Slavery and Emancipation in the Nation's Capital

Using Federal Records to Explore the Lives of African American Ancestors

Spring 2010, Vol. 42, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By Damani Davis

On October 6, 1862, in the nation's capital, two families appeared before a federally appointed board of commissioners that administered all business relating to the April 16 Emancipation Act that abolished slavery in the District of Columbia.1 Alice Addison, the head of a formerly enslaved African American family, was accompanied by her two adult daughters, Rachel and Mary Ann, along with Mary Ann's three children, George, Alice, and James. The other family, their former white owners, was headed by Teresa Soffell, a widow. Her three sons, Richard, John, and James, and her two daughters, Mary and Ann Young, accompanied her. A mutual desire to officially register the Addison family's new status as freed persons prompted their joint appearance. The Soffells hoped to gain the financial compensation promised by Congress to all former slaveholders in the District who had remained loyal to the Union; the Addisons simply desired the comfort and security of having an official record certifying their freedom.

The Soffells had missed the July 15, 1862, compensation deadline mandated under the terms of the April 16 act.2 The Soffells explained to the commissioners that they failed to petition by the deadline because the Addisons were no longer residing on their property at the time the act went into effect.3 The Addisons had fled the city three days earlier on April 13, fearing that President Abraham Lincoln and the federal government planned to forcibly deport them—along with all other ex-slaves—to Africa. The report noted that the Addisons had fled to their father's residence (the father of the two adult daughters) who lived in Montgomery County, Maryland, and was a slave owned by a Harry Cook. The Addisons remained there until September 28, 1862, when they returned to Washington, D.C.4

This glimpse into the lives of two Washington area families—former slaves and slaveholders—is preserved in federal records that relate to slavery and emancipation in the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia before and during the Civil War era. These records contain personal information such as names, ages, physical descriptions, and places of residence, as well as collateral information casually provided in recorded testimonies. As shown in the Addison family's case, information concerning the daughter's enslaved father—including details concerning his residence in Montgomery County and the full name of his owner—is found in their testimony explaining their flight.

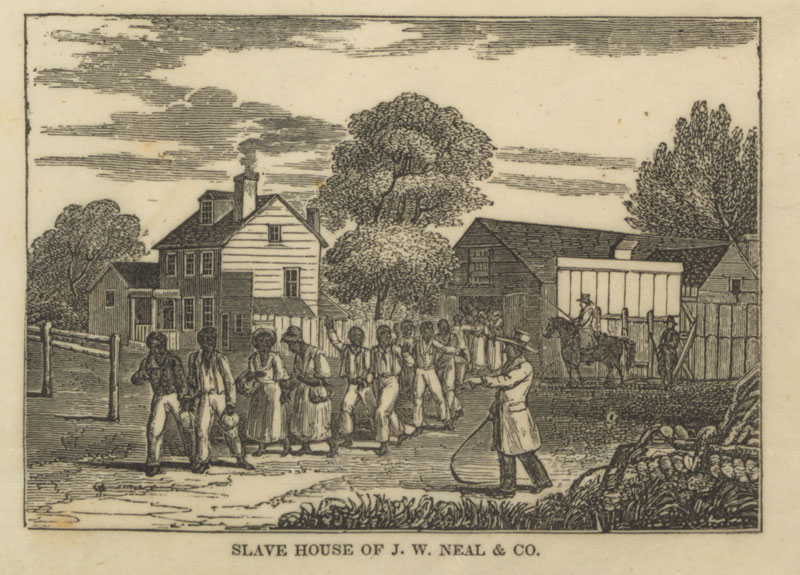

Slavery existed in the nation's capital from the very beginning of the city's history in 1790, when Congress created the federal territory from lands formerly held by the slave states of Virginia and Maryland. Because of its advantageous location between these two states, Washington became a center of the domestic slave trade in the 19th century and was home of one of the most active slave depots in the nation. The rapid expansion of cotton as the primary cash crop for states throughout the Deep South generated a renewed demand for slave labor. Planters and slave dealers in the declining tobacco-centered Chesapeake region of Maryland and Virginia, sought to capitalize on this demand by selling their surplus labor in a burgeoning domestic slave market. As one historian notes, "Washington offered dealers a convenient transportation nexus between the Upper and Lower South, as the city connected to southern markets via waterways, overland roads, and later rail."5

