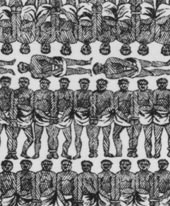

By the late 18th and early 19th century, the life-long enslavement of Africans and African Americans defined the country’s social, political, and economic character. Slavery was considered a necessary evil by some and a right of property entitlement by others.

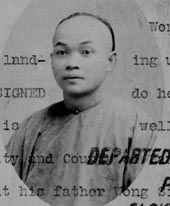

The 13th Amendment (1865) abolished slavery; the 14th Amendment (1868) defined citizenship; the 15th Amendment (1870) protected voting rights. These initial constitutional gains were soon lost as other economic systems — peonage (involuntary servitude) and share-cropping — eroded individual rights. Other ethnic groups, such as the Chinese, also faced discrimination and curtailed rights.

With an unprecedented wave of immigration occurring in the late 19th and early 20th century, the face of America changed. New immigrants and long-term residents struggled to assimilate as well as overcome social inequalities and injustices.

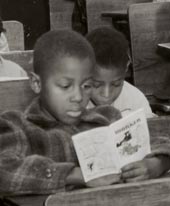

World War II forced the United States to reconsider how it defined personal freedoms and equality under the law. In countless acts of protest, organizations and individuals continued the struggle for equal rights. Court rulings and legislation, such as the Civil Rights Act (1964), strengthened the march to equality.

Fighting to end the policy of a “separate but equal” educational system, Brown v. Board of Education consolidated five cases filed in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and Delaware. The case claimed that the “separate but equal” ruling violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The unanimous Supreme Court decision served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement.