"Semper Fidelis, Code Talkers"

Winter 2001, Vol. 33, No. 4

By Adam Jevec

As Americans and Japanese troops fought island to island in the Pacific during World War II, the Japanese used their considerable skill as code breakers to intercept many messages being sent by American forces. After the war, however, Japan's own chief of intelligence admitted there was one code they were never able to break—the Navajo code used by the Marine Corps. This is the story of that code and the men who made it work for the Marines.

Last summer, the U.S. Congress honored a group of World War II veterans who provided a unique service to the nation's war effort. In a ceremony in the Capitol on July 26, the original twenty-nine Navajo "code talkers" received the Congressional Gold Medal, and subsequent code talkers received the Congressional Silver Medal. Their unbreakable code helped the U.S. Marine Corps battle across the Pacific from 1942 to 1945. Until 1968, they and their code remained secret. Their story further comes to national attention when the motion picture Windtalkers opens in June 2002. Written and photographic records in the National Archives document the code talkers' wartime contributions and tell us how this unusual military program got started.

Maintaining secrecy, particularly during wartime, is vital to the national security of every country. On the battlefield, secrecy is essential for victory, and breaking enemy codes is necessary to gain the advantage and shorten the war.

During World War II, sending and receiving codes without the risk of the enemy deciphering the transmission required hours of encrypting and decrypting the code. The U.S. Marine Corps, in an effort to find quicker and more secure ways to send and receive code, enlisted Navajos as code talkers.

Philip Johnston initiated the Marine Corps's program to enlist and train Navajos as messengers. Johnston, the son of a missionary, grew up on a Navajo reservation and became familiar with the people and their language. He was also a World War I veteran who knew about the military's desire to send and receive messages in an unbreakable code. Johnston said he hit upon the idea of enlisting Navajos as signalmen early in 1942, when he read a newspaper story about the army's use of several Native Americans during training maneuvers with an armored division in Louisiana.1 The article also stated that, during World War I, Native Americans had acted as signalmen for the Canadian army to send secure messages about shortages of supplies or ammunition. The U.S. Army's program, however, was never given the priority that the U.S. Marine Corps assigned to Johnston's idea in 1942.

The day after Johnston read the article, he went to the naval office in Los Angeles and told them the story. Believing it had possibilities, the office sent Johnston to the headquarters of the Eleventh Naval District in San Diego, which was convinced that if Johnston's idea could be accomplished, it would be a "marvelous thing." Johnston went on to Camp Elliot in San Diego to meet Maj. James E. Jones. It took him some time to convince Major Jones about the potential for using a Native American code, but after Johnston spoke a few Navajo words to the baffled major, Jones decided to give his idea a trial run. Within two weeks, Johnston assembled four Navajos in the Los Angeles area and arranged to meet Major Jones back at Camp Elliot on February 27, 1942, with the demonstration to occur the next day.

Before returning to Camp Elliot, Johnston sent a preliminary report to Major Jones and Maj. General Clayton B. Vogel, the commanding general of the Amphibious Corps, Pacific Fleet, that explained why he believed Navajos would make the best signalmen. He described his own knowledge of the Navajo people, gave general background and population statistics about Native American tribes, and explained the potential of the Navajo language as a military code. Johnston stressed the complexity of the Navajo language and the fact that it remained mostly "'unwritten' because an alphabet or other symbols of purely native origin" did not exist, with the exception of adaptations by American scholars, anthropologists, and Franciscan Fathers, who had compiled a Navajo dictionary.2

Johnston's proposal also discussed how fluency in reading Navajo could be obtained only by those "individuals who are first highly educated in English, and who, in turn, have made a profound study of Navajo, both in spoken and written form." Besides himself, Johnston claimed that very few people in the world could understand the Navajo language. Because of Johnston's intimate knowledge of the Navajo reservation, its people, and their language, and because the Navajo had the largest population of Native Americans, he believed that they were the best candidates for recruitment. Johnston thought that the tribe's seclusion made the Navajo a culturally and linguistically autonomous people compared with other native groups. The Navajo reservation, which was located largely in Arizona but also comprised portions of New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado, covered an area of twenty-five thousand square miles of isolated, sparsely populated, and largely inaccessible land.

