Tracing an Atrocity

How an Obscure Affidavit in the National Archives Unraveled a Historical Mystery

Summer 2017, Vol. 49, No. 2

By John DeSantis

© 2017 by John DeSantis

In 1995 I left New York City, where I grew up and whose streets I had come to know too well.

Tired of gathering facts about the Big Apple’s homicide du jour or standing in at press conferences for reporters more experienced, I accepted a position at a small daily newspaper in south Louisiana, about 60 miles southwest of New Orleans, called the Houma Courier.

Local government machinations, the region’s rich Cajun culture, the trials of the area’s commercial fishermen, and a parade of social justice issues kept me busy and fulfilled.

But the story I had the greatest desire to tell was maddeningly elusive. For more than 20 years I sought proof of a vigilante killing in the neighboring town of Thibodaux—beyond quotes from some letters and a few other historical scraps already reported in scholarly works. Even more difficult was finding someone—anyone—with a family tie to the incident, referred to in recent times as the Thibodaux Massacre.

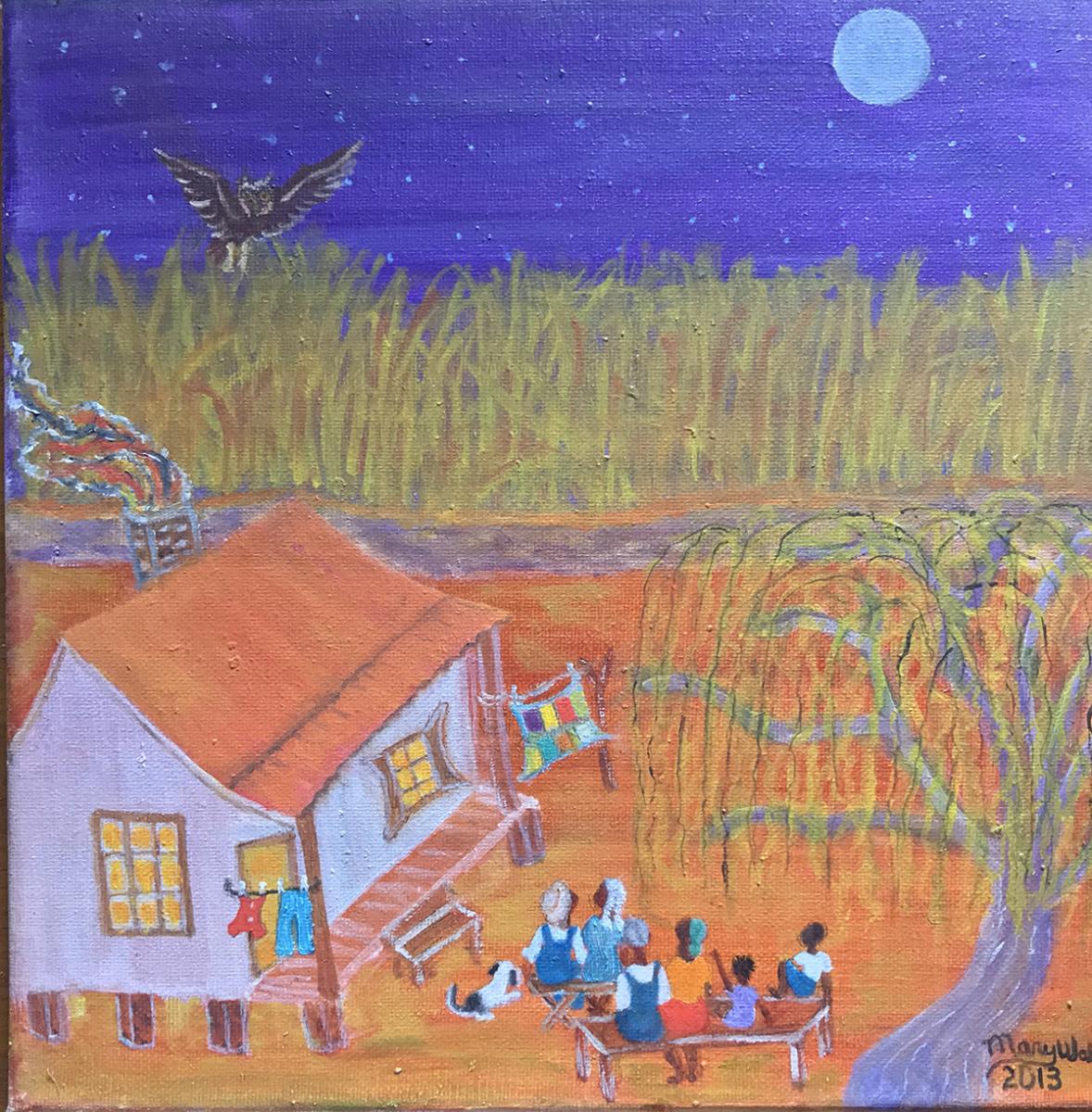

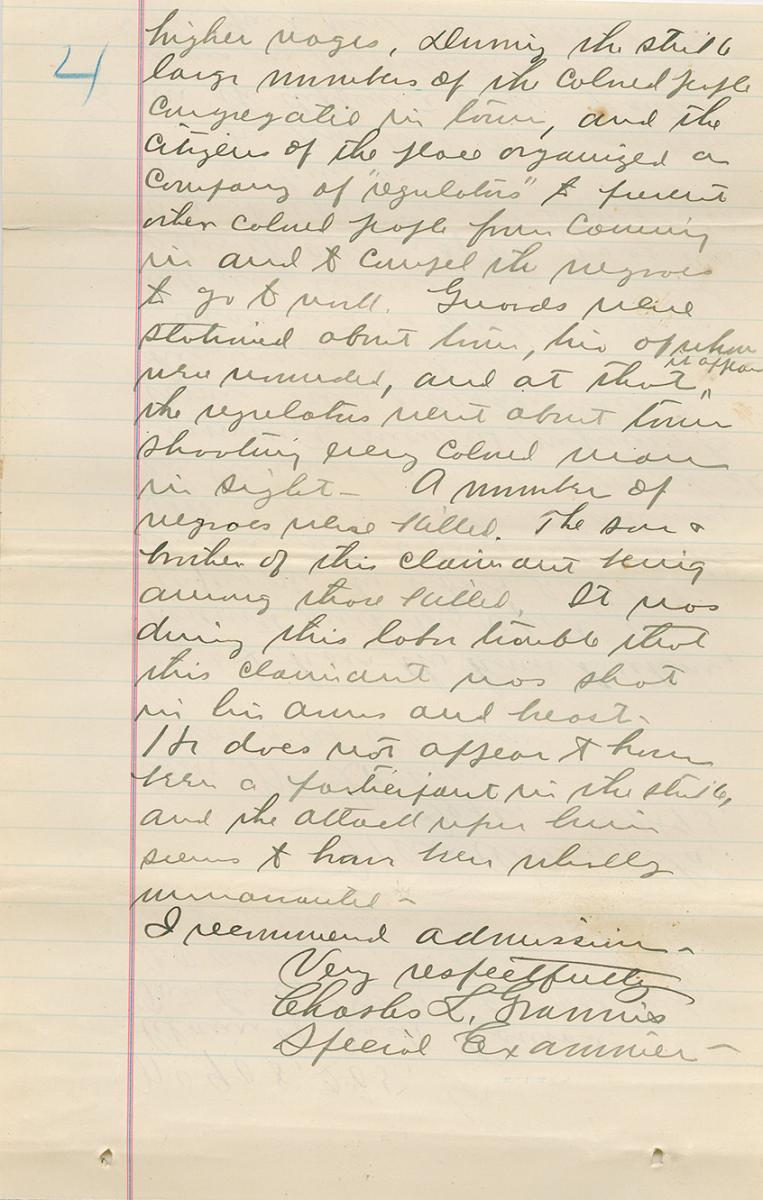

I would later learn conclusively that anywhere from 30 to 60 striking black sugarcane workers, their supporters, and family members were shot to death by white vigilantes on November 23, 1887.

I had no idea while attempting to harvest facts surrounding this tragedy that a book would result. And I never dreamed that the obscure record of an equally obscure Army private in the National Archives would provide the key for unlocking truth.

