The Frozen Sucker War: Good Humor v. Popsicle

Spring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1

By Jefferson M. Moak

They are as American as apple pie but as welcome on a hot summer day as a dry, cool breeze from Canada.

They are the frozen ice cream bars and flavored ices that are known today as Good Humor Bars and Popsicles, two American food icons.

The early part of the 20th century was a time when new ideas about ice cream and other confections were popping up, and advances in refrigeration allowed manufacturers to experiment with different shapes and flavors. The ice cream cone, the ice cream bar, the chocolate-coated ice cream on a stick, the ice cream cup—all were developed during the first quarter of the 20th century.

Both the Good Humor Corporation of America and the Popsicle Corporation of the United States were founded upon similar products patented in 1923 and 1924. After face-offs in numerous court battles in at least nine different federal courts from New York to California, they joined forces in 1925 to split the field and protect their joint rights. Their eventual disagreement in 1932 lay in the interpretation of this division. Little fault lay with the lawyers who drew the agreement: the industry itself had not yet reached standard definitions for the composition of ice cream and sherbet.

The Ice Cream "Novelties"

Christian Nelson, an Onawa, Iowa, schoolteacher, patented the Eskimo Pie in January 1922. An instant success, trade magazines raved about it. One retailer declared that "although nobody knew it until it happened, it seems that everybody in these United States was waiting for someone to come along and invent a bar of ice cream coated with sweet chocolate."

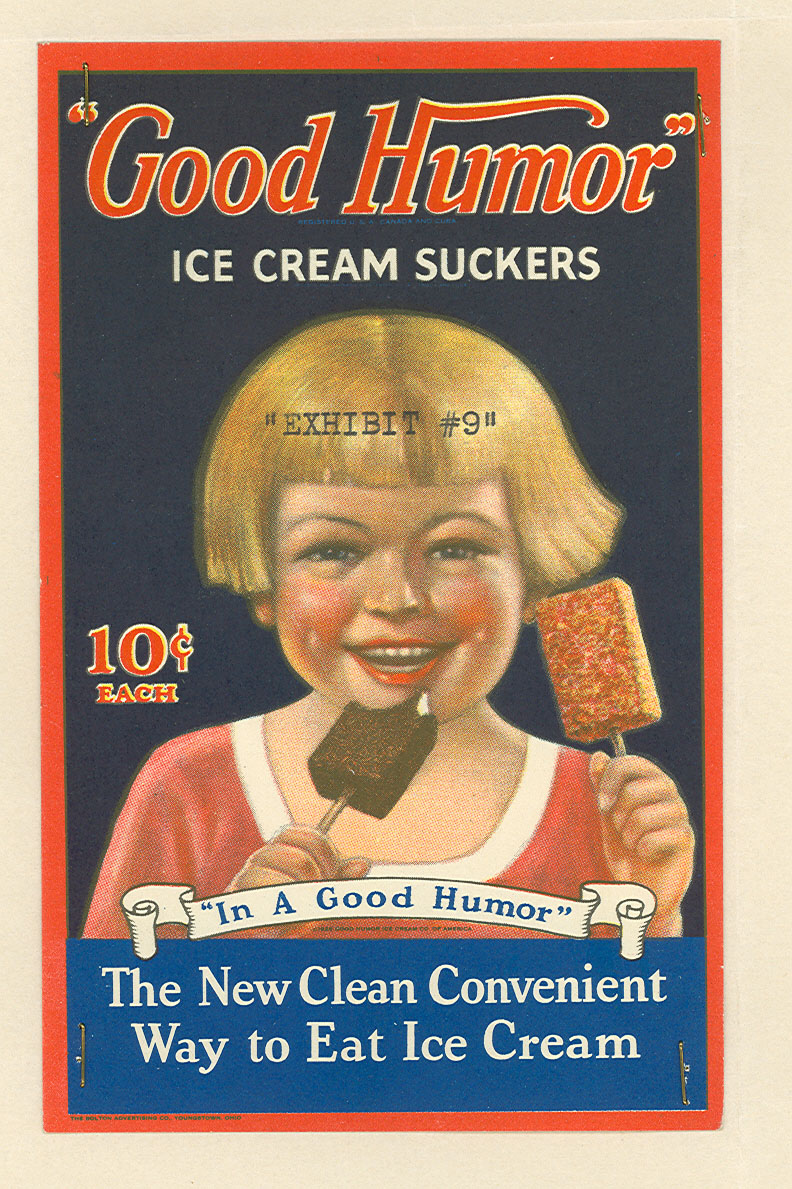

It was only a small jump from a chocolate-covered ice cream bar to an ice cream bar on a stick. Harry B. Burt, a Youngstown, Ohio, confectioner, inserted a stick into the chocolate-covered ice cream bar and created the Good Humor Bar. He announced that this was "the new clean convenient way to eat ice cream."

