Homes on the Range

The Bureau of Indian Affairs Industrial Surveys of the 1920s

Fall 2017, Vol. 49, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

By Cody White

The focus of the photograph accompanying the form was to be the family and its living situation, and to an extent, Superintendent Fred Campbell of the Blackfeet Agency did comply; you can somewhat make out the family’s cabin situated on the far bank of Badger Creek.

But one wonders if the superintendent could not resist capturing the vista, the prairie spreading west into the glacially carved peaks and valleys of the national park created a scant 11 years earlier. That was in 1921, when he personally visited the farm of Joe Ironpipe as part of an industrial survey of Indians and their land allotments on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in northwestern Montana.

The Blackfeet Agency was one of the first to conduct the surveys that would eventually be ordered for every reservation in 1922 by the commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs—surveys that sought to catalog Indian homes, family members, farming activity, health, and debt.

Today these records, found in National Archives Record Group 75, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, are a rich profile of the lives of American Indian families and provide ephemeral information not typically captured in federal records. The photographs and the detailed reports give us a fascinating glimpse of day-to-day life on the reservations.

Joe Ironpipe’s allotment on the Blackfeet Reservation along with extra land he purchased encompassed 420 acres.1 He had 10 horses, 20 head of cattle, 10 acres of wheat, and a garden planned.2 His younger brother, John, helped on the farm, living in a tent near Joe’s cabin and, when pressed by the superintendent, admitted to having no future plans. Joe’s son, Paul, was said to be “very bright” and in “very good physical condition.”3

Joe had logs prepared for a bigger cabin, but one can imagine being a single father was time consuming, for the report also notes he was a widower with three wives and two children lost to tuberculosis.4 In 1921, Paul was all Joe had left.

Bureau of Indian Affairs Allotts Lands to Tribes

With predecessor agencies dating back to nearly the formation of the United States, the Bureau of Indian Affairs was formally created in 1824 by the Department of War to handle relations with the native populations as the country pressed westward.5 A few decades later, the bureau had evolved into its own agency under the purview of the newly created Department of the Interior.

As the primary conduit between the federal government and the various American Indian tribes, the agency unfortunately features a tortured history that tracked the evolution of Indian relations. It is from one such dark chapter, that of the drive for assimilation, that the industrial surveys would eventually emerge.

By the late 1870s, a new policy that had been kicked around for decades had finally taken firm root in the Bureau of Indian Affairs and irrevocably altered the lives of American Indians and what was left of their lands. With tribes already forced onto reservations, the new movement pushed further, contending that if American Indians adapted European-style clothing, the English language, institutional education, and most importantly the concept of land ownership and farming, which was foreign to many of the tribes, they could better assimilate into the United States population at large.6

This viewpoint was a driving force behind 1887’s “Act to Provide for the Allotment of Land in Severalty to Indians on the Various Reservations, and to Extend the Protection of Laws of the United States and Territories over the Indians, and for Other Purposes.” The act directly assaulted the idea of tribal units by instead focusing on American Indians as individuals when it came to the ownership of the vast reservations.7

Known more commonly as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Act, after its author, Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, the 1887 law, along with subsequent laws over the following 20 years, broke up many of the communally held reservations and parceled out allotments to individuals while also opening up the same land to various outside interests.

Indians across the country were now expected to become farmers and to live off the land in ways they had not before. But they had not had any education on how to do so, often on desert-like land inhospitable to any sort of farming or animal husbandry.8 The ultimate failure of the act to introduce industrial independence on many reservations manifested itself in part several decades later, in the driving force behind BIA circular 1774.

Circular 1774: The Commissioner Orders an Industrial Survey

The Blackfeet Indian Reservation, bordered on the west by Glacier National Park and on the north by Canada, experienced several rough winters from 1919 to 1921 that decimated horse and cattle herds. The severity of the winters was exacerbated by the “very low industrial and economic status” of the Blackfeet, leading to nearly two-thirds of the reservation depending on emergency government rations to survive.9

The timing was poor for the BIA, as Charles Burke had just been named the new commissioner of the bureau and Fred Campbell the new superintendent of the Blackfeet Agency. Right out of the gate the pair faced a crisis, not only on the reservation but nationwide, as accounts of Blackfeet starvation were fed to local and national newspapers as well as members of Congress.