“A Story Nobody Wanted Told”

Shortly after my arrival in the bayou country, I was told by Burnell Tolbert, president of the Lafourche Parish, Louisiana, branch of the NAACP, that something bad had happened in Thibodaux. He wasn’t sure of the details.

“It’s a story nobody wanted told,” he said.

But I wanted to tell it. A small local newspaper enabling spiritual justice by telling a tale of events hidden so long ago was an appealing thought.

An unsigned letter in a local newspaper printed after the massacre occurred—with the sparsest of details—marks a clear desire at the time for silence.

“Better for all concerned that this page be torn out of our history, rather than try to explain,” it reads.

Missing most of all was any clue to identities of the dead. In the old newspaper accounts, victim names were never mentioned, beyond collective references to “the negroes.” Without discovering such names, or some other information that had not already been reported, an ethical dilemma loomed. Telling such a horrendous story to residents of the place where it occurred in the pages of a local newspaper could have serious repercussions. Bitterness could result, perhaps even local racial conflict. If a modern newspaper was to tell this story, there had to be a compelling reason for doing so. So, my quest continued for many years, with nothing new to report.

Killings in South Carolina Prompt Change in Attitudes

That aspect changed in 2015, however, after shots fired inside “Mother” Emmanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, forced the nation into a new racial dialogue.

The tragedy in Charleston, some community leaders in Thibodaux said, opened a window for telling the Thibodaux story. If Americans were reaching across the divide of race, it seemed, then perhaps the time had come within that context for Thibodaux to confront its past as well.

Once a thriving center of sugarcane production, Thibodaux’s chief industries now are health care, social assistance, education—as home to Nicholls State University—and retail trades. Its roughly 15,000 people are about 62 percent white and 32 percent black, with the remainder Hispanic. Per capita income stands at just under $40,000. But per capita income for whites, at around $35,000, is double that for blacks, which is estimated at around $15,000. Most of the people are Catholic.

Race relations there are vastly improved from what they once were, but tension still exists.

“The city’s administration has yet to hire a black department head, and when they are asked about this, they give no answers,” Charles Mosley, a retired educator, told me on more than one occasion.

The Rev. Nelson Dan Taylor, Sr., pastor of Allen Chapel A.M.E. Church in Thibodaux, was fascinated and disturbed by the Thibodaux Massacre from the time of his arrival there from Baton Rouge in 2006.

“It resonates in a very cataclysmic way in that it was an act of suppression and terror, economic, political, and social,” said Taylor, who is also a civil rights lawyer.

“That one event had to have shaken this community, contributing to a spirit of despair and hopelessness that I think you still see,” Taylor said. “Nobody confronts anything here. We need to discuss how it was and how we got to where we are today. The story of what happened in Thibodaux is intolerable, and we only know bits and pieces of it. It is so horrible historically that I think people don’t want to remember, both white and black.”

A Door-to-Door Campaign to Solicit Oral Histories

With his words leading the account—explaining the reason the story was being told—the newspaper I now work for, the Times of Houma and Thibodaux, published my best effort to share uncomfortable news from 130 years ago with the residents of Thibodaux and surrounding communities.

I went door to door to further seek out oral histories. At one house in southern Thibodaux, I spoke with a black family whose members gathered under their carport after a workday at their various jobs. Three generations said they had never heard of such a thing. An elderly woman, seated on a rear stoop, raised her head and looked straight at me.

“White people were riding through town,” she said in a creaky voice. “They shot the black people, fired into houses.”

Gently, I asked this woman where she had gained such knowledge.

“I ain’t saying nothing else,” she said. “I don’t want to get in no trouble.”

Labor actions had occurred on several Louisiana sugar plantations after the Civil War, with minimal results. The chief complaints of workers were continuing low wages—most earned between 50 and 65 cents a day—and the use of plantation scrip for payment.

The scrip, IOUs on cards or tokens, could be used for merchandise at the plantation store, often at inflated prices. It acted as invisible chains for workers who were supposed to be free, but could not ever put enough money together to leave the plantation.

The Knights of Labor (KOL), an integrated labor organization based in Philadelphia, had organized railroads with some success. Realizing that the plantation-bound sugar workers were ripe for organizing on a larger scale, the KOL connected with plantation school teachers, ministers, freemasons, and even local black barbers, all of whom were held in high regard.

