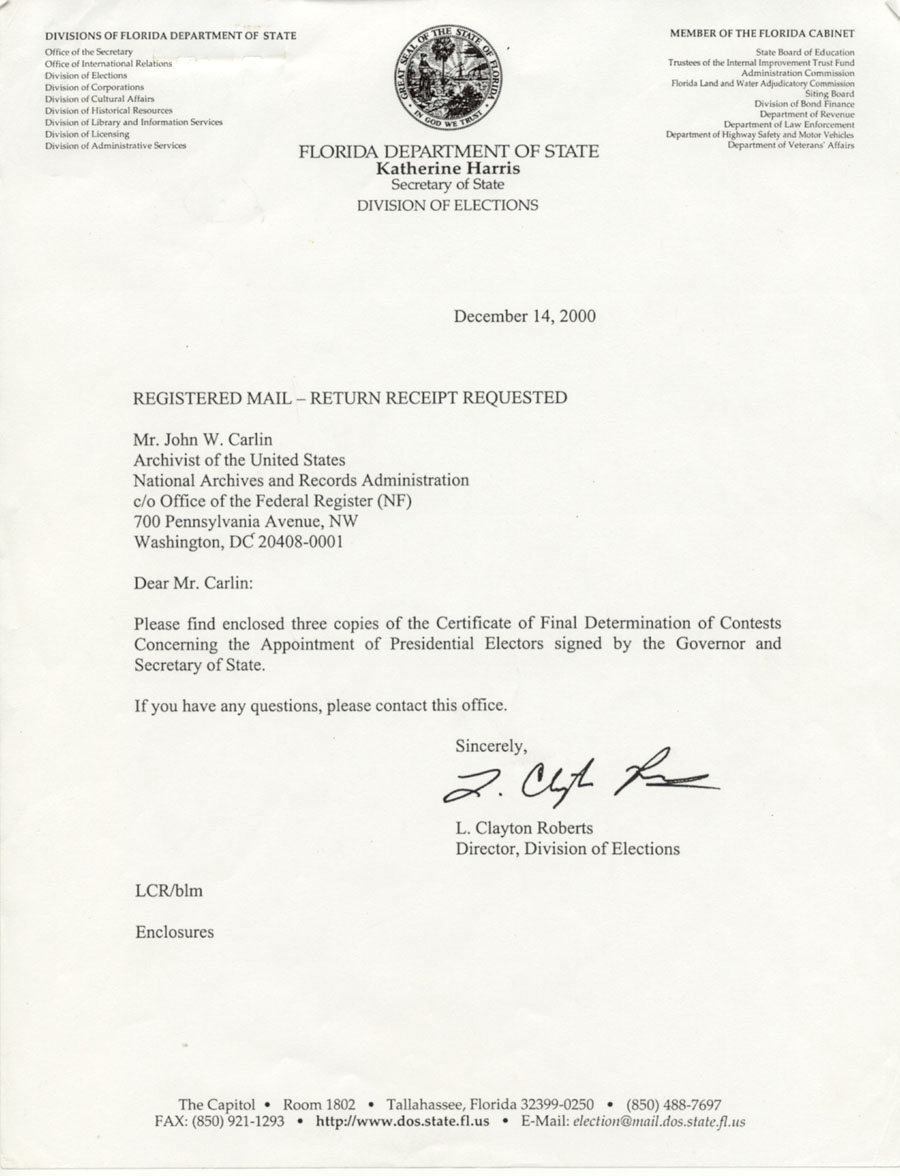

Public awareness of the Office of the Federal Register's stewardship of the Electoral College was magnified in the waning weeks of 2000 as the Florida recount controversy dragged on, before culminating in the case of Bush v. Gore. By December, the U.S. Supreme Court was poised to issue an opinion that would change the course of American history. The Court already had ordered Florida counties to stop the recount of votes, pending resolution of the case. With the presidency hanging in the balance, and the nation standing uneasily on the edge of a constitutional crisis, NARA occupied a portion of center stage. At the Federal Register, we carefully safeguarded the Florida Certificate of Ascertainment signed by Secretary of State Katherine Harris, which was the document at the very core of the dispute.