In a flurry of letters between Montana and Washington, D.C., Burke attempted to tamp down the controversy while Campbell sought to document the conditions on the ground. On May 14 he wrote to Burke of his plans for “a very carefully detailed report of the situation.”10

Explaining his idea for a survey of the Heart Butte District, where the hardship was most focused, Campbell proceeded to describe a process that bears close resemblance to what would soon grow into a national mandate. It seems that it might have been Campbell who planted the seed of the industrial survey in Burke’s mind, an idea that Burke would begin to suggest to others before the year was out.

Seven months later, in December 1921, Fort Peck Agency Superintendent James Kitch wrote to Washington, D.C., hoping to acquire funds for a communal threshing machine.11 Commissioner Burke replied, suggesting that Kitch conduct a “house to house canvass of the entire reservation, district by district” to see what exactly is being grown and if the machine would be used.12 He went on, suggesting that the results of the survey be combined with photographs and submitted to his office as a report in order to justify the threshing machine purchase. With his response, Burke had given Kitch a head start of sorts to what would become a nationwide request on March 23, 1922.13

Issued by the BIA headquarters, circulars addressed a number of administrative issues regarding education, land, finances, issues, personnel, and new rules and regulations. Circular 1774, addressed to all superintendents, was entitled “Industrial Survey” and called for just that—industrial surveys to be conducted on Indian reservations.

In lamenting the lack of farming progress made on the individual allotments, Burke called for the visits to be conducted along with the agency farmer, matron, and doctor so as to generate as full a picture of life as possible. Photographs were not required, he notes, but “do add much to the reports.”14

The plans for conducting the surveys were to be submitted to Burke no later than 10 days after receipt of the circular, and the text of the circular brooks no arguments for delay, at one point flatly calling out the “stock excuse” of the superintendent who cannot visit with the Indians for a lack of time.15

Superintendents Respond to Circular 1774

If there had been any questions about Burke’s rigid time frame, they were soon answered. The correspondence of the various BIA agencies revealed that superintendents who pressed the deadline or ignored aspects of the circular soon scrambled to explain the delays or gaps with their reports.

Fort Peck Agency Superintendent Kitch had his first report in by May, the “splendid results attending the industrial survey” being congratulated by Burke, but come July the commissioner began pointedly asking where the rest were.16 Despite visiting six farms a day initially, bad rains had slowed his progress—Kitch noted three inches in one hour during one particular trip—and the deluge not only slowed travel but ruined three rolls of film.

Kitch’s issues were not unique. Similar complaints were made of the nearby Flathead Agency’s efforts, an agency that actually took three years to finally submit the complete survey. Superintendent Charles Coe sent in an initial report in July 1923, minus several outlaying farms.17 Both Commissioner Burke and Assistant Commissioner Edgar Merritt continued to hound Coe for the rest of the report, which was finally delivered in October 1925. Coe blamed the delay on failed attempts to reach the final few farmers at home.18

Newly named Consolidated Ute Agency Superintendent E. E. McKean submitted his initial report on June 30, 1922, and added the caveat near the end: “Although this report in many respects will appear too brief for one of such importance, it is hoped that the Office will bear with me.”19 The office would not. Burke fired back in August that the superintendent had failed to grasp the intent of the report and returned it wholesale with a list of desired changes.20

Overall the surveys were slowly being completed. The 1922 BIA annual report stated that 100 plans had been submitted with 30 final reports finished, and they continued to trickle in up through 1925.

So where are these reports and how does someone begin research in them?

Where Are the Surveys? How Do You Access Them?

A researcher looking into whether his or her ancestor was surveyed can start in one of two places. The reports sent to the BIA’s headquarters were consolidated and can be found in Record Group 75, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Entry 762, “Reports of Industrial Surveys, 1922–1929,” held at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

The reports referenced and used in this article are copies that were saved by the local agencies and are held at the National Archives at Denver.

Unfortunately, not all agencies saved copies locally, so it is best to first contact the National Archives field office that holds a particular BIA agency’s records to find out if the reports exist.

Furthermore, the local copies of the surveys were not always identified as such but were given erroneous names as “Family Histories” or “Home Industrial Survey.” Some surveys are not found in their own record series but are instead filed away within larger correspondence series. Again, if a survey is not readily discovered through the National Archives Catalog, it is best to contact the appropriate facility.

Surveys Provide Snapshots of Indian Life, 1921–1925

The genealogical value of these surveys for those with American Indian heritage is immense. For many American Indians living at this time, the bulk of what is available are census forms or similar lists, which only provide the most bare of facts.

