The Creation and Destruction of Ellis Island Immigration Manifests: Part 1

Fall 1996, Vol. 28, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

By Marian L. Smith

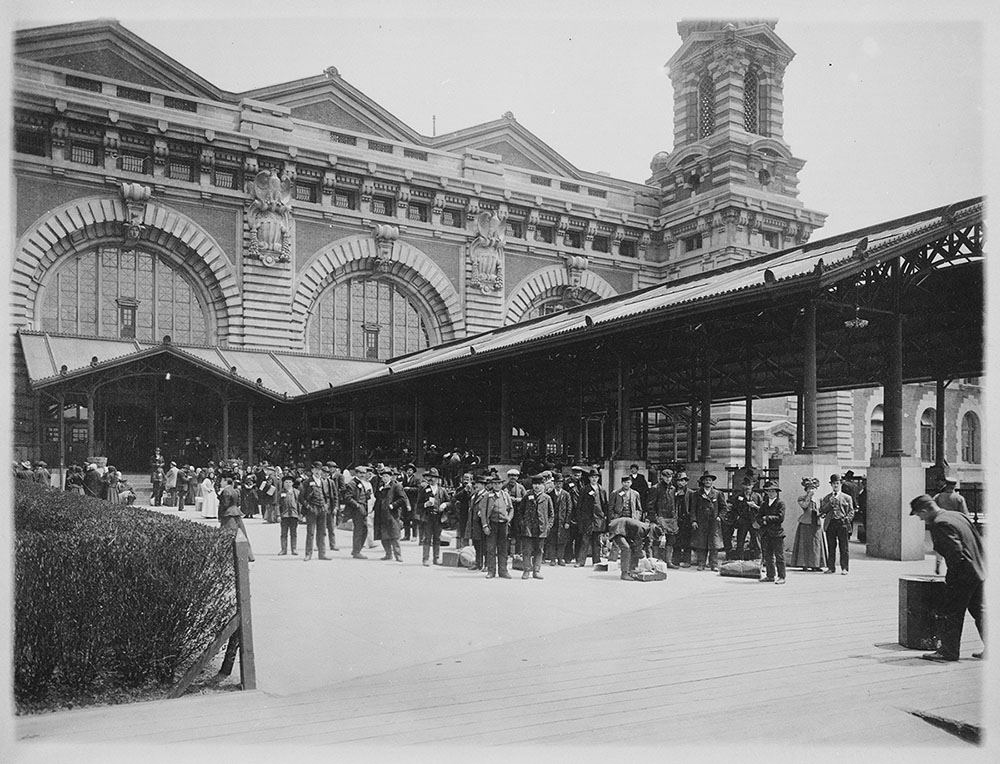

Federal immigration manifests, also known as passenger arrival lists, are among the most popular records at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Researchers using microfilm copies of Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) passenger arrival records are not always satisfied with the film’s quality or legibility and often ask the NARA or INS for access to the original paper manifest. Such frequent requests prompted an investigation into INS's decision to destroy its original records. The result is new insight into the immigration agency’s use of passenger lists and the legacy of the Records Act of 1943. This article recounts Ellis Island manifests’ life in paper form and their preservation on microfilm. Part 2, in the Winter 1996 issue of Prologue, will explain the fate of the original lists.

The federal government began collecting immigration records in 1820 under a law designed to regulate shipping lines carrying immigrants to the United States. The Steerage Act of 1819 required the captain or master of any ship or vessel arriving in the United States to deliver a passenger manifest to a federal official. In those years, the Treasury Department oversaw such matters, and the United States Customs Collector at each port collected passenger manifests as well as cargo manifests. Known as "customs manifests," these lists were to provide each passenger's name, age, sex, occupation, and nationality. The Immigration Act of March 3, 1891, established the Office of Immigration and the Immigration Service within the Treasury Department. After that date, a U.S. Immigration official gathered all passenger manifests, now known as “immigration manifests” after the agency that collected them.1

The 1891 law added two items to the manifest: the last residence of the alien and his or her final destination in the United States. During the early twentieth century, Congress extended the list of required manifest information three times. The Immigration Act of March 3, 1903, stipulated eleven more items; the act of February 20, 1907, one more; and the act of February 5, 1917, six more. This data, which included information about an immigrant's previous home, family, and relations in the United States, has obvious value for family history research.