Within the District of Columbia, slave dealers housed the slaves in crowded pens and prisons as they waited to sell them. "Slave-coffles," long lines of shackled blacks marching from one site to another, gradually generated controversy throughout the nation. As Washington became the focus of abolitionism in the decades before the Civil War, antislavery activists argued that such scenes in the nation's capital disgraced the nation as a whole and its ideals. The Compromise of 1850 abolished active slave trading within the boundaries of the District, but the trade continued to flourish in Maryland and Virginia. As tensions increased nationally in the years leading up to the Civil War, slavery in the nation's capital continued to be a subject of special focus, activism, and compromise.6The numbers of slaves gradually declined in the District throughout the early 19th century—from approximately 6,400 slaves in 1820 to 3,100 by 1860. Throughout the 1800s, many owners voluntarily manumitted their slaves. Of the city's black population in 1800, those who were enslaved outnumbered those who were free by four to one; however, by 1860 the number of free blacks actually exceeded the number of slaves by three to one.

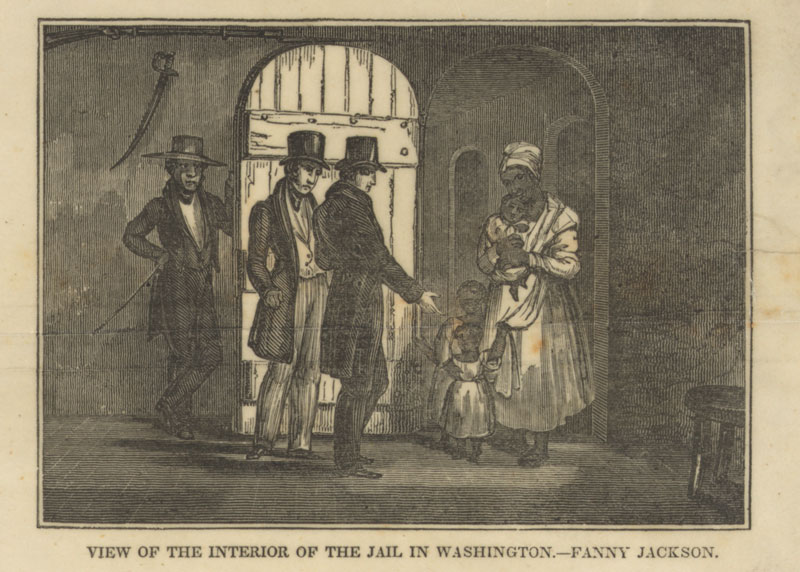

In the years leading up to D.C. emancipation, the typical slave in Washington worked in some form of domestic service, and female slaves outnumbered males. On the surface, the nature of the institution seemed relatively benign compared to the harsher forms of plantation slavery in parts of the rural South, and most blacks in the District were free. Despite appearances, all African Americans in Washington—both enslaved and free—lived in a state of constant vulnerability. Those who were enslaved feared being sold further south and separated from family and loved ones. Free blacks were required to always have on their person a copy of their "certificate of freedom," and the burden of proving their status was on them. Without proof of status, free blacks could be jailed at anytime. Even if they subsequently proved their status, detained blacks still were responsible for paying for the cost of their stay. If they failed to prove their free status in sufficient time, they risked being sold further south into slavery.