The industrial surveys consolidate a variety of data as well as provide facts that lead to further avenues of research within other National Archives holdings, such as BIA student case files, official military personnel files, or even federal inmate case files.

Photographs included in the reports give an added dimension to the descriptions recorded in words and figures. Here are a few of their stories.

In 1922 the young Ute Julius Cloud, who had three years earlier served overseas in the U.S. Army, was just starting out farming his allotment, living in a “fair” appointed two-room house with his family.21 Elsewhere on the Southern Ute Reservation, the Red and Gunn families lived together in a two-room adobe house. The home was in poor condition, but they had a good barn, equipment, and a 20-head herd of sheep.22 Unfortunately, their photograph was taken too quickly; one of the visiting party was captured taking notes in the foreground, and the rest of the shot is out of focus.

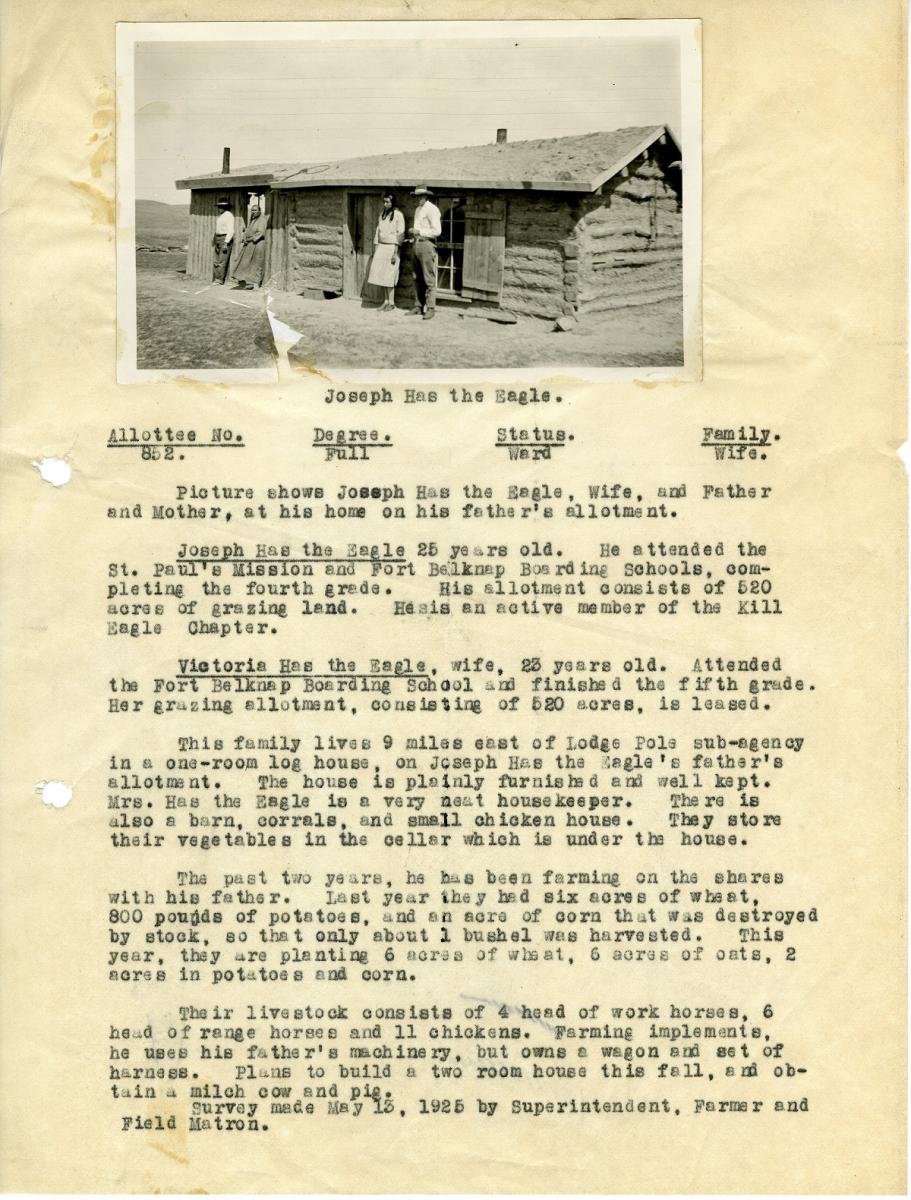

On the Fort Belknap Reservation, home of the Gros Ventre and Assiniboine, Joseph Has the Eagle and wife, Victoria, lived with his parents and raised wheat, corn, and potatoes. Joseph, age 25, attended Fort Belknap Boarding School up through the fourth grade and was planning a new two-room house along with Victoria, age 23, who attended the same school but through the fifth grade.23

