Faith on the Firing Line

Army Chaplains in the Civil War

Spring 2016, Vol. 48, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By John P. Deeben

On the late afternoon of July 2, 1863, the regiments of the Second Brigade, First Division in the Second Corps of the Army of the Potomac—the famed Irish Brigade—assembled on Cemetery Ridge to confront the devastating Confederate assaults on the second day of the battle of Gettysburg.

As the brigade prepared to advance, a lone figure climbed upon a large boulder to address the troops.

In one of the more famous moments of the battle—a scene so well known that it was later recreated by Hollywood in the 1993 film Gettysburg—one of the brigade chaplains, Father William Corby, performed an impromptu rite of general absolution (the collective forgiveness of sins without prior individual confession) for the assemblage of predominantly IrishCatholic soldiers. Fortified by the blessing, the Irish Brigade moved forward into the killing zone known as the Wheatfield, adding one more chapter to its distinguished career.

Father Corby’s actions at Gettysburg highlight the important religious service that military chaplains provided to the common soldier during the Civil War. Clergymen of all faiths and denominations served with distinction in both Union and Confederate armies, overseeing the moral and spiritual well-being of the troops. Such care proved essential to soldiers who faced the constant uncertainty of violence and death on the battlefield and reinforced the religious underpinnings of a society in which faith played a much more immediate role in daily life—the Civil War, after all, occurred in the midst of one of the largest evangelical revival movements (the Third Great Awakening) of the 19th century.1

The military service of Army chaplains, therefore, deserves considerable attention. The National Archives and Records Administration holds various sources that document the service of both Union and Confederate chaplains during the Civil War.

Army Chaplains Serve as Field and Staff Officers

Most military clergy during the Civil War served as regimental chaplains and accompanied the armies on campaign, although many were assigned to post and field hospitals as well. Regimental chaplains usually served as part of the headquarters or field and staff officers rather than being attached to specific companies. In the National Archives, chaplain service is documented in the same way as volunteer soldiers, with compiled military service records (CMSRs) located in the Records of the Adjutant General's Office (AGO), Record Group (RG) 94.

The War Department began compiling carded service records for Union soldiers in the 1890s to improve the verification process for pension applications. War Department clerks abstracted service data for each soldier from a variety of available sources, including muster rolls, payrolls, morning reports, and other regimental records, onto a series of cards, creating a succinct personal history that usually identified the volunteer's rank, dates of enlistment and discharge, presence or absence at monthly roll calls, and any other noteworthy activities.2

Carded service records for Union chaplains are filed in the series "Carded Records, Volunteer Organizations: Civil War" (entry 519) in RG 94. Arranged by state, then by arm of service, then numerically by unit and alphabetically by name, most of the records are textual; only service records for border states, western states and territories, and southern states that raised Union regiments have been microfilmed and now digitized on www.Fold3.com.3 Separate indexes exist for the records of each state.

In addition to Father Corby, whose service record is filed with the 88th New York Infantry, the series includes information about Rev. John Hobart, whose lengthy career as chaplain of the Eighth Wisconsin Infantry from December 16, 1862, to September 5, 1865, was briefly interrupted by a dismissal for inefficiency from July 15 to October 10, 1864. Interestingly, Hobart's spouse, Elvira Gibson Hobart, also served unofficially as chaplain of the First Wisconsin Heavy Artillery; regrettably, no service record exists because Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton refused to muster her formally into service despite an appointment by Wisconsin governor James T. Lewis.4

Service records for Confederate chaplains are located in the series "Carded Records Showing Military Service, 1861–65 and Later" (entry 193) in the War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109. The War Department created carded service records for Confederate soldiers between 1903 and 1927, using captured records and other personnel documents from private collections and Southern state governments.

Reflecting the incomplete nature of surviving Confederate records, the series includes the rather brief record of Father Emerson [Emmeran] M. Bliemel, chaplain of the 10th Tennessee Infantry, who was reportedly the only Catholic priest—and the first American chaplain in general—killed in action during the war. Bliemel's record includes cards drawn from two regimental rosters and a field and staff muster roll, all of which show his appointment as regimental chaplain on February 10, 1864. Inexplicably, the file makes no mention of Bliemel's death at the battle of Jonesborough, Georgia, on August 31, 1864. He was decapitated by a ricocheting cannonball while administering last rites to his mortally wounded regimental commander, Col. William Grace.5

Additional service records for Union chaplains in nonregimental staff positions are contained in the series "Carded Records Relating to Civil War Staff Officers" (entry 518) in RG 94. Arranged alphabetically by name, the files are similar to the enlisted service records. They identify staff officers by name and rank and provide information gleaned from departmental and hospital rosters and muster rolls.

