How Roosevelt Attacked Japan at Pearl Harbor

Myth Masquerading as History

Fall 1996, Vol. 28, No. 3

By R.J.C. Butow

© 1996 by R.J.C. Butow

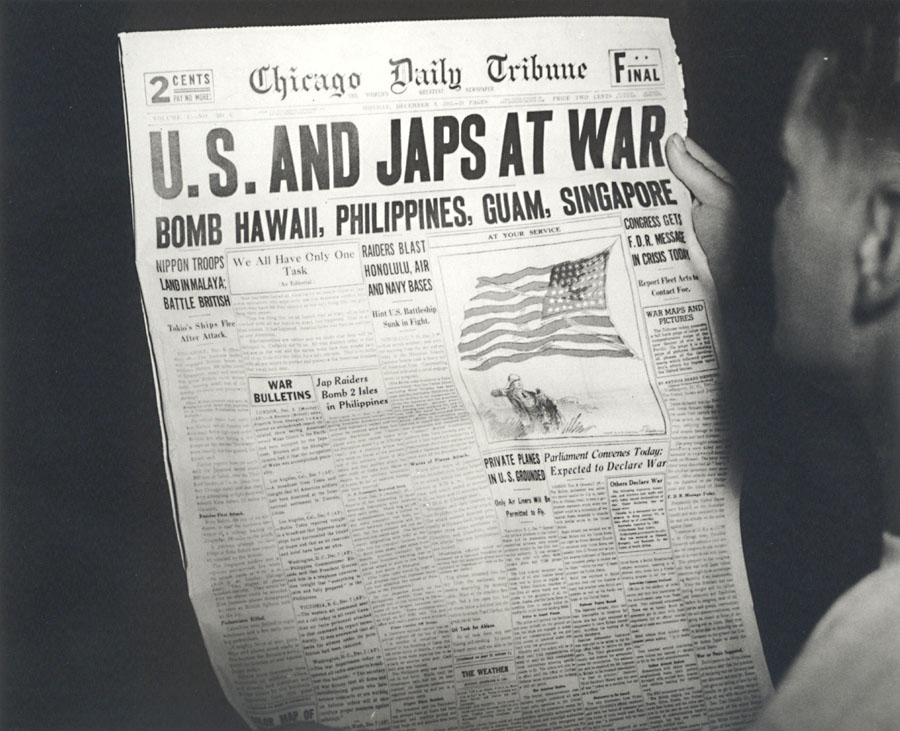

December 7, 1941, began as a typical Sunday for millions of Americans, but suddenly everything changed, irrevocably, in ways they would remember for the rest of their lives. As the news flashed from coast to coast, the bombing of Pearl Harbor mushroomed into a national disaster. People could scarcely believe the reports pouring out of their radios. How could it have happened? Who was to blame? What could be done to guard against surprise attacks in the future?

There were no easy answers, no quickly forged consensus. In these circumstances, perhaps it was inevitable that certain critics of the President would emerge as "Pearl Harbor revisionists," eager to accuse Franklin D. Roosevelt of having misled the public in regard to the coming of the war in the Pacific. These detractors paid little attention to Japanese military intrusions in East Asia in the decade prior to Japan's attack on the United States. They ignored the historical background that is needed for an understanding of what happened in 1941. Instead of carefully mapping their way through the records of the period, they hacked out a trail of Machiavellian conspiracy that twisted and turned and switched back on itself until it eventually led to the White House.

There is nothing wrong with updating earlier interpretations or with correcting erroneous judgments. Historians do this routinely. As new material comes to light, previously accepted explanations must be revised. Normally this is done only when incontrovertible evidence is at hand—evidence so unassailable that the historical community can embrace the reinterpretation with confidence.

Honestly held differences of opinion can easily arise out of conflicting interpretations of what happened in the past, even when everyone accepts the same set of facts. This form of debate is one of the most important mechanisms by which historians eventually arrive at tenable conclusions. What is disturbing about the Pearl Harbor revisionists, however, is their tendency to disregard the rules of scholarship and to gloss over the complexities of the historical record. They are determined to spread the notion that Roosevelt goaded the Japanese government into attacking the United States at Pearl Harbor, thus making it possible for him to enter the European conflict through the "back door of the Far East." They therefore attribute Tokyo's decision for war to the allegedly arbitrary policies sanctioned by the President, especially the freezing of Japan's assets in July 1941 and the proposal for a settlement that Secretary of State Cordell Hull presented to the Japanese government in November.

Archival research does not support these contentions. The problem in 1941 was not that Roosevelt was relentlessly pushing Japan's leaders toward the brink; the problem was that he could not find a viable way to stop them from taking the plunge of their own accord. The Supreme Command in Tokyo had various goals in mind, not the least of which was a preemptive strike designed to capture the resources that abounded in Southeast Asia—resources and territory that might fall into the hands of Japan's competitive ally, Germany, if Hitler succeeded in conquering his enemies in Europe.

Roosevelt was forceful enough in the Atlantic to cause some observers to think that Hitler might take up the challenge in circumstances favorable to his own malevolent designs. In the Pacific, however, the President was prepared to be conciliatory. Over a period of months, he had resisted the tempting advice of several members of his cabinet who had urged him to adopt stringent measures. One of these activists, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, had been given additional responsibility as petroleum coordinator for national defense. A month before the Japanese government sent its troops into southern French Indochina in the summer of 1941, Ickes recommended to the President that shipments of oil to Japan be stopped immediately. In a brief reply that skated on the edge of sarcasm, FDR said, "Please let me know if this would continue to be your judgment if this were to tip the delicate scales and cause Japan to decide either to attack Russia or to attack the Dutch East Indies." 1

When Ickes argued the case, the President pressed his own point of view. He said that a knock-down, drag-out fight was taking place in Tokyo. Japan's leaders were trying to figure out which way to jump—whether to invade the Soviet Far East or the South Seas or whether to "sit on the fence and be more friendly with us." The decision was anyone's guess, "but, as you know," he told Ickes, "it is terribly important for the control of the Atlantic for us to keep peace in the Pacific. I simply have not got enough Navy to go round—and every little episode in the Pacific means fewer ships in the Atlantic." 2

Once Japanese troops began moving into southern Indochina, however, a new situation was created. 3 The President consequently changed his mind about the way to react. He first suggested that Japan join with the United States and other powers to treat Indochina as a neutralized country in the nature of a Far Eastern Switzerland (an idea to which Tokyo proved to be unresponsive); Roosevelt then sent a message in a language everyone could understand: Overnight, he froze all Japanese assets in the United States. 4 Although he did not reveal his intentions, his order was soon processed through lower levels of bureaucratic consultation into a full trade embargo, thus stopping the shipment of oil to Japan. 5

FDR had by now learned that a policy of forbearance toward the government in Tokyo, instead of having a salutary effect, simply resulted in ever-more aggressive behavior on the part of the Imperial Japanese Army. Only after this fact had been driven home with galling emphasis did the President move decisively. His executive order was not an arbitrary action taken without provocation. It was a long-delayed response to repeated Japanese policy initiatives that threatened the national interests and security concerns of the United States as perceived and defined by the American government.

The revisionists have always been drawn to items that appear to cast Roosevelt in an unfavorable light—for example, a few lines in Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson's diary for November 25, 1941. 6 The President is not quoted directly, but Stimson says that FDR "brought up the event that we were likely to be attacked perhaps next Monday [December 1], for the Japanese are notorious for making an attack without warning, and the question was what we should do. The question was how we should maneuver them into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves." 7

To understand this passage we need to know how the secretary of war managed to find time to keep a diary not only during a very busy period in his life but also in the proximity of a President who generally did not want cabinet officers, or anyone else for that matter, taking notes during their discussions with him. 8 Often, Stimson would simply have to rely on his memory, but whenever possible he would take selected papers home with him to help recall the day's activities. He would use a Dictaphone in the evening, or before departing for his office the following morning, to record what had transpired. His secretary would then transcribe the material, but Stimson apparently did not edit the typescript. 9 Anyone who uses this rich source will soon become aware of the problems it presents: awkward phrasing here and there, irreconcilable changes in tense, pronouns with ambiguous antecedents, and—most serious of all—elliptical passages that raise questions of interpretation.