Their neighbors were Merlin and Fannie Shield, who had just married the year before in 1924. Merlin, too, was a farmer, having returned to the reservation after a four-year sentence at the Leavenworth Federal Prison for murder. He suffered from chronic appendicitis and had been granted funds for the corrective surgery but was refusing to go through with it.24

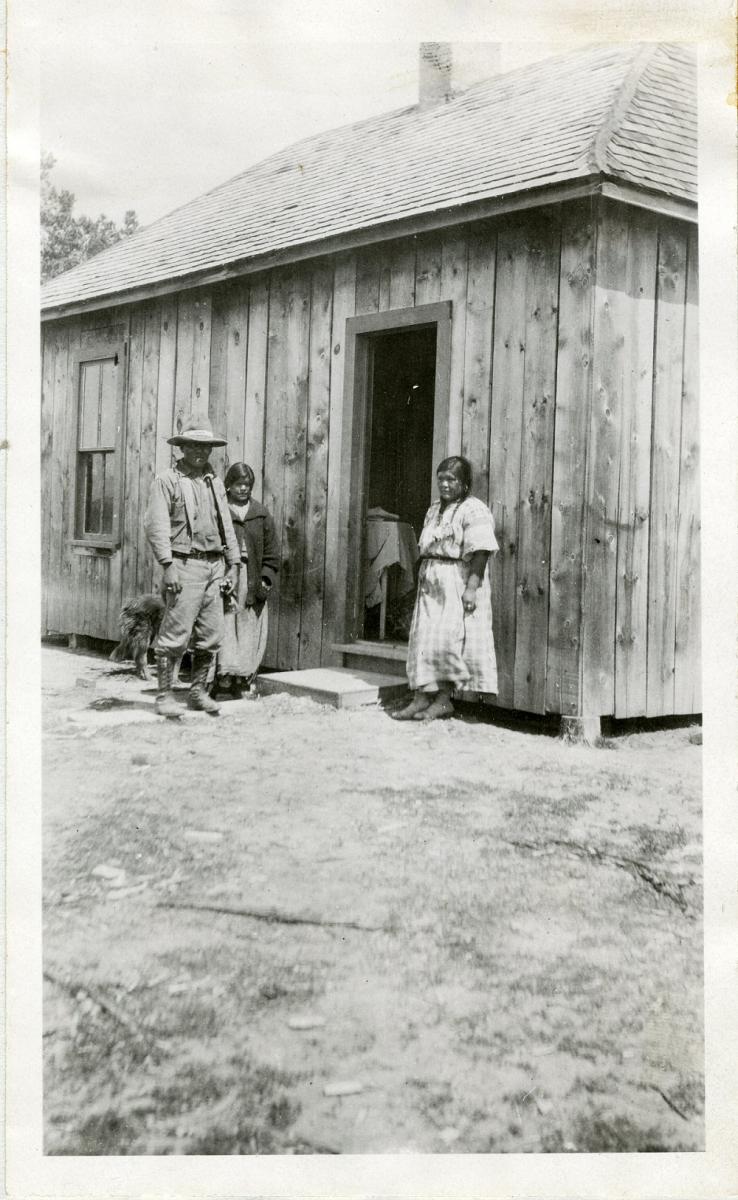

Alexander Calowahcan, a 49-year-old Flathead, lived four miles south of Ronan, Montana, and was married with three children, two of whom regularly attended school. He owned two work horses, nine ponies, and one milk cow and was planning on sowing a combined 55 acres of wheat and oats in 1923.25 The extra men and children in his survey photograph are unidentified.

Elsewhere in Montana, 55-year-old Northern Cheyenne Wesley Meritt’s 65-acre allotment was one mile south of Lame Deer, Montana, where he raised corn, oats, wheat, and potatoes. The family lived in a frame house, had both a barn and implement shed, and was hoping to buy a good milk cow come the winter of 1923.26

Along with Joe Ironpipe, Blackbull, a 52-year-old Blackfeet, also had an allotment on Badger Creek, raising cattle and wheat. Blackbull lived with both his wife and his daughter’s family. Judging from his survey photograph, Blackbull was evidently proud of his little granddaughter, as grandfathers throughout time have been.27

And last, down in Wyoming on the Wind River Indian Reservation, 39-year-old Arapaho Adam Spoonhunter and his wife, Fannie, lived in the one-room log cabin of Fannie’s deceased husband. Despite Spoonhunter’s earlier issues with wheat and oat acreages, the superintendent declared him “one of the best farmers among the Arapahoes.”28

These stories reflect the uniqueness of the industrial surveys as federal records, for they document the actual living conditions of the Indians themselves. Created as a tool to measure the progress made on the various reservations, they have since evolved into a richly detailed genealogical resource, providing invaluable information and perhaps unlocking decades-old clues for both academic researchers and descendants alike.