The file for Rev. Paul Wald shows that he was appointed hospital chaplain at the U.S.A. General Hospital in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on May 8, 1864, and appeared on the hospital rolls through August 1864. He then transferred to the U.S.A. General Hospital at Natchez, Mississippi, on September 4, 1864, and remained there until March 1865. During the same period he also appeared present for duty on the monthly returns for the Post and Defenses of Natchez, Mississippi, as well as the rolls for the District of Natchez, Department of Mississippi. The final card in the file indicated that Wald was dismissed from service by a general court-martial on April 8, 1865.6

Carded records for Confederate chaplains appointed to brigade or division-level staffs are published in National Archives Microfilm Publication M331, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Generals and Staff Officers, and Non-regimental Enlisted Men. Arranged with other specially appointed officers such as aides-de-camp, military judges, agents, and drillmasters, these chaplain records include card abstracts of information found in original appointment ledgers, lists of staff officers, returns, muster rolls, and inspection reports. They also include references to special orders and other original or published records, and original papers relating solely to the individual soldier. The records generally do not include information about earlier or later service with specific regiments or other military units, although they may contain cross references to available regimental service.7

The records have been digitized on Fold3 and are indexed by National Archives Microfilm Publication M818, Index to Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations Raised Directly by the Confederate Government and of Confederate General and Staff Officers and Non-regimental Enlisted Men.

The War Department Keeps Files and Registers on Chaplains

In 1863 the War Department began keeping records about Union officers that effectively served as individual personnel files (similar records do not exist for Confederate officers). The files were maintained by the Commission Branch—later renamed the Appointment, Commission, and Personal (ACP) Branch—in the AGO and consisted of correspondence, orders, and endorsements pertaining to Regular Army officers, volunteer staff officers appointed by the President, and other personnel, including hospital stewards, ordnance sergeants, and post and regimental sutlers. The files typically contained information about various aspects of an officer's career, including appointments, transfers, assignments or duties, promotions, disciplinary actions, and discharges or resignations.

Arranged by year and then according to a specific file designation that included the initial letter of the officer's surname, an assigned file number, and the letters "CB" for Commission Branch, the files are reproduced in National Archives Microfilm Publication M1064, Letters Received by the Commission Branch of the Adjutant General's Office, 1863–1870 and are also digitized on Fold3.8

The Commission Branch files often include records about chaplains who served as regimental or military post staff officers. Typical is the file (A184-CB-1863) of Mordecai J. W. Ambrose, a Methodist chaplain of the Seventh Kentucky Cavalry and 47th Kentucky Infantry. Ambrose's CB file documented his appointment as a hospital chaplain at Nashville, Tennessee, in 1863, and included several letters of recommendation addressed to President Abraham Lincoln. Ambrose duly received a commission on September 28, 1863, but the U.S. Senate later rejected the appointment on account of some unresolved health issues that appeared to disqualify Ambrose for service (he had resigned from the Seventh Kentucky for physical disability resulting from an attack of fever). Although "Deeply mortified and chagrined" and "thrown into a violent fever" because of the unexpected turn of events, Ambrose obtained the necessary medical clearances to verify his recovered health and reapplied several more times, including a petition to President Andrew Johnson for a chaplaincy in the postwar military. The record does not indicate whether Ambrose ultimately regained his appointment.9

Sometimes the Commission Branch files contain useful biographical information. The file for Rev. Mark Lindsay Chevers, who served as the post chaplain at Fort Monroe, Virginia, during the Civil War, contained letters showing he was born in New York City on May 12, 1794, commenced his ministerial duties at Fort Monroe on December 1, 1838, and eventually died at his post on September 13, 1875. Similarly, after the War Department appropriated Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown, District of Columbia, for a military hospital in 1862, the parish rector Rev. Joseph Aschwanden applied for and received a commission to serve as the hospital chaplain.