While various immigration laws increased the information collected on manifests, successive legislation also imposed specifications on the format and completion of manifest forms. The Immigration Act of 1893 required listing immigrants in "convenient groups" of no more than thirty names per page. Immigration Service officers interpreted convenient groups to be members of the same family or those coming from the same town or village. This law also mandated the practice, for inspection purposes, of issuing passengers numbered tickets that corresponded to the page and line number where their name appeared on the manifest.2

Transportation companies had to provide the manifest forms, and regulations under the Immigration Act of 1917 mandated the forms' size, color, and quality of paper. All immigration manifests were to be typed or printed in English. Typed manifests were to use 36-by-18 1/2-inch sheets designated as Form 500. Different colored forms applied to each class of passengers: first class on pink manifests (Form 500), second class on yellow (Form 500A), and steerage on white (Form 500B). Printed sheets were to be either 36 by 18 1/2 inches or 18 by 18 1/2 inches. The smaller sheets were Form 630 (pink), 630A (yellow), and 630B (white).3

The U.S. Bureau of Immigration also furnished transportation companies with blank books to prepare alphabetical indexes and facilitate reference to the manifests. It is unclear when the INS first provided such index books to the companies, how long they did so, or if it intended for the company to submit the index with the manifest. A footnote to the regulations of 1921 states simply that “[t]he practice . . . shall be continued.” Years later, the Immigration Service microfilmed the alphabetical index books as well as the manifests.4

Ship manifests served as the Immigration Service's sole official arrival record for documentation of each admissible immigrant. As such, the manifests were the foundation of inspection procedure and provided the raw data for official immigration statistics. The INS adopted a punch-card system to collect statistics during the earliest years of the twentieth century (probably as early as 1907). Using “punch machines,” immigration clerks in the field converted manifest data to coded holes in cards and forwarded them to the central office for tabulation.5

After the clerks used the manifests for inspection and statistical purposes, they sent them to the station or port's record unit for storage and future reference. Pre–World War II laws and rules regulating the Immigration Service contained no specifics about how those documents were to be filed. The Immigration Service filed manifests at each port just as the Customs Service had since 1819—by date of arrival, then by name of vessel.

Field offices then had their manifests bound into books of about 150 sheets, usually contracting with a local printer or bookbinder to do so. Manifest book spines were typically glued, but many were subsequently nailed, riveted, or stitched to hold the covers and pages together.6 Clerks numbered the books as volumes, then placed them in "bins" or some other sort of shelving. Beginning on December 1, 1924, records personnel at Ellis Island bound all the New York manifests in loose-leaf binders, each binder holding an average of 150 sheets arranged by date of arrival. The binders, too, continued to be consecutively numbered as volumes. One officer of the Immigration Service reported that Ellis Island manifests covering the period from December 1924 to December 1942 filled 6,121 binders. A 1943 document reported the entire collection of manifest volumes stored at Ellis Island numbered 14,100.7

Ellis Island officials, like those at other immigration ports of entry, did not send their manifests to the central office in Washington, DC, because the records were needed for daily use in arrival verification work. Officers might request proof of an immigrant's legal entry (arrival) for a variety of reasons. For example, all applications for Reentry Permits, Certificates of Arrival, or other benefits required checking an application against the original arrival record. As a consequence of the manifest filing system, all requests for verification of arrival had to include the port, date of arrival, and name of vessel, as well as an alien's full name and other identifying information. Search requests of direct arrivals to known ports of entry required only the identifying information, date of arrival, and name of vessel.8

Upon receipt of a request for verification of an alien's arrival, clerks went first to the index book for the specified vessel and date. There the clerk learned the volume, page, and line that contained information about the alien named in the request. The clerk then went to the reference room, found the volume, and placed it on a nearby table. After locating the alien’s name on the page, he transcribed the information from the manifest onto a slip of paper. The clerk returned to the office and typed the handwritten information onto the proper or desired form.9

By the mid-1930s, when the earliest volumes were forty years old, this system of arrival verification began to pose problems for the Immigration Service. The documents’ age and constant use caused deterioration of the paper and ink. As one Ellis Island official explained, “[e]ach evening, after a day's reference work, it was not unusual to observe fragments of pages lying on the floor. Most of these fragments were too small to identify and had to be thrown away. Records of extreme value to the Service as working implements were thus being lost . . . and many pages were rapidly reaching a stage where further rebinding was impossible.”10

