An American Epic

Herbert Hoover and Belgian Relief in World War I

Spring 1989, Vol. 21, No. 1

By George H. Nash

© 1989 by George H. Nash

Senator Everett Dirksen of Illinois was once asked by a group of junior high school students to define diplomacy. The senator replied: "If I said to my wife, 'You have a face that would stop a thousand clocks,' that would be stupidity. But if I turned to her and said, 'Dear, when I behold you, time stands still,' that's diplomacy!"

The subject of my essay, and of the book that I have just published, is, in a way, diplomacy, but diplomacy of a special sort—indeed, of a character that the world had never seen before. The Life of Herbert Hoover: The Humanitarian, 1914–1917, is also a book about politics, again of a special sort: the politics of philanthropy and humanitarian relief on a scale previously unknown and unimagined. And, of course, my book is the second installment in a biography of one of the least understood of all American leaders.

While preparing this volume, I spent many rewarding days in the research rooms and corridors of the National Archives, where I received the courteous assistance of people like Assistant Archivist for Presidential Libraries John Fawcett and archivists Ronald Swerczek and Gerald Haines. I was drawn here by two superb collections: Record Group 59 (the General Records of the Department of State) and RG 84 (the Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State). Of the latter, two in particular—the files of our embassy in London and legation in Brussels for the years of World War I—proved to be indispensable. And no doubt like innumerable other scholars over the years who have explored these particular treasures, I say: Hurrah for the State Department's decimal file and the access to the past that it facilitates. Would that every other agency of government used a similar classification scheme.

This summer the nations of Europe and North America will recall the seventy-fifth anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. For the people of the United States this commemoration will evoke many images. Of battle sites like Château-Thierry and Belleau Wood. Of soldiers like John J. Pershing and Sergeant York. Of Flanders Fields where poppies grow. Of a musical call to arms, "Over There." For some Americans the remembrance will elicit another image as well: of the grim, chaotic month of August 1914, when the independent kingdom of Belgium courageously resisted an invading German army, only to fall victim to a four-year ordeal of conquest.

One American will be forever linked in history with Belgium's travail in that awful war. His name, of course, is Herbert Hoover. After the battle of the Marne, giant European armies bogged down in the trenches, and famine threatened beleaguered Belgium, a highly industrialized nation of 7 million dependent upon imports for three-quarters of her food. On one side the German army of occupation refused to take responsibility for victualing the civilian population. Let Belgium import food from abroad as she had done before the war, said the Germans. On the other side stood the tightening British naval blockade of Belgian ports. Let the Germans, as occupiers of Belgium, feed its people, said the British. Besides, they argued, how could one be sure that the Germans would not seize imported food for themselves?

As the tense days passed in the early autumn of 1914, food supplies dwindled ominously in Belgium. To the outside world went emissaries pleading for the Allies to permit food to filter through the naval noose. Finally, on October 22, after weeks of negotiations, Herbert Hoover established under diplomatic protection a neutral organization to procure and distribute food to the Belgian populace. Great Britain agreed to let the food pass unmolested through its blockade. Germany in turn promised not to requisition this food destined for helpless noncombatants.

Why Hoover? In the summer of 1914 Herbert Clark Hoover was a prosperous forty-year-old international mining engineer living in London—and dreaming of a career of public service in the United States. This orphaned son of an Iowa blacksmith had come far indeed from his humble beginnings in the American Middle West. Rising rapidly in his chosen profession, by 1914 he directed or in part controlled a worldwide array of mining enterprises that employed a hundred thousand men. "If a man has not made a fortune by 40 he is not worth much," Hoover had said, while still in his thirties. By August 1914 he had achieved his goal yet was not content. "Just making money isn't enough," he confessed to a friend. Instead, he wanted (as he put it) to "get into the big game somewhere." Fascinated by the power of the press to mold and direct public opinion, Hoover that summer was negotiating to purchase a newspaper in California. Events in Europe compelled him to abandon his quest. Had it not been for "the guns of August," he would have entered American public life—and might even be remembered today—as a newspaper magnate.

In the first tumultuous weeks of the war, tens of thousands of American travelers in Europe fled the war-shocked continent for the comparative safety of London—and, they hoped, passage home. It was not as easy as that. Arriving in the British capital, many Yankee tourists found themselves unable to cash their instruments of credit or obtain temporary accommodation, let alone tickets for ships no longer crossing the Atlantic. Responding to the travelers' panic and necessities, Hoover and other American residents of London organized an emergency relief effort that provided food, temporary shelter, and financial assistance to their stranded fellow countrymen. Eventually the passenger ships resumed their sailings, and more than 100,000 weary and frightened travelers headed back to the United States. Hoover's untiring and efficient leadership during the crisis earned him the gratitude of the American ambassador to Great Britain, Walter Hines Page. And when a few weeks later the plight of Belgium became perilous, Ambassador Page and others agreed upon Hoover, a man of demonstrated competence, to administer this new mission of mercy. The globe-trotting mining engineer who had done well, and who now wanted to do good, had found an unexpected entrée into the "big game."