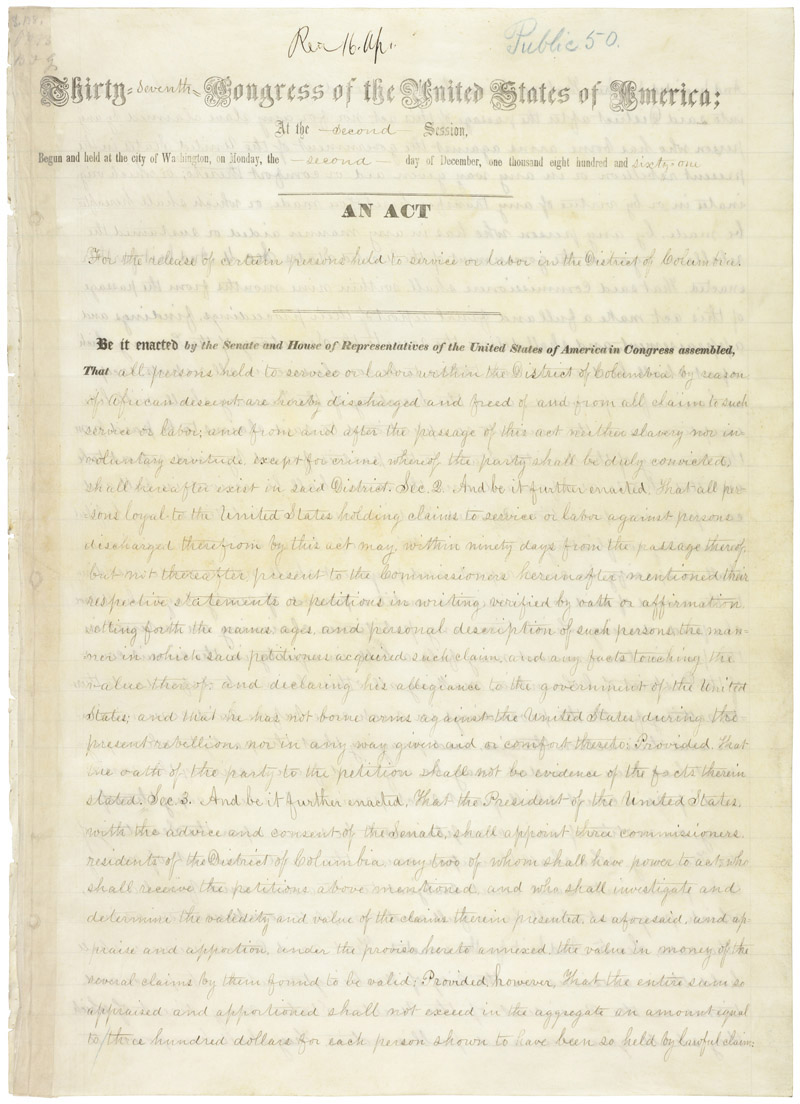

Slavery remained legal in the District until April 16, 1862, when President Abraham Lincoln signed into law an act abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia (12 Stat. 376). The D.C. Emancipation Act originally provided for immediate emancipation, compensation to loyal Unionist masters of up to $300 for each slave, and voluntary colonization of former slaves outside the United States. The act required owners claiming compensation to file schedules listing and describing each slave by July 15, 1862. A supplementary act of July 12, 1862 (12 Stat. 538) permitted the submission of schedules by slaves whose owners lived outside of the District of Columbia if the slave had been employed with the owner's consent in the District any time after April 16, 1862. The emancipation records consist of the schedules and supporting documentation submitted as a result of these two acts.

The records are organized generally by the last name of slave owner (act of April 16, 1862) or by the last name of slave (act of July 12, 1862). Several series of records relating to slavery and emancipation in the District of Columbia have been published on microfilm and reproduced on research web sites such as Ancestry.com and Footnote.com. Records of the Board of Commissioners for the Emancipation of Slaves in the District of Columbia, 1862–1863 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M520) relates directly to the management and dispensation of the emancipation acts of April 16 and July 12, 1862. Records of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Relating to Slaves, 1851–1863 (M433), and Habeas Corpus Case Records, 1820–1863, of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia (M434), contain records relevant to the broader history and social presence of slavery in the District of Columbia.7

The Board of Commissioners for the Emancipation of Slaves, 1862–1863

These records relate to the board of commissioners that administered the D.C. emancipation and document compensation petitions by slaveholders, pursuant to the acts of April 16 and July 12, 1862. For the first act of April 16, a total of 966 petitioners submitted schedules claiming and describing 3,100 slaves. Under the supplementary act of July 12, another 161 individuals submitted claims, including formerly enslaved African Americans who were authorized to do so if their owners had failed to claim by the deadline of the first act. The board's records are found among the Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury (Record Group 217).

The petitions include the names of the slaveholders, the names of the slaves, physical descriptions of each slave, and the monetary value for the each claimed slave. The slaveholders often gave very detailed descriptions of their slaves, apparently hoping to reap a greater compensation for highly prized slaves. Eliza W. Ringgold estimated that her slave, Perry Goodwin—who was a gift from her deceased sister—was worth $1,500 and described him as a "portly, fine looking dark mulatto, about 5 ft. 9 inches" who was "healthy, of good address, a very intelligent young man, an upholster by trade . . . a good rough carpenter, and very handy at any kind or work" with no infirmities or defects either "morally, mentally, or bodily."