By October 1887, inroads were made in the parishes of Terrebonne, Lafourche, and St. Mary, and a list of demands, composed by a black teacher named Junius Bailey, was delivered to the Louisiana Sugar Planters Association. The demands were refused, and word of a strike began to spread.

On November 1, a strike was called, with the New Orleans Times-Picayune reporting that “the Negroes are stubborn and generally disposed to stand their ground,”

About 10,000 workers laid down their tools on the cusp of the harvest season, vowing to remain in plantation housing

Troops Comb Plantations for Striking Workers

Governor Samuel Douglas McEnery dispatched troops to the region, and they arrived on November 2 from New Orleans and were quartered in Thibodaux. Along with regular arms they brought a Gatling gun, which was placed in front of the Lafourche Parish courthouse.

The troops spread through plantations in the region, evicting the striking workers, who then streamed into Thibodaux as refugees. The troops left around November 18, and in Thibodaux tensions increased.

A local judge, Taylor Beattie, as well as other officials, sanctioned a “vigilance committee” during a fiery meeting at the town hall. Martial law was declared and the entrances to Thibodaux sealed by volunteer sentries. The strikers feared they would be attacked.

Outside the Thibodaux area, agreements were reached with some strikers, who returned to work. But plantations adjacent to the town were still paralyzed, with owners fearing their cane would be lost to a coming freeze.

The situation was being cast more and more as a race war and less as a labor dispute.

In the pre-dawn hours of Wednesday, November 23, two volunteer lookouts enforcing Beattie’s lockdown, Henry Gorman and Joseph Molaison, were shot and wounded by snipers at Thibodaux’s southern end. Townsmen blamed the strikers, and mobs of armed whites took to the streets.

An official account, that “rioters” converged on the scene of the shooting incident, was the prevailing tale told for a century after. Some Louisiana papers reported 25 strikers killed. Some witness accounts suggested as many as 60 dead. No report ever surfaced of any white casualties, other than the two sentries, even among publications sympathetic to strike suppression.

Letters between planter family members, some on file at Louisiana State University, others at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, paint a picture of events far bloodier than press accounts.

The New Orleans Pelican scoffed at the official reports, and a correspondent wrote of “lame men and blind women shot; children and hoary-headed grandsires ruthlessly swept down.”

Newspaper Article Leads to Book Deal

When the story ran in the Times on July 15, 2015, it received a lot of local attention. On November 24, 2015, an acquisitions editor at The History Press called me and said the publishing house was interested in a book on the Thibodaux Massacre.

Would I be interested in writing it?

While I certainly would, I said, there were some things she needed to know. I explained the difficulty I had finding information, particularly oral histories, and how official records could not be located. She said that so long as primary sources of what little was out there were used—and I had already accessed many of those—she was certain the project would work.

Just before the end of the year I signed a contract and got to work.

Clifton Theriot, at that time the chief archivist at Nicholls State University’s Alan J. Ellender Memorial Library, had tried to help me before. But without specific names, there was no way for him to seek any records.

I talked with him—now that there was a May 2016 book deadline in my future—and he made some suggestions. I proceeded to take every single name of any person that was in any historical account that I possessed and made a list. A few days later, Clifton called and said, “I think we have some papers that relate to your project.”

The index of official documents in the Lafourche Parish courthouse that would have related to the events of 1887, I learned, was missing from its shelves, and there was no telling how long it had been gone.

But Clifton Theriot had discovered, in a file at his archive, original documents that were clearly related to the strike and the massacre. Some were irrelevant for my purposes. The appearance of others was nothing less than miraculous.

A yellowed stack of legal-length pages contained the report generated by a hasty coroner’s inquest. Most of it contained a detailed account of the shooting and wounding of the two sentries, with a determination that “a riot” ensued. The names of eight people killed was on the first page. There were no home towns or addresses, just names. Would that be enough to unlock some answers?

File of Jack Conrad Yields Important Information

I got to work as soon as I reached my cluttered desk, checking census records from 1880 and other sources. I was able to find links to a handful of the people, and noticed that most were from Thibodaux. One name stood out. Grant Conrad, who in 1887 would have been 19 years old, had little history other than census records that indicated he started working the cane fields at an early age.