And so began an undertaking unprecedented in world history: an organized rescue of an entire nation from starvation. Initially no one expected this humanitarian task to last more than a few months. Few foresaw the gruesome stalemate that developed on the western front. As Hoover himself later wrote, "The knowledge that we would have to go on for four years, to find a billion dollars, to transport five million tons of concentrated food, to administer rationing, novel relief organization, which went by the name of the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), possessed some of the attributes of a government. It had its own flag, it negotiated "treaties" with the warring European powers, and its leaders parleyed regularly with diplomats and cabinet ministers in several countries. It even had a "pirate" leader in Hoover, who enjoyed price controls, agricultural production, to contend with combatant governments and with world shortages of food and ships, was mercifully hidden from us."

Within a few months Hoover and a team of mostly American volunteers built up what one British government official called "a piratical state organized for benevolence." Indeed, the informal diplomatic immunity and traveled freely through enemy lines—probably the only American citizen permitted to do so in the entire war.

As a historian and biographer of Mr. Hoover, I am particularly impressed by four aspects of his wartime service to the people of Belgium. First, by the sheer complexity and magnitude of the relief commission that he led. Today we are apt to take for granted the prompt intervention of humanitarian agencies in areas of distress, be it a famine in Ethiopia, an earthquake in Mexico, or a typhoon in Bangladesh. In 1914, however, no institution for the succor of Belgium existed; it became Hoover's awesome responsibility to create one.

Consider the array of tasks that the Commission for Relief in Belgium was obliged to perform. First it had to raise money throughout the world—partly through charitable appeals, but primarily, as the war went on, through subsidies from the Allied governments. With this money it had to purchase wheat and other foodstuffs from North America, South America, and Australia. Then it had to arrange for shipping these foodstuffs to Belgium; eventually the CRB had a fleet of several dozen ships continuously at its disposal. When these ships entered the European war zone, they were required to navigate carefully lest they be seized or subjected to submarine attack. And when the food-laden vessels reached the neutral Dutch port of Rotterdam, their cargo had to be unloaded for conveyance by canal into Belgium.

Once inside the occupied country the supplies had to be prepared in mills, dairies, and bakeries for human consumption. Then the food had to be distributed equitably to an anxious population scattered over more than 2,500 villages, cities, and towns. As part of its undertaking, the CRB needed to verify that the daily rations did indeed reach their intended recipients and not the German army of occupation. Working with Hoover and his staff was a vast network of forty thousand Belgian volunteers who handled the distribution of food throughout their land. This parallel Belgian organization was known as the Comité National de Secours et d'Alimentation. At its head were some of the country's most eminent business leaders. In early 1915 Hoover's team was allowed to extend its life-sustaining operations to 2 million desperate French civilians caught behind the German battle lines on the western front. Thus the CRB's work came to encompass a total area of nearly twenty thousand square miles.

The commission's functions were even more complex than this summary suggests. Writing in early 1917, one of the CRB's young supervisory delegates, Joseph C. Green, explained in a letter what providing food to a civil population under enemy control actually entailed:

Take the one item of bread for example. First the [CRB] Provincial Representative has to figure out periodically the exact population of his Province, and the exact quantities of native wheat and rye and of imported wheat and maize on hand. From this he calculates the quantity of imported grain necessary to cover a certain period. This he reports to Brussels, and Brussels to London. London supplies the ships. New York purchases and sees to the loading. Rotterdam tranships into canal barges. In the meantime Brussels has decided upon the exact quantities to be shipped to each mill in the country, and Rotterdam ships accordingly. The provincial man must see to the unloading and the milling. The milling involves questions of percentages of bran and flour, of mixtures of native and foreign grains, of the disposal of byproducts and so on.

And this was just the start:

When the flour is finally milled, the real work of distribution begins. Sacks must be provided and kept in rotation. The exact quantity of flour required by a given Commune for a given period must be ascertained. Shipments by canal or rail or tram or wagon must be made to every Commune dependent upon the mill. Boats and cars and horses must be obtained and oil must be supplied for engines and fodder for horses. When the flour has reached the Local Committee it must be carefully distributed among the bakers in accordance with the needs of each. Baking involves yeast, and the maintenance of yeast factories, and the disposal of byproducts, and questions of hygiene and a dozen other minor matters. When the bread is baked it must be distributed to the population by any one of a dazes methods which guarantee an absolutely equitable distribution, each man, woman and child getting the varying ration to which he is entitled, paying for it if he can afford it, and getting it free if he can't. All this involves financial problems, and bookkeeping, and checking and inspection, all along the line; and the whole process to the tune of endless bickering with German authorities high and low, and endless discussions with a thousand Belgian committees.