In the petition submitted by slaveholder Clark Mills, Philip Reid—distinguished as the slave who crafted the "Statue of Freedom" for the U.S. Capitol—is also valued at $1,500 and is described as a 42-year-old man of "mulatto color, short in stature, in good health, not prepossessing in appearance, but smart in mind, a good work man in a foundry, and has been employed in that capacity by the Government, at one dollar and twenty five cents per-day."8

Emancipation Papers, Manumission Papers, Affidavits of Freedom, and Case Papers Relating to Fugitive Slave, 1851–1863

The records of the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Columbia (in Record Group 21) contain the bulk of documents relating to both free blacks and enslaved blacks who resided in Washington, D.C., and surrounding counties during the antebellum and Civil War eras. The circuit court records include:

- Manumission papers for blacks who were voluntarily freed by their owners during the decade before the 1862 act

- Emancipation papers for those freed as a result of the 1862 act

- Affidavits or certificates of freedom (the official records of proof certifying the status of free blacks)

These files reveal information about free and enslaved individuals from a variety of backgrounds who were part of the everyday life and culture of the region.

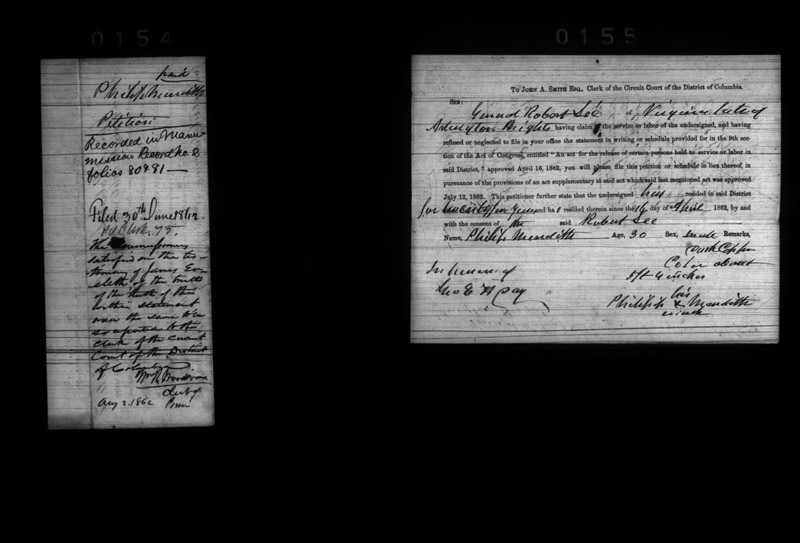

Philip Meredith's emancipation petition documents that the 30-year-old African American claimed to be the former slave of "General Robert Lee of Virginia, late of Arlington Heights." Meredith stated that General Lee had hired him out from his estate in Virginia to work for a third party in Washington City. Meredith apparently submitted his own schedule according to the terms of the supplementary act of July 12. Since his owner, Robert E. Lee, had not petitioned for compensation and Meredith was hired out, working and residing in the District of Columbia at the time of emancipation, the supplementary act qualified him to file for freedom.9

The records of Thomas Sumerville, a free African American from St. Mary's County, Maryland, show that Sumerville successfully purchased and freed his enslaved family, which included his wife and three small children. His proof of ownership, which documented the purchase of his family from the original owner, Mary Watts, states:

Know all men . . . that I Mary Watts of St. Mary's County and State of Maryland for . . . the sum of seven hundred dollars current money . . . paid by Thomas Somerville F.B. [free black] . . . do grant bargain and sell unto [him] . . . Maria aged twenty six years, one Negro child named Sarah Ann aged six, one negro child named Thomas Randolph aged three years, and one other negro child named Mary Ellen aged one year . . . 26 December, 1849.

The file includes Thomas Sumerville's deed of manumission for his wife, who was officially freed by him several years later, stating:

To all whom it may concern, Be it known that I, Thomas Sumerville . . . do hereby release from slavery, liberate, manumit, and set free my wife Maria being of age thirty four years and able to work and gain a sufficient livelihood. . . . I do declare [her] . . . discharged from all manner of service or servitude to me my executors or administrators forever.

