The Nuremberg Laws

Archives Receives Original Nazi Documents That “Legalized” Persecution of Jews

Winter 2010, Vol. 42, No. 4

By Greg Bradsher

It was in Nuremberg, officially designated as the "City of the Reich Party Rallies," in the province of Bavaria, where Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party in 1935 changed the status of German Jews to that of Jews in Germany, thus "legally" establishing the framework that eventually led to the Holocaust.

Ten years later, it would also be in Nuremberg, now nearly destroyed by British and American heavy bombing, where surviving prominent Nazi leaders were put on trial for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The war in Europe ended in May 1945, and soon the attention of the Allies turned to prosecuting those Third Reich leaders who had been responsible for, among other things, the persecution of the Jews and the Holocaust.

The trials began November 20, 1945, in Nuremberg's Palace of Justice, which had somehow survived the intense Allied bombings of 1944 and 1945.

The next day, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, named by President Harry S. Truman as the U.S. chief counsel for the prosecution of Axis criminality, made his opening statement to the International Military Tribunal.

"The most serious actions against Jews were outside of any law, but the law itself was employed to some extent. They were the infamous Nuremberg decrees of September 15, 1935," Jackson said.

The so-called "Nuremberg Laws"— a crucial step in Nazi racial laws that led to the marginalization of German Jews and ultimately to their segregation, confinement, and extermination—were key pieces of evidence in the trials, which resulted in 12 death sentences and life or long sentences for other Third Reich leaders.

But the prosecution was forced to use images of the laws from the official printed version, for the original copies were nowhere to be found.

However, they had been found earlier, by U.S. counter-intelligence troops, who passed them up the line until they came to the Third Army's commander, Gen. George S. Patton, Jr. The general took them home to California. There, they remained for decades, their existence not revealed until 1999.

Finally, this past summer, the original copies of the laws, signed by Hitler and other Nazi leaders, were transferred to the National Archives.

Third Reich Began Persecutions

Years Before Laws Enacted in 1935

The Nuremberg Laws made official the Nazi persecution of the Jews, but the “legal” attack on the Jews actually began two years earlier.

After the Nazis took power in Germany in 1933, they became increasingly engaged in activities involving the persecution of the Jewish and other minority populations. They did it under the color of law, using official decrees as a weapon against the Jews.

In 1933 Jews were denied the right to hold public office or civil service positions; Jewish immigrants were denaturalized; Jews were denied employment by the press and radio; and Jews were excluded from farming. The following year, Jews were excluded from stock exchanges and stock brokerage.

During these years, when the Nazi regime was still rather shaky and the Nazis feared opposition from within and resistance from without, they did nothing drastic, and the first measures appeared, in relative terms, rather mild.

After Germany publicly announced in May 1935 its rearmament in violation of the Versailles Treaty, Nazi party radicals began more forcibly demanding that Hitler, the party, and the government take more drastic measures against the Jews. They wanted to completely segregate them from the social, political, and economic life of Germany. These demands increased as the summer progressed.

On August 20, 1935, the U.S. embassy in Berlin reported to the secretary of state:

To sum up the Jewish situation at the moment, it may be said that the whole movement of the Party is one of preparing itself and the people for general drastic and so-called legal action to be announced in the near future probably following the Party Congress to be held in Nuremberg beginning on September 10th. One has only to review the statements made by important leaders since the end of the Party's summer solstice to realize the trend of affairs.

James G. McDonald, high commissioner for refugees under the League of Nations, then in Berlin, wrote in his diary August 22 that "New legislation is imminent, but it is difficult to tell exactly what the provisions will be. Certainly, they will tend further to differentiate the Jews from the mass of Germans and to disadvantage them in new ways."