Now, if you have digested that, you have some idea of what it means to supply a nation with bread. But that is only one item among many. Lard, rice, milk, clothing, etc., etc.: each involves its own special series of problems.

But "relief in Belgium" meant even more than this. By the middle of April 1917 nearly 5 million people in Belgium and northern France were destitute. Using the CRB's gifts from abroad and the profits from its own food sales to the well-to-do, the Comité National financed a vast and growing web of benevolence, including more than 2,700 local charitable committees as well as various other more specialized institutions. All in all, Hoover calculated that more than half the entire population was receiving some kind of assistance in the spring of 1917, including at least 2,700,000 who were helped by the communal charitable committee.

One object of special solicitude was the young. It was our task and the Belgians', Hoover wrote later, "to maintain the laughter of the children, not to dry their tears." Thanks to the CRB's external fund raising and food imports, and the dedicated zeal of Belgian volunteers, the challenge was impressively met. By early 1917 (to cite but one example) three-fourths of Belgium's children were receiving daily hot lunches at canteens established especially for this purpose.

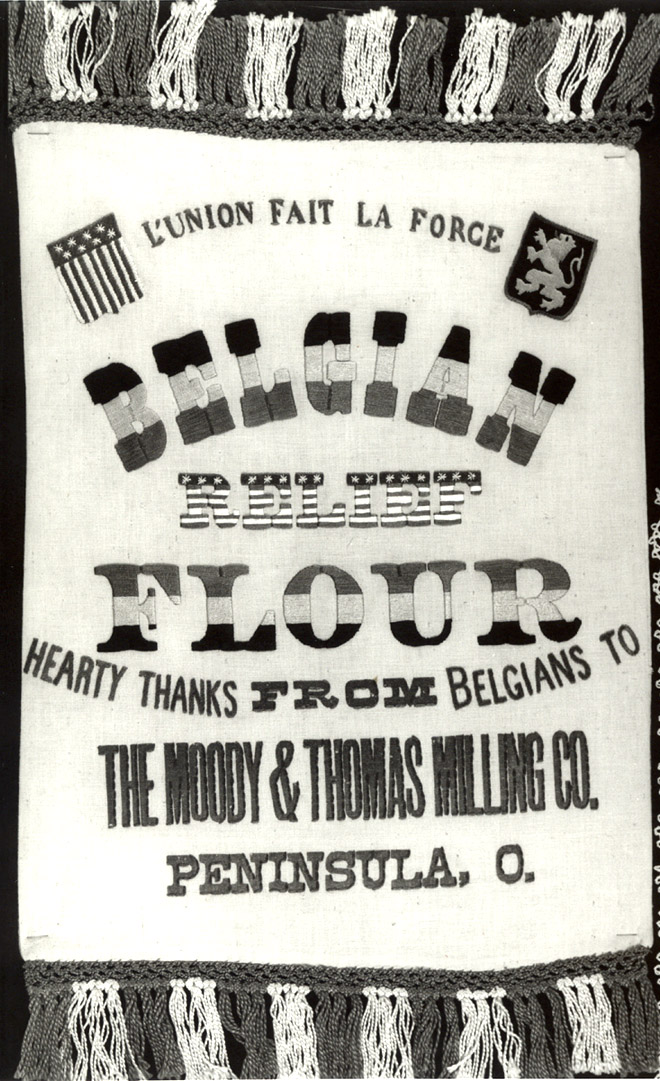

Another particular concern to Hoover was the plight of Belgium's renowned lace workers. Deprived of essential raw material by the invasion and subsequent blockade, a workforce of forty thousand women faced destitution, long-term idleness, and possible attenuation of their skills until Hoover and his associates stepped in. The CRB arranged to import needed thread for the lacemakers and to sell some of their finished products abroad. It also helped committees make advances to the women for their unsold production, such money to be recovered from the export of accumulated merchandise after the war. In these ways an entire industry was kept alive and thousands of skilled women self-supporting. The sale of the exquisite lace in England and the United States also no doubt helped to sharpen "the club of public opinion" that Hoover wielded in behalf of Belgium's cause.