In his letter accepting his commission on May 4, 1863, Aschwanden noted that he was born in the Republic of Switzerland on December 23, 1813, and immigrated to the United States in 1848. Settling in Georgetown, he filed a petition to become a U.S. citizen on July 3, 1852, and received his naturalization certificate on December 8, 1858.10

The War Department's registers of appointments also includes chaplains. The series "Registers of Applications for Military and Civilian Appointments ('Applications for Office'), 1847–92" (entry 246) in the Records of the Office of the Secretary of War, Record Group 107, contains various listings of candidates for Volunteer and Regular Army commissions during the Civil War. Besides chaplain, applicants vied for such positions as quartermaster, paymaster, surgeon, ordnance or recruiting sergeant, or an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Other civilian positions included sutler, civil engineer, military storekeeper, clerk, purchasing agent, clothing inspector, watchman, detective, and such artisan trades as blacksmith, carpenter, machinist, and patternmaker. The registers typically identified the applicant's name, place or state of residence, the position sought, names of persons submitting recommendation, and whether the individual received the commission.11 A related "Register of General and Staff Officers of Volunteers, 1861–65" (RG 94, entry UD 158) also contains entries for hospital chaplains.

The related application files are organized in the series "Applications for Civilian Appointments and Regular Army Commissions, 1847–87" (entry 259) in RG 107. Arranged alphabetically, the files often include letters of recommendation and appointment, oaths of allegiance, and press copies of replies to correspondence.

In addition to civilian and military appointments, some of the files also pertain to War Department employees requesting promotions, transfers, or retention in office. Many of the military applications from 1862 were forwarded to the Adjutant General's Office and are reproduced in National Archives Microfilm Publication M619, Letters Received by the Office of the Adjutant General (Main Series), 1861–1870 (a corresponding index is also available in microfilm publication M725, Indexes to Letters Received by the Office of the Adjutant General (Main Series), 1846, 1861–1889).

Beginning in 1863 all applications for commissions in the Regular Army were forwarded to the AGO's Commission Branch.12

A typical application file is that of Rev. G. W. Bridge, a Methodist Episcopal pastor from Cooperstown, New York. On October 7, 1862, Bridge wrote to Judge Advocate Lafayette C. Turner in Washington, D.C., asking for a chaplaincy at a military post because he was "physically disqualified for a place in the ranks of our Army, or for the Chaplaincy of a Regiment." Bridge's application letter included a recommendation from residents of Cooperstown, who urged Turner to support the appointment because Bridge "has done good service in aiding Volunteering & sustaining the Administration by his many strong appeals in Town and School District meetings." Turner duly forwarded the application to Secretary of War Stanton on October 17 and included his own endorsement, noting that Bridge "is an earnest, outspoken loyal man . . . and would be of great use in a Hospital or at a Military Post. I heartily endorse his application."13