William E. Dodd, the American ambassador to Germany, on September 7 sent a long dispatch to the secretary of state regarding current development in the "Jewish Situation." He reported "it appears that even now discussions are still continuing in the highest circles respecting the policy to be evolved at the Nuremberg party Congress." He added:

It is believed that a declaration respecting the Jews will be made at Nuremberg which will be followed by the announcement at the Congress itself, or shortly thereafter, or a body of legislation whose ultimate character will depend upon the result of the discussions now in progress. Either one or the other will probably contain drastic features to appease the radicals but may be offset by certain appearances of moderation to be emphasized later to facilitate such dealing abroad. . . . An idea that may influence policy at Nuremberg, and in any case now seems to be uppermost in the minds of Party extremists, is that, however drastic the measures adopted, they will be formally rooted in law, and that the sanctity with which law is regarded, and the discipline with which it is observed in Germany, may impress foreign opinion favorably.

On September 9, McDonald wrote Felix Warburg, a major American Jewish leader, that he was unable to get a clear picture what may be expected in the threatened new legislation, but "One can only be certain that the result will be to penalize the Jews in various ways and on the basis of pseudo-legality, which causes grim forebodings."

Nazi Rally in Nuremberg

Hailed Passage of the Laws

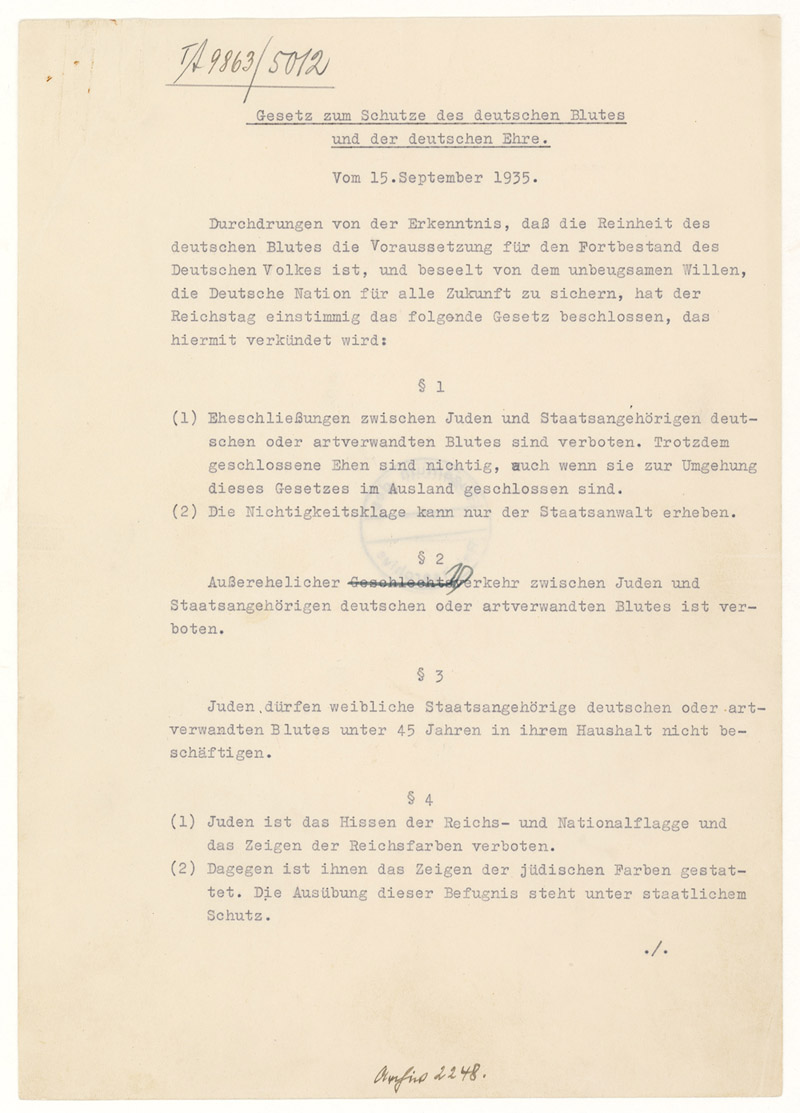

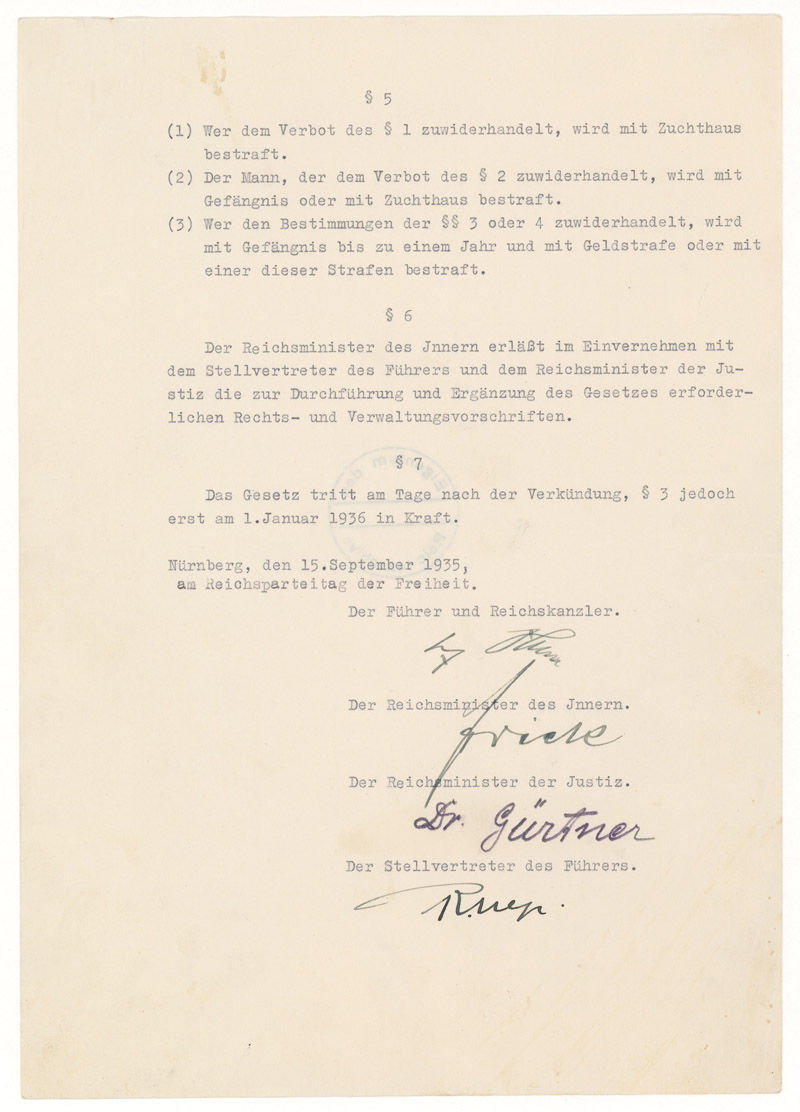

