Secrecy and Salesmanship in the Struggle for NARA’s Independence

Spring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1

By Robert M. Warner

A splendid new National Archives building in College Park, improved budgets and fiscal resources, a new fund-raising foundation, the remodeling of the original National Archives Building, heightened national visibility—all of these and many other significant improvements in NARA would not have happened if an event had not occurred on October 19, 1984.

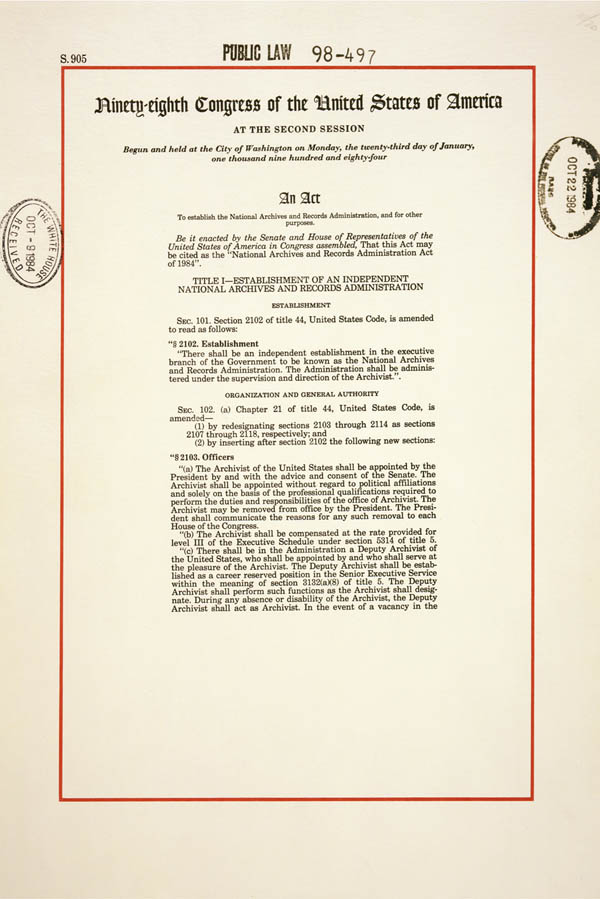

On that day President Ronald Reagan signed Public Law 98-497, which made the National Archives an independent agency as of April 1, 1985. No longer would the Archives be a component of the General Services Administration (GSA).

This major event in the National Archives' history did not just happen. It came about after the passage of a great deal of time, a huge amount of effort, and considerable pain. In September 1950 President Harry S. Truman signed legislation changing the National Archives from an independent agency, as created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934, to a "Service" under the authority of the newly created GSA. This did not turn out to be a happy marriage. A cultural institution dedicated to preserving the greatest documents of American history became a cog in the housekeeping wheel of government.

Gridlock soon developed between the GSA and the National Archives. Historians, archivists, genealogists, and other users of the National Archives began a crusade for independence—to no avail. The agency remained in captivity. In July 1980, I assumed the directorship of an agency that was ripe for change. Among the first-year goals I set for myself was "Tackle Independence," and within three days of my swearing-in the tackling began.

But I was not alone. Many groups and individuals coalesced for the battle. A key group of combatants was from the National Archives itself. To be sure, there was a very small group of dissidents (probably no more than four or five people) who opposed independence, mostly because they had other grievances against senior management. But except for some largely ineffective testimony at congressional hearings, they had little effect. On the other hand, an equally small group of senior managers in the National Archives worked tirelessly and effectively to promote the cause of independence.

Beginning in 1982, a group of six dedicated staff members, joined occasionally by another member or two, met regularly—at first every two weeks, then weekly, and finally toward the end of the campaign, almost daily. These members were smart, well informed, and familiar with the Archives and the workings of government. I chaired the committee, although as head of an agency that reported to the GSA, I had to be particularly circumspect, as were all of my fellow conspirators.

Our meetings were informal with very open discussion. We collected the latest information from our various sources, planned strategy, and passed out assignments to contact key congressional staffers, friends in the archival profession, members of the press, and other allies. These meetings were held in secret.

The very existence of the committee was unknown to the rest of the Archives and certainly to the GSA, whose Administrator was vehemently opposed to independence, as were all of his deputies. The mood at these secret sessions ranged from depression to despair, but the work continued and an internet of opposition was gradually woven and strengthened through the efforts of six people meeting around an office table.

But there were other activities not so clandestine. National Archives senior staff, in Washington and in the field, were extremely helpful and effective. The Lyndon B. Johnson and the Gerald R. Ford presidential libraries, in particular, made key congressional contacts to promote our cause.

Outside of the Archives were other key groups that had a large and effective impact on our efforts. Chief among these professional groups was the American Historical Association (AHA) and its executive director Samuel Gammon. Closely associated with him and the AHA was the National Coordinating Committee for the Promotion of History (NCC), headed by Page Putnam Miller. Page devoted countless hours of effective lobbying for the Archives' cause with members of Congress and their staffs. In addition to the AHA and the NCC, the National Coalition to Save our Documentary Heritage, the Organization of American Historians, the Society of American Archivists, the American Library Association, the National Genealogical Association and other national, state, and local groups were particularly helpful in putting pressure on members of the House and Senate and their staffs.

Certain members of Congress were active on our behalf, introducing legislation, holding hearings on independence bills, and pushing them along the always slow and cumbersome route to passage. Key players in the House were representatives Glenn English of Oklahoma, Jack Brooks of Texas, and Frank Horton of New York. Senators Thomas Eagleton of Missouri, Charles (Mac) Mathias of Maryland, and Mark Hatfield of Oregon championed our cause in their chamber.

Senator Hatfield was especially influential in bringing about a successful conclusion to the campaign. In negotiations with Edwin Meese, special counsel to the President, he agreed to support some Reagan fiscal legislation in return for the President's support of independence for the Archives.

The press, too, played a large role in the independence movement. The Washington Post and The New York Times, as well as other newspaper allies around the country, gave strong and timely support to the legislation. The press coverage had much impact on the Congress and on our constituents around the country and provided encouragement to those working within the Archives itself.

The independence adventure proved that a small agency with no paid lobbyist and little political power can indeed succeed in passing legislation and, most important, proved beyond a doubt that the American political process can and does work. These herculean efforts of individuals, organizations, legislators, and the media proved effective, but the legislative process was a long and difficult one, tense and emotional.

This brief narration of the steps in the struggle for independence cannot convey the emotions involved. Throughout the complex maneuvering there were moments of great disappointment, worry, and frustration as well as elation, excitement, and joy.

This brief narration of the steps in the struggle for independence cannot convey the emotions involved. Throughout the complex maneuvering there were moments of great disappointment, worry, and frustration as well as elation, excitement, and joy.

Hearings were held in the Senate and the House during which the GSA Administrator inadvertently advanced our cause by threatening removal of senior staff, from the Archivist of the United States on down. This abuse of the Archives created a wellspring of sympathy for the Archivist and his troops and actually aided us in our campaign.

The good guys finally won, and on April 1, 1985, the National Archives was "Free at Last."