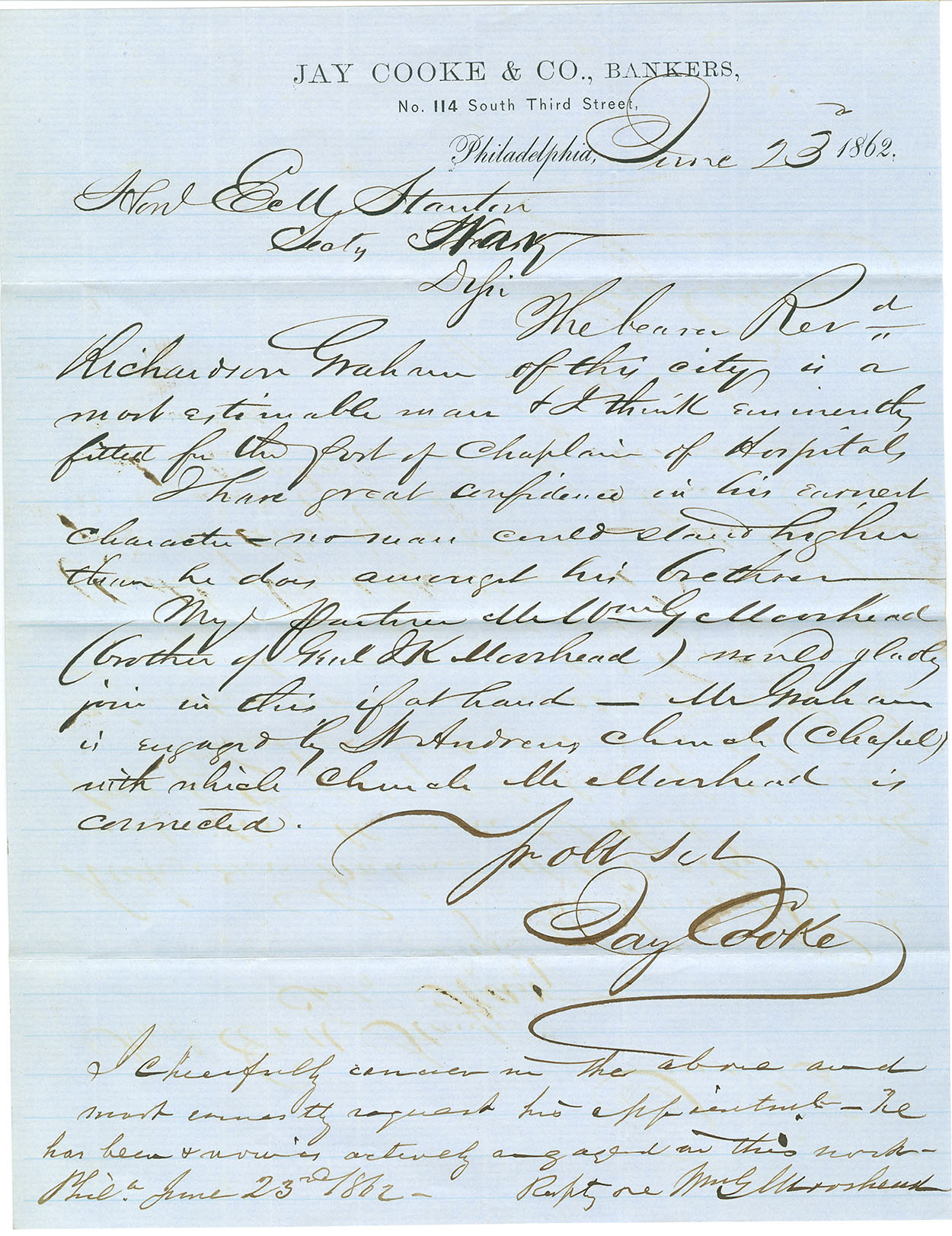

A few fortunate applicants were able to enlist notable patrons for assistance. When Rev. Richardson Graham of St. Andrews Episcopal Church in Philadelphia applied for a hospital chaplaincy in 1862, he solicited the sponsorship of parishioner William G. Moorhead, who was the brother of Congressman James K. Moorhead of Pennsylvania. Noting that Graham was "a friend of mine & a most worthy good man," Moorhead urged the congressman "to send the enclosed [application] to Mr. Stanton with your wish for his appointment." To help clinch the deal, Moorhead's business partner, noted Philadelphia financier Jay Cooke, also provided a glowing recommendation.

Writing directly to the secretary of war, Cooke observed that "Rev. Richardson Graham of this city is a most estimable man & I think eminently fitted for the post of Chaplain of Hospitals. I have great confidence in his earnest character—no man could stand higher than he does amongst his brethren."14

The Confederate War Department compiled registers about chaplain appointments as well. A "Register of Appointments of Chaplains" (RG 109, chapter I, volume 132) in the personnel records of the Adjutant and Inspector General's Office provides a straightforward listing of clergymen approved for the Confederate military. Arranged chronologically by date of appointment, each entry noted the name of the chaplain, state of residence, and the unit or place of assignment or the person to whom they were ordered to report. Most of the chaplains were placed with various regimental organizations, although some reported to brigade and division staffs or other military institutions.

After the war began, Rev. James M. Campbell of Alabama was assigned to serve with Gen. Braxton Bragg on May 7, 1861, while N. Aldrich of South Carolina reported to Fort Moultrie on May 23, 1861, and O. H. Sears of Virginia to the military hospital at Lynchburg on June 12, 1862.15

Chaplains Report Religious Activities

While the service records and officer files document general histories of military service, more detailed information about the religious activities of Army chaplains, especially those assigned to military hospitals, is also available. The War Department required most hospital chaplains to submit monthly reports to the AGO and, beginning in March 1864, to the Surgeon General of the Army.

