“Whitman, Walt, Clerk”

The Poet Was a Seer of Democracy and Bureaucracy

Winter 2011, Vol. 43, No. 4

By Kenneth M. Price

In April 2011, the National Archives announced the identification of nearly 3,000 documents written by Walt Whitman, one of the nation's greatest poets, while he served as a clerk in the federal government during and after the Civil War. The documents are in the records of the office of the Attorney General, now in the Department of Justice files.

Kenneth M. Price, professor of English at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, who discovered the documents while doing research at the National Archives, discusses their importance.

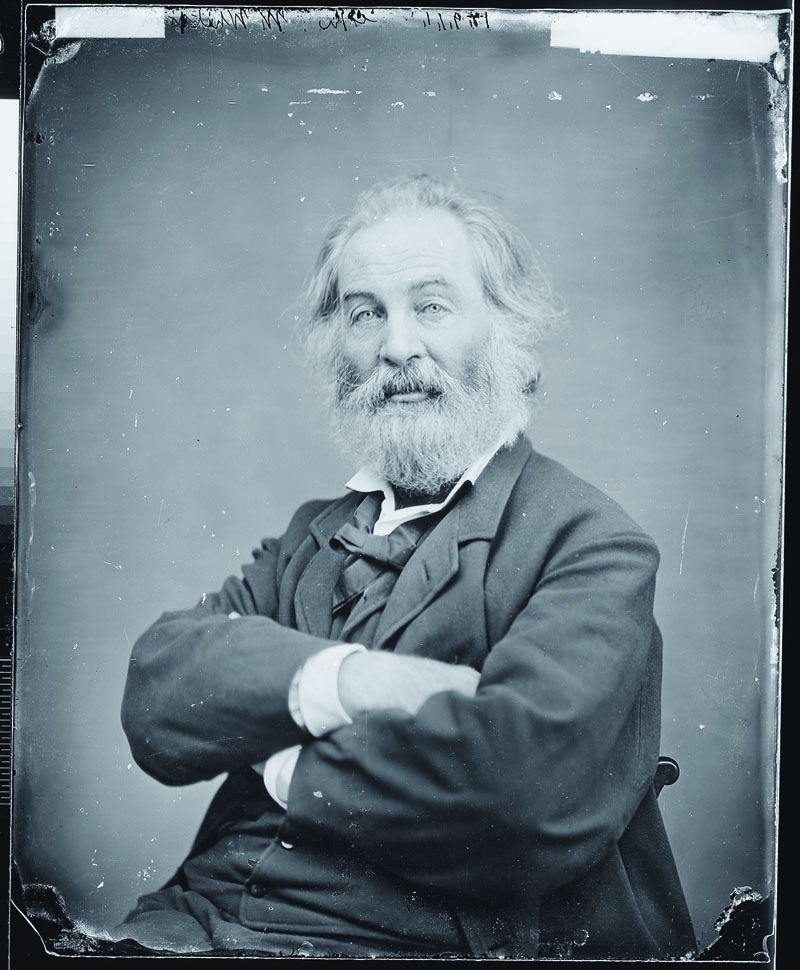

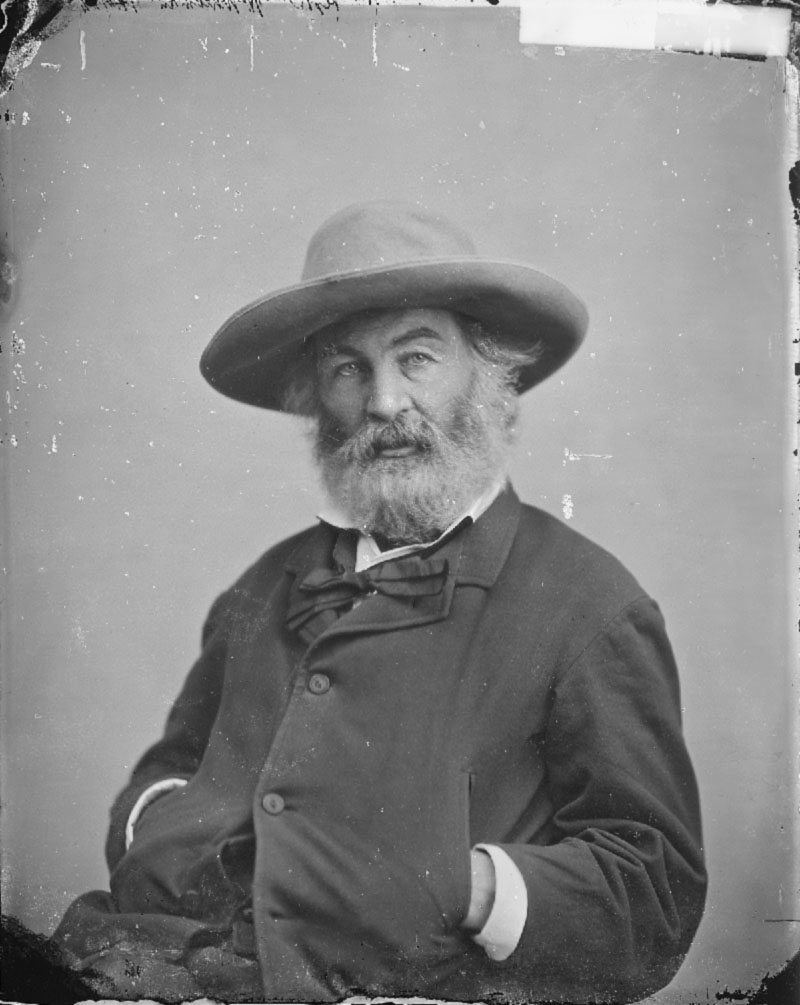

Walt Whitman's persona suggested he was relaxed, perhaps even slightly lazy—after all, the speaker in "Song of Myself" is content to "lean and loafe" at his ease, observing a spear of summer grass.

Yet during Whitman's decade in Washington, 1863–1873, he labored intensely, at times seeming to have three lives going at once. He wrote perhaps the most moving and memorable of all Civil War poetry, Drum-Taps (1865), later folded into his best-known work, Leaves of Grass. In addition, he cared for tens of thousands of wounded and sick soldiers in Washington, D.C., hospitals, serving as an attentive visitor.

Finally, Whitman also secured and maintained employment as a low-level government clerk, a position that enabled him to support himself and his hospital efforts. Over the years, Whitman's roles as poet and caregiver have been of such great interest that his government work has been all but disregarded.

The recent identification of nearly 3,000 documents in his handwriting in the National Archives leaves us now better able to study Whitman's life in its full complexity and to reevaluate his literary accomplishments. The world of bureaucracy contributed to the poetry of democracy in ways we can only now begin to study.

It will take years, perhaps even decades, for scholars to fully explore this trove of documents. However, it is possible, even at this stage, to put this find in context and offer some preliminary observations.

"I do not see that I do much good to these wounded and dying."

A New Yorker by birth, Whitman first came to the Washington, DC, area in December 1862, following the battle of Fredericksburg. He had rushed to the front to check on his brother George, whose name had appeared on a casualty list. Once assured that his brother would be fine (he had a superficial cheek wound), Whitman began aiding the many seriously wounded men as they were transported to Washington. In the following years he visited the dozens of hospitals that sprang up everywhere in the capital (all types of structures were adapted to accommodate the wounded, including a blacksmith's shop).

He visited soldiers from both north and south, to whom he dispensed oranges, stationery, small amounts of cash, candy, bread pudding, and love. He was a sustaining presence to many frightened young men suffering from amputations, dysentery, smallpox, and a variety of other debilitating wounds and ailments. The urgency of the times is captured in the poet's October 13, 1863, letter to his mother, Louisa Van Velsor Whitman:

There is a new lot of wounded now again. They have been arriving, sick & wounded, for three days—First long strings of ambulances with the sick. But yesterday many with bad & bloody wounds, poor fellows. I thought I was cooler & more used to it. . . . I had provided a lot of nourishing things for the men, but for another quarter—but I had them where I could use them immediately for these new wounded as they came in faint & hungry, & fagged out with a long rough journey, all dirty & torn, & many pale as ashes, & all bloody—I distributed all my stores, gave partly to the nurses I knew that were just taking charge of them—& as many as I could I fed myself—Then besides I found a lot of oyster soup handy, & I procured it all at once—Mother, it is the most pitiful sight I think when first the men are brought in—I have to bustle round, to keep from crying—.

At times Whitman wondered if his labors did the men any good: "I do not see that I do much good to these wounded and dying," he wrote; "but I cannot leave them." After the war several soldiers credited Whitman with saving their lives.

Yet, the Washington city directory listed him not as "national poet" nor as "missionary to the wounded" but instead as "Whitman, Walt, clerk." He functioned primarily as a secretary of the day, spending much of his time as a scribe or copyist. Beginning in 1863, he worked in the Army paymaster's office and for the Bureau of Indian Affairs before gaining a clerkship in the attorney general's office.

