The A-Files

Finding Your Immigrant Ancestors

Spring 2013, Vol. 45, No. 1

By Elizabeth Burnes and Marisa Louie

During a 1940 radio public service announcement (PSA), Attorney General Robert Jackson said that “a year-end inventory of assets is a customary procedure of sound business.”

He was referring to an “inventory” of all aliens living within the United States between April 27 and December 26, 1940.

“They are not American citizens but, with relatively few exceptions, these foreign-born among us are American assets—precious human assets,” Jackson said. “At this critical period of our history an accounting of our assets is more than just sound practice; it is absolutely essential to our national defense.”

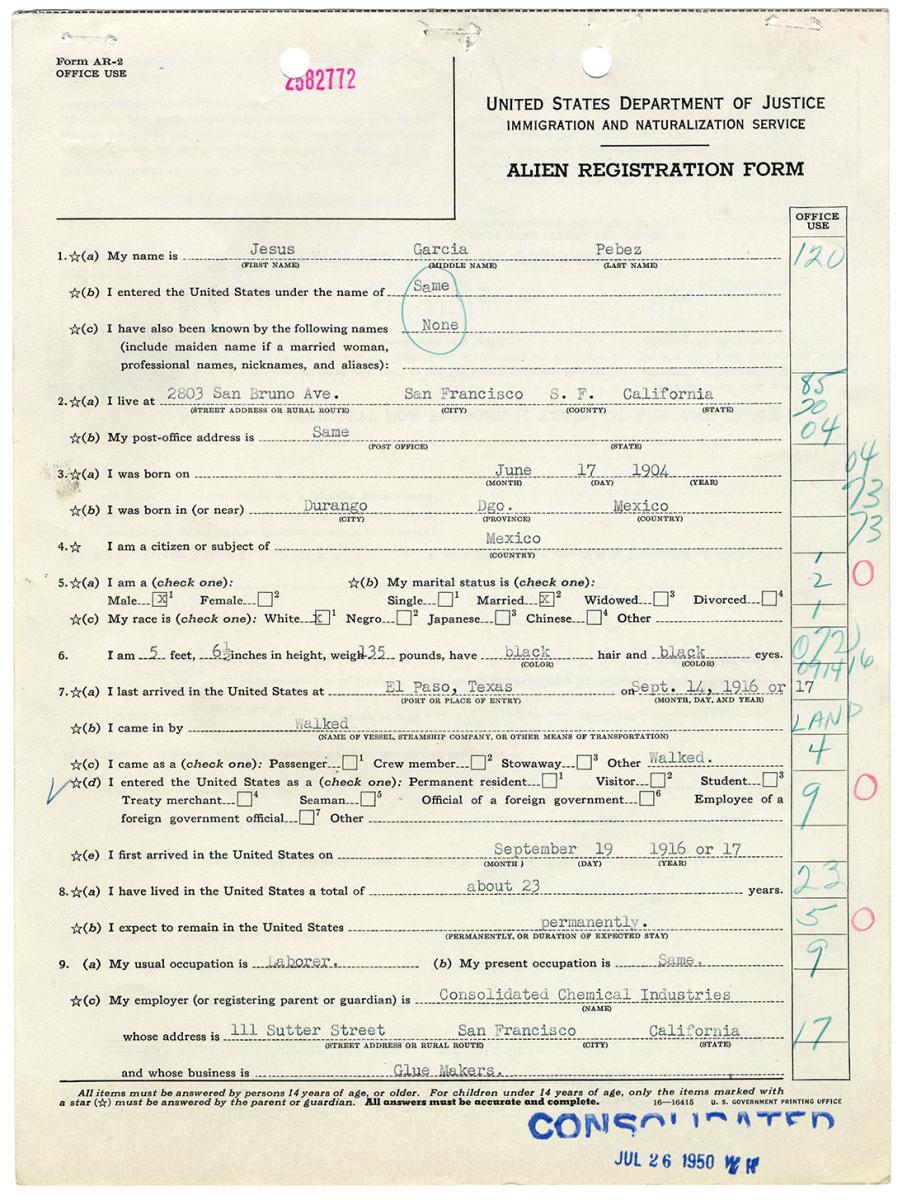

The Alien Registration Act of 1940 required that all persons who were not citizens or nationals of the United States and were living within U.S. borders go to the local post office and register their alien status with the government. The registration process included filling out a questionnaire and having fingerprints taken. Certain exclusions applied for diplomats, employees of foreign governments, and children under the age of 14. The Alien Registration Form (Form AR-2) contained 15 questions. These included questions about when and where the subject was born, when and where he or she entered the United States, and a physical description. There were also questions about employment, organization memberships, prior military service, and attempts to obtain naturalization in the United States. As the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) received the forms, it assigned an Alien Registration Number (for example, A1234567). The INS mailed an Alien Registration Receipt Card with this number to each registrant as proof of alien status.

A series of radio PSAs promoted registration. The PSAs said participation supported democracy and called on Americans to aid their alien neighbors in completing the registration process. A number of officials of foreign descent—German, Italian, Polish, etc.—spoke to audiences in their native tongues to ease fears about the registration restricting or violating their rights. To bolster support, newspapers across the country published numerous photographs of actors and musicians who were aliens completing the registration process.

Government officials expected around 3.6 million registrants, but final counts saw more than five million forms submitted. The completed AR-2 and the correlating A-Number became the foundation on which the Alien Files (A-Files) were later built.

In 1944, INS recordkeeping moved from separate systems among field offices to a more standardized and structured approach. Beginning in April 1944, the new A-Files became the home for many of the Alien Registration Forms. The files, which were arranged by the A-Numbers assigned during the 1940 registration, tracked the interaction between an alien and the U.S. government leading up to naturalization, permanent residency, or deportation. The Alien Registration Form was often the first form transferred into the file.