No enterprise so massive, so multifaceted, so exposed to the passions of war, could hope to function undisturbed. This is the second feature of Hoover's relief experience that impresses the biographer: the unremitting pressures and troubles that beset him at every turn. From the day of its inception, the CRB had to cope with critics in the various belligerent governments who were convinced that its work was enhancing the military strength of one side or the other. Scarcely a month went by that did not witness some challenge to the precarious existence of the commission. Time and again Hoover was immersed in exhausting negotiations in an endless race against famine and malnutrition. Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, Lloyd George, the British Admiralty, the German high command: all at one time or another opposed him—and felt the sting of his relentless entreaties. At times, too, he had furious disagreements with his Belgian counterpart Emile Francqui, a man, like himself, of great ability and formidable force of personality. Let no one think that humanitarian relief, because of its noble and generous purpose, was exempt from political intrigue, personal ambition, and diplomatic rivalry. It was not.

Sometimes, weary from incessant conflicts with one or another belligerent power, Hoover contemplated resigning. "Were it not for the haunting picture in one's mind of all the long line of people standing outside the relief stations in Belgium," he wrote early in the war, "I would have thrown over the position long since." Ofttimes, too, he threatened to resign—the better to obtain his objectives. But Hoover did not quit. When the chips were down, it was his critics who yielded, recognizing his indispensability and growing stature and the risk of angering American public opinion that he had so skillfully mobilized.

Third, I continue to be impressed—as were so many observers at the time—by the energy, resourcefulness, and public relations acumen of the man at the apex of the CRB. While the relief commission had many volunteers—all, like Hoover, working without pay—and while Hoover himself emphasized the value of organization, his loyal subordinates knew that one man dominated their endeavors: the man they called "the Chief."

What kind of person was he? Here is Edward Eyre Hunt's description of him in the Belgian relief period:

In appearance he is astonishingly youthful, smooth-shaven, dark haired, with cool, watchful eyes, clear brow, straight nose, and firm, even mouth. His chin is round and hard.

One might not mark him in a crowd. There is nothing theatrical or picturesque in his looks or bearing. . . . At work he seems passive and receptive. He stands still or sits still when he talks, perhaps jingling coins in his pocket or playing with a pencil. His repertory of gestures is small. He can be so silent that it hurts.

Being an American he sometimes acts first and explains afterwards. But his explanations, like his actions, are direct and self-sufficient.

To Ambassador Walter Hines Page, life was "worth more . . . for knowing Hoover. But for him Belgium would now be starved. . . . He's a simple, modest, energetic little man who began his career in California and will end it in Heaven; and he doesn't want anybody's thanks."

Hoover's ability to concentrate on the relief problems at hand was almost legendary. Joseph C. Green later described an encounter he had with "the Chief" in the Brussels office of the CRB:

. . . I found Mr. Hoover standing with his back to the wall, gazing fixedly at a spot on the floor five or six feet in front of me.

I went over, said good morning, and was about to proffer my hand in the Belgian fashion when I became aware that he was absolutely unconscious of my presence. I stood about awkwardly for a few minutes fill he came to with a start, and recognized me with a nod. This extreme absorption in the business of the moment is one of Mr. Hoover's chief characteristics. Belgians, with their more elaborate code of good manners, find it difficult to understand him.

Sometimes Hoover's ability to concentrate had amusing aspects. Hugh Gibson, an American diplomat, told Green one day of the time

that Mr. Hoover once came to the Legation to see him on business. During the entire conversation he paced the floor in the little salon upstairs. One of his parings led him to the door, and he walked out. Gibson thought that he was going to continue his walking up and down in the hall, and his first intimation that the interview was terminated was the sound of footsteps hurrying downstairs. Gibson ran after him and just reached the outside door in time to shout a hurried goodbye.

When the United States entered the European conflict in 1917, Hoover returned home to head a new wartime agency, the United States Food Administration. But the relief commission that brought him fame continued to function, although in a reorganized form necessitated by the end of American neutrality. Throughout the war the CRB and Comité National indefatigably fed more than nine million people a day in Belgium and northern France. And when the commission finally closed its accounts, it found that it had spent nearly a billion dollars. It had sustained the health and morale of the Belgian people. It had made Herbert Hoover an international symbol of practical idealism, and it had launched him on what he later called "the slippery road of public life."

Hoover was not a man to covet what he called "European decorations." Moreover, once he became an official of the United States government he could not accept a title of nobility. In August 1918, therefore, when Hoover visited the tiny portion of Belgium not under German control, King Albert, on petition of his ministers, presented his American guest a specially created, unique title: "Ami de la nation belge," Friend of the Belgian Nation. By royal directive only Hoover would ever hold this title of esteem.