Located in the series "Reports of Chaplains: Civil War" (entry 679) in RG 94, these reports included certain required information, such as the current duty station of each chaplain, post office address, and the orders under which they were acting, as well as a record of monthly activities in ministering to the spiritual welfare of their patients or other troops stationed at the post. Additional paperwork sometimes included copies of orders pertaining to furloughs or discharges, and notices about chaplains who died while on active duty.16

Most chaplains reported general statements about such duties as the number of weekly religious services, daily visitations to the hospital wards, and other activities of religious instruction. Chaplain L. H. Monroe, who served at the U.S.A. General Hospital in Parkersburg, West Virginia, for example, noted in October 1864 that "I have continued my usual daily visits to the wards, have continued to preach twice on the Sabbath, and kept up my regular Prayer Meetings and Bible Class during the week."17 Other opportunities for spiritual and intellectual enrichment included Sunday schools, choirs, schools for reading and writing, the distribution of Bibles from the American Bible Society and religious tracts from various benevolent societies, and lyceums or public lecture programs.

In addition to his regular duties at the military prison depot at Johnson's Island, Ohio, Chaplain Robert McCune managed a large lending library of over 700 volumes that was "open every day and evening for the convenience of those wishing to take out books." He even boasted circulating over 800 religious papers and 100 Bibles per week.18

Many hospital chaplains also reported monthly information about deaths and funerals as part of their responsibilities for administering last rites. For the most part, the reports usually did not identify the deceased by name, but instead provided general statistical summaries. In his report for December 1864, Chaplain Monroe at Parkersburg duly mentioned that "one death has occurred during the month, the funeral attended."

The following month he recorded a high of nine deaths, including "one white & eight Colored soldiers." On a few occasions, extenuating circumstances prevented Monroe from facilitating his burial duties. In March 1864 he reported the death of two patients at the hospital, but "as the Remains were forwarded to their friends, I could not attend the funerals." In September Monroe likewise reported six deaths but only four funerals, noting "The other two sent home for burial." The following March he also reported one death that occurred while he was absent on leave.19

A few chaplains, finally, went beyond the mere reporting of facts to offer personal assessments of their spiritual influence. Most, of course, believed their work had a positive effect.

At the end of the war, Chaplain G. M. Blodgett, who was assigned to the De Camp General Hospital at David's Island in New York Harbor, observed with enthusiasm that "An elevated moral tone is indicated from the attendance upon religious instruction and the excellent discipline which prevails." He trusted firmly that "not a few have thereby been soothed & comforted, with the consolations of the Gospel in their dying hours."20

Chaplain James H. Brown at the U.S.A. General Hospital in Beaufort, South Carolina, likewise affirmed that he had "good reason to believe that under the influence of Divine Services and social meetings a number [of patients] have greatly improved their Spiritual conditions."21 Chaplain Bernardine F. Wiget also pronounced the moral condition of the Stanton and Douglas General Hospitals in Washington, D.C., to be "excellent."22

Chaplains Held Accountable By Military Courts-Martial

Despite the high moral standing of their profession, some chaplains succumbed to the pressures or temptations of Army life and subsequently found themselves in disciplinary trouble. Chaplains who broke the established rules of military conduct faced the same consequences as enlisted men or officers and were usually subjected to judgment by court-martial. Records of general court-martial proceedings held during the Civil War are located in the series "Court-Martial Case Files, 1809–94" (entry 15A) in the Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), Record Group 153. Typical case files usually included documents describing the organization and personnel of the court; charges and specifications; handwritten transcripts of the trial proceedings, findings, and sentences of the court; witness testimony; documentary evidence or exhibits; and sometimes copies of the published court-martial orders that summarized the results of the trial. The case files are arranged alphabetically by a letter code, then numerically by file number.23

In the final year of the war, Chaplain Paul Wald of the Officer's General Hospital in Natchez, Mississippi, committed a number of infractions that finally landed him before a general court-martial. At the trial held on March 5, 1865, authorities handed four charges against Wald for incidents dating back to October 1864.

