The Declaration of Independence and the Hand of Time

Fall 2016, Vol. 48, No. 3

By Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler and Catherine Nicholson

Every year, more than a million visitors come to the National Archives Building in Washington, DC, to see the Declaration of Independence.

Sometimes you can see them in the Rotunda, patiently waiting for a good position in front of the encasement containing the Declaration. They bend low over the glass to try to make out the faint script and identify the names of the signers.

The Declaration continues to instill a sense of awe. But the physical document itself has suffered greatly over the years. Its legibility is greatly diminished, and the document today is much different in appearance from when it was penned in 1776. Compared to the legibility of the U.S. Constitution (1787) and Bill of Rights (1791), which are only slightly more recent, the differences are startling.

So what happened to this revered document?

There is little written evidence of what may have happened—or when—to alter the document. However, by piecing together the history and travels of the Declaration, and by examining key photographs, we can answer some questions about how the document got to its current state.

Creating the Physical Document

After Declaring Independence

On July 19, 1776, the Continental Congress ordered the Declaration of Independence to be engrossed—or written out in a large legible hand. Timothy Matlack, a clerk in the Pennsylvania State House, was the scribe charged with this task. Matlack’s work included laying out the text on the parchment, determining the margins and space between lines, and calculating the space that would be needed at the bottom of the document for signatures.

Between July 19 and August 2 (when delegates began to sign the document), Matlack wrote out the text on a large sheet of parchment. He selected the best skin that was available, prepared his quill pens, and made sure he had a sufficient supply of ink.

Matlack penned a new title that is visually distinctive, with large letters and flourishes: “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.” Under this title, the lines of text take up almost the entire width of the parchment.

Though not a perfect rectangle, the parchment is close at about 29½ by 24 inches. It was slightly larger in Matlack’s day, as evidenced by variation in clean and dirty edges, especially along the top edge of the skin. Extremely grimy edges, resulting from years of handling the bare parchment, are original and reflect the full dimension of the document, while cleaner edges are evidence of trimming at some time in the past. Why would edges have been trimmed? The possibilities include the desire to tidy an uneven edge, the need to remove a jagged bit of parchment that could catch on something and tear, or the wish to straighten an edge before mounting the document for exhibit.

Iron Gall Ink,

Nice Straight Lines

Iron gall ink, the kind typically used in Matlack’s day, included tannic acid (from oak galls), iron (from nails or iron scraps), a binder (often gum arabic), and sometimes a colorant. Light in color when it was applied, the ink darkened as it oxidized to an intense purplish black. Over time, iron gall inks age to a warm brown.

Matlack’s lines of text are quite straight. Scribes often made pin pricks in the margins and drew rule lines across the sheet to guide the pen. There is no evidence today in the text of either pin pricks or rule lines. Of course, lightly applied rule lines could have disappeared as a result of handling and abrasion.

The signature area, however, has vertical rule lines that served to align signatures in columns. These light grey rules lines are faint. But if you look very closely—to the left of columns one through four and to the left of column six, you can see them.

Relatively little original ink remains today on the Declaration. Many factors contributed to this loss. In areas of heavy ink application, for example in the title and in some signatures, ink flaked off as a result of repeated rolling and folding of the document.

A decrease in the intensity—and thus the legibility—of the ink can also be attributed to prolonged exposure to light during exhibition, which resulted in some fading. In addition, moisture applied to the document during wet-transfer copying processes would have removed some amount of ink. The text that we see today is changed in appearance as a result of these collective actions.

Early Travels with Congress

Rough on the Declaration

The Declaration traveled with the Continental Congress as it moved by land and by water during the Revolutionary War. In 1789, under the custody of the new Department of State, it continued to travel as the capital moved.

The single sheet of parchment could have been rolled for transport or, just as likely, folded to fit into a saddle bag or a wooden chest. The primitive conditions of packing and transport under which it traveled with other documents were perilous and exposed the parchment to radical changes in temperature and relative humidity.

