Section V: We Shall Overcome

Fighting to end the policy of a “separate but equal” educational system, Brown v. Board of Education consolidated five cases filed in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and Delaware. The case claimed that the “separate but equal” ruling violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The unanimous Supreme Court decision served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement.

Judgment, Brown v. Board of Education,

May 31, 1955 [one with facsimile]

Case File for Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka et al., Appellate Jurisdiction Case Files National Archives, Records of the Supreme Court of the United States, Record Group 267 (National Archives Identifier 301669)

In its unanimous opinion of May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ended the “separate but equal” precedent set nearly 60 years earlier. A year later in what is now referred to as “Brown II,” Chief Justice Warren required that the students be “admit[ted] to public schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed.”

Briggs v. Elliot, Complaint against Segregated South Carolina Schools, December 19, 1950

Briggs vs Elliott, Civil 2657, Civil Cases Files National Archives, Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21 (National Archives Identifier 641621)

Twenty African American parents from Clarendon County, South Carolina, sought better schools with educational facilities, curricula, equipment, and opportunities equal to those provided for white children and challenged the constitutionality of “separate but equal” practices. This was one of the earliest challenges to public school segregation filed in Federal courts. Over the next five years, plaintiffs lost jobs, homes, and even lives. They were harassed and refused service and credit.

Dissenting Opinion, Briggs v. Elliot,

June 21, 1951

Briggs vs Elliott, Civil 2657, Civil Cases Files National Archives, Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21 (National Archives Identifier 279306)

This case was heard in May 1951 by a panel of three Federal judges, and it was found that “separate but equal” schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment with Judge J. Waites Waring dissenting. The U.S. District Court did rule that the schools attended by African American children were inferior to the white schools, and they ordered the school system to equalize the facilities. But because Briggs v. Elliot challenged the constitutionality of segregation, the case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Judgment, Belton v. Gebhart,

May 31, 1955 (facsimile)

National Archives, Records of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court affirmed the rights of African American children to attend public schools with white children.

Opinion on Writ of Certiorari,

Bolling v. Sharpe, May 31, 1955 (facsimile)

National Archives, Records of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court required admission to public schools on “a racially nondiscriminatory basis,” reversing the ruling of the lower court.

Plaintiffs Exhibit, Davis v. Prince Edward Co., May 1956

Dorothy E. Davis, et al. versus County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, Civil Action No. 1333, Civil Cases Files National Archives, Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21 (National Archives Identifier 279122)

Virginia claimed that education policies, including segregation, were state’s rights under the 10th Amendment. The District Court agreed but decreed that the 14th Amendment guaranteed that facilities had to be equal. After the Brown decision, the lower court reversed itself on the state’s authority over segregation and invalidated part of the Virginia constitution. Regardless, the county school board concluded that everyone was best served “by the separation of races in the public schools,” which led to a resumption of the case.

Opinion, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, August 3, 1951

Civil Cases Files National Archives, Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21 (National Archives Identifier 2641494)

A three-judge panel at the U.S. District Court in Topeka unanimously held that “no willful, intentional or substantial discrimination” existed in Topeka’s schools. The decision was appealed and became part of the groundbreaking Brown v. Board of Education decision.

![[A]dmit to public schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed the parties to these cases. -Brown v. Board of Education Judgment, May 31, 1955](/exhibits/documented-rights/exhibit/section5/images/brown-quote-1.jpg)

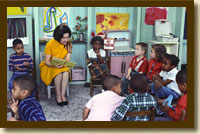

Photograph, Lady Bird Johnson Visiting a Project Head Start Classroom, March 19, 1966

Johnson White House Photographs National Archives, White House Photo Office Collection (National Archives Identifier 596401)

Photograph, First Grade Class, South Pittsburg, Tennessee, December 15, 1948

Photographs Promoting the Use of Electricity National Archives, Records of the Tennessee Valley Authority, Record Group 142 (National Archives Identifier 2641483)

Photograph, Fifth Grade Class, Florence, Alabama, January 31, 1946

Photographs Promoting the Use of Electricity National Archives, Records of the Tennessee Valley Authority, Record Group 142 (National Archives Identifier 2641482)

![Judgment, Brown v. Board of Education, May 31, 1955 [one with-(facsimile)]](/exhibits/documented-rights/exhibit/section5/images/brown-judgment-sm.jpg)