Cody White is an archivist with the National Archives at Denver. He holds a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities and an M.L.I.S. from the University of California at Los Angeles.

Notes

Locations of National Archives facilities across the nation can be found at www.archives.gov/locations.

1. Joe Ironpipe Industrial Survey, 1921; p. 1; Box 1; Blackfeet Industrial Survey, 1921 (Entry 64); Blackfeet Agency; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group (RG) 75; National Archives at Denver (NAD).

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Bureau of Indian Affairs (accessed May 9, 2017) “History of the BIA,” www.bia.gov/WhoWeAre/BIA/.

6. D. S. Otis, The Dawes Act and the Allotment of Indian Lands (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), pp. 8–9.

7. Ibid., p. 177.

8. Ibid., p. 100.

9.Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1922 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1922), p. 12.

10. Fred C. Campbell to Charles H. Burke, May 14, 1921; p. 1; Box 19; Superintendent’s Subject File, 1908–1929 (Entry 5); Blackfeet Agency; RG 75; NAD.

11. Burke to James B. Kitch, Dec. 16, 1921; p. 1; Box 81; Letters Sent and Received (8NS-75-97-185); Fort Peck Agency; RG 75; NAD.

12. Ibid.

13. Burke to superintendents, Mar. 23, 1922; p. 1; Box 1; Industrial Survey, 1923 (6NS-75-95-006); Winnebago Agency; RG 75; National Archives at Kansas City.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Burke to James B. Kitch, July 20, 1922; p. 1; Box 81; Letters Sent and Received (8NS-75-97-185); Fort Peck Agency; RG 75; NAD.

17. Charles E. Coe to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, July 20, 1923; p. 1; Box 33; Subject Files, 1907–1945 (8NS-75-96-327); Flathead Agency; RG 75; NAD.

18. Charles E. Coe to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Oct. 8, 1925; p. 1; Box 33; Subject Files, 1907–1945 (8NS-75-96-327); Flathead Agency; RG 75; NAD.

19. E. E. McKean “Industrial Report for the Southern Ute,” June 30, 1922; p. 3; Box 162; Decimal Files, 1879–1952 (Entry 44014); Consolidated Ute Agency; RG 75; NAD.

20. Burke to McKean, Aug. 14, 1922; p. 1; Box 162; Decimal Files, 1879–1952 (Entry 44014); Consolidated Ute Agency; RG 75; NAD.

21.Julius Cloud Industrial Survey, 1922; p. 1; Box 162; Decimal Files, 1879–1952 (Entry 44014); Consolidated Ute Agency; RG 75; NAD.

22. Albert Red and Addie Gunn Industrial Survey, 1922; p. 1; Box 162; Decimal Files, 1879–1952 (Entry 44014); Consolidated Ute Agency; RG 75; NAD.

23. Joseph Has the Eagle Industrial Survey, 1925; p. 1; Box 1; Industrial Surveys, 1925 (8NS-75-96-466); Fort Belknap Agency; RG 75; NAD.

24. Merlin Shield Industrial Survey, 1925; p. 1; Box 1; Industrial Surveys, 1925 (8NS-75-96-466); Fort Belknap Agency; RG 75; NAD.

25. Alexander Calowahcan Industrial Survey, 1923; p.1; Box 33; Subject Files, 1907–1945 (8NS-75-96-327); Flathead Agency; RG 75; NAD.

26. Wesley Meritt Industrial Survey, 1924; p.1; Box 1; Home Industrial Surveys, 1924 (8NS-75-97-069); Northern Cheyenne Agency; RG 75; NAD.

27. Blackbull Industrial Survey, 1921 p.1; Box 1; Blackfeet Industrial Survey, 1921 (Entry 64); Blackfeet Agency; RG 75; NAD.

28. Adam Spoonhunter Industrial Survey, 1925; p. 1–2; Arapaho Family Histories, 1925 (Entry 58); Wind River Agency; RG 75; NAD.