The records—images of pages from the U.S. census accessed through Ancestry.com—showed that Grant’s father was Jack Conrad and his mother was Mary Conrad, also field workers. My fingers flew across my keyboard as I tried to find more about the father, and the diligence paid off. A great deal of time had been expended looking up Grant Conrad’s family tree, however. The book had a tight deadline, and I had already drafted a significant portion of it by the time I learned that Grant’s father’s story could be important.

Jack Conrad had a clearly documented history because in 1862—in New Orleans—he had joined the Federal army as a member of the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT).

Nearly 210,000 men of color were members of Lincoln’s army through the course of the Civil War. Their records are kept at the National Archives, and many are retrievable online.

Jack Conrad’s basic information was simple enough. He had been a member of the 85th USCT, whose name was later changed to the 75th. Among the tasks he performed while in service—the remainder of the war following his 1862 mustering in New Orleans—were carpenter, cook, and sentry. That information did not appear relevant to the massacre.

But there was more to Jack Conrad’s file than what was available online. The records indicated that there was somewhere in the Archives a widow’s pension file that referenced a disability pension. I wasn’t certain what type of pension or how it related to anything I was researching. But just in case the pension records contained information about Jack Conrad or his family, it seemed like a good idea to find out. I copied down the numbers, did some web searches, and made several telephone calls to experts, including personnel at the National Archives familiar with Civil War records.

Patiently and thoroughly, they explained to me that whatever records existed could hold a lot of information about Mr. Conrad. There were, I learned, several types of pensions for Civil War veterans who fought for the Union side, and that the records involved a lot more than payouts for war-related disabilities. For a period of time, the U.S. government provided for its veterans who could not work due to disability that resulted from injury or sickness that occurred after military service.

Mary Conrad Seeks Jack’s Death Benefit

Through experts at the National Archives and further research, I learned that the federal 1890 Disability Pension Act allowed claims by veterans for injuries not related to military service so long as they were not caused by “vicious habits or gross carelessness.”

Something had to have happened to this Jack Conrad, though I wasn’t quite sure what.

Archives staff told me that such files were often very detailed, containing quite a bit of biographical information. Some was required to prove that the claimant was who he said he was. Perhaps, I thought, Jack Conrad might have mentioned to a pension examiner that he had a son who was killed in 1887, possibly providing details. If nothing else, I might learn whether Grant Conrad was named for Gen. U. S. Grant. It would be a biographical tidbit relevant to the book.

Rather than travel to Washington, D.C., myself, I looked for a researcher based there, familiar with the pension files, to actually pull them and give me a sense of whether they contained anything useful. I gave her the file numbers for Jack Conrad, and she got to work.

A week later, she told me that the file for Jack Conrad was unusually large. I got the first batch of 60 pages in another week, on April 6, and was told there were 140 remaining.

The first batch consisted mostly of communications between federal officials and the widow of Jack Conrad, who had died in 1897. Mary Conrad was seeking his death benefit. There were a few documents, however, that were intriguing. Yes, there was mention of Grant Conrad and that he had been killed during an 1887 “riot” in Lafourche Parish. On some documents there was also some mention of injuries Jack Conrad suffered.

Figuratively on pins and needles—with a May 6 book deadline looming—I could no longer focus on writing. I was in a state of suspended animation.

Finally: Affidavit Reveals Details of Strikers’ Killings

On the morning of April 11, I received the remainder of Jack Conrad’s file and was dumbstruck.