Hoover's association with Belgium did not terminate with the end of World War I. At point he could easily have retired from the scene; most men no doubt would have done so. But even before the cessation of hostilities he was thinking ahead to the reconstruction of the strife-torn land whose history had intersected so fatefully with his own. As early as 1916 he suggested to the exiled Belgian minister of finance that the CRB's excess funds at the end of the war be used to establish a foundation "for the stimulation of scientific and industrial research." In 1918 Hoover confided to the American minister to Belgium, Brand Whitlock:

As to the question of re-building in Belgium and Northern France,—it is the one job that I would like to have. I believe that it contains usefulness and sentiment beyond any other occupation after this War is ended, and there is nothing that would appeal to me so much as to join with you in a mission of this kind. . . .

In 1920, after various negotiations, Hoover's dreams achieved practical fruition. Upon liquidating, the CRB had a surplus of over $35 million. Of this sum it distributed more than $18 million in outright gifts to the Universities of Brussels, Ghent, Liege, Louvain, and other educational institutions. The remainder of the money was divided between two foundations created that year: the CRB Educational Foundation in the United States, and the Fondation Universitaire in Belgium.

Through this device Hoover and his wartime associates forged enduring bonds of Belgian-American cultural exchange, bonds that persist to this day. During the 1920s, for instance, Hoover's foundation granted over $1,600,000 for the rebuilding of the University of Louvain, so terribly ravaged during the German occupation. Thus was born in the tragedy of World War I an empire of philanthropy with which Hoover was identified for the rest of his life.

Finally—and this is the fourth theme to which I call your attention—the creation of the Commission for Relief in Belgium turned out to be more than a passing episode in a great war—and more than a springboard to one man's political career. Hoover's endeavor was in fact a pioneering effort in global altruism—in his own words, "an American epic" that in some ways was the prototype of much that followed in this bloody century. In 1916 Lord Eustace Percy of the British Foreign Office described Hoover as "the advance guard and symbol of the sense of responsibility of the American people towards Europe." A few months later the New Republic echoed this assertion, acclaiming the CRB as "an outpost of the Republic" whose continued success was of the highest national priority. Hoover and his colleagues, declared the journal, had "created an American obligation in Europe." To the New York Times in early 1917, Hoover's administration of the CRB ranked as "perhaps the most splendid American achievement of the last two years."

In more recent times the world has grown accustomed to American action to save lives and restore the fractured economies of far-off lands. Indeed, today such involvement is almost universally taken for granted. One reason for this expectation, one reason for its acceptance—although few today know it—is the institution created nearly seventy-five years ago by Herbert Hoover.

For Hoover, also, the Belgian experience was but a prologue. In the years 1917 to 1921, he as well as his country moved even more prominently onto the international stage. No longer just the almoner of Belgium, he became (in General Pershing's words) "the food regulator for the world"—or, as one admirer put it, a "Napoleon of mercy." It has been said that Hoover was responsible for saving more lives than any other person in history. The story of that achievement during the remainder and aftermath of World War I will be a principal focus of the next volume of my biography.

Sixty years ago this fall, while Hoover was seeking the office of President, a certain mediocrity was running for city council in Augusta, Georgia. The candidate apparently knew his limitations, for he announced in his campaign advertisements, "I know I'm not much, but why vote for less?" Without discussing Hoover's later political odyssey, I hope I have said enough here to suggest why his contemporaries came to feel that with him they did not, so to speak, have to "vote for less," and how it was possible for him to become President of the United States without ever having held an elective office.

Why did he do it? An autobiographical statement that he composed sometime during World War I provides a clue:

There is little importance to men's lives except the accomplishments they leave to posterity. What a man accomplishes is of many categories and of many points of view; moral influence, example, leadership in thought and inspiration are difficult to measure, to prove or to treasure . . . and the proportion of success to be attributed to their effort is always indeterminate. In the origination or administration of tangible institutions or constructive works men's parts can be more certainly defined. When all is said and done accomplishment is all that counts.

During his lifetime Hoover created and administered many "tangible institutions," the most remarkable of which was the Commission for Relief in Belgium. He also left behind a panoply of achievements long obscured by the bitter memory of the Great Depression. When Hoover died in 1964 at the age of ninety, he had spent fifty years—a half century—in one form or another of public service. It was a record that in sheer scope and duration may be without parallel in American history.

A life like that requires not pages but volumes to measure.

George H. Nash received his doctorate from Harvard University. He is the author of several books, including The Life of Herbert Hoover: The Humanitarian, 1914–1917, the second volume in a projected multivolume biography of our thirty-first President. This essay was first presented as a lecture at the National Archives on November 3, 1988.