Since 1944, more than 60 million A-Files have been created, but not every alien received a file in the early years of this filing system. Normally a file was opened when an action was taken by the alien to obtain a benefit from the federal government. For example, an alien might file a petition for an immigrant relative or a replacement for a lost alien registration card. A law enforcement case involving the alien could also prompt creation of a file.

Until April 1, 1956, the INS created Certificate Files (C-Files) to consolidate and manage documentation issued during the naturalization process. Any existing alien-related documentation (including the Alien Registration Form) was consolidated into a C-File. After April 1, 1956, the INS no longer created C-Files, and all documentation related to an alien was consolidated into an A-File. Today, the A-Files per- sist as the singular consolidated files for all records related to immigration, inspection, and naturalization processes.

Because of these changes to INS filing systems over time, an immigrant to the United States may have an A-File, a C-File, or another type of record created by INS. When determining whether the person you are seeking has an A-File, consider the following:

| THE IMMIGRANT . . . | |

| Died before August 1, 1940 | Will not have an A-File or an Alien Registration Number. Research other National Archives resources of genealogical interest. |

| Became a naturalized citizen between September 27, 1906, and August 1, 1940 | Will not have an A-File or an Alien Registration Number. Inquire with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) Genealogy Program regarding a possible Certificate File (C-File). |

| Became a naturalized citizen between August 1, 1940, and March 31, 1956 | May or may not have an A-File. Also inquire with the USCIS Genealogy Program regarding a possible C-File or 1940 Alien Registration Form. |

| Immigrated to the United States after April 1, 1944 | Will have an A-File. Check National Archives holdings if born in 1910 or earlier. Otherwise, inquire with the USCIS Genealogy Program. |

| Naturalized on or after March 31, 1956 | Will have an A-File. Check National Archives holdings if born in 1910 or earlier. Otherwise, inquire with the USCIS Genealogy Program. |

| Registered in the United States as an alien in 1940 but never came back to the Immigration and Naturalization Service for any reason | Was likely assigned an Alien Registration Number but will not have an A-File. Check with the USCIS Genealogy Program for a copy of the 1940 Alien Registration Form. |

| Registered in the United States as an alien in 1940 and came back to the Immigration and Naturalization Service for any reason (other than naturalization) after 1944 | Will have an A-File. Check National Archives holdings if born in 1910 or earlier. Otherwise, inquire with the USCIS Genealogy Program. |

How Did the A-Files Come to the National Archives?