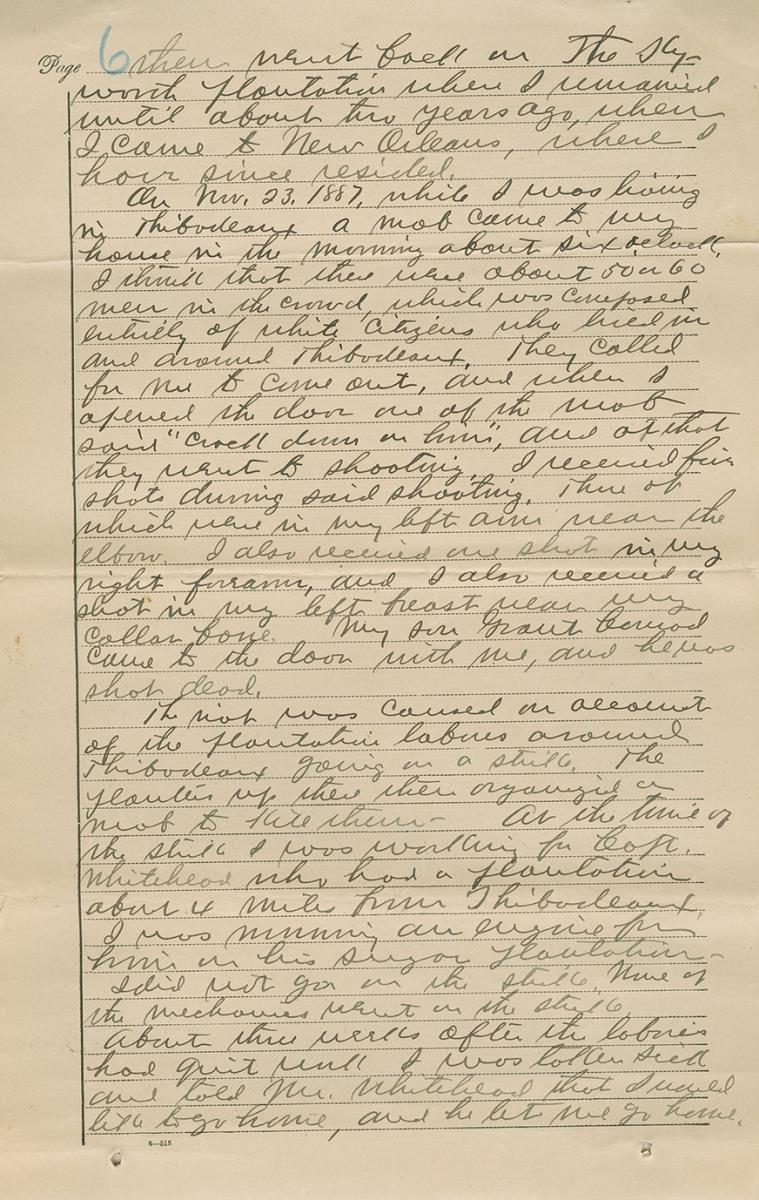

In the handwriting of a government examiner was an affidavit from Jack Conrad himself, who single-handedly verified accounts that the shootings were wanton and not limited to leaders of the strike.

He said he was sleeping in the house he rented in back-of-town Thibodaux when a commotion awoke him.

“I think there were about 50 or 60 men in the crowd, which was comprised entirely of white citizens who lived in and around Thibodaux,” Jack Conrad said. “When I opened the door one of the mob said ‘crack down on him’ and at that they went to shooting.”

