Attacking the Backlog

NARA Archivists Mobilize to Make Unprocessed Records Available to the Public

Summer 2008, Vol. 40, No. 2

By Ashley Bucciferro

One million cubic feet. Two million boxes. Billions of pieces of paper. No, this isn't the cumulative total of records held by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). It's only the amount of records we received in our two Washington, D.C.–area facilities from 1995 to 2005. This was a decade of unprecedented growth. And while the amount of records has dramatically increased, the number of staff members has not. Normal operations didn't stop either.

NARA staff still had to provide reference services, bring in new records, and perform other processing activities during this 10-year period. NARA did not neglect this mounting backlog, but it could not invest the necessary resources to deal with it. In October 2006, this changed when the Office of Records Services–Washington, D.C., adopted a processing initiative.

Processing involves arranging, describing, and housing records in order to make them accessible. The processing initiative, which aims to erase the backlog in 10 years, has brought about sweeping changes to operations and practices and will ultimately allow enhanced reference services and more efficient access to the records at the National Archives.

"For a number of years, staff and managers in [Washington] were aware of the growing backlog of unprocessed records," said James Hastings, director of access programs. "When the new strategic plan for NARA was under consideration in 2005, this critical situation was recognized as an agency priority. This gave us the opportunity to prepare a 10-year plan that is consistent with the 10-year provisions of the strategic plan,"

Over three months, two teams examined reference and processing functions in Washington, D.C., and College Park, Maryland, to determine where changes could be made to improve efficiency. They carefully considered processing and reference needs and the resources necessary to meet them and established priorities and ways to track progress. Staff members also participated through open forums.

Before developing any strategies or goals, numbers had to be calculated. The backlog of 1 million cubic feet of records was already known, but exactly how much work needed to be done? An analysis of NARA's textual holdings found that 74 percent of textual records in Washington were not processed sufficiently to enable researchers to easily identify records of interest. Thirty-three percent of records did not even have the most basic elements of intellectual control, such as titles or dates.

A preservation survey showed that 57 percent of NARA's holdings needed holdings maintenance, such as new boxes and labels. A combined analysis of these results and others determined that NARA would need at least 4,000 employees to adequately process the records, meet holdings maintenance needs, and perform access review and restrictions. The actual number of available employees doesn't even come close to this number. NARA's total workforce nationwide is only about 3,000, and the Washington staff assigned to working with textual records in reference and processing is fewer than 140.

Even with these very limited resources, we knew that we could focus the energy and determination of the existing staff to tackle the backlog. As Archivist of the United States Allen Weinstein said, "despite the fiscal restraints, we are determined to provide more effective services to the public by refocusing our attention and resources on reducing, and in time eliminating, the backlog."

In 2006 the staff and managers responsible for textual records spent several months analyzing how they used their time over the years. Previously, employees had to split their time between processing and reference work, but "the reference load made it essentially impossible to perform any processing to speak of, and eliminated any large-scale projects," explained senior archivist Patrick Osborn. The analysis determined that employees could get far more processing done if they did not also have reference assignments. The number of staff members needed to continue excellent reference service was calculated to be 39.

Now, these 39 staff members are assigned to reference, and the remaining staff are processing the backlog. This assignment of people ensures that we have sufficient resources to continue reference service and to focus new attention on processing.

Establishing the number of reference staff at 39 required some streamlining. "We were able to demonstrate that we could maintain a high level of reference service even with the significant increase in the number of full-time employees assigned to processing," said Hastings. A major feature of streamlined reference was the formation of teams. By making teaming and collaborative planning the hallmarks of our initiative, we have ensured that there is the right mix of knowledge and skills to get the job done, to broaden the knowledge and skills of less experienced staff, and to soften the blow of the "brain drain" when experienced staff members retire. The use of teams and collaborative efforts not only works for reference services, but it also works for processing.