At their annual rally held in Nuremberg on September 15, Nazi party leaders announced, after the Reichstag had adopted them, new laws that institutionalized many of the racial theories underpinning Nazi ideology.

The so-called Nuremberg Laws, signed by Hitler and several other Nazi officials, were the cornerstone of the legalized persecution of Jews in Germany. They stripped German Jews of their German citizenship, barred marriage and "extramarital sexual intercourse" between Jews and other Germans, and barred Jews from flying the German flag, which would now be the swastika.

On September 16, Ambassador Dodd sent a cable to the secretary of state about the Nuremberg Laws. He wrote:

So far it is only possible to say that main trend of Nuremberg congress was to cater to radical sentiment within the Party. The laws passed last night concerning citizenship, the swastika as national flag and for protection of German blood and honor (by means of preventing marriage and sexual intercourse between Aryan and Jews and flying of the German flag by the latter) obviously need further definition and Foreign Office advised waiting for executive supplementary regulations. [These, issued on November 14, provided specific definitions of who a Jew was.]

Dodd followed up the next day with a dispatch to the secretary of state regarding the Nuremberg Party Congress: "Race propaganda and psychology ran through practically all the speeches like a scarlet thread, obviously in preparation for the laws that were to be adopted by the Reichstag."

He added: "The new laws against the Jews deceive very few people that the last word has been said on that question or that new discriminatory measures will not eventually follow within the limit of what is possible without bringing about too great a disturbance in business."