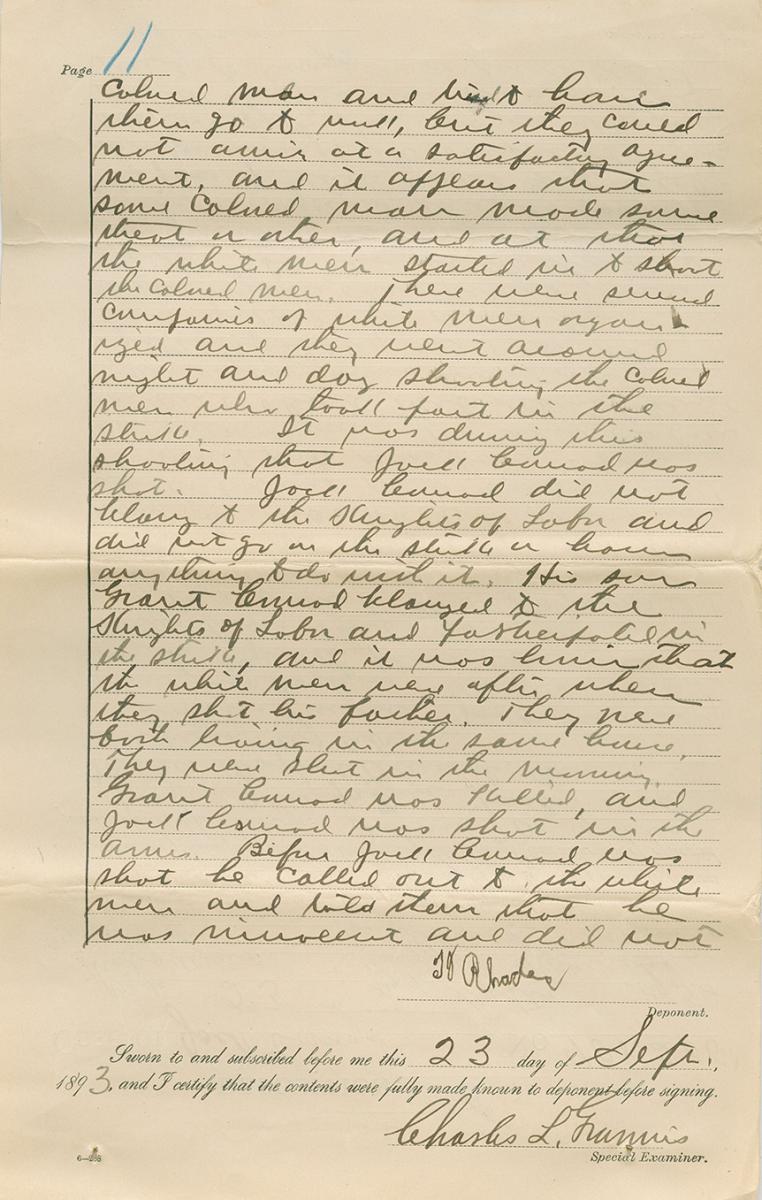

Jack, his son Grant, and brother-in-law Marcelin were told to line up, and they began to run. Grant was gunned down behind a water barrel, Marcelin Weldon was shot as he ran in another direction, and Jack himself took cover under his house as the gunmen continued shooting, leaving to go to another house after they presumed him dead. He was hit by gunfire that shattered bones in his upper body, four shots altogether, a doctor’s diagram in the file clearly shows.

According to accounts from witnesses, also contained in the Conrad files, the shooting went on for more than two hours. Among those witnesses was the Rev. Thomas Jefferson Rhodes, pastor of Thibodaux’s Moses Baptist Church.

Jack Conrad was not on strike, although information in the files indicates Grant had walked off his field hand job.

What the files contained that was of greatest importance was a first-ever account of the violence from the voices of black people who were subjected to it and who witnessed it. Combined with other evidence, the picture that emerges is clear. The Thibodaux Massacre was a horrendous, lengthy shooting spree. The terrorism was so effective that no attempts to organize Louisiana’s sugar fields emerged for more than a half century to come.

Acting with haste, I reorganized the book, beginning with an account drawn from the Conrad files of the scene outside his house. The information in them allowed me to tell the story of the Thibodaux Massacre using Jack Conrad’s life as a touchstone of each era covered.

Descendants of Jack Conrad Learn of Eyewitness Account

I couldn’t help but be haunted by his story. Here was a man who was born a slave, joined the Union Army to fight for his own freedom—the 75th USCT saw heavy action at the decisive Battle of Port Hudson, north of Baton Rouge—and remained with his unit till the end of the war.

Afterward, he returned to the fields where he was once a slave, where little changed. His former adversaries on the battlefield had returned 25 years later with a vengeance to his very home, killing his son in front of his eyes.

Jack Conrad’s story covers the experience of Louisiana blacks before, during, and after the war that was said to have set them free, and is an integral part of the story the book tells.

Caught up in the limbo between the time edits were done and the expected November 2016 release of the book, I continued attempts to find Jack Conrad’s descendants. Checking his files again, I found correspondence from 1924 that contained a version of his daughter’s name (Clara) that was different from what the census records—and her own affidavit as a witness to her father’s shooting—had indicated. I returned to the census files and located her, then followed through with obituaries through ensuing decades showing how the family had grown through several generations.

During Labor Day weekend, I contacted Sylvester Jackson, a retired U.S. airman living in Thibodaux who—if my research was correct—would have been Jack Conrad’s great-grandson.