These changes left their mark. Evidence of previous folding and rolling is still visible on the Declaration: two primary vertical fold lines run from top to bottom, and there are numerous horizontal fold lines especially in the lower part of the document. Small creases or crimps overall on the parchment resulted from rolling the document into a tight diameter, and some creases would have resulted from the parchment being crushed or flattened while rolled. The Declaration was rolled starting at the top edge, toward the text. This would protect the text from the elements and handling, leaving the blank skin as the outer layer. An inscription written near the bottom of the back of the parchment that read “Original Declaration of Independence dated 4th July 1776” acted as an identifying label.

Reproducing the Declaration

So All Could See It

At the end of the War of 1812, very few people had actually seen the Declaration. The idea of creating printed images of the Declaration was in the air.

Penman and calligraphy teacher Benjamin Owen Tyler created an embellished calligraphic text of the Declaration and had it engraved by Peter Maverick, with facsimiles of all the signatures below.

Tyler pressed the acting secretary of state, Richard Rush, to compare the proof text to the original document and certify that it was correct. Rush’s certification was reproduced in facsimile on the Tyler engraving of 1818 and noted the effects of “the hand of time” on the original. This statement that the Declaration was showing wear 35 years after it was penned is the first written report about its condition. In 1819 Philadelphia publisher John Binns published a large ornamented engraving of the text of the Declaration with facsimile signatures below and a statement from Secretary of State John Quincy Adams confirming the accuracy of the text.

While the engravings conveyed the written words of the Declaration and incorporated exact copies of the signatures, they lacked the ability to represent the full presence of the document. So Adams, beset by competing copyists, decided the State Department should commission a full-size facsimile of the Declaration that could be seen in all the states.

Sometime after mid-1820, Adams turned to a young political supporter, William Stone, and commissioned him to engrave a full-size image on a copperplate. The copperplate, which took several years to create and from which engravings on parchment were later commissioned, was dated July 4, 1823.

During Adams’s term as secretary of state, 1817 to 1825, almost anyone could enter the Department of State and ask to see the Declaration. With the creation of this now iconic facsimile, no longer would copyists—or casual visitors—be permitted access to the original at the State Department.

The evidence the copyists left on the Declaration is diminished ink in the areas of text and especially in the signatures. The engravings associated with Tyler, Binns, and Stone all bore facsimile signatures, and Stone’s engraving also had facsimile text.

As photography had not yet been invented, the copyists would have worked directly from the original to capture exact images of the signatures and words. While other techniques could have been used in copy making, using wet paper or fabric to press against the water-soluble ink was a fast method that produced the mirror image that was needed for an engraving plate. It seems likely that the signatures were subjected to the wet-copy method more than once, probably by all three copy efforts.

Adams had envisioned that creating a full-size facsimile of the Declaration would protect the original parchment from excess handling and limit the number of visitors who came to his office to see the actual document. While the copies did help to limit handling, other risks were on the horizon.

An Era of Exhibition

Takes Its Toll

Beginning in 1841, the Declaration was exhibited in the new Patent Office Building, which had the first public exhibition hall in Washington. The building, deemed to be “fire proof,” had a large Hall of Models on the top floor, where the Declaration was exhibited in the same frame with George Washington’s commission as commander in chief.The hall had a skylight and large south-facing windows. An exhibition catalog from 1859 notes the Declaration’s location on the wall between two windows shaded by the massive south facing pediment. While the Declaration hung on a wall with some shade from the south, the cumulative exposure to light in the space—especially for the 35 years of exhibition—was extreme.

During the 19th century, the Declaration was on exhibit for more than half a century: 35 years in the Hall of Models, one at Independence Hall, and 17 at the State Department library under uncontrolled environmental conditions. In addition, the damaging effects of excess light on ink were not widely understood. One physical change to the Declaration as a result of long exhibition was a change in the ink color to a warm, pale brown.

In 1876 President Ulysses S. Grant approved sending the Declaration to Philadelphia for display in the United States Centennial Exhibition, which was attended by almost 10 million visitors. The Stone engraving had made the overall design of the Declaration familiar to the public but not its actual condition. Viewers who saw the original parchment in Philadelphia were struck by its damaged appearance. Published accounts commented on the faded appearance of the ink. Some specifically noted that most of the signatures were “effaced” or “illegible.”

A desire to take action led to a Joint Resolution of Congress (19 Stat. 216) passed in August 1876 while the document was still on view in Philadelphia. The resolution called for a joint commission of the heads of the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress, and the Interior Department to look into restoring the ink text and signatures on the document.