Johnston also believed that many Navajos had been given an education that adequately prepared them for jobs outside their traditional lifestyles. In the years before 1942, Navajo children attended government-established schools on the reservation that taught English grammar. A large number of them also attended schools outside the reservation that offered classes in trades and occupations. With proper training, Johnston was sure that Navajos who fit the age and education requirements for military service could be taught to transmit messages in their native language.

Prior to the demonstration on February 28, 1942, General Vogel had installed a telephone connection between two offices and had written out six messages that were typical of those sent during combat. One of those messages read, "Enemy expected to make tank and dive bomber attack at dawn." The Navajos transmitted the message almost verbatim: "Enemy tank dive bomber expected to attack this morning." The remaining messages were translated with similar proficiency, which duly impressed General Vogel. A week later, on March 6, 1942, Vogel wrote a letter to the US Marine Corps commandant recommending the initial recruitment of two hundred Navajos for the Amphibious Corps, Pacific Fleet.3

After detailing the nature of the demonstration and its success, Vogel outlined the advantages of Johnston's proposal. Vogel noted that the Navajo dialect was regarded as "completely unintelligible" to other tribes and that only twenty-eight Americans were thought to possess a more than superficial knowledge of the language. In addition, Vogel noted that, according to Johnston, the Navajo tribe was the only one that had not yet been infiltrated by Germans posing as students, art dealers, and anthropologists in order to study the various tribal dialects of American Indians. This point was to become moot, as the code talkers were never deployed on the European front. But the statement nevertheless revealed the priorities of Vogel and the military on the whole—to maintain the utmost secrecy and security in their communications.

Although Vogel's letter was firm in its support, it nevertheless alluded to some of the problems that would trouble the project as it progressed. Prior to the demonstration, the Navajo transmitters had been allowed a few minutes to "improvise" words for military terminology not in the Navajo vocabulary. While the demonstration itself was a success, over the next year, the development of a consistent and universally applicable Navajo code for the countless military terms would prove to be a major obstacle. Vogel also stated, on the basis of Johnston's assurances, that one thousand Navajos with the necessary qualifications could be found for the project. When the program eventually expanded, however, meeting such expectations proved difficult.

Other objections soon came to light. One colonel stated that the supposed primary advantage of the code talkers over the encrypted system—speed—was actually of little benefit in the field. When speed was of the essence, messages were usually sent uncoded because the enemy would not have time to intercept them and respond. The colonel also was reluctant to endorse a proposal that would have "combat directing officers depending on an order being translated" in a language that they themselves had no chance of understanding.4

Despite these objections, the initial recruitment of code talkers was approved, with the stipulation that the Navajos meet the normally required qualifications for enlistment, undergo the same seven-week basic training as any other recruit, and meet strict linguistic qualifications in English and Navajo. On May 5, 1942, the first twenty-nine Navajos arrived at the recruit depot in San Diego, California, for basic training, where they were trained in the standard procedures of the military and in weapons use. Afterward, they moved to Fleet Marine Training Center at Camp Elliott, where they received special courses in the transmission of messages and instruction in radio operation.

At Camp Elliott the initial recruits, along with communications personnel, designed the first Navajo code. This code consisted of 211 words, most of which were Navajo terms that had been imbued with new, distinctly military meanings. For example, "fighter plane" was called "da-he-tih-hi," which means "hummingbird" in Navajo, and "dive bomber" was called "gini," which means "chicken hawk." In addition, the code talkers also designed a system that signified the twenty-six letters of the English alphabet. For example, the letter A was "wol-la-chee," which means "ant" in Navajo, and the letter E was "dzeh," which means "elk." Words that were not included in the 211 terms were spelled out using this alphabet.