The case of the Sumerville family shows how free and enslaved blacks were often linked by familial bonds. It also shows how free blacks would sometimes purchase enslaved loved ones to grant their freedom.10

Alfred Pope, a notable figure in Washington's African American history, was originally owned by South Carolina congressman Col. John Carter. Pope first appeared in public records as a participant in "The Pearl Affair." In April 1848, 77 slaves—including 38 men and boys, 26 women and girls, and 13 small children or infants—embarked on a schooner, the Pearl, and sailed up the Potomac with hopes of making it to the North. A militia on a steamboat overtook the Pearl at the mouth of the Chesapeake. The majority of the slaves' owners sold the captured fugitives to states in the Deep South; a few, Pope among them, escaped that fate. Later as a free man, Pope became a highly successful businessman, a landowner, a community leader in Georgetown, and a leading member of the black community in Washington.11

Pope's file contains a letter written by a white witness, John Marbury, the executor of his deceased owner's will. Pope submitted the letter to the circuit court to confirm that he was indeed free and to explain how he had lost earlier documents proving his freedom.

The bearer, Alfred Pope, a coloured man, who will hand you this note was a servant of the late Colonel Jno Carter of this town. . . . By Colonel Carters will Alfred was set free, & is now, with my consent as Executor, in the enjoyments of his freedom. . . . Alfred caused this necessary certificate of his freedom to be entered on record in your office & had in his possession a certified copy. About a week since . . . his dwelling house . . . took fire in the night & was destroyed with all his furniture. . . . Alfred wishes to leave the District in search of employment and wants to obtain a copy from the record of the evidence of his being a freed man. I would accompany him to your office to offer in person my testimony to the aforegoing facts but I am very unwell & unable to do so—will you be so kind as to render him the service he needs, by giving him the renewed evidence of his freedom in the proper form? very respectfully, Jno Marbury.12

As part of the Compromise of 1850, the act of September 18, 1850 (9 Stat. 462) provided that claimants to fugitive slaves could recover their slaves, either by applying to federal judges and commissioners for warrants to arrest the fugitives or by arresting the slaves and taking them before the judges or commissioners to establish ownership. The fugitive slave case records are organized by date and contain warrants for arrest and documentation of proof of ownership.

The file of Mary Ann Williams, a fugitive and accused runaway, contains the warrant for her arrest.

Whereas Mary Massey of . . . Alexandria, State of Virginia hath applied to the Circuit Court for the rendition to her of a certain black negro woman named Mary Ann Williams . . . You are hereby commanded forth with . . . to arrest her . . . she being found in your bailiwick, and her safety keep, so that you have her body before the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, . . . immediately.

Upon the capture of Mary Ann Williams, she was delivered back to her owner, Mary Massey:

the said Mary Ann Williams being brought into Court by the Marshal on a warrant issued by the Court in these premises, her identity having been proved by Rudolph Massey—it is thus . . . ordered . . . that the Marshal . . . deliver her[e] the said Mary Ann Williams to the said Mary Massey; and . . . Mary Massey is authorized . . . to transport the said Mary Ann Williams to the State of Virginia from where she escaped.

For those fugitives who successfully eluded capture, there would be no record other than the initial warrant for arrest.13

Habeas Corpus Case Records, 1820–1863

A "writ of habeas corpus" is a court order instructing those accused of detaining another individual unjustly to bring the detainee before the court, usually to explain the reason for the detention. Many of the habeas corpus records issued by the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Columbia concern African American detainees accused of being runaway slaves. The records in each file may include petitions for habeas corpus, writs of habeas corpus, manumission papers, statements of freedom, and other papers needed for the proceedings of each case.