The State Department as Custodian:

Conservative and Cautious

At end of the centennial exhibition, despite growing concern over the condition of the Declaration, it was returned to the new fireproof State, War, and Navy Building and put on display in the State Department library.

The joint commission asked the National Academy of Sciences in 1880 to form a committee to determine whether restoring the ink was appropriate. The NAS committee’s January 1881 report argued against any attempt to restore the ink by chemical means but instead recommended that the Declaration be stored in the dark and that no future press copies be made. This report did not result in immediate changes.

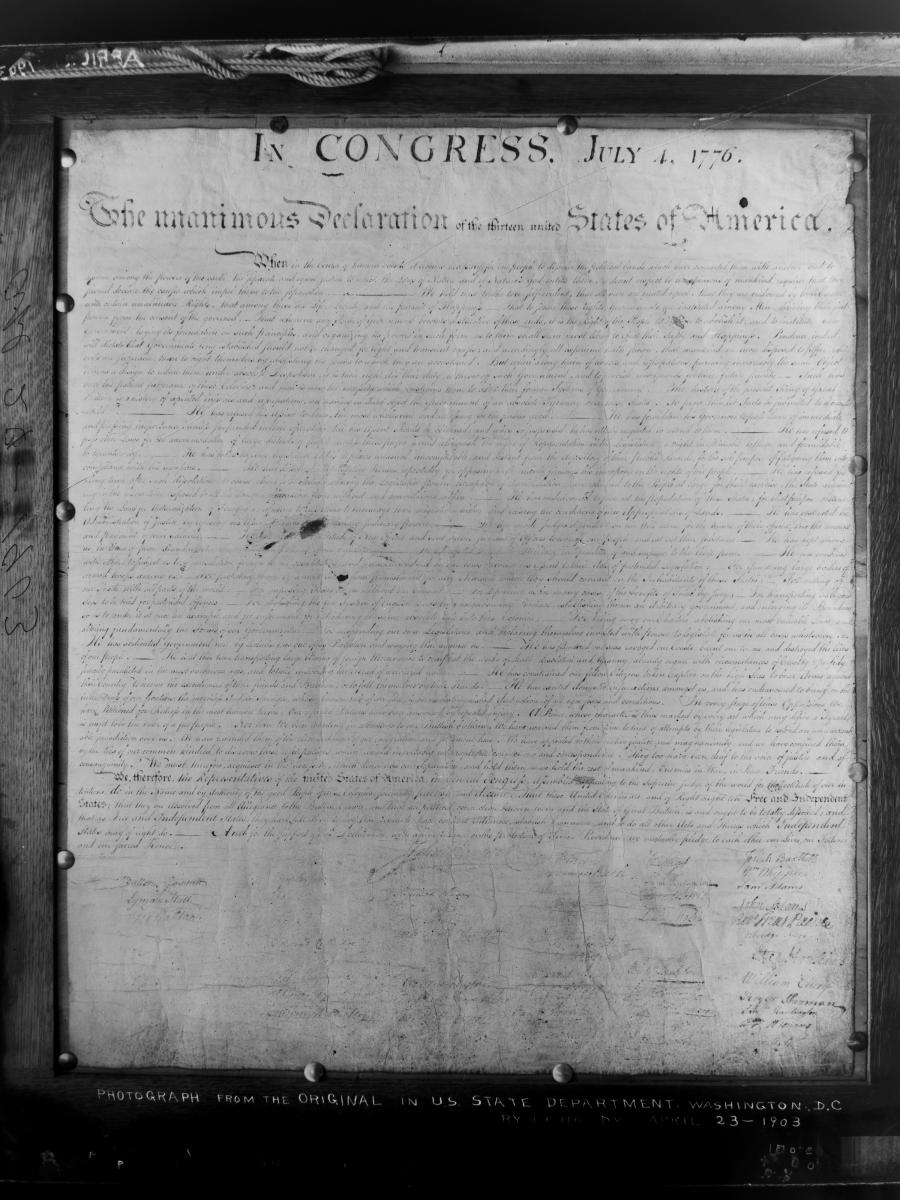

In 1883 the first known photograph of the Declaration was taken by Washington photographer Levin C. Handy. Despite extensive searching, however, it has not been located. A collotype photograph of the Declaration made by Washington printer Albert G. Gedney that same year survives in rare copies. A copy of the collotype was briefly loaned to the National Archives by one of Gedney’s descendants and photographed in the 1980s.