In this instance, the revisionists have latched onto the word "maneuver," using it to portray Roosevelt as a man bent on luring Japan into war. Implicit in their accusation is the idea that the Japanese government was a helpless victim blindly stumbling into a trap.

This is not credible. The decision makers in Tokyo were on the verge of resorting to force—a policy of choice they had formulated on their own. They were not ensnared by Roosevelt or anyone else.

In dictating his entry for November 25, Stimson may subconsciously have put some of his own ideas, and perhaps his own words, into the President's mouth. 10 Even if the secretary of war paraphrased FDR correctly, what does the entry mean? A speculative answer is that Roosevelt may have been thinking along these lines: Japan's leaders seem to be on the point of going to war somewhere in Southeast Asia. Our hands are tied until their army and navy commit the first act. The responsibility for resorting to hostilities must rest on Japan's armed forces, where it properly belongs. At the same time, the United States must minimize the risk entailed in sitting back and waiting for something to happen.

In his diary Stimson remarked, "It was a difficult proposition." 11

Operation "Magic" was concurrently producing translations of intercepted Japanese diplomatic and consular messages that caused growing concern on the part of the few officials who had access to their contents, but the problem was greater than they realized. We now know that in 1941 this top secret army-navy project was burdened by operating procedures and personnel shortages that prevented it from achieving its potential. This was the case not only in the analysis but also in the dissemination of the extraordinary information "Magic" was plucking from the air waves. 12

The emphasis that was placed on the maintenance of secrecy is as understandable now as it was then, but in some instances security concerns stood in the way of maximizing the benefits that could have been derived from the revelations the intercepts contained. Human error—not conspiracy—lay at the base of this problem.

Badly needed, but absent from the scene, was a "Magic" coordinator—an intelligence czar empowered by the President to reassess intercepts on a regular basis and to provide continuity of interpretation from week to week. Although Roosevelt personally had to avoid getting bogged down in details, he should have been briefed more fully in 1941 than the system in place during that year allowed. 13

"Magic" provided intelligence of value to the State Department in formulating policy, but the military and naval threat to American territory posed by Japan could not be determined with any degree of certainty. Messages between the Foreign Office in Tokyo and Japanese embassies in various parts of the world in 1941 dealt with foreign relations, not with strategy and tactics. Despite some claims to the contrary, none of the diplomatic messages that were intercepted and translated prior to December 7 ever pointed to Hawaii as a target that might be imminently hit.

Confusion has arisen in this regard because intercepts obtained from consular traffic revealed that Tokyo was definitely interested in ship movements in and out of Pearl Harbor, an interest that "Magic" had begun monitoring a year before the attack took place. Drawing correct conclusions was difficult because Japanese espionage was by no means limited to the Hawaiian Islands or to ship movements. Tokyo's appetite for useful data, including information about military installations, covered other vital areas: the Panama Canal, the Philippines, Southeast Asia (including the Dutch East Indies), and major West Coast ports in the United States and Canada. Even American warships anchored in Guantanamo Bay on the southeast coast of Cuba, in July 1941, merited a report to Tokyo from a Japanese source in Havana. 14

Far more important than odd items of this nature was Telegram No. 83 from the authorities in Tokyo to an espionage agent in Honolulu. It was sent on September 24 but was not translated by "Magic" until October 9. The agent was told to divide the waters of Pearl Harbor into five areas, each of which was precisely defined. Henceforth he was to report on the types and classes of U.S. Navy ships that were anchored or moored in each of these areas. "If possible," the message read, "we would like [you to inform us] when there are two or more vessels alongside the same wharf."

In practical terms, these instructions meant that Tokyo was placing a bombing grid over the target. 15

Two officers in Washington were troubled by Telegram No. 83, but their separate assessments were turned aside by others. The Japanese message was seen as an effort to encourage Tokyo's agent to condense his reports, to focus on essentials, to economize on wording. No. 83 was explained away as an example of the attention the Japanese always paid to details—it was evidence of the "nicety" of their intelligence operation. No one saw any reason to send warnings to Pearl Harbor. If war came, the Pacific Fleet would put to sea in plenty of time to cope with the Japanese threat (or so everyone thought). 16

After the raid, the implications that had been missed earlier seemed to jump out at every analyst who read Telegram No. 83 and others like it, but in 1941 insurmountable doubt ate away at sound judgment. Today we can study the intercepts both serially and selectively, in the luxury of freedom from the pressures that existed at the time, and with the clarity of vision that the incandescent light of hindsight provides. We can readily see that the espionage exchanges between the Foreign Office in Tokyo and Japan's consulate general in Honolulu contained important clues that were not detected by key military and naval personnel in the War Plans and Intelligence Divisions in Washington. As a consequence, the hostile intentions that were implicit in these telegrams were not conveyed to commanders in the field who should have been alerted immediately. 17

Several messages that might have saved the day, at the very last moment, ended up falling "between the cracks" in the processing system, which could not always keep up with the flow of intercepts. Two inquiries from Tokyo during the first week of December, for example, produced a reply from Honolulu that "Magic" intercepted on December 6. "At the present time," the agent reported, "there are no signs of barrage balloon equipment [at Pearl Harbor]. . . . In my opinion the battleships do not have torpedo nets." 18

This report also contained a dead-giveaway sentence: "I imagine that in all probability there is considerable opportunity left to take advantage for a surprise attack against these places." The phrase "these places" included Pearl Harbor, Hickam Field, and Ford Island—all of which were blasted the very next morning. 19

Anyone would think that an intercept of this nature would have awakened Washington and triggered warnings to Pearl Harbor. The problem was that no one saw it in time. It was not translated until December 8, the day after the attack. This was also the fate that befell still another telegram that was sent to Tokyo on December 6 by the Imperial Japanese Navy spy in Honolulu: "It appears that no air reconnaissance is being conducted by the fleet air arm." This message might have opened some eyes on December 6 or 7, but the "Magic" translation is dated "12/8/41." 20

Translation delays should not be attributed to skulduggery or incompetence. At the processing level, Operation "Magic" was understaffed and overworked; diplomatic messages in top-secret "Purple," the most difficult of the machine ciphers that were used in these transmissions, had a higher priority than consular messages encrypted in systems such as J-19 and PA-K2; the volume of deciphered intercepts grew from a trickle in 1940 to a flood in 1941; expert translators with "top secret" security clearances were so scarce they could have been described as an endangered species. The wonder is that the men and women of "Magic" performed as well as they did in these circumstances. 21

By late November 1941 events were moving at a rapid pace. Even before Stimson dictated his controversial entry for November 25, Secretary Hull had learned, from a "Magic" intercept, that the foreign minister in Tokyo had informed Japan's representatives in Washington that diplomatic efforts to reach what he called "the solution we desire" must be concluded by November 29. They were told: "[This] deadline absolutely cannot be changed." The wording of the very next sentence echoed ominously: "After that, things are automatically going to happened." 22

What things and where? This was the unanswerable question in Washington.