A high possibility of error in service operations resulted from the problems of disintegration, fading ink, and the necessity of researching and typing at different locations. That procedure also held few safeguards against the problem of fraud, especially on Ellis Island. Personal contact between Immigration Service employees and “runners” provided ample opportunity for bribes, and the verification process could be abused to create false documents.11

Beginning in November 1935, Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers employed in an indexing project attempted repairs to many of the Ellis Island manifests. They reconstructed and reinforced damaged sheets with “gummed” cellulose acetate and manila tape. Such measures, however, were not adequate for the preservation job ahead.

In late summer 1942, the INS consulted with the National Archives regarding possible methods of rehabilitating or preserving immigration arrival records. The service first considered laminating the sheets but decided this would be impractical because it would double the size and weight of the volumes. Records officers also debated and rejected proposals to photograph the records or to transcribe them manually. By the following spring, INS officers concluded that “[m]icrofilming seemed the nearest approach to the solution of all of our problems.”12

Many sound arguments justified microfilming of the ship manifests. That process would preserve the records—the service's original motive—and reduce the likelihood of error or fraud. Another advantage of microfilm became apparent in 1942, soon after the United States entered into World War II. Until that time, it had always “been the policy of the Service to employ men” as verification clerks because of the bulk and weight (approximately twenty pounds each) of manifest volumes. Several microfilmed volumes weighed only a few ounces, a weight women could certainly lift, and constituted “another reason, in view of the present shortage of male labor, why microfilming is a necessity now.”13

An additional reason for microfilming the manifests became clear in 1943 when the INS moved its New York administrative functions from Ellis Island to 70 Columbus Avenue in Manhattan. During World War II the service, like every federal agency and department, experienced a shortage of office space. Although the INS had taken over the entire building at 70 Columbus Avenue (formerly occupied by the WPA), INS officers in Washington were concerned that the manifest records occupied twenty-five thousand square feet of floor space in the new facility.14

The space problem plagued nearly every federal agency, as did the mounting problem of records storage. Congress responded with the Records Act of July 7, 1943, which provided government agencies with a framework for records management. Official records could be transformed into other, more permanent forms (such as microfilm) or could be retired and stored in federal records centers, where space was less expensive. Equally important, the act also included procedures for destruction of useless or duplicate records. The Records Act certainly offered relief to the INS, which had recently created or obtained many millions of new records as a result of various war-related programs.15

By 1943 New York manifests constituted 60 percent of all INS arrival records. Under the Records Act, INS officers decided to use the New York arrival records as a pilot program. If microfilm copies of manifests proved satisfactory for verification work, the originals would be destroyed, and the service would reduce storage expenses. Accordingly, INS contracted a microfilming firm to duplicate all the New York manifests. As part of the agreement, the contractors trained two INS employees during the project to microfilm records at other ports. Filming began in July 1943, took more than a year to complete, and cost approximately $200,000. They made two copies of the records (one for the INS and one for the National Archives) to prevent any future loss by fire. Microfilmed manifests occupied only five hundred square feet of space in the 70 Columbus Avenue building (2 percent of the original volume).16

With the manifests preserved on microfilm for verification work, INS officials in Washington prepared to destroy the originals under provisions of the Records Act.

The Creation and Destruction of Ellis Island Immigration Manifests: Part 2

Marian L. Smith as been the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service historian since 1988.

Notes

1 Act of March 2, 1819 (Steerage Act), §4; All surviving customs manifests were turned over to the National Archives, where they were microfilmed (microfilm copies are also available at other private institutions). In or around 1974, the Archives transferred the original (paper) customs manifests to the Temple University-Balch Institute Center for Immigration Research. Because the new Immigration Service did not have inspectors at all U.S. ports, many customs inspectors were designated to do immigration inspections as well. While ship captains continued to submit manifests to customs officials at those ports, the records are considered immigration manifests.

2 Immigration Act of March 3, 1891, §8; Act of March 3, 1893, §1-2; Immigration Act of 1917, §13, and 42, rule 2, subdivision 2, Immigration Laws [and] Rules of May 1, 1917, 6th ed., September 1921 (1921), pp. 14–15.