The Navajos soon demonstrated their ability to memorize the code and to send messages under adverse conditions similar to military action, successfully transmitting the code from planes, tanks, or fast-moving positions. The program was deemed so successful that an additional two hundred Navajos were recommended for recruitment as messengers on July 20, 1942. Philip Johnston offered his services as a staff sergeant to help develop the code talker program. On October 2, 1942, Johnston enlisted and began training his first class in November and spent the remainder of the war training additional Navajo recruits. After the new recruits went through the Marine Corps's basic training course, they came to Johnston for what he termed an "extremely intensive" eight-week messenger training course.

As the code talker program grew, so did the development of the code. A cryptographer who monitored the code talkers' transmissions concluded that the code might be broken because using the alphabet to spell out words not in the Navajos' vocabulary produced too many repetitions. The code talker alphabet therefore grew from twenty-six to forty-four terms by expanding the number of words used for the most frequently repeated letters— E, T, A, O, I, N, S, H, R, D, L, and U. For example, the letter A could be designated by the words "be-la-sana" and "tse-nihl," which mean "apple" and "axe," as well as the original "wol-la-chee," meaning "ant." The original 211 vocabulary terms were also expanded to 411.

By April 1943 the additional two hundred recruits had completed their training, while the initial recruits were attached to marine divisions in the South Pacific. Following recommendations of marine divisions in the field, the Marine Corps determined that the program should be continued and expanded further. According to the new proposal, an additional 303 Navajos were to be recruited at 50 men a month for six months.

The enlistment of additional Navajos was not a simple task, however, because many new recruits were not qualified. In addition, Navajos who volunteered through Selective Service were often sent to other branches of the military. The Marine Corps reduced the quota to twenty-five men a month, made arrangements with Selective Service to activate voluntary induction of Navajos, and even tried to transfer Navajos from the army into the Marine Corps, but its goals still remained unattainable.

On the front lines in the South Pacific, the Navajo code talkers experienced their own varying degrees of success. The official Marine Corps records contain very few battle reports related to the Navajo code talkers, citing activity only at Guam, Palau, Okinawa, and Iwo Jima. Reports from Iwo Jima, typical of those related to code talkers from the front, highlight both the limitations and strengths of the program.

One of the primary limitations was the lack of available qualified Navajos to participate. Many offices, regiments, and battalions remained without the new recruits, which rendered coded communication between these offices and those with the code talkers impossible.

Despite the development of unique military terms for the Navajo code, the lack of military terminology in the original Navajo vocabulary remained an obstacle. Because the Navajo messengers had trained at different times and worked in different locales, the development of certain dialects and modified vocabularies was inevitable. To offset this problem, officers frequently exchanged Navajos from one division into another to try to ensure that all code talkers used a standard code. Problems persisted, however, and after Iwo Jima it was recommended that the Navajos be "thoroughly trained in a standard Navajo military dictionary."5 Quarterly training sessions were advised, in which messengers could review standard Navajo military code, as well as such duties as radio procedure and radio headings, to maintain a high degree of efficiency.