In a message to Winston Churchill, the President revealed that he was aware of the danger from Japan: "We must all be prepared for real trouble, possibly soon." 23

Intelligence derived from sources other than "Magic" reinforced the idea that war was near. The Japanese were sending a large expedition to sea from Shanghai in occupied China. This armada was heading toward Indochina, but American policymakers were in the dark concerning its ultimate destination. 24 This was the atmosphere in which Hull handed his now famous note of November 26 to Ambassador Kichisaburō Nomura and Special Envoy Saburō Kurusu. 25

Why did Japan's leaders reject the American offer? Did they do so because the note was an "ultimatum" (as the revisionists claim) or for other reasons? The evidence suggests that the terms outlined by Hull were unacceptable to the decision makers in Tokyo because they wanted a diplomatic capitulation by the United States. If Washington did not oblige, they were prepared to resort to force. The commander in chief of Japan's Combined Fleet had already issued top secret operational orders for the attack on Pearl Harbor. He had done this three weeks before the American note reached the Foreign Office. 26 The ships composing the strike force had sailed for Oahu before the Japanese government examined Hull's proposal. 27 In effect, Japan's decision for war had already been made.

Even before the fighting started, Tokyo sought to undermine the Hull note, dismissing it as a "humiliating proposal" that the government could not possibly accept. 28 The facts fly in the face of this assertion, but the Pearl Harbor revisionists have glibly repeated it for years.

The note was tendered on a "Tentative and Without Commitment" basis; it outlined reciprocal undertakings and offered room to maneuver. On the critical issue of Japanese troops on the continent of Asia, for instance, Hull stipulated a withdrawal of "all military, naval, air and police forces from China and Indochina." He did not say when this had to be done; this was negotiable. 29 There was no mention whatsoever of Manchuria—the Japanese presence there was also negotiable. 30 Hull did not call for a concrete response within a specified deadline; therefore, his note was not an "ultimatum."

On November 27, the President told Nomura and Kurusu: "We are prepared . . . to be patient if Japan's courses of action permit . . . such an attitude on our part. We still have hope . . . [but] . . . [the United States] cannot bring about any substantial relaxation in its economic restrictions unless Japan gives this country some clear manifestation of peaceful intent. If that occurs, we can also take some steps of a concrete character designed to improve the general situation." 31

Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall and Chief of Naval Operations Harold R. Stark were frankly opposed to doing anything that might precipitate war. They were eager to buy time to develop enough strength to cope effectively with whatever action the Japanese government might take in the southwestern Pacific—the area where the Imperial Army and Navy were most likely to strike. Until the Philippines could be reinforced more fully, General Marshall and Admiral Stark recommended that military counteraction against Japan be considered only if the Japanese attacked or directly threatened American, British, or Dutch territory in Southeast Asia. 32

When a joint committee of the Congress asked Hull, in 1945, to comment on an assertion to the effect that his note of November 26, 1941, had pushed the button that started the war, the anger felt by the former secretary of state was evident in his reply. "If I could express myself as I would like," he said, "I would want all of you religious minded people to retire [from the room]." 33

At the White House on Wednesday, December 3, 1941, FDR was alert to what was happening in East Asia, but he was not entirely correct in his assessment of the situation. He erroneously thought "he had the Japanese running around like a lot of wet hens" because he had asked them why they were pouring military forces into Indochina. He came much closer to the truth when he said: "I think the Japanese are doing everything they can to stall until they are ready." 34

The next day, Roosevelt's naval aide called his attention to a "Magic" intercept that ordered the Japanese embassy to burn most of its "telegraphic codes," to destroy one of the two machines it used to encrypt and decrypt messages, and to dispose of all secret documents. This meant that Japan was on the point of kicking over the traces—of opting for war. FDR wondered aloud when this would occur. No one knew, but the President's naval aide offered a wide-open guess: "Most any time," he said. 35

Secretary of War Stimson remembered Saturday, December 6, as a day of foreboding. As the morning wore on (his diary reads), "the news got worse and worse and the atmosphere indicated that something was going to happen." 36

The Japanese expedition that had departed from Shanghai was now reported to be steaming in the direction of the Kra Isthmus in the north-central portion of the Malay Peninsula. A week earlier, during a meeting with his most important civil and military advisers, FDR himself had pointed to the isthmus as the place where the Japanese might begin an offensive. 37

No one had forgotten about the potential threat to Pearl Harbor, the Panama Canal, or any other base close to home, but the indications were that the Imperial Army and Navy were going to break out somewhere in the distant western Pacific, an area rich in the resources they were eager to obtain.

This was the context in which the President reacted to the first thirteen parts of a fourteen-part message from the foreign minister in Tokyo to Ambassador Nomura in Washington; it arrived in the form of a "Memorandum" that would soon prove to be Japan's final note to the United States. The incomplete intercept was brought to FDR around 9:30 Saturday evening, December 6, as he was sitting in the oval room that served as his study on the second floor of the White House, talking with his friend and adviser Harry Hopkins. The text of Japan's "Memorandum," Telegram No. 902, had been sent from Tokyo in English, encrypted in "Purple." The very lengthy note was largely an attempt to justify Japan's Far Eastern policy by vigorously denouncing the attitude of the United States. Only one sentence in Part 13 hinted at what might be said in the still-missing final segment of the telegram. The Japanese government, this sentence declared, "cannot accept the [Hull] proposal [of November 26] as a basis of negotiation." 38

This announcement, together with the negative tenor of the "Memorandum" as a whole, allowed FDR to put two and two together. After reading through the document, the President turned to Hopkins and said, in substance: This . . . means . . . war.

The exact words Roosevelt used will never be known, because the naval officer who had brought the message to the oval study, and who was the only surviving witness after the war to what had transpired there, could not remember, later, precisely what had been said. He had been in the room the entire time FDR and Hopkins discussed the intercept, but he was not asked, until 1946, to relate what he had seen and heard that evening. The President may well have had war on his mind—not an attack on Pearl Harbor, but a Japanese invasion of Southeast Asia. 39

Around ten o'clock the next morning, December 7, the intercepted text of the missing segment of Telegram No. 902 was delivered to FDR. Part 14 accused the American government of having used Nomura's negotiations with Hull "to obstruct Japan's efforts toward the establishment of peace through the creation of a New Order in East Asia." As a consequence, the Japanese government had come to the conclusion that an agreement could not be reached with the United States "through further negotiations." 40

This was all that Part 14 said. It did not declare war. It did not sever diplomatic relations or reserve freedom of action. On the surface, it amounted to nothing more than a suspension of the Hull-Nomura conversations. 41 A few hours after Roosevelt read the intercept, the hidden meaning of Part 14 was unveiled at Pearl Harbor.

The President's death in the spring of 1945 denied us the opportunity we otherwise might have had in the early postwar period to hear him defend himself against revisionist accusations. Over the years, others have addressed the subject, expressing various views. 42 Some historians have offered eloquent arguments on Roosevelt's behalf, but the revisionists—thwarted in one area of the ongoing debate—have popped up somewhere else, peddling hearsay, rumor, insinuation, and distortion. In the judgment of their critics, they have emerged as sleight-of-hand conjurers adept at creating illusions. In their persistent but skewed accounts, substituting fiction for fact, they have relied heavily on innuendo, a device that is quintessentially inexhaustible. Time after time, they have exhibited what FDR called, in a different context, "merry-go-round minds." Persons with this affliction, he said, "start at a given point, follow a circular track, move with great rapidity and keep coming back time after time to the same point." 43

What standard of proof would satisfy historians at large in regard to the sinister role the revisionists allege Roosevelt played in American relations with Japan? The legal profession provides the best guidance. The standard of proof in any ordinary civil trial in the United States is achieved by "a preponderance of the evidence." In certain civil actions, another standard is employed. Here the evidence must be "clear, cogent, and convincing." In a criminal trial, an even higher standard is required. To convict an accused person, jurors must be persuaded "beyond a reasonable doubt" that the defendant is guilty of the crime as charged. 44

The arguments presented by the Pearl Harbor revisionists fail to meet any of these standards and should therefore be rejected. If anything new ever comes to light, of whatever nature, historians will examine the material meticulously. If it proves to be authentic, they will make whatever adjustments are needed to update their record of the past.