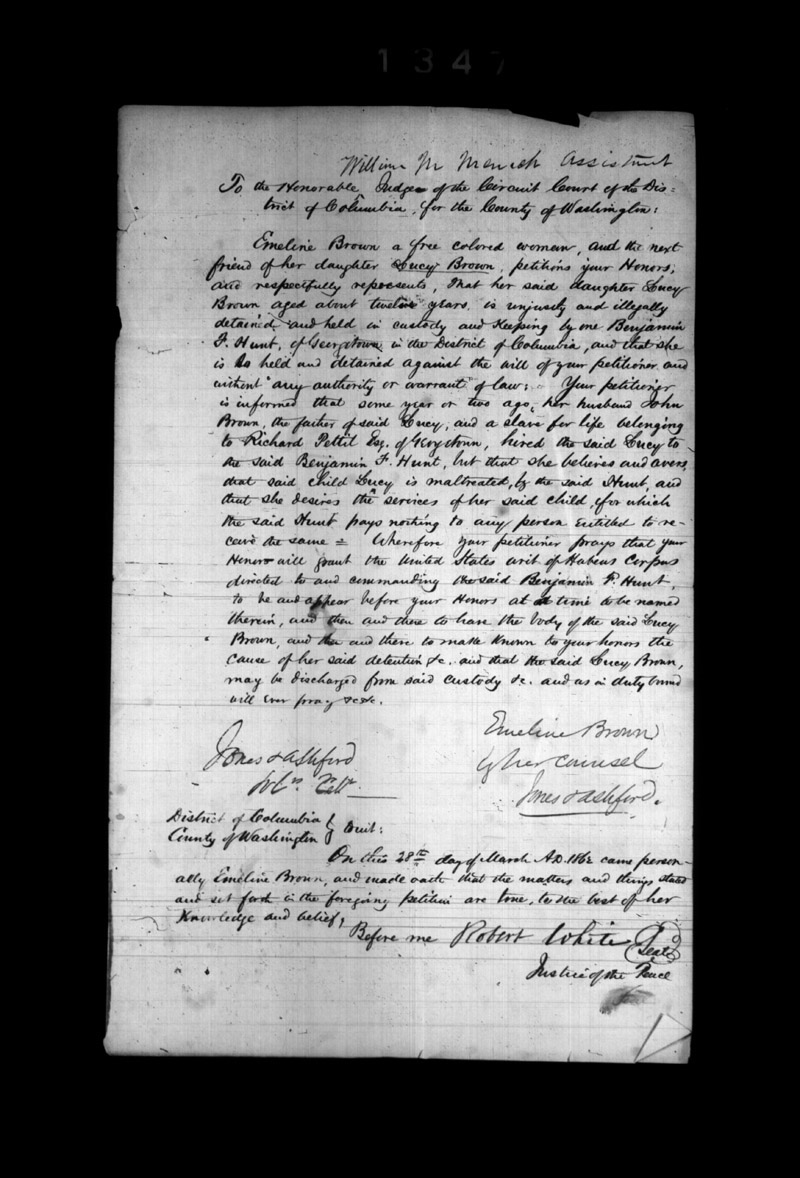

On March 22, 1862, Emeline Brown, described as a "free colored woman," submitted a habeas corpus petition. Her case highlights the reality that even free blacks faced the danger of being subjected to involuntary servitude. Brown petitioned for the recovery of her daughter Lucy Brown, who was "unjustly and illegally detained and held" against her will in the custody of Benjamin F. Hunt of Georgetown. Emeline explained that, about a year or two earlier, "her husband John Brown, the father of said Lucy, and a slave for life belonging to Richard Pettit Esq. of Georgetown," had hired out Lucy to Benjamin Hunt. Emeline contended, however, that Hunt had severely maltreated Lucy and that she now desired the return of her child. Several months later, the records show that Lucy's father, John Brown—now emancipated and described as a "free man of color of Georgetown"—submitted a second habeas corpus petition charging that "his child Lucy Brown . . . about 11 years, is unlawfully detained and restrained of her liberty" by the same Benjamin Hunt; and that Lucy had "not been bound out or indentured" to Hunt "who is in no wise entitled to detain her." John Brown asserted that he was the "natural guardian and protector" of the said child. On November 10, 1862, the circuit court ordered that "Lucy Brown be remanded to the custody and control of her father, the said John Brown, and the said Benjamin F. Hunt no longer detain or restrain her."14

Elizabeth Contee, "a free colored woman residing in Washington, D.C.," petitioned for habeas corpus for her detained brother, "a colored boy aged about 7 years named Basil Barnes." Elizabeth insisted that she was Basil's nearest legal relative and stated that he had been "fed and nourished by her, and all his wants provided for" until July 28, 1850, "when one William A. Mulloy came to her residence and forcibly took" him from her premises to some place unknown. Elizabeth further claimed that Basil was free and born of a free woman—their mother, Rachel Barnes—who was "now dead long previous to the act complained of." Elizabeth provided to the court proof of her status—her free papers and those of her deceased mother. Elizabeth also gave information on Basil's father, "John Olliday" [sic], who was a slave owned by a "Mrs. Lyell or Lyells, residing in the neighborhood of Georgetown." A white witness named Oswald B. Clarke testified in support of Elizabeth, claiming that he "saw Mulloy take the child." Detailing the incident, Clarke revealed in his recorded testimony that he saw William A. Mulloy, on the afternoon of friday the 26th of July last, take from the yard, of Elizabeth Contee a free colored woman . . . a colored boy aged about seven or eight years. Said Mulloy was on horseback accompanied by a man on foot. Said Mulloy placed the boy on the horse behind him. The boy was evidently taken off forcibly. And said deponent further declares that the boy was taken in spite of the entreaties and protestations of said Elizabeth Contee.15

On August 8, 1850, the court ordered Mulloy to appear with Basil before the court for a hearing, but there is no record of the final outcome.