According to testimony furnished by his widow some 11 years later, Burt developed his frozen confection in 1920 or 1921, before the appearance of the Eskimo Pie. He applied for patents covering the process, the manufacturing apparatus, and the product on January 30, 1922. On October 9, 1923, Burt received the patent for the process and the machinery. No patent was ever granted for the product.

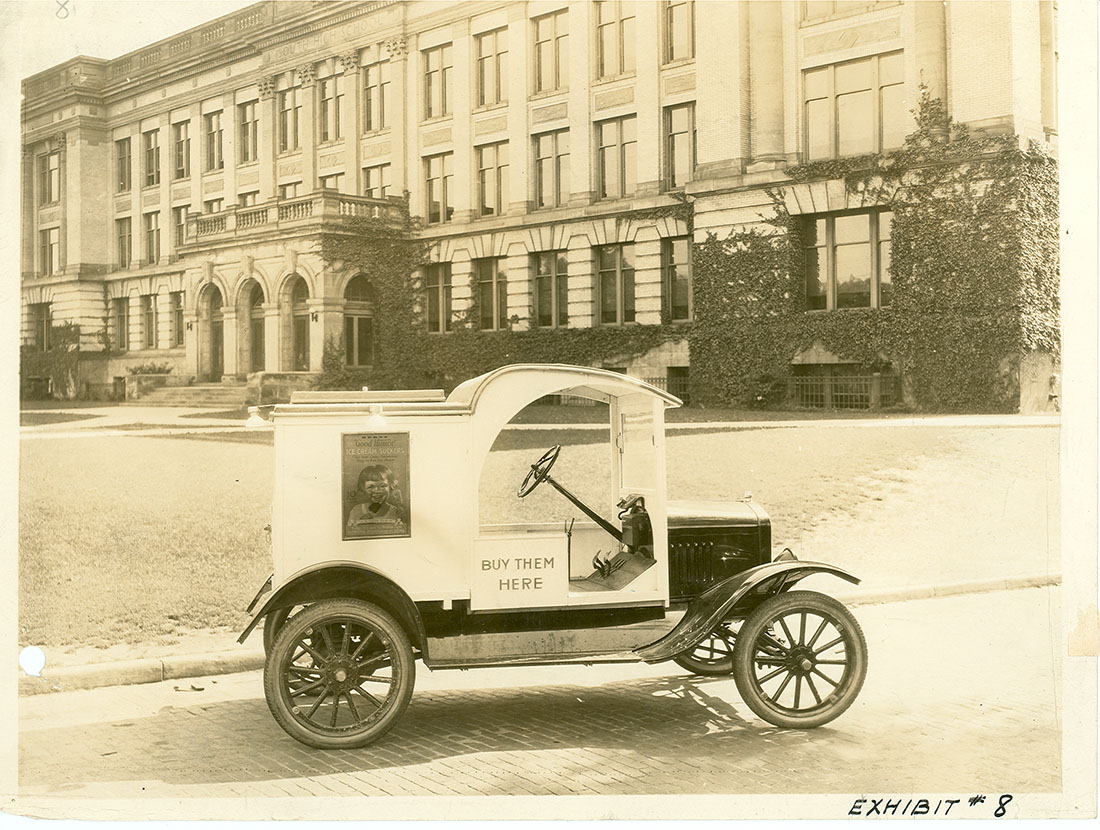

At a time when standardization of products was relatively unknown, Burt wanted to create a national brand name product that would retain the same ingredients and flavor in all markets. Burt's marketing plan involved licensing a select number of manufacturers to make Good Humor ice cream from uniform formulas and molds so that customers purchasing Good Humor Bars anywhere in the country would know that they were getting the exact same product. Burt also improved upon an old method of getting ice cream to the consumer. Like the old-time street vendors, he chose to hawk his product in the neighborhoods rather than at fixed locations. Thus he created the Good Humor Truck, a summer staple in many communities until the 1970s.