If FDR had known what Japan's naval planners had up their sleeves, he could easily have arranged a surprise of his own for their task force, stealthily bearing in on Oahu. He could have made sure that the Pacific Fleet would be far out to sea, ready to take whatever countermeasures it was capable of devising at that critical moment.

Revisionists often ignore salient facts. The bombing of Pearl Harbor, for instance, was merely one phase of the massive offensive the Imperial Army and Navy concurrently launched throughout Southeast Asia and against various American outposts in the Pacific. The Japanese attack on the Philippines alone would have resulted in a congressional declaration of war. Even if no American territory other than the islands of Guam and Wake had been hit, the United States would have become a belligerent. The revisionists shrewdly focus on Pearl Harbor, however, because what happened there, despite the passage of years, still has the power to capture our attention.

According to Harry Hopkins, FDR had "really thought" that the Japanese would try to avoid a conflict with the United States—they would not move against either the Philippines or Hawaii but would push more deeply into China or seize Thailand, French Indochina, and possibly the Malay Straits. Roosevelt also thought that Japan would strike at the Soviet Union at an opportune moment. 45

While the President and his advisers had worried over maps of Southeast Asia, the Imperial Japanese Navy had stolen in on the one spot everyone assumed was secure. For Roosevelt personally, December 7 was exactly what he chose to call it publicly—a date that would live in infamy. Nothing else, except perhaps a crippling of the Panama Canal, could have affected him so deeply. Gliding by in a wheelchair on his way to the Oval Office soon after he had heard of the attack, FDR looked like a man in a fighting mood. In the words of Secret Service Agent Mike Reilly: "His chin stuck out about two feet in front of his knees and he was the maddest Dutchman I—or anybody—ever saw." 46

The passage of time has confirmed what every major figure in Washington understood in 1941: The President could see the broad outlines of what was occurring in the Far East—he realized that the leaders of the Imperial Army and Navy were positioning their forces to expand the theater of operations. Japanese troops were already fighting a war in China; now they were going to invade Southeast Asia.

Roosevelt had no way of learning precisely what Japan's decision makers were going to do about their unresolved quarrel with the United States. "Magic" translations dealt with diplomatic matters and espionage activities, not with the secrets of the Japanese armed forces. Despite mind-crunching efforts, American cryptanalysts were unable to achieve meaningful results, in 1941, in breaking into JN-25, a major Japanese naval code and cipher system. Operational intelligence at the command level of Japanese naval activity was consequently unavailable to the President and U.S. flag officers prior to Pearl Harbor. 47

FDR simply did not know that the Imperial Navy, departing from an earlier war plan that called for engagement of the enemy close to Japanese home waters, had now chosen the Pacific Fleet in far-off Hawaii as one of its initial targets. 48

The failure of diplomacy to defuse the Far Eastern crisis proved to be a tragedy for all concerned. In the course of a single decade—from the Manchurian Incident of 1931 onward—more than half a century of amicable relations had dissolved into bitterness, culminating in the irrational violence of war. The American people were greatly angered by the assault that had been made upon them, and by the toll of casualties. In their wrath they innocently vowed never to let anything like that happen again. "Remember Pearl Harbor!" was on everyone's lips.

In Japan there was elation over the initial successes achieved by the Imperial Army and Navy, bringing Southeast Asia under their control. Highly regimented and closely watched for any sign of "dangerous thoughts," the masses were swept into the conflict carrying with them the baggage of many propaganda-induced delusions.

Out of the disaster on Oahu a revisionist myth emerged that has been masquerading as "history" ever since. In its most extreme form it invites us to stand on our heads and look at everything upside down. It asks us to believe that on December 7, 1941, Franklin D. Roosevelt attacked Japan at Pearl Harbor. As we approach the fifty-fifth anniversary of that unforgettable Sunday, surely the time has come to lay this flagrant idea to rest.

Notes

1 Harold Ickes to FDR, June 23, 1941, and Roosevelt's reply of the same date, The Secret Diary of Harold L. Ickes, vol. 3, The Lowering Clouds, 1939–1941 (1954), pp. 557–558. For the context of this exchange, see pp. 537–539, 548–568.

2 Ibid., pp. 552–568; Ickes to FDR, June 25, 1941, Folder: F.D.R.: His Personal Letters, Dept. of Interior, Roosevelt Family Papers Donated by the Children, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY; F.D.R.: His Personal Letters (3 vols. in 4 books), ed. Elliott Roosevelt et al., vol. 3, book 2 (1950), pp. 1173–1174.

3 On July 16, 1941, the American ambassador at Vichy reported that Adm. Jean François Darlan had told him: "We have just learned that the Japanese are going to occupy bases in Indochina in the immediate future,—within the next week. There has been no Japanese ultimatum; they speak courteously of jointly occupying Indochina with us for common defense but it amounts to a move by force. They pretend that their mobilization is for a move to the north but I think it is for a move to the south and toward Singapore. We will make a symbolic defense, but we do not have the means to put up a fight. . . .I have been warned not to let you know in order to avoid any possible preventive move on your part." U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1941, vol. 5, The Far East (1956), pp. 213–214 (hereinafter cited as FRUS).

4 FDR tendered his neutralization proposal orally during a conversation with the Japanese ambassador on July 24. R.J.C. Butow, The John Doe Associates: Backdoor Diplomacy for Peace, 1941 (1974), pp. 230–231, 236–238, 415, 417. The recently opened papers of Sumner Welles contain a copy of an August 2, 1941, memorandum describing a conversation in which the Japanese ambassador attempted to explain why his government had as yet made no reply to the President's proposal. Folder: Japan, 1938–1941, box 165, Europe Files, Welles Papers, FDR Library. (This item can also be found in FRUS 1941, 4: 360–361.

A White House press release, handed to reporters on Friday, July 25, at Poughkeepsie, NY (near the President's home at Hyde Park), announced the issuance of Executive Order No. 8832, signed July 26, 1941, freezing Japanese assets in the United States. FRUS: Japan, 1931–1941, vol. 2 (1943), pp. 266–267.

5 See Herbert Feis, The Road to Pearl Harbor: The Coming of the War Between the United States and Japan (1950), pp. 142–144, 205–208, 227–250; William L. Langer and S. Everett Gleason, The Undeclared War, 1940–1941 (1953), pp. 645–654; Irvine H. Anderson, Jr., The Standard-Vacuum Oil Company and United States East Asian Policy, 1933–1941 (1975), pp. 174–180, 189–192, and passim; Jonathan G. Utley, Going to War with Japan, 1937–1941 (1985), pp. 151–156; Michael A. Barnhart, Japan Prepares for Total War: The Search for Economic Security, 1919–1941 (1987), pp. 215–219, 225–232, and passim (p. 231 n. 46 mentions a difference in interpretation between Barnhart and Utley); Waldo Heinrichs, Threshold of War: Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Entry into World War II (1988), pp. 132–136. Reactions to the freezing of assets are summarized in Butow, Tojo and the Coming of the War (1961, reprint 1969), pp. 223–227, 242–243, 245, and in John Doe Associates, pp. 232, 239–242, 270.

A July 31, 1941, memorandum to the President, written by Acting Secretary of State Sumner Welles, who delivered it in person that same day, throws light on the emergence of policy at that time. Folder: Japan, 1938–1941, box 165, Europe Files, Welles Papers, FDR Library. The memorandum, which FDR approved, is printed in FRUS 1941, 4: 846–848.

6 The entry includes a brief account of a meeting with the President that lasted nearly an hour and a half (with Hull, Knox, Marshall, and Stark also present). Henry Lewis Stimson Diaries, Nov. 25, 1941, Yale University Library, Manuscripts and Archives, microfilm edition (hereinafter Stimson Diaries), roll 7, vol. 36, pp. 48–49; Feis, Road to Pearl Harbor, pp. 314–315; Langer and Gleason, Undeclared War, pp. 885–887; Richard N. Current, "How Stimson Meant to 'Maneuver' the Japanese," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 40 (June 1953): 67–74; Robert H. Ferrell, "Pearl Harbor and the Revisionists," The Historian 17 (Spring 1955), p. 219 n. 7; Roberta Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision (1962), pp. 239–241; Butow, Tojo and the Coming of the War, p. 336 n. 40.

7 On August 2, 1941, Hull had foreseen the need to "maneuver the situation" in favor of the United States (FRUS 1941, 4: 348–349). In mid-October Stimson had noted: "The Japanese Navy is beginning to talk almost as radically as the Japanese Army, and so we face the delicate question of the diplomatic fencing to be done so as to be sure that Japan was put in the wrong and made the first bad move—overt move." Langer and Gleason, Undeclared War, p. 730; Stimson Diaries, Oct. 16, 1941, roll 7, vol. 35, pp. 136–137.

8 While talking with Henry Morgenthau, Jr., on October 3, 1939, FDR said that he disliked note-takers. He referred to the "notes on Lincoln's Cabinet" kept by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, whom he described as a friendly source. "If some other member . . . who was not friendly had kept [such notes], just see what a distorted viewpoint you would get." Oct. 3, 1939, Presidential Diaries, 2: 319, Morgenthau Papers, FDR Library. The irony here is that Roosevelt was talking to a man—one of several in FDR's official family—who kept voluminous journals describing everything that was happening behind the scenes. Morgenthau even had his secretary take shorthand notes during his telephone conversations with the President.

9 The Yale University microfilm edition of the Stimson Diaries contains a description by the Project Staff of the way in which the secretary of war composed his record of events during the period 1940–1945.

10 The assertion that "the Japanese are notorious for making an attack without warning" may have been made by FDR, but it was an idea that Stimson (and Hull) shared. It had originated at the time of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905. Events in Manchuria in 1931 and in China proper in 1937 had given new life to the accusation.

11 The men who were present at this meeting on November 25 may have had a diplomatic rather than a military maneuver in mind—perhaps a new warning that aggressive action by Japan would result in consequences of the most serious nature. "I pointed out to the President," Stimson noted, "that he had already taken the first steps towards an ultimatum in notifying Japan way back last summer that if she crossed the border into Thailand she was violating our safety and that therefore he had only to point out that [a Japanese move into Thailand now would be] a violation of a warning we had already given." Stimson Diaries, Nov. 25, 1941, roll 7, 36: 49.

Stimson's declaration that Roosevelt had already moved toward "an ultimatum" seems to me to be incorrect, but the secretary of war may have been referring collectively to three separate steps taken by the President (none of which was an "ultimatum"): 1) his July 24 proposal to neutralize French Indochina, 2) the inclusion of Thailand in that proposal in a statement made on July 31, and 3) a so-called warning to Japan on August 17 (the original text had been toned down by the State Department; the final version was soft-pedaled by the President when he presented it to the Japanese ambassador). FRUS: Japan, 1931–1941, 2: 527–530, 539–540, 556–557. See also Butow, John Doe Associates,, pp. 230–231, 238, 249–251, 415, 418, 420.

12 The intercepts for this period have been printed in Hearings Before the Joint Committee [of the 79th Congress] on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack (1945–1946), pt. 12, and in a Department of Defense publication, The "Magic" Background of Pearl Harbor (5 vols. in 8 books, 1977–1978). Additional primary sources can be consulted at the National Archives, at the Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, PA, and at the Naval Historical Center in Washington, DC (hereinafter NA, MHI, and NHC, respectively).

13 In an army-navy agreement signed on January 25, 1941, the dissemination of "certain special material" (i.e., the "Magic" intercepts) was spelled out in detail. In the case of the army, the route to the President was through his military aide, but intercepts were to be handed to him "in exceptional cases only." On the navy side, FDR's naval aide would be the channel of transmission, but intercepts would be provided "in exceptional cases only, when directed." Intercepts would be shown to the President, the secretaries of state, war, navy, and the heads of other executive departments only "when indicated as desirable in the public interest." Special Research History (SRH)-106 and SRH-200 (pp. 21-22), MHI. These items are also in Records of the National Security Agency, Record Group 457, NA (hereinafter, records in the National Archives will be cited as RG ___, NA).

The problem of dissemination did not disappear with the outbreak of war. In a February 12, 1944, memorandum for the President, Gen. George C. Marshall wrote: "I have learned that you seldom see the Army summaries of 'Magic' material. For a long time, the last two months in particular, I have had our G-2 organization concentrating on a workable presentation on 'Magic' for my use as well as for the other officials concerned, particularly yourself. A highly specialized organization is now engaged in the very necessary process of separating the wheat from the chaff and correlating the items with past information in order that I may be able quickly and intelligently to evaluate the importance of the product."

"All of the worthwhile information culled from the tremendous mass of intercepts . . . accumulated each twenty-four hours" was being bound into "Black Books" at the rate, sometimes, of two or three booklets in a single day. The chief of staff noted that he was attaching two of the current Black Books to his memo so that FDR could familiarize himself with the way in which the information was presented. "I should like," Marshall added, "to send these booklets each day direct to the White House and have them delivered to you by Admiral Brown [Wilson Brown was the President's naval aide at the time in question]."

Marshall's suggestion stemmed from his having just learned that Adm. William D. Leahy, the President's chief of staff, only rarely passed the booklets along to the Oval Office. SRH-040, MHI (also in RG 457, NA).

14 Tel. No. 44, Aug. 2, 1941 (covering the period July 16–24), transl. Oct. 13, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, p. 310. For a broader view of Japanese intelligence activity, see Exhibit No. 2 in ibid., pp. 254–316, and the espionage intercepts printed in "Magic" Background.

15 See Tel. No. 83, Sept. 24, 1941, transl. Oct. 9, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, p. 261; "Magic" Background, vol. 3, Appendix: No. 356; testimony of Sherman Miles, Acting Asst. Chief of Staff, G-2,pt. 2, pp. 794–800, Kramer testimony, pt. 9, pp. 4176–4179, 4193–4198, and Bratton testimony, pt. 9, pp. 4526, 4533–4535, all in Pearl Harbor Hearings. See also Tel. No. 111, Nov. 15, 1941, transl. Dec. 3, and Tel. No. 122, Nov. 29, transl. Dec. 5, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, pp. 262–263; "Magic" Background, vol. 4, Appendix: Nos. 279 and 288; Tel. No. 83, vol. 5, box 57, Pearl Harbor Liaison Office (PHLO), General Records of the Department of the Navy, 1798–1947, RG 80, NA; Tel. No. 111, vol. 7, roll 2, Microfilm Roll No. 1975-1, "Records of Judge Advocate General Relating to Inquiries into the Pearl Harbor Hearings" (hereinafter JAG records), NHC.

The available evidence, which is sketchy, circumstantial, confusing, and inconclusive, suggests that Tel. No. 83 may not have been delivered to the White House. Kramer testimony, pt. 9, pp. 4196–4197, Bratton testimony, pt. 9, p. 4526, Beardall testimony, pt. 11, pp. 5270–5271, 5276–5277, and dissemination of "Magic" intelligence to the White House, all in Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 11, pp. 5474–5476.

The espionage agent in question was a former Imperial Japanese Navy officer, Takeo Yoshikawa, who served as "titular chancellor" of the consulate general in Honolulu, using the name Tadashi Morimura. He received instructions from and reported to the naval authorities in Tokyo by means of the diplomatic codes and ciphers employed by the Japanese Foreign Office and by Consul General Nagao Kita.

The U.S. Pacific Fleet's intelligence officer has described the dimensions of the problem: "Every port and naval base in the United States as well as the Panama Canal, the Philippines and the British, Dutch, and Australian territories in the Far East were already under intensive surveillance. By 1941, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was keeping detailed files on 342 suspected Japanese agents operating throughout the United States. Their movements were monitored, as it was widely believed that many were engaged in espionage directed from the Japanese embassy in Washington and Japan's main consulates in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Honolulu." Rear Adm. Edwin T. Layton, USN (Ret.), with Capt. Roger Pineau, USNR (Ret.), and John Costello, "And I Was There": Pearl Harbor and Midway—Breaking the Secrets (1985), pp. 103–104.

16 Kramer testimony, pp. 4176–4179, 4193–4198, and Bratton testimony, pp. 4526, 4533–4535, pt. 9, Pearl Harbor Hearings. Upon reading Tel. No. 83, Col. Rufus S. Bratton, chief of the far eastern section of the Military Intelligence Division (G-2), War Department General Staff, "felt that the Japanese were showing unusual interest in the port at Honolulu," but his suspicions were allayed by assurances given on several occasions by his "opposite numbers in the Navy" (Bratton may have been referring to Comdr. Arthur H. McCollum, chief of the far eastern section of the Office of Naval Intelligence, and Lt. Comdr. Alwin D. Kramer, who was on loan from McCollum's section to the translation section, Communications Division, Navy Dept.). Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 9, pp. 4508–4509, 4534. Aside from Bratton, apparently the only other officer who reacted to Tel. No. 83 with alarm was Comdr. Laurence F. Safford, chief of the security section of the Communications Division, Navy Department, but questions have been raised about the manner of his approach to the problem. See Gordon W. Prange with Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, Pearl Harbor: The Verdict of History (1986), pp. 278–279. Army and navy officers are identified in the text and notes of this article by the rank each man held in 1941.

For background information and for various interpretations of Washington's failure to evaluate the Honolulu espionage messages correctly, see Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision, pp. 211–214, 373–376, 390–396; Gordon W. Prange with Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor (1981), pp. 248–257, 370–371, 628, 632, 707, 723–724, 734–736, 818–822 (a "List of Major Personnel"); Layton et al., "And I Was There," pp. 161–168, 244–245, 279–281; Prange et al., Pearl Harbor: The Verdict of History, pp. xix–xxii (a glossary of key figures), xxvi–xxvii (simplified organizational charts of the War and Navy Departments), 132–133, 215–218, 262, 273–284, 656.

17 Some officers in Washington may not have read Tel. No. 83. They may have passed over it after looking at only a gist of its contents—a bare bones summary consisting of a single sentence (marred by a typographical error) that did not adequately convey the sense of the original because too much had been left out: "Tokyo directs special reports on ships with [sic] Pearl Harbor which is divided into 5 areas for the purpose of showing exact location." The officer who prepared this gist used an asterisk to indicate to recipients that No. 83 was an "interesting" message. If he had added a second asterisk, they would have realized that he considered the intercept to be an "especially important or urgent" message. The exact number of "Magics" in the delivery batch that contained Tel. No. 83 is not known, but there were more than twelve intercepts in the pouch, together with a "gist sheet" that provided summaries of all of the messages in that particular batch. "Enclosure (A) to Memo from CNC to Rear Adm. Colcough dated 6 November 1945" (which contains part of Gist No. 236-41, Oct. 10, 1941), box 2, and Joseph R. Redman, chief of naval communications to Rear Admiral Colcough, Nov. 6, 1945, R#39, box 15, PHLO, RG 80, NA; Kramer testimony, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 9, pp. 4195–4198.

18 See "Messages Translated After 7 December 1941," Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, pp. 263–270, esp. Tokyo to Honolulu, Nos. 123 and 128, Dec. 2 and 6, 1941, and No. 253, Honolulu's reply, Dec. 6. A "Magic" processing note appended to No. 123 of Dec. 2 states: "This message was received here on December 23."

In 1941 interrelated telegrams did not always emerge from the "Magic" processing mill in proper sequence. In the present instance, Tokyo's inquiry, No. 123 of December 2 (encrypted in J-19), was translated on December 30 but the follow-up message of December 6, No. 128 (in PA-K2), was translated on December 12. Honolulu's No. 253 of December 6 (in PA-K2), which was a reply to both of the above messages, was translated on December 8, four days before the follow-up was processed, twenty-two days before the original inquiry was rendered into English, and one day after the attack. This haphazard sequence is a good illustration of some of the problems that existed in an operation that was still in the early stages of development.

19 Tel. No. 253, ibid., p. 269. Translations could sometimes go awry. Postwar investigation revealed that an officer attached to the Fleet Radio Unit, Pacific Fleet, had rendered the dead-giveaway "surprise attack" sentence as "The whole matter seems to have been dropped." No damage was done in this instance because he had worked on Tel. No. 253 "on or about 10 December 1941, and certainly not prior to 9 December 1941." Baecher memo to Correa, Oct. 17, 1945, R#48, box 15, PHLO, RG 80, NA.

20 Tel. No. 254 (in PA-K2), Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, p. 270. See also Miles testimony, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 2, pp. 794–800.

21 See Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision, pp. 170–176; David Kahn, The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing (1967), pp. 9–13, 27–31, 979, 981–982.

In 1941 "some messages were missed due to static, atmospheric disturbances and incomplete coverage of all frequencies." Other telegrams were simply not translated. Even so, a U.S. Navy analysis of Japanese diplomatic traffic on the Tokyo-Washington circuit for 1941 shows that 444 messages were available out of a total of 912 (88 out of 140 in November; 32 out of 55 for December 1–7). On the Washington-Tokyo circuit, "Magic" processed 607 of the 1,281 telegrams the Japanese embassy sent to the Foreign Office (121 out of 200 in November; 27 out of 59 during the first seven days of December). Exhibit 60, enclosure A, box 75, PHLO, RG 80, NA.

22 The Memoirs of Cordell Hull, vol. 2 (1948), p. 1074; intercept of Tel. No. 812, Nov. 22, 1941, transl. the same day, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, p. 165; "Magic" Background, vol. 4, item 75, and Appendix: No. 162. On November 24 Hull learned from another intercept, which may have been seen by FDR as well, that the November 29 deadline was in Tokyo time (November 28 in Washington). Intercept of Tel. No. 823, Nov. 24, 1941, transl. the same day, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, p. 173,; "Magic" Background, vol. 4, item 75, and Appendix: No. 163. Writing after the war, Hull described his reaction in these words: "The sword of Damocles that hung over our heads was therefore attached to a clockwork set to the hour." Hull Memoirs, 2: 1077.

23 FRUS 1941, 4: 648–649, esp. pp. 649 and 649 n. 81 (FDR's message of Nov. 24 concerned a proposal for a modus vivendi offered by Tokyo on November 20 and an American alternative thereto that was then under consideration in Washington).

24 In his diary, Stimson noted that five Japanese divisions had come from Shantung and Shansi provinces to Shanghai, where "they had embarked on ships—30, 40, or 50 ships." He informed Hull by telephone and subsequently sent him a copy of a military intelligence report in this regard. Another copy went to the President. Stimson Diaries, Nov. 25, 1941, roll 7, 36: 49. A copy of the memo Stimson sent to FDR is in Research File: Japan, George C. Marshall Research Library, Lexington, VA.

When the secretary of war spoke with the President by telephone on the morning of November 26, Roosevelt said that the movement of these Japanese ships changed the whole situation because the presence of this expedition was evidence of bad faith on the part of Japan. Stimson Diaries, Nov. 26, 1941, roll 7, 36: 50–51; Langer and Gleason, Undeclared War, p. 892; Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision, p. 243, citing Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 11, p. 5453 (the aforementioned Stimson entry for November 26).

That same day, Stimson updated his earlier memo to the President by adding a single sentence: "Later reports indicate that this [convoy] movement is already under way and ships have been seen south of Formosa." Folder 28: Stimson to FDR, Nov. 26, 1941, box 138, Stimson Papers, Yale University Library, New Haven, CT; folder: War Dept.—Stimson, 1940–41, Departmental Correspondence, War Dept.—Stimson, President's Secretary's File, FDR Library (also in Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 20, p. 4476); folder 30, box 80, Marshall Papers, and Edwin M. ("Pa") Watson to the secretary of war, Nov. 27, 1941, Research File: Japan, Marshall Library.