African Americans submitted petitions for habeas corpus not only against white detainers but also against other African Americans. Robert Nelson, a free black "minor of about 17 years" was in a legal apprenticeship arrangement with another free black named Alfred Jones. Robert sued Jones for an annulment of the contract with the help and support of his friend Edward Woodlond, another free black. The official petition states:

Robert Nelson (a free boy of color) . . . is now held and confined in the possession of one Alfred Jones (a free man of color). . . . Alfred Jones claims the right . . . by virtue of a certain deed of indenture executed by his [Nelson's] mother (Patsey Nelson, since deceased). . . . [Of said indenture] your petitioner alleges is defective . . . having been executed while the orphan's court . . . was in session . . . and [yet had] never been . . . filed among the records of the orphan's court. [And claims further that] Alfred Jones has treated [him] with harshness and cruelty, often beating him, cuffing him in the most cruel and improper manner—that he has failed to supply him with proper food and clothing—that he has failed to send him to school and church—and to teach him any trade—and that he has failed in all respects to give him proper training or make proper provisions for him.16

The records in this file show that the court required Alfred Jones to release Robert Nelson so that he could plead his case. Again, there is no record of the final outcome.

Granville Williams, a recently freed African American from Christiansburg, Virginia, was arrested as a "runaway slave" while passing through Washington, D.C. Granville petitioned for habeas corpus after being detained for several months in a D.C. jail. When notified of Granville's incarceration, R. D. Montague, a white witness and associate from his hometown, testified on Granville's behalf, confirming that he was indeed a free man. Montague's testimony coincidentally reveals biographical information on Granville and an interesting family history.

Dear Sir, I have just received your note . . . and hasten to inform you that the boy Granville Williams is free. he is the son of Solomon Williams who formerly resided here but left several years ago with a view of going to Liberia. as it was understood, this boy . . . was at that time an indentured apprentice to Mr. Floyd Smith; and several of us endeavored to procure his release by Mr. Smith, who refused to let him off, in fear that he might accompany his father and family to Liberia. Mr. Smith was a Tanner, & having sold out, transferred the remainder of his time to Mr. George Keister of Blacksburg. His whole story is correct, and if I thought that there would be any doubt about his release, I would furnish any amount of testimony in favour of his freedom.

The judge ordered Granville released on July 25, 1855, stating that, "Upon an examination of this case . . . I am satisfied that Granville Williams is a free man and do order him to be discharged from custody."17

A similar case is that of Paten Harris, a free black who was arrested twice and jailed as a runaway slave while traveling by train from Virginia to Ohio. He was first arrested while passing through Richmond and again while passing through Washington, D.C. In Washington, Harris spent nearly a year in jail. His petition for habeas corpus states, "Paten Harris respectfully represents to your honors that he has been for the last eleven months and is now illegally held in confinement in the jail of Washington County as a runaway slave." Edward H. Moselly, the executor of Harris's former owner, eventually sent a detailed letter to the court verifying that Paten was indeed free, and in doing so, he revealed much information concerning his family history.

I was the [executor] of Ann H.W. Harris who died in 1832 . . . and by will directed that after all her just debts were paid, her slaves should be liberated. I succeeded by keeping together and hiring them out for several years in paying off all her debts and four or five years ago in setting them all free—this boy Paten went off with the rest and until last spring I supposed he was in Ohio but some time in April . . . I received a note from him informing me he was confined in jail in Richmond. I immediately went down and had him set at liberty, carried him to the Railroad depot, and put him in the care of one of [the] clerks to be sent on to Washington the next morning. I paid his passage and gave him some money to pay his expenses on the way. I also gave him a deed of Manumission. I believe I had the certificate of General Lambert the Mayor of Richmond attached to it—Edwin Clarke a clerk on the Richmond & Petersburg Rail Road gave him certificates [to travel through] Washington without interruption: Now if he has preserved these the proof will be irresistible that he is the same boy and will I think be set at liberty at once—but to test his identity ask him the names of his fellow servants set free by his mistress—There was Tom[,] Stephen[,] Davy[,] Ned (I believe Paten's brother), Antony, Betty (I believe the mother of Paten[,] Ned & Matilda) and Ginny. I do not recollect any marks that Paten has. he is about 25 or 6 years old, complexion black and about five feet 8 or 9 inches high.18

Paten Harris was set free in May 1843 after being arrested in June of 1842.