In 1894 the State Department announced that the Declaration would be replaced in the display case with a facsimile, and the original was to be stored “wrapped and placed flat in a steel case.” The Declaration was still accessed occasionally. It was photographed and printed in a special commemorative 1898 issue of the Ladies’ Home Journal. The picture’s caption described the document as still in legible condition though the signatures were “blurred” from excess light exposure.

State Department concerns about the Declaration’s condition persisted. Secretary of State John Hay asked the National Academy of Sciences in 1903 for recommendations on preserving the Declaration. A new, smaller NAS committee was formed with chemistry professor Charles F. Chandler, who had served on the 1880 committee, as chairman.

The Chandler panel quickly prepared the first thorough report of the condition of the document: evidence of rolling and of folding, diminished ink from press copying, fading from excess light exposure, but no evidence of mold or active deterioration. The committee strongly opposed applying any chemicals or restoring the ink or applying a coating on the parchment.

Committee members noted that the 1883 photograph had helped them evaluate the document when they examined it with the Chief of the Bureau of Rolls and Library at the State Department. They made a significant recommendation that the Declaration be photographed and again at intervals in the future. They advised continuing the practice of storing the Declaration in the dark under as dry conditions as possible and never exhibiting it. Significantly, the committee did not mention evidence of tide lines or water damage.

Secretary Hay acted immediately on the recommendations. He had the Declaration photographed again by L. C. Handy in April 1903. The large Imperial format glass plate negatives captured a remarkably detailed image of the document that allows careful comparison between the condition of the Declaration as it was in 1903 with how it appears today. Handy’s photograph makes clear that a number of changes and alterations have occurred since 1903.

In April 1920, the secretary of state appointed a new committee to advise on care and preservation of the “original Declaration of Independence, Constitution . . . Treaties, Proclamations and Laws . . . deposited with the Department of State.” The committee reported in early May that the Declaration and Constitution were in thin, steel-walled safes that were not fireproof or secure and that smoking was allowed in the library.

Examining the Declaration unframed, they concluded that the damage was the result of careless handling in the past. They stated, “We see no reason why the original document should not be exhibited if . . . exposed only to diffused light.” Further, they recommended that the Department of State transfer the original papers of the Continental Congress—including the Declaration of Independence—to the Library of Congress. This was done the following year.

Another Journey—

To the Library of Congress

In 1921, the secretary of state proposed to the new President, Warren G. Harding, that the original Declaration and Constitution be transferred to the Library of Congress, which had “experts skilled in archival preservation, in a building of modern fireproof construction, where they can safely be exhibited to the many visitors who now desire to see them.”

Harding issued an executive order to this effect in September. When Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam received the order, he immediately went to the secretary of state. The documents in large oak frames were carried to the library’s mail truck and cushioned on a pile of leather mail bags for the drive to the library. The precious documents were placed in the Librarian’s office safe.

A new marble shrine, dedicated in February 1924, was built in the Great Hall of the Jefferson Building against an exterior wall between large west windows that admitted abundant light into the space. Putnam himself installed the Declaration, which had been secured in a green velvet-covered window mat, into the vertical shrine frame, with the leaves of the Constitution displayed below. The Declaration and Constitution remained on display until 1952 (with some interruptions), behind double panes of glass with yellow gelatin filters intended to block harmful light.

Surviving Insects,

Humidity, and War

By the early 1940s, however, the shrine display had several problems. Protein-eating beetles were found in the lower case, where the Constitution was displayed, while both the Constitution and the Declaration experienced uncontrolled humidity, common in the days before air conditioning. When humidity was high, adhesive holding the edges of the Declaration in the display mat softened. Then when humidity dropped, the parchment contracted and strong tension between the parchment, adhesive, and the mat caused the parchment to tear. Guards reported tears at the top right corner of the document; these tears grew longer over time.