All of the documents I have identified were in records of the attorney general's office and date from 1865 to 1873. These records are now filed as Department of Justice records, though that department did not exist when Whitman began his employment.

As noted, although Whitman's work as a clerk spanned a significant number of years, it has received surprisingly little attention from biographers. In 1943, Dixon Wecter published a valuable article on "Walt Whitman as Civil Servant." No one has followed up on his work in any significant way, perhaps because Wecter made no estimates about the number of documents in Whitman's handwriting. In fact, the article discusses about a dozen items but never implies that there are a vast number of other documents to be explored.

When scholars have described Whitman's government work, they suggest he took things casually, sauntered into work when he wanted to, put in a few hours, and left when it suited him.

The evidence I have collected paints a very different picture. He worked steadily and produced a prodigious amount of material. Or as Whitman himself told Horace Traubel, a friend who left a record of the poet's late-in-life conversations: "It is a great mistake to suppose the positions all or mostly sinecures—some of the clerks work like beavers."

Those above him in the attorney general's office valued the clarity of his handwriting (it is outstanding) and the quality of his intellect. In 1866, for example, Attorney General James Speed wrote to J. Hubley Ashton, his assistant attorney general, letting him know of plans to dedicate a bust of Abraham Lincoln in Speed's home town of Louisville, Kentucky. Too busy with other obligations to complete his speech, Speed asked Ashton to "see our friend Walt Whitman and ask him whether he will take my rough draft of an address and revise and finish it. . . . I have a notion that if he has the time and is in the mood he can do it better than any man I know."

While Building an Archive, a Gold Mine is Discovered

The full extent of these government documents only recently came to light because of the work of the Walt Whitman Archive, a project I co-edit with Professor Ed Folsom of the University of Iowa. This freely available resource sets out to make Whitman's vast work, for the first time, easily and conveniently accessible to scholars, students, and general readers.

In our ongoing search for documents, it occurred to us that there might possibly be a few additional instances of Whitman's work as clerk from 1863–1873 still surviving somewhere in government records. I made an initial trip to the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, hoping to find four or five documents in Whitman's handwriting.

My first day of searching was initially disappointing, as I turned over hundreds of documents and found nothing in Whitman's distinctive handwriting. (Previous work on Whitman manuscripts left me confident that I could pick out his hand as if it were that of a close relative.)

Then suddenly I turned a page in one of the vast letter books containing office copies of outgoing correspondence, and there it was: an entire page in Whitman's hand. Then a few more documents in the handwriting of other clerks, and then I found a whole string of documents entirely in Whitman's handwriting. I was astonished to find several hundred documents that first day. And over another eight trips to Washington, I located thousands more.

Preserving the Records: Margin Notes and All

What will happen to these documents?

The Walt Whitman Archive will present high-quality color facsimile images of these documents, along with searchable transcriptions. The facsimile images are especially important since not more than a handful of these documents are signed or initialed by Whitman. One of the few documents that is initialed appears here. It is a July 14, 1868, letter in Whitman's hand having to do with pensions. A marginal note, also in Whitman's hand, says: "This letter has been withdrawn and cancelled—is to be considered as never having been written. W.W." The practice of canceling a document is straightforward. However, the phrasing here is curious, perhaps even nonsensical. How can one look at writing and regard it as never having been written?

Intriguingly, the comment serves as an apt description of how Whitman's work as a scribe has been treated—as cancelled, non-consequential, writing that somehow left no mark either on the writer or the world.

Actually, these documents have double significance both because they contributed to national redefinition in the aftermath of civil war and because of Whitman's role in their creation. For the most part, the documents I have located were internal fair copies of outgoing correspondence. These were kept for reference purposes—as a record of orders, instructions, and policies.

Interestingly, in a case dealing with a murder in Dakota Territory, we can compare one of apparently several external copies with the internal office copy. The letters are nearly identical in semantic content, although they are visually quite distinct because they were written by two different scribes.

In addition, in this case the external copy has with it illuminating contextual information not found with the office copy. It is unclear how many other documents in Whitman's handwriting might be found across the country if a systematic search were to be conducted for the external or sent copies. Presumably, the information in these copies would duplicate what we have in the internal copies of record.

At the Walt Whitman Archive, You Can Judge for Yourself

The identification of almost all of the documents, with the exception of the few that bear Whitman's initials, depends on recognition of his handwriting, and it is important to provide the evidence in full. These documents are being mounted in an online environment containing previously known pieces of signed correspondence. Users are welcome to judge for themselves the authenticity of the documents.