25 The Hull note of November 26 consisted of an explanatory "Oral Statement" (despite the terminology, the text was handed to Nomura and Kurusu) and an "Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan" (which was also given to them). See FRUS: Japan, 1931–1941, 2: 371–375, 764–770; FRUS 1941, 4: 709–711; Hull Memoirs, 2: 1080–1086; Butow, Tojo and the Coming of the War, pp. 337–343 and passim; Butow, John Doe Associates, pp. 301–302, 442–443.

Nomura's report to Tokyo, No. 1189, Nov. 26, 1941, was intercepted by "Magic" and was translated two days later. Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, pp. 181–182; "Magic" Background, vol. 4, item 85, and Appendix: Nos. 190–191.

26 This vital information did not become available to "Magic" until June 4, 1945. On that day, documents that had been recovered from a Japanese cruiser were translated. They revealed that Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto had issued his operational orders for the Pearl Harbor attack on November 5 and 7, 1941. "Magic" Background, vol.4, item 16-A.

27 Japan's First Air Fleet (the task force that attacked Pearl Harbor) departed from Hitokappu Bay, Etorofu Island, in the Kurile chain at 6 A.M. on Wed., Nov. 26 (4 P.M., Tues., Nov. 25, in Washington). Prange et al., At Dawn We Slept, p. 390.

The initial discussion of the Hull proposal took place in Tokyo on November 27, based on a gist contained in separate reports from the Japanese military and naval attachés in Washington. Butow, Tojo and the Coming of the War, p. 343.

28 In a Foreign Office message sent to Nomura and Kurusu on November 28, telling them that "the negotiations" would soon be "de facto ruptured," the Hull note was described as a rifujin naru tai-an. The effect in English depends on the way the adjective modifying tai-an (counterproposal) is translated. Among the choices are "unreasonable," "unjust," "unfair," "absurd," or "outrageous." The army translator at "Magic" came up with "humiliating." See Butow, Tojo and the Coming of the War, p. 400 n. 68. The intercepted version of this message, Tel. No. 844 of November 28, was translated that same day. Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, p. 195; "Magic" Background, vol. 4, item 93, and Appendix: No. 214 (see also No. 213, an intercepted circular telegram of November 28 that was not translated until December 9); Tel. No. 844, vol. 8, roll 2, Microfilm Roll No. 1975-1, JAG Records, NHC.

One of the reasons why the two governments were still so far apart, and why Tokyo reacted so negatively to the contents of the Hull note, is that the unauthorized activities of the "John Doe Associates," who had been working behind the scenes for months, had been cumulatively very disruptive. Their proposals had injected considerable confusion into the Hull-Nomura conversations, especially on the Japanese side. See Butow, John Doe Associates, pp. 294, 373–374 n. 107, and passim.

29 The men in the State Department who were concerned with this problem envisaged a gradual withdrawal of Japanese troops from the occupied areas of China south of the Great Wall. See, for example, FRUS: Japan, 1931–1941, 2: 617 and FRUS 1941, 4: 548, 582, 593–594. A December 2 memo by Maxwell M. Hamilton (FRUS 1941, 4: 710) also sheds light on this matter.

In Telegram No. 1191, sent by Nomura on November 26/27, Hull is represented (in the "Magic" translation of November 29) as having told Nomura and Kurusu that "the evacuation [of Japanese forces from China and Indochina] would be carried out by negotiations. We are not necessarily asking that it be effected immediately." See Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, pp. 183–185, esp. 184–185, item (5); "Magic" Background, vol. 4, Appendix: Nos. 192–195.

The intercept of Tel. No. 1191 is dated November 26; the Japanese original indicates that this message was dispatched on November 27. See Gaimushō (hensan), Gaikō Shiryō: Nichi-Bei Kōshō Kiroku no Bu, Shōwa Jūroku Nen Nigatsu yori Jūnigatsu made (1946), Shiryō 5, pp. 487–489. In regard to the statement attributed to Hull, Nomura's telegram reads as follows: "teppei wa yōsuru-ni kōshō ni yoru shidai ni sh'te kanarazu-shimo sokuji jitsugen wo shuchō shioru shidai ni arazu" (p. 488).

30 A preliminary draft of the troop withdrawal clause (Paragraph No. 3) had parenthetically excluded Manchuria, which was covered in a separate clause (Paragraph No. 6): "The Government of the United States will suggest to the Chinese Government and to the Japanese Government that those Governments enter into peaceful negotiations with regard to the future status of Manchuria." Hull's political adviser for the Far East, Stanley K. Hornbeck, recommended removing this clause. He wrote in the margin: "Leave this to be brought up by the Japanese." As a consequence, Paragraph 6 was dropped from the text of the note Hull handed to Nomura on November 26. FRUS 1941, 4: 645–646, 664–665, 710.

31 While talking with Hull on November 26, Nomura had requested a meeting with the President. FRUS: Japan, 1931–1941, 2: 764–766, 770–772 and FRUS 1941, 4: 670–671; Appointment Diaries (Kannee and Tully copies), boxes 83 and 85, President's Personal File, 1-0, FDR Library; Hull Memoirs, 2: 1086–1087; Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 12, pp. 192-95, intercept of Tel. No. 1206, Nov. 27, 1941 (parts 1–3 were translated on November 29; part 4 on December 2); "Magic" Background, vol. 4, item 90, and Appendix, Nos. 207–208.

32 Memorandum for the President from Marshall and Stark, Nov. 27, 1941, on the Far Eastern situation, item 1811, roll 51, Microfilm Copy of OCS 18136-125, Marshall Library; Butow, John Doe Associates, pp. 302–303, 443. In case Japan moved into Thailand, Marshall and Stark thought the American, British, and Dutch governments should warn Tokyo that an advance west of 100° east longitude or south of 10° north latitude might lead to war. Their reasoning was that a Japanese advance of this magnitude would threaten Burma and Singapore. Prior to the issuance of such a warning, however, Marshall and Stark urged that "no joint military opposition" be undertaken against Japan. They also advised the President that a movement of Japanese forces into Portuguese Timor, New Caledonia, or the Loyalty Islands would provide grounds for taking military counteraction.

33 Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 2, pp. 613–615 (corrected: pt. 11, p. 5309). At issue was an allegation that had been made in the 1944 report of the Army Pearl Harbor Board. See also R#161, box 19, PHLO, RG 80, NA.

34 Dec. 3, 1941, Presidential Diaries, 4: 1037, Morgenthau Papers, FDR Library. The text of the President's inquiry concerning Indochina was conveyed to Nomura and Kurusu on December 2 by Sumner Welles acting for Hull, who "was absent from the Department because of a slight indisposition." FRUS: Japan, 1931–1941, 2: 778–781. On November 29 Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox had informed FDR: "The news this morning indicates that the Japs are going to deliberately stall for two or three days, so unless this picture changes, I am extremely hopeful that you will get a two- or three-day respite down there [in Warm Springs, Georgia] and will come back feeling very fit." FRUS 1941, 4: 698.

35 Kahn, The Codebreakers, p. 43; 1946 testimony of Rear Adm. John R. Beardall, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 11, pp. 5284–5285, 5513. In 1941 Beardall, then a captain, was FDR's naval aide.

36 Stimson Diaries, Dec. 6, 1941, roll 7, 36: 80.

37 Nov. 28, 1941, pp. 57–59, ibid.; Butow, John Doe Associates, pp. 303–304, 444. Stimson's diary entry reads: "This, I think, was a very good suggestion on [FDR's] part and a very likely one."