“I thought this man who called me was trying to sell me something,” the soft-spoken, dignified veteran later told a crowd of people at the launch of the book, an event held at Nicholls State University. He had not known of Jack Conrad; the family tree he was aware of went back only as far as Jack’s daughter, Clara. I spent an hour on the telephone with him and told him of his great-grandfather’s life and times.

A great-great granddaughter, Wiletta Ferdinand, whose name and telephone number were given to me by Sylvester Jackson, was my next call.

“My family and I are so grateful to you for giving us this information. We do not feel you are dredging up the past, but putting a shining light on our history that otherwise we would not have known,” she later said. “Jack wanted us to know what happened and to further explain why we are so strong as a family because we have his blood running through our veins. This is not just our story; this is Thibodaux's story as well.”

A Postscript

Since the book’s release, people are talking about the Thibodaux Massacre in Thibodaux. Members of black families who, it turns out, did have some oral history passed down to them, are talking freely. I learned from community elders that the lot where victims are believed to lie in a mass grave had been a burying place for mules and other beasts of burden.

If they are there, those victims will be able to tell their stories too. The University of Louisiana at Lafayette has advanced a proposal to have their archaeologists explore the area for evidence of human remains. The Louisiana 1887 Memorial Committee, a nonprofit organization, is in the process of raising money to pay the bills, and the project could begin as soon as autumn 2017. If the results are positive, plans are already being made for return of those remains to Thibodaux after examination, for proper burial in sacred ground by members of the community willing to recognize its role in an ugly history.

The story could have been told without Jack Conrad’s files, certainly. I was prepared to do just that. But the discovery of the documents lends an entirely new element to the history. Because of information contained in the book, an American flag was flown over the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., at the request of Representative Cedric Richmond (D-New Orleans). The certificate that Wiletta Ferdinand has since received says it was done to honor the memory of Jack Conrad and other victims of the Thibodaux Massacre.

John DeSantis began his reporting career in the early 1980s in New York City, writing for United Press International, various small newspapers, and for the New York Times and the Washington Post. He is the senior staff writer at the Times of Houma (Louisiana). He has published two prior books: For the Color of His Skin: The Murder of Yusuf Hawkins and the Trial of Bensonhurst and the New Untouchables: How America Sanctions Police Violence. He lives in Bourg, Louisiana.

Note on Sources

The Thibodaux Massacre: Racial Violence and the 1887 Sugar Cane Labor Strike, (History Press, 2016) has been favorably reviewed and received recognition for shedding welcome light on a largely hidden piece of history. Since its completion, I have been able to contact descendants of that soldier, allowing them to connect with an ancestor they never knew existed, and to the history in which he played a tragic role.

To learn more about efforts to locate victims of the Thibodaux Massacre, visit www.La1887.org

I want to thank Amanda Irle, an acquisitions editor at The History Press, for her help in getting this book published by The History Press.

Although this article focuses on my own research, none of the project would have been possible without the scholarship of others, which gave me enough insight into the Thibodaux Massacre to write an article on the event in the Times of Houma.

John C. Rodrigue’s Reconstruction in the Cane Fields (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001), Rebecca J. Scott’s Degrees of Freedom: Louisiana and Cuba after Slavery (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2005) and From Slavery to Emancipation in the Atlantic World, edited by Sylvia R. Frey and Betty Wood (London: Routledge, 2013) are among the most authoritative of these.

An article by Jeffrey Gould, “The Strike of 1887: Louisiana Sugar War” in the November-December 1984 issue of Southern Exposure, provides a concise history of the strike leading to the massacre.

Quotes appearing in this article from the Rev. Nelson Dan Taylor and from a woman who expressed family recollections are taken from the Times article, which was published July 14, 2015.

The research on the Jack Conrad file was performed by Dawn Chitty, education director at the African-American Civil War Museum in Washington, D.C. Other information in this article is culled from The Thibodaux Massacre: Racial Violence and the 1887 Sugar Cane Labor Strike (Charleston S.C.: The History Press, 2016)

Valuable information was obtained in the Jack Conrad File, #908205 filed January 31, 1890, 84th U.S. Colored Infantry, combined with #862005, widow’s pension for Mary Conrad, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15, National Archives, Washington, D.C.