The news networks and major newspapers suddenly displayed a voracious appetite for explanations of the historical and legal intricacies of the Electoral College system. As the controversy grew, it would have been a natural reaction to withdraw from public scrutiny, to turn off the telephones, and ignore the e-mails. We were operating in a highly charged atmosphere, with election officials accused of acting improperly behind closed doors to skew the legitimate voting results. Instead, the Office of the Federal Register concluded that we must be as transparent as possible.

We believed it was essential for the American people to see that NARA would protect the integrity of the presidential election process and stand apart from all political influence. We were careful never to speculate, only to inform. Our Federal Register publications staff pitched in to answer all the e-mail questions; we accepted invitations to appear on nearly every major news network; we held informational sessions with the press; and we spoke to students at a university and a law school. Archivists at NARA also responded to requests for records of past elections as researchers looked to give new life to old electoral voting precedents.

While the nation waited for a definitive court decision, I received a call from officials of the Republican-controlled Florida legislature calmly stating that they were ready to break the electoral deadlock by divesting the matter from the federal and state courts. They asked me to specify a technical process to revoke the ascertainment of electors certified by the Florida secretary of state and replace it with a document that would list a new set of 25 Republican electors to be appointed directly by the Florida legislature. They were, in effect, going to declare a "no-decision" under an obscure provision of federal election law and use their direct appointment authority under Article II of the Constitution. The action was intended to preempt the U.S. Supreme Court arguments as to which slate of electors should be seated at the Florida meeting of electors. I explained that procedural precedent for such a "do-over" did not exist, but if the Florida legislature appointed its own electors, we would work out a way to follow the Constitution and federal law.

Initially I was surprised that the Florida officials were so open in consulting with me about their plan. Their approach would effectively discard the votes of Florida's citizens and toss a hot new document into our hands. I had an idea of how to proceed, but any misstep could embroil the Archivist in the litigation. In retrospect, it was reassuring that politicians with strong partisan interests placed their trust in us, taking it for granted that the Office of the Federal Register would act in good faith. We were being seen as we really wished to be seen—unbiased public servants sworn to uphold the rule of law, devoted to the preservation of American constitutional democracy.

Then on December 12, the Supreme Court announced its decision in favor of Governor Bush, making the contemplated action of the Florida legislature a moot point.

While other lawyers argued over the full meaning of the Court's decision in Bush v. Gore, the Office of the Federal Register pored over it for a procedural path to formally end the dispute over Florida's electors. Because federal law did not account for a "re-ascertainment" of electors after a partial recount of votes, we had to devise a new form of document to suit the Court's opinion. The Florida secretary of state submitted this unique final determination to us, and from our procedural point of view, the Florida electoral fight came to an end.

The Federal Register saw the election process through to the end, consulting with congressional officials over the details of the certificates, in preparation for the final tally of votes. Finally, on January 6, 2001, the director of the Federal Register and his legal staff sat in the gallery of the House of Representatives as Vice President Albert Gore graciously presided over a joint session of Congress that marked his own defeat. As he went through the certificates, the electors' votes were called out state by state, demonstrating who really elects the President and Vice President in a federal system of government. Gore had won the nationwide popular vote by a half-million votes, but in the final tally of the Electoral College, Bush edged him out by the slim margin of five electoral votes. A very old and little-known part of our government had played its role once again, with a historic impact, creating a new awareness of the many ways the National Archives serves our nation.

Michael White is the managing editor of the Federal Register. Until August 2007 he served as the Federal Register's chief counsel. He is active in the American Bar Association and was one of the principal architects of Regulations.gov, an award-winning e-Government service for commenting on proposed regulations. He received his B.A. from the University of Virginia and J.D. from the College of William and Mary.