38 Parts 1 to 13 of Tel. No. 902 had begun to arrive in Colonel Bratton's office "in the late afternoon or early evening" of Sat., Dec. 6, but they had come in "all mixed up" rather than in proper numerical sequence. The last of the thirteen parts reached him "sometime between 9 and 10 that night." He considered the message "relatively unimportant militarily that evening." Parts 1 to 13 "contributed no additional information [to what was already available from "Magic" and other sources] as to the impending crisis with Japan. The message was incomplete. . . . It was not an ultimatum, it was not a declaration of war, nor was it a severance of diplomatic relations." Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 9, pp. 4512, 4513, 4516. For the interception record, see Baecher to Mitchell, Nov. 29, 1945, R#36, box 15, PHLO, RG 80, NA.

39 Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1950 rev. ed.), pp. 426–427; 1946 testimony of Comdr. Lester R. Schulz (who delivered the intercept to FDR on the evening of Dec. 6, 1941), Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 10, pp. 4659–4672. At that time Schulz was a navy lieutenant temporarily serving as a communications watch officer under the President's naval aide, Captain Beardall). Beardall testimony, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 11, pp. 5270–5273, 5276–5279, 5280–5281; Kahn, The Codebreakers, pp. 1–5, 49–59, 976–978, 983–985; Langer and Gleason, Undeclared War, pp. 932–937; Butow, Tojo and the Coming of the War, pp. 372–387; Feis, Road to Pearl Harbor, p. 340; Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision, p. 273.

40 The text of Japan's final note, which was officially presented to the secretary of state by the Japanese ambassador shortly after 2:20 P.M. on Sunday, December 7, 1941, is printed in FRUS: Japan, 1931–1941, 2: 380–384 and 787–792. The "Magic" intercept version, in the form of Tel. No. 902, had been read by Hull during the course of the morning. Hull Memoirs, 2: 1095; Bratton testimony, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 9, pp. 4510, 4512, 4513–4516, and Tel. No. 902, pt. 12, pp. 239–245 (parts 1–13 of No 902, sent in English on December 6, 1941, in a cipher that "Magic" were called "Purple," decrypted on December 6; Part 14 of No. 902, sent in English on December 7 in "Purple," was decrypted that same day); "Magic" Background, vol. 4, Appendix: No. 241A; Tel. No. 902, vol. 9, roll 2, Microfilm Roll No. 1975-1, JAG Records, NHC (also in "Narrative Summary of Evidence at Navy Pearl Harbor Investigations," pp. 600–607, 621 box 31, PHLO, RG 80, NA).

The President shrugged at the meaning of Part 14. He told his naval aide that it looked as though the Japanese were going to break off negotiations (i.e., the talks Hull had been having with Nomura). Apparently FDR did not make any other comments. "We never discussed 'Magic,'" Capt. Beardall said. Kahn, The Codebreakers, pp. 56–57, 984; Beardall testimony, Pearl Harbor Hearings, pt. 11, pp. 5273–5275, 5282–5283, 5288–5289, 5513.

41 In this connection, see Butow, "Marching Off to War on the Wrong Foot: The Final Note Tokyo Did Not Send to Washington," Pacific Historical Review 63 (February 1994): 67–79.

42 See, for example, Samuel Flagg Bemis, "First Gun of a Revisionist Historiography for the Second World War," The Journal of Modern History 19 (March 1947): 55–59; Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., "Roosevelt and His Detractors," Harper's Magazine 200 (June 1950): 62–68; Samuel Eliot Morison, "History through a Beard" in By Land and By Sea (1953), pp. 328–345 (a shorter version appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in August 1948); Dexter Perkins, "Was Roosevelt Wrong?" The Virginia Quarterly Review 30 (Summer 1954): 355–372; Robert H. Ferrell, "Pearl Harbor and the Revisionists," The Historian 17 (Spring 1955): 215–233; Herbert Feis, "War Came at Pearl Harbor: Suspicions Considered," The Yale Review 45 (March 1956): 378–390.

See also John McKechney, S.J., "The Pearl Harbor Controversy: A Debate Among Historians," Monumenta Nipponica 18 (1963): 45–88; Martin V. Melosi, The Shadow of Pearl Harbor: Political Controversy over the Surprise Attack, 1941–1946 (1977); Prange et al., At Dawn We Slept, pp. xi–xii, 839-852; Telford Taylor, "Day of Infamy, Decades of Doubt," New York Times Magazine, Apr. 29, 1984, p. 106ff; Frank Paul Mintz, Revisionism and the Origins of Pearl Harbor (1985); Alvin D. Coox, "Repulsing the Pearl Harbor Revisionists: The State of Present Literature on the Debacle," Military Affairs 50 (January 1986): 29–31.

43 From a column written for The Standard (Beacon, NY), Aug. 16, 1928, reproduced in F.D.R., Columnist: The Uncollected Columns of Franklin D. Roosevelt, ed. Donald Scott Carmichael (1947), p. 110.

44 I wish to thank William B. Stoebuck, professor of law at the University of Washington, for guiding me through various standards of proof and other points of law.

45 Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins, pp. 427–429, 956 n. 428 (a Hopkins memo of January 24, 1942, written immediately after a conversation with the President).

46 Michael F. Reilly as told to William J. Slocum, Reilly of the White House (1947), p. 5.

47 Frederick D. Parker, "The Unsolved Messages of Pearl Harbor," Cryptologia 15 (October 1991): 295–313 (esp. pp. 295–298 and 312), notes that intelligence authorities in Washington in 1941 assigned a higher priority to Japan's diplomatic codes and ciphers than to the cryptographic systems used by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). Considerable effort was also expended on operating a direction-finding network to track German submarines in the Atlantic on a twenty-four-hour basis. These activities drained resources away from the U.S. Navy's continuing efforts to master JN-25, the IJN "Operations Code" (a k a the "General Purpose Code").

The first decrypts had been produced in September 1940 after a year of effort. Then, on December 1, "JN-25A," as the Americans called this system, was superseded by "JN-25B," producing overnight "an almost total blackout of Japanese naval intelligence." As far as the U.S. Navy was concerned, JN-25B "was never . . . to yield [prior to Pearl Harbor] more than a partial readability [estimated on good authority at probably about 10 to 15 percent as of November 1941, although an unsubstantiated claim that 50% was readable has been made, possibly with a later date in mind]." Layton et al., "And I Was There," pp. 76–78, 94–95, 534 n. 5, 547 n. 27, 581, and passim.

A "minor variation," introduced by Tokyo on December 4, 1941, "completely frustrated analysis for several months," delaying readability until sometime in February 1942. Soon thereafter, navy cryptanalysts were able to read all JN-25B intercepts. This happy state of affairs lasted only until May 27, when a new enciphering pattern plunged the American side into darkness once again. Parker, "Unsolved Messages," p. 298, and "A Priceless Advantage: COMINT in the Battles of Coral Sea and Midway," Cryptologic Quarterly (issue number unavailable), pp. 79, 85. See also pp. 20 and 54 of an expanded version of the COMINT article published in Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency, United States Cryptologic History, series 4, World War II, vol. 5 (1993).

48 After the war in the Pacific had ended, U.S. Navy analysts in Washington turned their attention to an "enormous backlog of unexploited prewar [IJN] material" from which they decrypted 26,581 messages "in seven different cryptographic systems" covering the critical months from September 5 to December 4, 1941 (the date on which the introduction of a new additive book had rendered JN-25B unreadable until February 1942). Of the 2,413 decrypts selected for full translation, 188 were found to pertain specifically to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Frederick Parker's review of these messages has convinced him that the raid could have been predicted if these intercepts had been readable in 1941. Parker, "Unsolved Messages," pp. 295–298, 301, 312, and "A Priceless Advantage," p. 79. In Layton's opinion, "the intelligence that could have been extracted from JN-25 [if it had been fully broken and readable in 1941] could have been instrumental in forestalling Japan's attack." Layton et al., "And I Was There," p. 95.