In the past, the National Archives sought to retain records that contained information that would help future historians understand “governmental organization, functions, policies, and activities.”

“Personal data records” were not always considered “permanent.” The National Archives formed the Person- al Data Records Task Force in 1995 to examine several record series, including the A-Files, which had been previously scheduled as 75-year temporary records.

The A-Files were of particular importance to the Asian American community in San Francisco. The National Archives at San Francisco holds hundreds of thousands of case files relating to Chinese immigrants and Americans of Chinese descent, dating to the period of the Chinese Exclusion Acts.

Genealogists using these case files often found gaps because older immigration records may have been consolidated into an A-File. While these researchers were able to get copies of the A-Files through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and Privacy Act requests to the INS, they began to advocate for the permanent retention of the A-Files at the National Archives.

Also in the mid-1990s, the National Archives created a team to study storage limitations in all its facilities. A consortium of community and genealogical organizations, Save Our National Archives (SONA), first formed to “save” the California, on regional facilities from consolidation or closure, turned its October 14, 1940. energy to preserving the A-Files.

Plans for a centralized records facility for the A-Files in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, brought more calls to reevaluate the files as permanent records. SONA, with the backing of California Congressman Tom Lantos, requested that the A-Files maintained in the Federal Records Center in San Bruno, California, be withheld from centralization.

The INS and the Archives agreed to keep these A-Files in place for further study about their research value and their relation to records already in the permanent holdings of the National Archives. These A-Files had been maintained by INS District Offices in San Francisco; Reno, Nevada; Honolulu; and Agana, Guam. A-Files from all other Federal Records Centers around the United States—approximately 350,000 cubic feet of material—were moved to the INS’s National Records Center in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, in 1998 and 1999.

For the next decade, the INS—which would become U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in 2003—and the Archives continued to discuss how to retain the A-Files as permanent records. On June 3, 2009, representatives of the Archives and USCIS signed a new records schedule to officially designate all A-Files as permanent historical records. The records schedule now authorizes USCIS to send A-Files to the National Archives 100 years after an immigrant’s year of birth.

The National Archives at Kansas City opened its holdings of eligible A-Files from the USCIS National Records Center in Lee’s Summit on September 1, 2010. The National Archives at San Francisco opened its holdings of eligible A-Files—drawn from those originally retained in the San Bruno Federal Records Center—on May 22, 2012.

How Can I Use the A-Files for Genealogy Research?

A-Files can contain a wealth of genealogical data, including visas, photographs, applications, affidavits, and correspondence. Although the first files were created in 1944, documents and information may be much older. Documents may also refer to any final action related to the alien, which could be deportation, permanent resident status, or citizenship. The files can contain demo- graphic information and documents that may not be found elsewhere, such as lists of places of residence, or baptismal certificates.

One person’s file may contain only the Alien Registration Form and an Address Report Card, while another may have hundreds of pages, including applications, interview transcripts, letters of reference, handwritten notes, and family photographs. For a few lucky researchers, the A-Files can be a one-stop shop. For everyone, however, the files are another great piece of the puzzle. Genealogists can obtain basic biographical information and jumping-off points for filling in gaps in research they’ve already done, doing further research, and in some cases locating previously unavailable documentation.

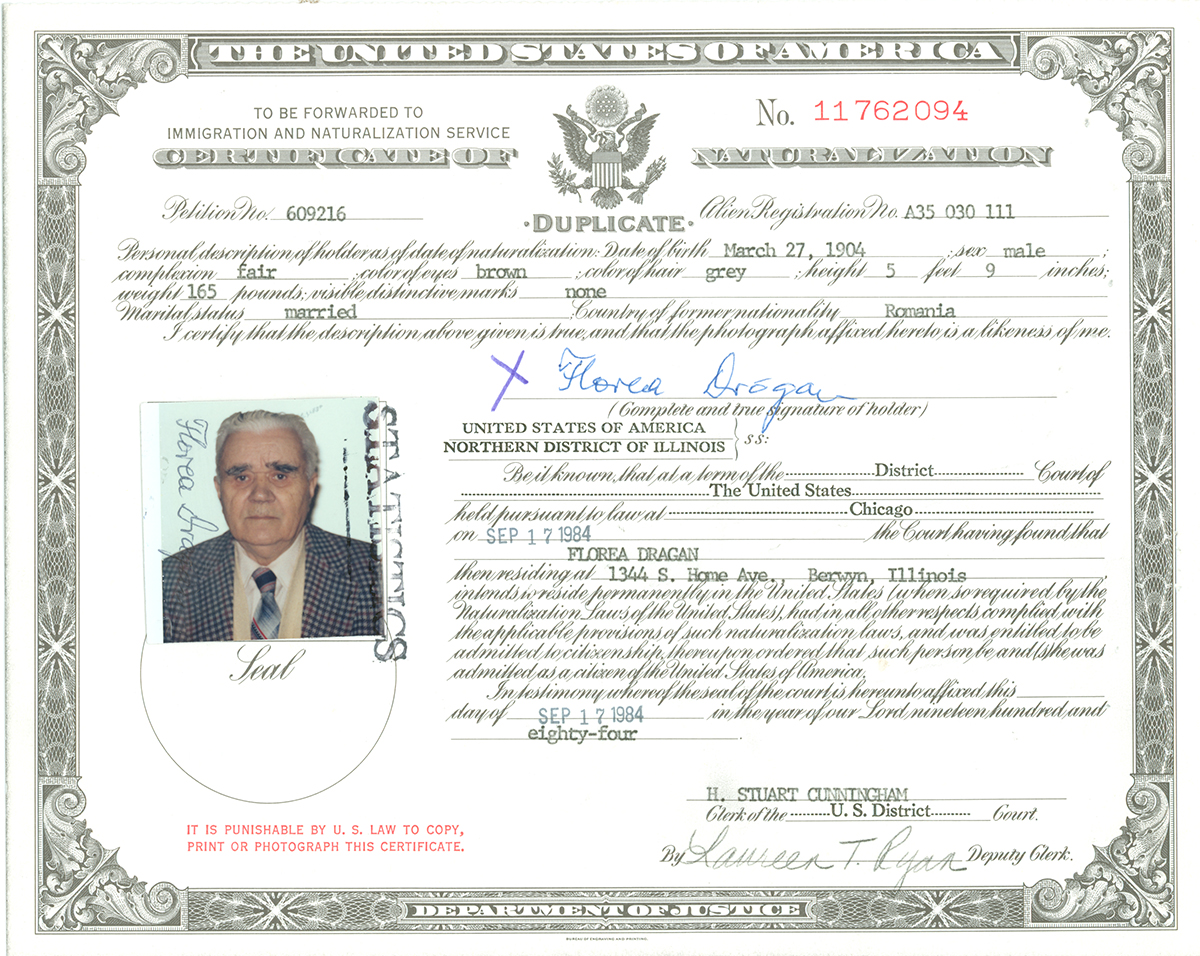

Certificate of Naturalization

Finding a Certificate of Naturalization can be quite exciting for genealogists because it provides both proof of citizenship and a photograph of the individual. Only two copies of a Certificate of Naturalization ever existed—the copy presented to the petitioner when citizenship was granted, and a second copy maintained by the INS in either a C-File or A-File.

Certificates of Naturalization are a rare find outside of immigration files, but researchers should check among family papers. Finding the original copy of a certificate can help with the A-File search because the A-Number is sometimes printed on the certificate. As the naturalization process evolved, documentation of the process leading to the certificate changed. During the 1960s the Petition for Naturalization filed in the court became more abbreviated, so the extended Application for Naturalization—which is found in the A-File—becomes a more useful source for detailed biographical information.

Address Report Card

The Alien Registration Act of 1940 required all aliens to report their address on a regular schedule, and all changes of address were to be reported within five days to avoid penalties. The Address Report Card form changed throughout the 1940s and 1950s. At its most basic, the form gathered the individual’s name, address, A-Number, and the date. Although the card is sometimes dis- missed as less helpful than other documents in an A-File because the information recorded is limited in scope, it does allow researchers to obtain information about residences in non-census years.