One team is the Accessioning Team, which transfers new records to NARA from records centers like the Suitland, Maryland, facility. The team also performs initial processing functions such as record verification and determining proper location. An National Archives Catalog team has also been created. ARC, which is NARA's online finding aid system, contains descriptions of series, file units, and items; it is found on the National Archives web site at www.archives.gov/research/search/. The ARC team creates ARC entries for newly processed series and puts them intothe National Archives Catalog, making them available to the public. The ARC team often completes the final step of processing by creating the finding aid and appropriate research tools. Military and civilian teams work on priority record groups and series.

By concentrating efforts into teams, more work can be accomplished more effectively. "Teams are important because they compile multiple talents. You can count on everyone's skills to complete the final project," said supervisory archivist Patricia Anderson. The adoption of teams, the distinctive split between reference and processing, and flexible staff, make the goals of the processing initiative attainable.

What is involved in order to adequately process records?

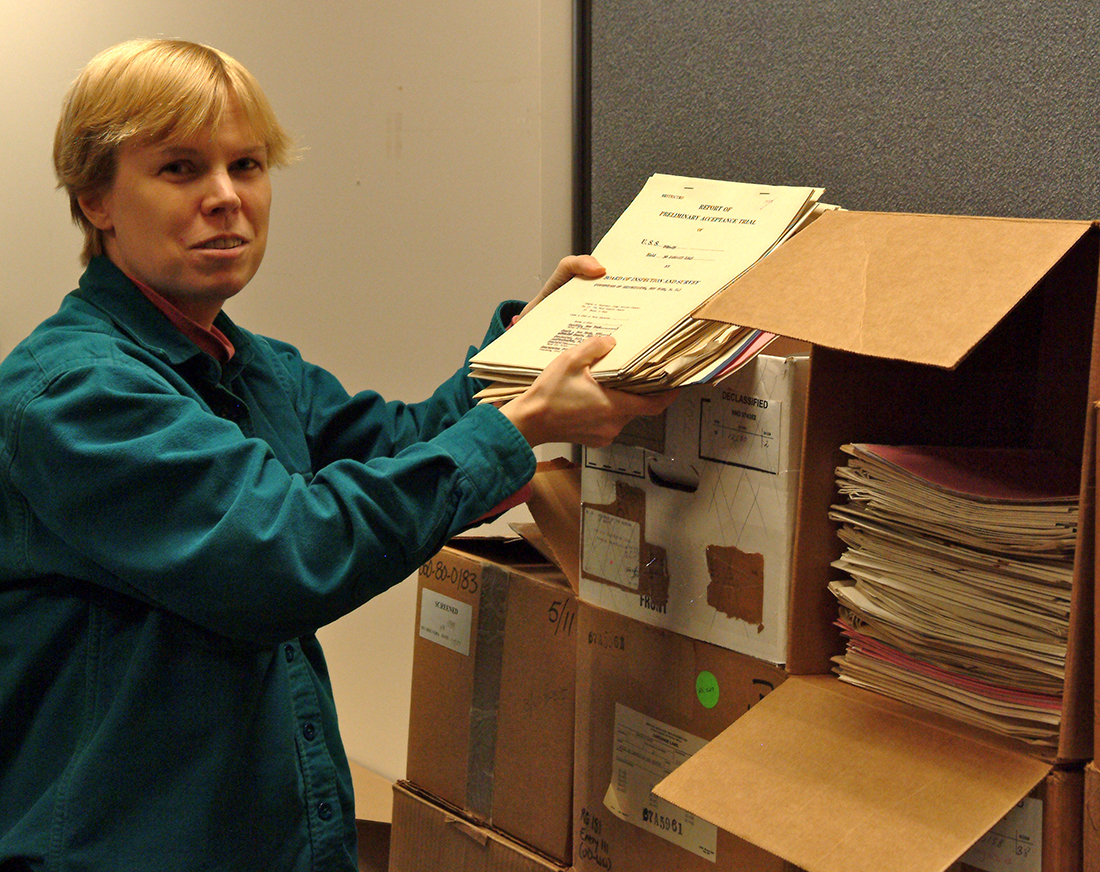

Once all unprocessed records are identified, our experienced archivists rank record groups by the amount of reference use they generate, with those receiving the highest use getting processed first. The first step is then basic processing—preparing, housing, and describing the records to the level necessary for sufficient access. This can include reboxing records from large boxes to smaller archival boxes, combining records into one series, and completing a basic description. The basic description includes an informative title with dates, an arrangement statement, holdings measurement information, and a scope and content note. We then enter this description into ARC. Basic processing is usually adequate for most access and research purposes. These steps can be completed by one individual, or more likely by teams. Again, teamwork plays a critical role in the processing effort. When a series description goes into ARC, the whole world will then be able to know what the records are and where they are located. Before this, the unprocessed series was largely unknown.