On September 19, Dodd sent the secretary of state two copies of the Reichsgestzblatt [Reich Law Gazette] of September 16, which contained the Nuremberg Laws and also included translations of them.

In transmitting them, Dodd wrote: "The anti-Jewish legislation should be sufficiently severe to please Party extremists for some time."

They were not. More persecutions followed in the years before World War II began in 1939. The extermination of the Jews and others followed, not only in Germany, but through most of Europe.

Original Nuremberg Documents

Are Found, But Then Disappear

The Moscow Declaration of 1943, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Marshal Josef Stalin, took note of the atrocities perpetrated by the Germans and laid down the policy that the major criminals would “be punished by the joint decision of the Governments of the Allies."

But first the war had to be concluded before the Moscow Declaration could be implemented.

As the Allied forces overran Germany in April 1945, on April 20 (Hitler's birthday), elements of the Third and 45th Infantry divisions of the U.S. Seventh Army entered Nuremberg and after hard fighting effectively secured the town. A week later, Hitler committed suicide in Berlin, and the week after that, the Germans surrendered.

Now the Moscow Declaration could be put into effect.

Meanwhile, in late April 1945, M.Sgt. Martin Dannenberg, leading the 203rd U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) Detachment, working with the U.S. Third Army, was roaming through Bavaria with two other men, carrying out various CIC assignments.

An informant led him and his team to a bank vault in the town of Eichstaett, about 45 miles due south of Nuremberg. There, a German financial official who had a key opened the vault, then handed over to the American soldiers some documents in a yellow envelope, sealed with red wax swastikas.

Dannenberg slit the top of the envelope and pulled the documents out. The first thing he saw was the signature "Adolf Hitler."

Sgt. Frank Perls, a German-born Jew (though baptized as a Protestant) who joined the U.S. Army in 1943 after fleeing his homeland in 1933, was one of two men accompanying Dannenberg. Translating the documents, Perls quickly realized they were the infamous Nuremberg Laws.

Dannenberg turned them over to his commanding officer, who ordered Dannenberg and Perls to deliver them to the U.S. Third Army commander, Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.

War Crimes Trials Begin

—Without Original Copies

On May 2, less than a week after the CIC special agents found the Nuremberg Laws and a few days before the war in Europe ended, Truman appointed Associate Justice Jackson as chief of counsel for the United States in its prosecution of the Allied case against the major Axis war criminals.

During the next three months, Jackson spent most of the time in London negotiating with the British, French, and Soviet representatives over an agreement to prosecute the major Nazi war criminals before an international tribunal. They would reach agreement on August 8.

Meanwhile, immediately after Jackson's appointment, the staff of the Office of the United States Chief of Counsel, which grew to more than 600 personnel, started collecting documentary evidence that could be used by the prosecutors.

Among the evidence gathered were volumes of the Reichsgestzblatt, which contained various German laws, decrees, and regulations, including those relating to the persecution of the Jews.

In the September 16, 1935, edition were the Nuremberg Laws, which had been adopted by the Reichstag the previous day and promulgated by its president, Hermann Goering. Photostats and translations of them were placed in the U.S. evidence file and eventually made available to the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.

The prosecutors may have wished they had the original laws themselves, as they would have made for dramatic evidence since two of the defendants, Wilhelm Frick and Rudolf Hess, had signed them. But, unfortunately, they did not. General Patton had them.

Patton Ignores Orders,Takes

Original Copies To California

Patton, like so many of his soldiers, was a souvenir hunter.

Rather than ensuring the copies of the Nuremberg Laws that he received from Dannenberg and Perls were delivered to the appropriate authorities, he took them home to California after the war in Europe was over.

In doing so, Patton was violating Supreme Headquarters Allied Expedition Forces (SHAEF) and 12th Army Group directives of November 9 and 23, 1944, issued by Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower and Omar N. Bradley, respectively, regarding seizing and holding Nazi party and German government records.

Six months after Patton took the Nuremberg Laws to California, the trial began. Justice Jackson, in his opening statement to the court on November 21, as noted earlier, referenced the Nuremberg Laws, citing the version published in the Reichsgestzblatt of 1935.