All material that we present—Whitman's poetry, prose, photographs, personal correspondence, scribal documents, and more—is made freely available to a world audience. We are able to do this thanks to support from four different universities and grants from various federal agencies including the Institute of Museum and Library Services and the National Endowment for the Humanities. For the discovery described here, we are indebted to the National Historical Publication and Records Commission (NHPRC), the publishing arm of the National Archives. Their support enabled us to publish the first 800 of the newly discovered scribal documents in fall 2011, with the remainder scheduled for the following year.

Should these documents be dismissed because Whitman was not the sole "author" of them in the typical sense? Actually, it is not clear how much he contributed to many of the letters he copied. We have to wonder how many of these documents may have been created in the manner James Speed described, with a capable clerk left to "revise and finish it."

With regard to any one particular document we can only speculate about how Whitman might have served as author or copyist or both. Regarding the overall working of the office, we do have Whitman's description given in conversation with Horace Traubel: Whitman said he had been "put in charge of the Attorney General's letters." In this instance, Whitman did not specify which one he meant of the several attorneys general he served, perhaps implying that it was a common practice for them all.

Whitman continued by saying: "cases were put into my hands—small cases: the Attorney General could not attend to them all so passed some of them over to me to examine, report upon, sum up."

At other times, Whitman is more specific in his remarks to Traubel, as in these comments about Henry Stanbery, the attorney general under Andrew Johnson, before Stanbery stepped down in order to defend Johnson during his impeachment.

"I was the Attorney General's clerk there," he said, "and did a good deal of writing. [Stanbery] seemed to like my opinions, judgment. So a good part of my work was to spare him work—to go over the correspondence,—give him the juice, substance of affairs—avoiding all else."

Whitman's proximity to Stanbery and President Andrew Johnson is seen dramatically in a letter reproduced here, a letter written entirely— including the signature "Andrew Johnson" —in Whitman's hand.

At the end of this conversation about Stanbery and Johnson, Traubel told Whitman that probably some day, his department books (i.e., his work in the attorney general's office) would be "curiously examined." Traubel could not have been more prescient.

Although many of Whitman's friends who held positions as clerks complained about their work, Whitman did not. He rather enjoyed the work in part no doubt because he was dealing with intellectually engaging material. He also liked and admired the people he worked with. A conversation recounted by Traubel is again revealing:

Some discussion of officialdom in Washington, W. arguing: "From my experience at Washington I should say that honesty is the prevailing atmosphere." Somebody laughed. W. stubbornly resumed: "Let me explain that. I do not refer to swell officials—the men who wear the decorations, get the fat salaries (they are mostly dubious enough, though not all): I refer to the average clerks, the obscure crowd, who after all run the government: they are on the square. I have not known hundreds—I have known thousands—of them. I went to Washington as everybody goes there prepared to see everything done with some furtive intention, but I was disappointed—pleasantly disappointed. I found the clerks mainly earnest, mainly honest, anxious to do the right thing—very hard working, very attentive. Why, the clerk jobs are often the worst slavery: the clerks are not overpaid, they are underpaid. Washington is corrupt—has its own peculiar mixture of evil with its own peculiar mixture of good—but the evil is mostly with the upper crust—the people who have reputations—who are better than other people."

In this case, Whitman praises clerks at the expense of the "upper crust," but at other times, he showed admiration for government workers at all levels. Speaking of the many letters that were lost because they were poorly addressed and also of the trivial correspondence that came into government offices, Whitman told Traubel:

People have more conscience in such things than is known, believed,—even having in those cases [of erroneously addressed letters] made efforts to find the owners. It was so in the departments, too—the chiefs were very accommodating for instance, in the answering of letters, some of them verging on idiocy—yet all conscientiously consulted, replied to. I have known this not in the case of the clerks alone, but have known heads of departments with whom it was a principle.

Whitman Worked for Government While Revising Leaves of Grass

Whitman's experiences in Washington offices have rich implications. In Washington, Whitman was an actor near the epicenter of government efforts to reshape the nation in the aftermath of war.

We can now pinpoint to the exact day when he was thinking about certain issues. Some of these documents treat routine administrative matters (e.g., appointments of officials, salary payments, and book orders) but others treat civil rights, war crimes, treason, western expansion, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, and a host of international incidents. He treated closely related matters while revising Leaves of Grass and drafting Democratic Vistas, his probing analysis of the condition and prospects of the United States. Democratic Vistas is one of the most penetrating assessments of American culture ever written, and scholars will now be able to study how his analysis was informed by in-depth knowledge gained in the attorney general's office.