Immigrant Visa and Alien Registration

The Immigrant Visa and Alien Registration combined the registration and visa procedures into a single component and replaced the Alien Registration Form used during the 1940 registration. It records much of the same information but gathers a significant amount of additional content, including details of family members (parents, children), prior residences and travel, and prior employment. The attachments to this form often draw the strongest reaction from genealogists. Attachments most frequently consist of a birth certificate, marriage certificate, and a police report from the country of origin. Occasionally, baptismal and death certificates ap- pear, and sometimes certificates for parents, spouses, and children. This form and its attachments can be a treasure, but it appears in only a small percentage of A-Files.

How Do the A-Files Relate to Existing National Archives Holdings?

The Chinese Exclusion Act–era immigration case files (Record Group 85) pre-date the A-Files. These case files, which document the arrival and travels of persons of Chinese descent, may contain references to A-Files in the form of an INS charge-out slip or an annotated file jacket. Researchers should note the Alien Registration Number (A-Number) and use this to search National Archives A-Files holdings.

The Petition for Naturalization for someone who became a citizen after March 31, 1956, can be used to search for an A-File. Petitions may be found in the records of the U.S. District Courts (Record Group 21) or in the records of local county or state courts.

What Resources are Available Outside the National Archives?

If you discover that the National Archives does not have the A-File you are seeking, you can continue your search by contacting U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services through its Genealogy Program. The USCIS holds all active and inactive A-Files that have not yet been transferred to the National Archives.

In addition, the USCIS has a number of other file types useful for genealogy: Certificate Files (C-Files) from September 27, 1906, to April 1, 1956; Alien Registration Forms from August 1, 1940, to March 31, 1944; Visa files from July 1, 1924, to March 31, 1944; Alien Files (A-Files) numbered below 8 million (A8000000) and documents therein dated prior to May 1, 1951; and Registry Files from March 2, 1929, to March 31, 1944.

The USCIS Genealogy Program offers two primary ser- vices for researchers—an Index Search and a Record Copy Request. For a fee, USCIS staff will search its historical indexes for file citations related to an individual. The search will identify all relevant files and explain how to request copies of the records. Researchers pursuing dual citizenship should note that the USCIS cannot certify documents, but they can provide certification of non-existence of a record (or no naturalization record) of deceased immigrants.

How Have Researchers Used the A-Files?

Start the search for a particular A-File in the National Archives’ Archival Research Catalog (ARC). Search ARC by first name, surname, or by A-Number. Requests for A-Files should include the full name of the alien, the ARC Identifier (also known as National Archives Identifier), and the A-Number. Archives staff can help you with this process if you do not have access to a computer.

Since the files were first opened in late 2010, the regional archives at Kansas City and at San Francisco have received nearly 1,000 requests for information from the A-Files.

Family historians, authors, journalists, and demographic historians have discovered that the snapshot of a life captured in the files is priceless. Stemming from the original “inventory” in 1940, the documentation of our foreign-born ancestry through the A-Files has evolved and opened up new avenues for understanding the past.

Related stories:

- An A-Files Advocate

- Piecing Together the Puzzle: A Holocaust Survivor’s A-File

- A Life Imagined: The A-File of Umeyo Kawano

Elizabeth Burnes is an archivist at the National Archives at Kansas City. She received a bachelor’s degree in history from Truman State University and a master’s in history and museum studies from the University of Missouri at St. Louis.

Marisa Louie is an archivist at the National Archives at San Francisco. She was formerly the Program Coordinator at the Chinese Historical Society of America and is an alumna of the “In Search of Roots” Program. She holds a bachelor’s degree in American studies and environmental studies from the University of California at Santa Cruz.

Learn more about:

The A-Files and how to the request them

The evolution of the A-Files, see Paul Wormser’s 1995 paper, “Documenting Immigrants: An Examination of Immigration and Naturalization Service Case Files”