If that were not enough to worry about, increasing concern about the risk posed by World War II led to secret plans in April 1941 to evacuate the library’s top treasure documents to the Bullion Depository at Fort Knox, Kentucky. These plans were put into action after the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor.

Many statements were made over the years regarding the condition of the Declaration, but it was not until November 1940 that a conservator—George Stout of Harvard’s Fogg Museum—examined it at the Library of Congress and recorded detailed observations on its condition.

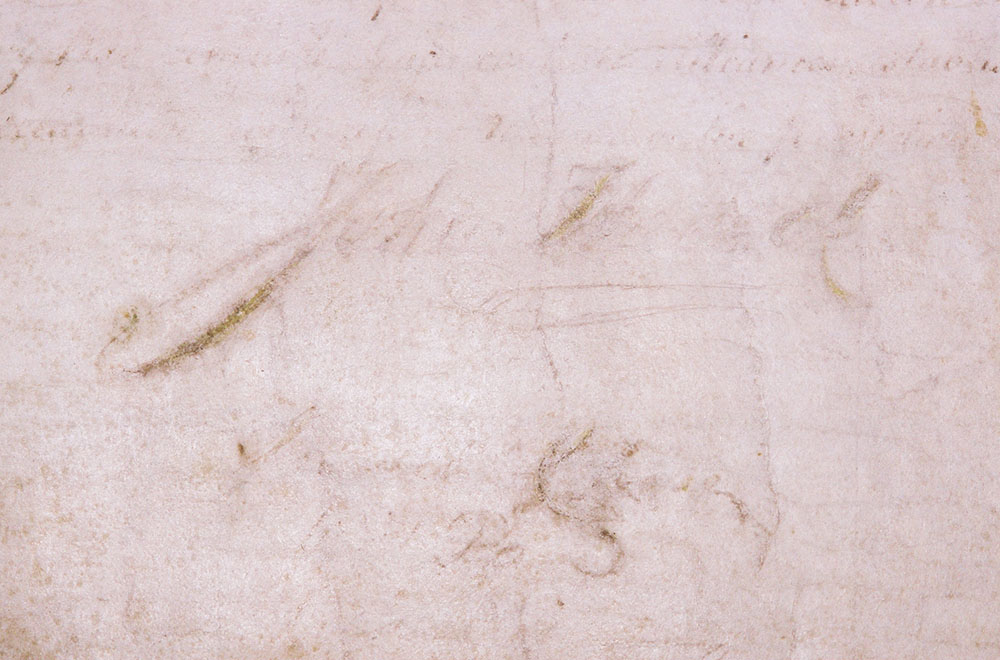

Stout noted the presence of holes and tears, the largest ones in the upper right corner caused by the mounting technique, as well as evidence of previous mends with paper and tape. Regarding the state of the parchment, Stout noted that it seems “firm and strong,” and that the “ink of the writing has become dim, either from fading or chalking.” His report also includes the first known recorded mention of “a vague imprint of a hand” in the lower left of the parchment.

In May 1942, Stout and Fogg Museum paper and parchment conservator Evelyn Ehrlich examined and treated the Declaration at Fort Knox. Their report includes the first known written reference to “large water stains.” When looking at the Declaration today, these stains and tide lines, created by water that dissolved and redeposited ink, are a dominant feature of the document and represent some of the most significant damage.

Stout and Ehrlich’s treatment stabilized the document: old mends and adhesive (paste, glue, and cellophane pressure-sensitive tape) were removed, and tears and holes were repaired on the reverse. They filled the holes with new parchment and made mends with mulberry fiber paper secured with rice paste. Stout and Ehrlich noted the presence of colored media on some signatures, including Hancock’s.

The most noticeable changes following their treatment were mending and securing the torn upper right corner and filling nearby holes in the skin, which helped to both physically and visually integrate the document and make it less vulnerable to future tearing.

A New Kind of Display

And a Final Trip

Responding to the problems of insects in the display case and fluctuating relative humidity, the Library of Congress approached the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) about designing sealed encasements to protect the Declaration and Constitution.

The resulting encasements were forward-thinking and state-of-the-art for the 1950s. They incorporated a free-floating piece of glass resting on the parchment to keep it flat, with an atmosphere of humidified helium to inhibit insects and deterioration. In hindsight, the weight of the glass resting directly on the document probably compressed the tight raised ridges on the parchment.

Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt had stated their intent to house the Declaration and Constitution at the National Archives, and the National Archives Building was built in the 1930s with a special shrine in the Rotunda to exhibit our founding documents. Not until December 1952—after years of discussion and negotiation—were the documents transferred from the Library of Congress for permanent display, along with the Bill of Rights, at the National Archives.

For 50 years, the NBS encasements admirably fulfilled the dual goals of ensuring preservation and providing access. However, with growing knowledge of display techniques and materials science, including concerns about the deterioration of the glass resting directly on the parchment, by the early 2000s it was time for a new approach.

A New Encasement

For a New Century

The opportunity to design and fabricate new encasements that reflected current conservation practice arose in the 1990s, when plans were made to renovate the National Archives Building. The Declaration and other Charters were taken off display in 2001, but National Archives staff, working with colleagues from the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST, successor to NBS) and other experts had already begun designing new encasements.

In 2002, the authors of this article opened the NBS encasement and removed the Declaration, exposing it to air for the first time in decades. After a thorough examination, our team recorded its condition in written notes and reports and via extensive photography. We used this condition assessment as the basis for developing a treatment plan to stabilize the Declaration for a new millennium.

The examination revealed that the Declaration bore physical witness to many years of being handled, rolled, folded, exposed to light, subjected to copy techniques, and mounted for exhibition. Over the decades, ink had sunk into the parchment, flaked off during handling and rolling the document, and been removed during the wet-transfer copy processes used to create facsimiles.

As a result, little original ink remains. The damage to and loss of ink led someone in the past to enhance some signatures, most notably John Hancock’s bold distinct handwriting.

The mends and fills performed in 1942 were still secure, which led to a 2002 decision to accept that work and to leave it in place. One large edge loss below the top right corner was filled with Japanese paper to create a more stable edge. We observed a series of previously undocumented small Y-shaped punctures near the edges, which were presumably made to secure the parchment into a mount early in its history. The parchment surface was gently cleaned only in bare margins, but old grime remained.

No attempt was made to reduce the handprint, which was quite engrained in the parchment and is now part of the Declaration’s history even if its origin is unknown. The parchment was already relatively flat, and the deteriorated condition of the skin supported the decision to passively flatten it under light weight without introducing moisture or humidity.

We built on the 1942 treatment but used a light touch to provide further stability of edge tears and losses without significantly altering the appearance of the document.

Keeping Parchment

Flat: A Challenge

Because parchment responds to changes in humidity by expanding, contracting, and curling, it is difficult to keep flat in an exhibition case or a frame.

From its years of display at the Patent Office, the Declaration retains small Y-shaped punctures along the edges. These apparently were made to lace string mounts to hold the edges flat and in position. The holes are visible along the bottom and right where the parchment edges are heavily soiled and untrimmed.

The Declaration must have been in a new frame when it traveled to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, as it was no longer with Washington’s commission. On its return to the State Department library, it was exhibited vertically, probably held by snug compression against the case glass, until 1894. Then the Declaration and the Constitution were pressed between heavy panes of glass to hold them relatively flat in oak frames for storage. Later, at the Library of Congress, the Declaration was attached to its mount with glue applied on the reverse around all four edges.

Various methods were employed over the years to keep the parchment flat for display, and each had some impact on the condition of the document. The weight of heavy glass compressed and flattened existing folds and crimps. Lacing string mounts around the edges of the skin kept the parchment taut but left puncture holes. Adhesive applied around the edges of the document resulted in tears in the parchment as it contracted and broke free from its mount.

In contrast, the current method of mounting the Declaration departed from the tradition of attempting to control this lively material and used a nonadhesive gentle restraint: polyester film tabs around the edges apply light pressure to secure the parchment to its platform. This mounting technique, along with controlled relative humidity, is designed to minimize physical movement of the parchment and to keep it flat, yet to yield should the parchment contract.

Words Led to Facsimiles . . .

And, Then . . . to Photographs

Photography is the most commonly used tool today to record and convey information about the condition of an object. Before conservators treat significant documents or paintings, they take a series of photographs to document condition.