The charges were (1) conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline, which related to an incident of public intoxication at a local saloon in Natchez in the company of enlisted men on October 1, as well as threatening a hospital steward in the presence of patients and attendants on November 1, 1864; (2) drunkenness on duty; and (3) conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, which pertained to the November 27 incident as well as a second bout of public intoxication on January 20, 1865. Wald also apparently tried to entice a hospital steward to visit "houses of ill fame" on February 1, 1865. The final charge included breach of arrest, which accused Wald of appearing in public on two occasions after being placed under arrest and confined to quarters by his commanding officer.24

Wald pled not guilty to all of the charges, but the court determined otherwise. In its final ruling, as published in General Court Martial Order 16, Department of Mississippi, on April 8, 1865, the court found Wald guilty on all but the second charge of drunkenness on duty. The court also found Wald innocent of the second specification under Charge 3, which had accused him of appearing at the Officer's General Hospital in a state of intoxication and "behaving in a boisterous and unbecoming manner." As punishment, the court sentenced Wald to be "dismissed from the service of the United States." The dismissal went into effect from the date of the published order, ironically occurring one day before the war virtually ended with the surrender of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House.25

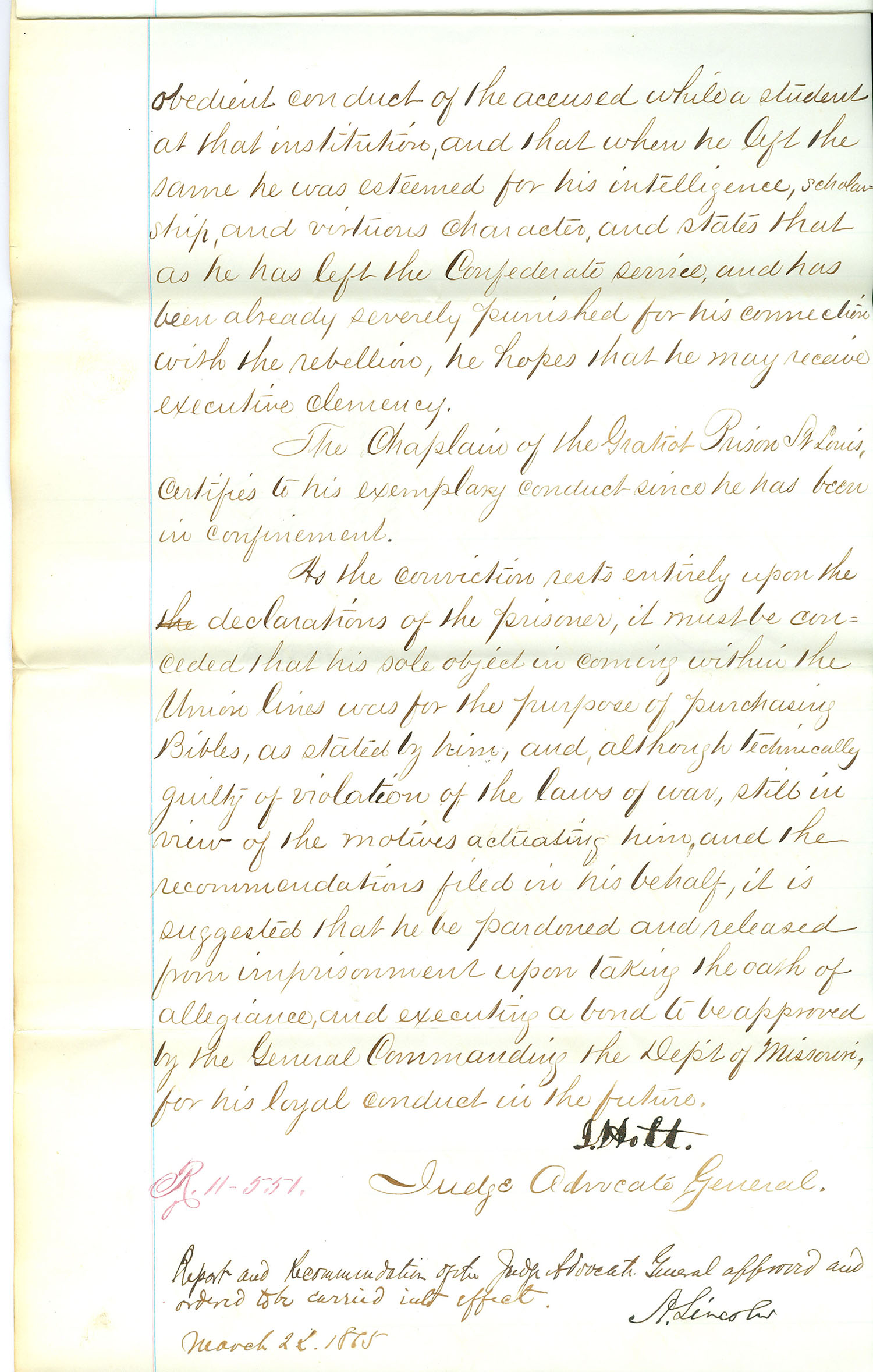

Sometimes, the Union system of military justice ensnared Confederate clergy as well. Such was the case with William M. Patterson, a former chaplain with the 6th Missouri (Confederate) Infantry who was arrested by Union authorities in St. Louis around May 1, 1864. Patterson had allegedly resigned from Confederate service and, believing he was a civilian, traveled through Union lines to Memphis "for the purpose of purchasing Bibles for gratuitous circulation in Arkansas, where he was there engaged in preaching."