3 Rule 2, subdivision 1, Immigration Laws [and] Rules of May 1, 1917, 7th ed., August 1922 (1922), p. 48; rule 2(C)(2), Immigration Laws and Rules of February 1, 1924 (1924), p. 111.

4 For the alphabetical indexes, see Book Indexes to New York Passenger Lists, 1906–1942 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T612, 807 rolls), Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group 85, National Archives, Washington, DC (hereinafter, records in the National Archives will be cited as RG__, NA); The book indexes are grouped by shipping line and then arranged chronologically by the date of arrival. The same statement appears in a 1922 edition of the same regulations but is not reprinted in subsequent editions. Rule 2, subdivision 1, fn. 2, Immigration Laws [and] Rules of May 1, 1917, 6th ed., September 1921 (1921) p. 42; Interviews with Ira Glazer, Apr. 3, 1992; Sharon Mahoney, INS Verification Center, Martinsburg, WV, Apr. 7, 1992 (telephone); and Constance Potter, Genealogy Specialist, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, Apr. 9, 1992 (telephone).

5 Tabulation equipment was also installed on Ellis Island, the largest immigration station, by 1912. "Immigration and Naturalization Statistics of the United States—Their Nature, Volume, and Method of Compilation," by J. J. Kunna and H. L. Stanforth (Statistical Division, INS), Jan. 7, 1935, INS Lecture Series [2d Series] Number 30, p. 6; The subject index to subject files provided what is known about installation of Hollerith machines on Ellis Island.

6 The subject index to the 56000 Series of records includes many references to contracts and expenditures for the binding of manifests at field offices. For the condition of the manifest books, see Len G. Townsend, “The Microfilming of Arrival Records in the New York District Office of the Immigration and Naturalization Service,” typescript, Nov. 18, 1944, in INS File 56134/715, "NY Manifest Microfilming, 1942–1952,” box 10, accession 85-58A0734, Immigration and Naturalization Service. See also "The Service Microfilms Its Ellis Island Records," [INS] Monthly Review 1 (August 1943): 23–24; and “The Microfilm Project in New York,” Monthly Review 1 (May 1944): 12.

7 Memorandum, INS New York District Administrative Services Officer Ralph H. Holton to Director of Administrative Services Perry M. Oliver, May 12, 1945; memorandum (“Inspection of Ships' Manifests of the Port of New York stored at Ellis Island by the Immigration and Naturalization Service”), Adelaide E. Minogue (Acting Chief, Division of Repair and Preservation) to Director of Records, Accessioning and Preservation, Apr. 14, 1943, INS file 56134/713. The “bins” at Ellis Island were metal shelving that filled the large reference room. Townsend, “The Microfilming of Arrival Records,” p. 1, INS file 56134/715.

8 Ralph H. Horner (Supervisor, Reentry and Exit Permit Unit), "Immigration and Naturalization Documents, Records, and Indexes," May 1, 1943. INS, Course of Study for Members of the Service (unpubl. ms., 1943 [INS History Library, Washington, DC]), p. 2. After July 1, 1924, visa files housed at the central office also documented an alien's arrival. During the late 1930s, the visa files were indexed under the Soundex system. The visa index has allowed name searching for those immigrants who arrived after July 1, 1924.

9 The customary form for this purpose was a Certificate of Admission of Alien, Form 505 (after 1942, Form I-404).

10 Townsend, “Microfilming of Arrival Records,” pp. 1–2, INS file 56134/715.

11 Ibid.; “Memorandum for Mr. Savoretti,” from Operations Advisor Ernest E. Salisbury to Deputy Commissioner Joseph Savoretti, Nov. 27, 1943, INS file 56134/715.

12 WPA Program of Research & Record Reorganization for the United States Immigration & Naturalization Service, Division of Community Service Programs, Planning & Control Section, Program Information Series No. 2 (1941), pp.3, 4.

13 "The Service Microfilms Its Ellis Island Records," Monthly Review 1 (August 1943): 23.

14 Ibid., and INS Annual Report, 1943, p. 26.

15 Act of July 7, 1943 (PL 115, 78th Cong., 1st sess.); “Administrative History of the Immigration & Naturalization Service During World War II,” Aug. 19, 1946, (unpubl. ms., INS History Library, Washington, DC), pp. 63–64. World War II programs included alien registration, internment of aliens of enemy nationality, and military naturalization.

16 Ibid.