His network of friendships in Washington offices also shaped his ability to get various government jobs during his decade in Washington, and it influenced his literary writings.

For example, Whitman sent a copy of his "Proud Music of the Sea-Storm," published in the Atlantic Monthly in February 1869, to an acquaintance named Julius Bing, a clerk of the Joint Select Committee on Retrenchment in 1867 and 1868. In response, Bing wrote a lengthy letter urging Whitman to write a poem about the Child Crusades.

The poem was attempted by Whitman but never realized as such (Whitman's notes on the topic and trial lines can be found in the Thomas B. Harned Collection of the Library of Congress). To the best of my knowledge, this aborted poem has not received any critical commentary, but I think it is well worth study because it is a rare instance of Whitman, in effect, collaborating on a poem, and it also shows him addressing an international issue of the remote past, but one with continuing resonance in his time and in our own.

Newly Found Records Provide Fresh Insights into Whitman

Imagining a firm wall dividing Whitman's creative life and his life as a clerk is misleading. At times, Whitman used his office address as his literary postal address, and he worked in the office at night (the heat and lighting were important benefits). Moreover he first gained his clerkship with the help of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who recommended him on literary and patriotic grounds.

And it was because Whitman's Blue Book (his personal and very heavily revised copy of the third edition of Leaves of Grass) was found at his government desk that he lost his job at the Bureau of Indian Affairs. James Harlan, the secretary of the interior, judged the book to be immoral, though Whitman's allies staunchly defended it and helped him to secure a new post in the attorney general's office.

During his Washington years, Whitman's literary and clerical lives regularly occurred in the same physical locations and no doubt in related emotional and psychological circumstances.

As recently as 1998, one commentator, Luke Mancuso, noted that "The Reconstruction [era] Whitman remains the Whitman who has yet to be fully scrutinized by . . . scholars and readers alike." That comment was made with reference to writings known then. With the recent announcement of a large trove of previously unknown manuscripts, the Reconstruction era has a much richer archive of Whitman materials with which to advance knowledge and enable a whole array of new interpretations.

Kenneth M. Price is Hillegass University professor of English at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. He is the co-director of the Walt Whitman Archive and the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities.

Note on Sources

The newly discovered documents are in Records of the Office of the Attorney General, 1790–1870, General Records of the Department of Justice, Record Group 60, National Archives at College Park, MD. Direct quotations from Walt Whitman are from his letters in the Walt Whitman Archive.

Dixon Wecter discussed Whitman's work as a government clerk in "Walt Whitman as Civil Servant," PMLA 58 (December 1943): 1094–1109. There is also evidence that in some cases Whitman was called on to summarize legal documents.

Rosemary Graham mistakenly argues that "for the most part . . . Whitman spent these postwar years as an observer." See "Attorney General's Office, United States," in Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia, ed. J. R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings (New York: Garland, 1998).

The quotations recorded by Horace Traubel are published in With Walt Whitman in Camden, 9 vols. (various publishers, 1906–1996).

M. Lynda Ely, "Memorializing Lincoln: Whitman's 'Revision' of James Speed's Oration Upon the Inauguration of the Bust of Abraham Lincoln," Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 14 (Spring 1997), p. 176.

Julius Bing (dates unknown) served as the clerk of the Joint Select Committee on Retrenchment in 1867 and 1868 and ghostwrote the 1868 report "Civil Service of the United States" before being appointed diplomatic agent for Crete later that year. A major advocate for reform of the Civil Service, Bing wrote a series of articles on the civil service for the North American Review and Putnam's Magazine in 1867–1868. For more on Bing, about whom little is known, see Art Hoogenboom, Outlawing the Spoils: A History of the Civil Service Reform Movement 1865–1883 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1968), especially pp. 40–49.

Ralph Waldo Emerson's January 10, 1863, letter of recommendation addressed to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase is in Whitman's personnel file in General Records of the U.S. Treasury, Record Group 56, National Archives at College Park, Maryland. The Whitman Archive has transcriptions of that letter and for the letter to William H. Seward on the same date.

Luke Mancuso's comment about the Whitman "who has yet to be fully scrutinized" is found in his article "Reconstruction" in Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia, ed. J. R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings (New York: Garland, 1998), p. 577.