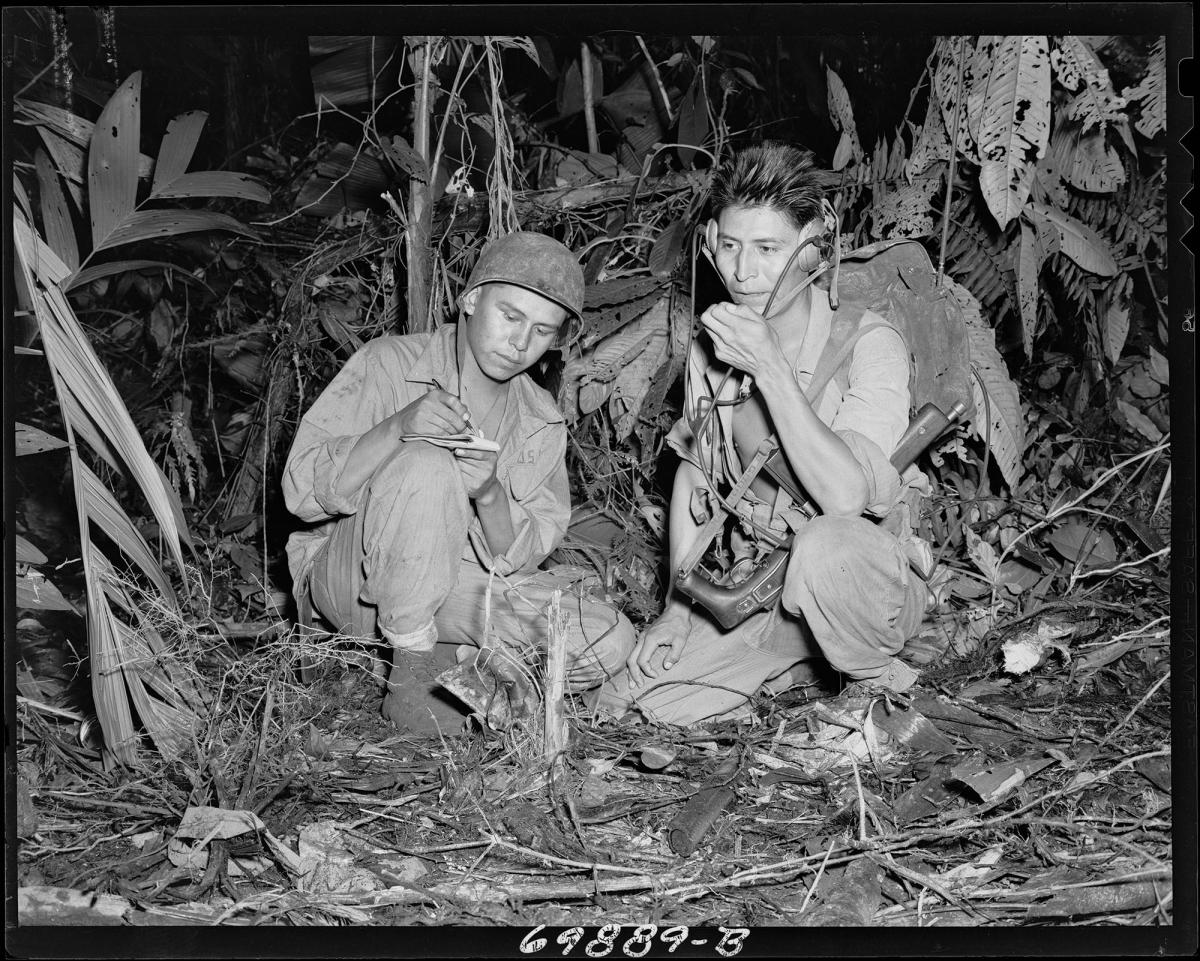

Even with these limitations, overall assessments from Iwo Jima and other battles showed that there was an interest in continuing the development of Navajos as code talkers. The primary strengths of the code talkers were the amount of secrecy that they ensured and the versatility with which they could be used. When compared to other messengers, the Navajos provided a valuable line of communication by radio that was both secure and error-free. Capt. Ralph J. Sturkey, in his Iwo Jima battle report, called the Navajo code the "the simplest, fastest, and most reliable means" available to transmit secret orders by radio and telephone circuits exposed to enemy wire-tapping. Captain Sturkey also wrote that the "full value of Navajo Talkers would not be appreciated until the Commander and Staff they are serving gain confidence in their ability."6 In addition to functioning as messengers who provided a secure means of communication, the Navajos proved at Iwo Jima and other battles to be excellent general-duty marines, useful in a variety of operations.