During the tribunal's December 13 session, an assistant trial counsel for the United States addressed the court about the Nazi persecution of the Jews. In making his presentation, he said: "When the Nazi Party gained control of the German State, a new and terrible weapon against the Jews was placed within their grasp, the power to apply the force of the state against them. This was done by the issuance of decrees."

He then proceeded to list them, including the Nuremberg Laws as published in the 1935 Reichsgestzblatt. After discussing them, he asked the court to take judicial notice of the published decrees. From a legal perspective, theReichsgestzblatt was certainly authoritative and acceptable to the tribunal under its charter regarding rules of evidence, but it certainly would have been more dramatic and effective to have confronted the defendants with the originals, as the prosecutors did with other documents.

The trial would go on another 10 months, with references often made to the Nuremberg Laws. On September 30 and October 1, 1946, the tribunal rendered judgment. Of the three defendants most closely associated with the Nuremberg Laws, Herman Goering and Wilhelm Frick were sentenced to death, and Rudolf Hess was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Missing Documents Reemerge.

Now in the National Archives

A week later, with his work over, Justice Jackson sent President Truman a final report about his activities and noted that the war crimes documentation, including captured records, was the property of the United States and that an agency should take custody of it on behalf of the United States.

"The matter," he wrote, "is of such importance as to warrant calling it to your attention."

Two months later, the records of the U.S. Counsel for the Prosecution of Axis Criminality were offered to the National Archives, and in 1947 the National Archives accessioned them. Within the records are photostatic and translated copies of the Nuremberg Laws as published in the Reichsgestzblatt and referred to during the trial.

General Patton had deposited the original Nuremberg Laws at the Huntington Library, near his home in the Los Angeles area in June 1945; Patton died as a result of injuries received in an auto accident in Germany in December 1945 and had left no instructions regarding the laws.

Their existence at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens was not revealed until 1999, when they went on display for 10 years at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles until late 2009.

In the summer of 2010, the National Archives accepted donation from the Huntington Library of the original Nuremberg Laws—63 years later than they would have if Patton had turned them over to the appropriate authorities.

Greg Bradsher, an archivist at the National Archives and Records Administration, specializes in World War II intelligence, looted assets, and war crimes. His previous contributions to Prologue have included articles the discovery of Nazi gold in the Merkers Mine (Spring 1999); the story of Fritz Kolbe, 1900–1943 (Spring 2002); Japan's secret "Z Plan" in 1944 (Fall 2005); Founding Father Elbridge Gerry (Spring 2006); the third Archivist of the United States, Wayne Grover (Winter 2009); and Operation Blissful, a World War II diversionary attack on an island in the Pacific (Fall 2010).

Note on Sources

Published in 42 volumes, the Trial of the Major War Criminals before The International Military Tribunal, Nuremberg 14 November 1945–1 October 1946 (Nuremberg: International Military Tribunal, Nuremberg, 1947–1949), contains the day-to-day proceedings of the tribunal and documents offered in evidence by the prosecution and defense.

Office of United States Chief of Counsel for Prosecution of Axis Criminality, Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression (Washington, D.C. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946), vol. I, Chapter 12, contains information about documents, including those not introduced as evidence during the International Military Tribunal, relating to the persecution of the Jews in Germany.

The State Department's Central Decimal File, 1930–1939 (General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59), under decimals 862.00 and 862.4016, contains reports on political developments in Germany and the persecution of German Jews. Also useful regarding the persecution of the Jews in Germany beginning in 1935 is Richard Breitman, Barbara McDonald Stewart, and Severin Hochberg, eds., Refugees and Rescue: The Diaries and Papers of James G. McDonald 1935–1945 (Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press, in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, 2009).

Useful for understanding the adoption of the Nuremberg Laws, their discovery by the Counterintelligence Corps team in 1945, General Patton's acquisition and disposition of them in 1945, their custody by the Huntington Library (1945–1999), and their subsequent exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center is Anthony M. Platt with Cecilia E. O'Leary, Bloodlines: Recovering Hitler's Nuremberg Laws, From Patton's Trophy to Public Memorial (Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2006).