After learning that there would be a delay in obtaining the Bibles from New York, he traveled on to St. Louis "to see or hear of his family from whom he had been separated for two years." Patterson was arrested a day after his arrival and brought before a military commission on charges of being a spy and violating the laws of war (crossing into Union territory illegally and failing to immediately report or surrender himself to Federal authorities). For good measure, the commission also accused him of attempting to smuggle contraband of war (boots, shoes, and medicines) across Union lines to aid Rebel forces.26

The military commission convened at St. Louis on December 29, 1864, and after a short trial convicted Patterson of the first charge (violating the laws of war) except for the specification concerning the trafficking of contraband, but found him not guilty of spying. As punishment, the commission sentenced Patterson to confinement for the duration of the war in the Missouri State Penitentiary at Jefferson City. Sometime later, Patterson's father petitioned President Lincoln to pardon William. On March 20, 1865, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt reviewed the case and determined that Patterson had been "induced to join the Rebel army by the earnest soliciting of rebel soldiers to preach for them," but otherwise opposed secession. Holt approved the pardon and recommended that Patterson be released immediately upon taking an oath of allegiance and paying a bond to ensure "his loyal conduct in the future." Lincoln endorsed the decision on March 22, and Patterson was released per General Court Martial Order 156 dated the same day.27

* * *

Whether they served in the field, offering support and comfort to endure the hardships of military life, or cared for the sick and dying in hospitals behind the lines, Army chaplains provided an essential service during the Civil War.

Like Father Corby at Gettysburg, they cared for the spiritual and moral well-being of the common soldiers by conducting regular worship services and prayer meetings, offering religious instruction at Sunday schools and Bible classes, and administering final rites and burials.

They encouraged intellectual nourishment via literacy classes, the distribution of reading material, public lecture programs, and other social interactions. Such care promoted better morale throughout the ranks, allowing the Union and Confederate armies to carry on the fight even as combat became more grueling and sustained during the latter part of the war.

The records created by and about Army chaplains in Blue and Gray reveal in great detail their lasting impact on the conduct of the war.

John P. Deeben is an archivist on the Army team in the Archives I Reference Section of the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. He holds B.A. and M.A. degrees in history from Gettysburg College and the Pennsylvania State University.

Notes

1. John W. Brinsfield et al, eds., Faith in the Fight: Civil War Chaplains (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 2003), p. viii. For other treatments of the religious aspect of the Civil War, see also Steven E. Woodward, While God Is Marching On: The Religious World of Civil War Soldiers (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2001), Mark A. Noll, The Civil War as a Theological Crisis (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), and Sean A. Scott, A Visitation of God: Northern Civilians Interpret the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

2. Lucille H. Pendell and Elizabeth Bethel, Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Adjutant General's Office, Preliminary Inventory No. 17 (Washington: National Archives and Records Service, 1949), p. 102.

3. A complete listing of all microfilmed service records and indexes for both Union and Confederate volunteers is located in National Archives Trust Fund Board, Military Service Records: A Select Catalog of National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1985), pp. 42–74, and 84–162. Researchers at the National Archives Building in Washington, DC, may also consult Reference Report No. 942, Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served during the Civil War The reference report is available in paper format in the Robert M. Warner Research Center.

4. Compiled military service record for Rev. John Hobart, chaplain, Eighth Wisconsin Infantry, Carded Records, Volunteer Organizations: Civil War (Carded Records), Carded Military Service Records, 1784–1903 (Service Records), Records of the Record and Pension Office (Record and Pension Office), Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780's–1917, Record Group 94 (RG 94), National Archives Building, Washington, DC (NAB). Even though Ella Hobart has no CMSR, there is a file (W3370-VS-1864) in Letters Received, Volunteer Service Division, 1861–89 (entry 496), RG 94, that pertains to her failed appointment. For a more detailed discussion Hobart's career, see Brinsfield et al, Faith in the Fight, pp. 36–43.