It is estimated that between 375 and 420 Navajos served as code talkers. The program was highly classified throughout the war and remained so until 1968. Though they returned home on buses without parades or fanfare and were sworn to secrecy about the existence of the code, the Navajo code talkers are now making their way into popular culture and mainstream American history.

The "Honoring the Code Talkers Act," introduced by Senator Jeff Bingaman from New Mexico in April 2000 and signed into law December 21, 2000, called for recognition of the Navajo code talkers. The act authorized the President of the United States to award a gold medal, on behalf of the Congress, to each of the original twenty-nine Navajo code talkers as well as a silver medal to each man who later qualified as a code talker.

The medals were awarded during a ceremony in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol on July 26, 2001. The room was electric with emotion. One of the most moving features of the ceremony was seeing the large number of members of the Navajo nation—both veterans and their families and friends. Many medal recipients were wearing their Navajo Code Talkers Association regalia. Five of the original twenty-nine code talkers are still alive, and four were able to attend the ceremony: Allen June, Lloyd Oliver, Chester Nez, and John Brown, Jr. Family members represented those who could not be present, and they held signs with the picture of their code talkers.

Members of Congress expressed gratitude to the Navajos who had risen above cultural oppression to answer the call when their country needed them and developed the most successful military code of the time. President Bush hailed the code talkers as men "who, in a desperate hour, gave their country a service only they could give." After his remarks, President Bush presented the gold medals, sharing a moment with each veteran.

John Brown, Jr., addressed the assembly, speaking at length about how thankful he was to be honored, his pride in his fellow code talkers, and how important it was to remember the "ultimate sacrifice" paid by the many Americans who lost their lives during the war. After speaking in Navajo for an extended period, Brown received a round of laughter when he joked, "Maybe Japan is listening!"

The most spirited speech of the afternoon came from Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps Alford McMichael, who brought the crowd to its feet when he concluded with these appropriate words: "Semper Fidelis code talkers! Semper Fidelis my fellow Marines! Semper Fidelis my fellow Americans."

Excerpts from the Navajo Code, Part 1; Folder 6, Box 5; History and Museums Division; Records Relating to Public Affairs; USMC Reserve and Historical Studies, 1942–1988; "C" Course to Wash. Daily News; Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, National Archives at College Park.

See also: NARA's Digital Classroom for the Navajo Code Talkers lesson plan.

Notes

1. Interview with Philip Johnston at Flagstaff, AZ, by John Sylvester, Nov. 7, 1970, Doris Duke Number 954, The American Indian History Project Supported by Miss Doris Duke, Western History Center, University of Utah; Folder 5, Box 5; History and Museums Division; Records Relating to Public Affairs; The USMC Reserve and Historical Studies, 1942–1988; "C" Course to Wash. Daily News; Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group (RG) 127, National Archives at College Park (NACP), College Park, MD.

"Indian Jargon Won Our Battles," by Philip Johnston, folder 7, box 5, History and Museums Division, Records Relating to Public Affairs, USMC Reserve and Historical Studies, 1942–1988, "C" Course to Wash. Daily News, Records of the US Marine Corps, RG 127, NACP.

2. Philip Johnston's "Proposed Plan for Recruiting Indian Signal Corps Personnel," folder 13, box 600, Office of the Commandant, General Correspondence, 1939–1950 (Entry 18A), RG 127, NACP.

3. Gen. Clayton Vogel to the Commandant, USMC, Mar. 6, 1942, ibid.

4. Col. Frank Halford, Director of Recruiting, to the Commandant, USMC, Mar. 26, 1942, ibid.

5. Page 26, folder A8.5-1: Signal Questionnaire, box 77, Records Relating to United States Marine Corps Operations in World War II ("Geographic Files"); Iwo Jima; RG 127, NACP.

6. Page 26, folder A16-10: 5th Marine Division "M" to "R," Annex Oboe to 5th Marine Division Action Report of Iwo Jima Operation, box 90, ibid.