The stories recounted above illustrate the diverse information that can be gleaned from federal records relating to slavery and emancipation in the District of Columbia. They show how the political and cultural upheaval of the Civil War era affected the lives of slaveholders, slaves, and free blacks. The abundant personal and historical information contained in these records make them a valuable resource for genealogical and scholarly researchers.

Damani Davis is an archivist in NARA's Research Support Branch, Customer Services Division, Washington, D.C. He has lectured at local and regional conferences on African American history and genealogy. Davis is a graduate of Coppin State College in Baltimore and received his M.A. in history at the Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio.

Notes

1 The D.C. Emancipation Act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on April 16, 1862. It granted the immediate emancipation of slaves, compensation to loyal Unionist slaveholders of up to $300 for each slave, and voluntary colonization of former slaves to colonies outside of the United States.

2 The April 16 Emancipation Act required that owners claiming compensation for their freed slaves file schedules for the slaves by July 15, 1862. A supplementary act of July 12, 1862 (12 Stat. 538) permitted submission of schedules by slaves whose owners had neglected to file, and it gave freedom to slaves whose owners lived outside of the District of Columbia if the slave had been employed with the owner's consent in the District any time after April 16, 1862.

3 The April 16 act stipulated that emancipation and compensation applied only to slaves working and slaveholders residing in the District of Columbia as of that date. Since the Addisons had fled three days before the act went into effect, there apparently was some initial uncertainty among the Soffells on whether they could lawfully claim the Addisons.

4 Records of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Relating to Slaves, 1851–1863, section 1 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M433), roll 1.

The proposition that the freed African American population should be somewhere outside of the United States, such as Africa, the Caribbean, or Latin America, was a very popular idea during this period. It was the subject of debate and was entertained by President Lincoln.

5 Mary Beth Corrigan, "Imaginary Cruelties?: A History of the Slave Trade in Washington, D.C.," Washington History: Magazine of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., 13 (Fall/Winter 2001–2002): 5.

6 Ibid., pp. 5–6; Hilary Russell, "Underground Railroad Activists in Washington, D.C.," Washington History, 13 (Fall/Winter 2001–2002).

7 See Dorothy S. Provine, District of Columbia Free Negro Registers, 1821–1861 (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 1996); Provine, Compensated Emancipation in the District of Columbia: Petitions under the Act of April 16, 1862, 2 volumes (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2008); Helen Hoban Rogers, Freedom & Slavery Documents in the District of Columbia 1792–1822: Bills of Sale, Certificates of Freedom, Certificates of Slavery, Emancipations, & Manumissions, 3 volumes (Baltimore: Gateway/Otterbay Press, 2007); and Jerry M. Hynson, District of Columbia Runaway and Fugitive Slave Cases, 1848–1863 (Westminister, MD: Willow Bend Books, 1999).

8 Records of the Board of Commissioners for the Emancipation of Slaves in the District of Columbia, 1862–1863 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M520, roll 6); Petition Nos. 29 and 741; Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury, Record Group (RG) 217; National Archives and Records Administration.

9 Records of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Relating to Slaves, 1851–1863 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M433, roll 1); Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21.

10 Ibid., roll 3. The deed of manumission for his wife Maria has his surname as "Sumerville," but he is listed in the 1860 census as "Sommerville." Eighth Census of the United States, 1860 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M653, roll 104); Records of the Bureau of the Census, RG 29.

11 Russell, "Underground Railroad Activists," Washington History, 13: 32–35. Recent scholarship suggests that Alfred Pope was actually his owner's (Congressman John Carter) nephew. If so, this relationship potentially explains the leniency of his owner, who simply accepted Pope back unto his estate and manumitted Pope when he died under the terms of his will. See Mary Kay Rick's, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 109, 353.

12 Records of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Relating to Slaves, 1851–1863, M433, roll 1.

13 Ibid., roll 3.

14 Habeas Corpus Case Records, 1820–1863, of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia (National Archives Microfilm Publication M434, roll 2), RG 21.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid., roll 1.