Some records—especially those that have high reference use, require more extensive attention. This could include flattening trifolded documents, removing moldy or broken bindings, or putting photographs into polyester sleeves. Detailed descriptions may also be created, such as folder lists or even item-level lists.

What has been accomplished since the start of the processing initiative in fiscal year 2007? As of October 2007, more than 25,000 series have been processed, totaling more than 168,000 cubic feet. This is more than 10 percent of the backlog, an impressive start for the inaugural year. As Ann Cummings, chief of the Processing Unit in College Park related, "the entire team, from management to line staff, can be proud of what we have been able to accomplish in such a short time. I believe we can maintain the momentum which we have started."

In Washington, staff from various units described more than 6,000 series from Records of the U.S. Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393. These records are a rich source for the history of the American West and attract a great deal of researcher interest. The staff also completed microfilming service records of the U.S. Colored Troops and records from the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War.

In College Park, both civilian and military staff processed an impressive amount of records. Previously unarranged FBI case files are now arranged numerically under the appropriate regional field office. The Office of Strategic Services personnel file, with an alphabetical arrangement of more than 20,000 files, now takes less than 10 minutes to search instead of an hour. Nearly a quarter million documents encompassing 2,000 cubic feet of Navy technical reports are almost fully processed. Department of State records of consular posts and embassies were once extremely cumbersome to use but are now fully accessible with the creation of thousands of box lists and ARC descriptions documenting their contents. Other records processed in 2007 came from the Department of Justice and several modern military departments.

Processing these types of records at this capacity is not easy. Staff members have to work with records they may be unfamiliar with, and because we aim to eliminate the backlog, expectations are much higher than before. Staff have risen to the challenge. The results have been well worth it, and access has already improved.

"Processing has taken a pivotal role in providing access to important historical records," said Cummings. "We anticipate that as more and more of the collections are appropriately arranged and described, the processing initiative will prove to be of continuing value."

What does all this mean for researchers?

Researchers will enjoy, and have already begun to see, the benefits of the initiative through better description, improved holdings management and preservation, and increased online resources. Better description leads to a more accurate and concise search for desired records and information. In the past, some records may have only been minimally processed and given a name like "Miscellaneous Records," with no indication of what is in that series.

Now, that same series may be titled "Records Relating to the Dedication of the Lincoln Memorial," with a clear description attached. Improved holdings make records more accessible to researchers. They are easier to locate and retrieve and are better organized, cleaner, and easier to navigate. Also, proper preservation ensures the records will last for future researchers.

Finally, increased online finding aids and resources allow for more virtual research. "ARC allows for records description to be streamlined, and the finished product can reach researchers a lot more quickly," explained archivist Joseph Schwarz. An interested user does not need to visit or directly contact the National Archives but can search ARC to see what is available. ARC and other online resources also promote the use of the Archives and make it clearer to users what NARA does and what it has.

The processing initiative has been a difficult transition for staff. Now, however, employees are no longer torn between providing reference service to customers and working on processing projects because their focus has become more clearly defined as one or the other. There are now uninterrupted periods of processing, and both reference and processing receive some priority.

According to Rick Peuser, the assistant chief of reference at College Park, "the processing initiative is bringing much better information about our records to staff and researchers. Processing is improving the reference services we deliver."

Ashley Bucciferro is an archivist in the processing unit at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. She has a master's degree in library science from the University of Maryland, College Park. Her past projects at the National Archives include processing consular and embassy records and National Park Service records.