5. Compiled military service record for Emerson [Emmeran] Bliemel, 10th Tennessee Infantry; Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Tennessee (National Archives Microfilm Publication M268, roll 156); Carded Records Showing Military Service, 1861–65 and Later, Records of the Adjutant General's Office Relating to the Military and Naval Service of Confederates, Records of the United States War Department Relating to Confederates, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109 (RG 109), NAB. For additional details about Bliemel's service and death, see Daniel W. Barefoot, Let Us Die Like Brave Men: Behind the Dying Words of Confederate Warriors (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 2005), pp. 201–205.

6. File for Paul Wald, Chaplain; Carded Records Relating to Civil War Staff Officers, Service Records, Record and Pension Office; RG 94; NAB.

7. Descriptive Pamphlet for M331, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Generals and Staff Officers, and Non-regimental Enlisted Men (1962), located in National Archives microfilm catalog, https://eservices.archives.gov/orderonline/start.swe#SWEApplet1, accessed on October 8, 2015.

8. Pendell and Bethel, Preliminary Inventory 17, p. 63; Maida Loescher et al, Descriptive Pamphlet for M1064, Letters Received by the Commission Branch of the Adjutant General's Office, 1863–1870 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Service, 1980), p. 1.

9. M.J.W. Ambrose to James Speed, March 17, 1865, in Mordecai J. W. Ambrose File (A184-CB-1863); Letters Received by the Commission Branch of the Adjutant General's Office, 1863–1870 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1064, roll 1); Appointment, Commission, and Personal Branch, 1783–1917; Records of Divisions of the Adjutant General's Office; RG 94; NAB.

10. Mark Lindsay Chevers to Maj. Gen. E. D. Townsend, April 29, 1867, and Maj. John C. Tidball to Assistant Adjutant General, September 15, 1875, in Mark Lindsay Chevers File (C184-CB-1868); Joseph Aschwanden to James A. Hardie, May 4, 1863, in Joseph Aschwanden File (A310-CB-1863); both in Letters Received (M1064, rolls 2, 393), Appointment, Commission, and Personal Branch, 1783–1917, Records of Divisions of the Adjutant General's Office; RG 94, NAB.

11. Maida H. Loescher, Inventory of the Records of the Office of the Secretary of War, Inventory 17 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1999), pp. 111–112.

12. Ibid, p. 115.

13. Rev. G. W. Bridge file; Applications for Civilian Appointments and Regular Army Commissions, 1847–87; Records of the Office of the Secretary of War, Record Group 107 (RG 107); NAB.

14. William G. Moorhead to James K. Moorhead, June 23, 1862, and Jay Cooke to Edwin M. Stanton, June 23, 1862; Rev. Richardson Graham file, in ibid.

15. Appointment of Chaplains, 1861–1865 (Chapter I, Volume 132); Records Relating to Military Personnel; Records of the Adjutant and Inspector General's Department, Records of the War Department and the Army, RG 109, NAB.

16. Pendell and Bethel, Preliminary Inventory 17, p. 129.

17. L. H. Monroe, monthly report, October 31, 1864, Reports of Chaplains: Civil War, Administrative Records, 1850–1912, Medical Records, 1814–1919, Record && Pension Office, RG 94, NAB.

18. Robert McCune, monthly reports, December 31, 1864, February 28, 1865, and March 31, 1865, in ibid.

19. Monroe, monthly reports, March 31, 1864, September 30, 1864, December 31, 1864, and March 31, 1865, in ibid.

20. G. M. Blodgett, monthly report, April 30, 1865, in ibid.

21. James H. Brown, monthly report, March 31, 1865; in ibid.

22. Bernardine F. Wiget, monthly report, September 3, 1864; in ibid.

23. George J. Stansfield, "Preliminary Checklist of the Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (War), 1808–1942" (Washington: National Archives and Records Service, 1945), p. 10.

24. General Court Martial Order 16, Department of Mississippi, April 8, 1865, in Chaplain Paul Wald Court-Martial File (OO-556), Court-Martial Case Files, 1809–1894, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), Record Group 153 (RG 153), NAB.

25. Ibid.

26. Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt to Abraham Lincoln, March 20, 1865, in William M. Patterson Court-Martial File (NN-3355); in ibid.

27. Ibid.