Photography, however, did not exist for the first 63 years of the Declaration's history. People therefore used words to describe the document’s condition. Richard Rush in 1818 stated that the document showed the effects of “the hand of time.” What exactly did he mean? Without more description, it’s hard to tell. What is clear is that the concern over the physical state of the document led to the creation of facsimiles, both to protect the original and to share the content of the document across the nation.

By closely examining early photographs of the Declaration, one can track its condition over time.

Photography as Evidence;

The Mystery of the Handprint

Today the document looks different from how it appeared in the detailed 1903 photograph; some changes are subtle, others more striking. The 1903 photograph, as well as the 1883 Gedney collotype and 1898 Ladies Home Journal photograph, show a document, despite some diminished ink, with a text that is completely legible and free of water stains and tide lines. The signatures are more diminished, but all signatures seen on the Stone engraving are present in correctly aligned columns.

Today looking closely at the lower left corner of the Declaration, you will see the distinct image of a handprint—first noted in 1940—that is not present in the 1903 photograph. The mystery of the handprint—how it occurred, when, and by whom—has not yet been solved.

One also notices the tide lines and a blurring and overall loss of legibility of many words in the text. A further substantial alteration is in the signature section. Some signatures, such as John Hancock’s, were enhanced while others were rewritten in efforts to make them more visible. It is significant that the handprint, the tide lines, the blurring and illegible ink text, and the changes to the signatures are not seen in the 1903 photograph. The early photographs prove that the defining damage that made the Declaration what it is today was not the result of 19th-century copying or excessive exhibition, but occurred in the 20th century.

In 1922 the Library of Congress had Handy photograph the Declaration to document its condition on receipt. But despite many efforts, beginning with those of Verner Clapp of the Library of Congress in the 1940s, no one has located Handy’s 1922 work. This photograph would be pivotal to tracking changes to the Declaration and when they occurred.

Clapp, however, was successful in his efforts in the 1940s to reinstate a program of regular photography of the Declaration. Photographs made at the Library of Congress in 1940, 1941, and again in 1942, document the first modern conservation treatment of the Declaration.

Between 1903, when the Department of State commissioned photographs for the National Academy of Sciences committee, and 1940, someone with access to the document took drastic steps that altered the document significantly. To date, no contemporary written documentation has been found that describes what can only be described as the defacement—even if unintentional—of the Declaration.

America’s Charter

And the Hand of Time

So what does this thread of words, copies, photographs, and—most importantly—the Declaration itself tell us as we look at it today?

Certainly that the Declaration was much loved by the American people. It was moved to keep it safe from wars. It was copied and then exhibited to share it with the public. But the techniques used to keep it safe and accessible sometimes took their toll on the parchment and the ink.

Mysteries persist.

Many have attributed the damaged condition of the Declaration to excess light exposure during long exhibit in the old Patent Office (now the National Portrait Gallery). But light fading would result in an even fading overall, and the ink instead is unevenly diminished, much more in some central places than along the edges.

L. C. Handy’s 1903 photograph shows neither the handprint nor the tide lines that others have attributed to the wet-transfer copy process. But Stout and Ehrlich’s 1942 examination notes mention these features, which are also clearly seen in photographs taken in 1940 and then in 1942 during the treatment at Fort Knox.

Something happened to the Declaration between 1903 and 1940 that was not documented or has not yet been uncovered. Future research may answer these questions. It is like a puzzle for which some pieces (or photographs) are missing and may emerge.

In the meantime, the Declaration of Independence resides in the Rotunda of the National Archives, preserved and safe for future generations. The words and the intent persist, even if the physical object shows the effects of “the hand of time.”

Catherine Nicholson was Deputy Chief of Conservation at the National Archives, and Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler was Chief of Conservation. Both now retired, they served as the team of conservators who examined and treated the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights, and also served on the design team for the current encasements.

To Learn More About

- The 2003 re-encasement of the Declarations, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, go to www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2003/fall/charters-new-era.html.

- The long journey the Charters of Freedom took to get to the Rotunda in the National Archives Building, go to www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/winter/travels-charters.html.

- The stylistic artistry of the Declaration of Independence, go to www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration_style.html.