Burt, through his patents, claimed ownership of all forms of frozen confections on a stick. In the June 1925 issue of The Ice Cream Review, Burt stated: "[It] is just as much an act of infringement to use a patented process as to make a patented product. The Burt patent is many months ahead of any other patent relating to frozen suckers. Our royalties are small, indeed far less than litigation would cost to be an infringer." He was a man of his word. He soon filed lawsuits against two of his chief competitors: the Citrus Products Company and the Popsicle Corporation.

The "Frozen Sucker"

By filing the suit against Citrus Products in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, Burt acknowledged its sudden emergence in the field. Founded about 1918, Citrus was proud to report that by 1925 it was one of the largest manufacturers of concentrated fruit flavors for the ice cream and beverage industries in the United States and Canada. It also provided the key ingredients for ices and sherbets.

One of Citrus's Texas customers, the M-B Ise Kream Company, introduced in June 1924 a frozen confection or water ice on a stick known as "Frozen Suckers" using the Citrus's "Kist" flavors. M-B Ise Kream reported extensive sales. Citrus exploited the confection by mounting an advertising campaign that featured the product under the name "Frozen Sucker."

Here it is—the Frozen Sucker—the greatest treat you ever tasted—a luscious frozen ice on a stick, flavored with genuine "Kist" Flavors—the best known fruit flavors for frozen products in America. Each Frozen Sucker is individually wrapped to protect its purity—a thousand delights on a stick—pure—sweet—wholesome. Treat yourself—treat the boys and girls—five cents—that's all—everywhere.

By 1925, one competitor noted that the "Frozen Sucker" had "swept the market in a sensational manner."

The frozen sucker was a water ice, not an ice cream. The onset of modern refrigeration and production methods made it cheap to produce and popular with manufacturers. Water ice was in competition with soft drinks rather than ice cream. The June 1925 Ice Cream Review declared, "These novelties are especially useful in combating soft-drink competition. They . . . have quite the same palate appeal as the soft drinks. The suckers and popsicles seem to have won a place for themselves." Many manufacturers were producing both ice cream and water ices. Citrus Products and Popsicle both advised their licensees that adopting the frozen sucker as a new line would not adversely affect their primary ice cream business.

Although Citrus would deny that the stick idea was patentable, its president felt that it would be in the best interests of Citrus and their licensees to acknowledge the Burt patent and began negotiations with Burt for a license allowing Citrus the exclusive rights to "make, use, and sell molds, appliances and materials for the manufacture and sale of frozen suckers." Twice, on March 26 and May 1, 1925, agreements were prepared, but neither was signed by both parties.

In his suit against Citrus filed on August 24, 1925, Burt charged both the alleged infringement of his patent and unfair competition in trade. He claimed that Citrus had wanted a Burt-issued license because "the Burt patent [is] so broad that it is impossible to make the suckers without infringing the same."

Eventually the suit was dismissed at Burt's request in 1926, although it was the intent of Citrus to pursue the case to trial to determine the validity and scope of the Burt patent and its applicability to any frozen confection on a stick.

"The Epsicle"

The birth of the Popsicle belongs in legends. As a young man, Frank W. Epperson left a syrupy drink with a stirring stick out on a cold night in California in 1905. By the next morning, it had frozen to the stick. In the early 1920s, he began to recreate his accidental invention. He originally called it the "Epsicle" but his children called it "Pop's Sicle." Convinced that a wider market existed, he collaborated with employees of the Loew Movie Company to form the original Popsicle Company in 1923. This company introduced the product to concessionaires at amusement parks and beaches in April or May of 1923. The Popsicle achieved immediate success, and in one day, one stand at Coney Island sold as many as 8,000 Popsicles.

A new Popsicle Corporation of the United States was founded in 1924. It purchased the operating rights from the Loew's group and reported sales of 6.5 million Popsicles that year. On June 11, 1924, Epperson filed for a patent on the Popsicle process, which was granted two months later. He immediately sold all of his patent rights to the Popsicle Corporation on September 8, 1924, and turned his attention to other matters.

The Popsicle Corporation embarked upon major advertising campaigns for the 1925 season in trade journals and other publications, emphasizing its product as a "frozen lolly pop" or "A Drink on a Stick." Popsicle manufactured the appropriate syrups, sticks, wrappers, and molds for the confection, which they sold to their licensees.

In 1925 the Joe Lowe Corporation approached the Popsicle Corporation with an offer to become their exclusive sales agent. Founded in 1909 by Joe Lowe and Louis Price in New York as a supplier of ingredients for bakeries and confectioners, it was, Lowe believed, "probably the largest purveyor of ingredient supplies to the Ice Cream Industry in this country." After witnessing the popular growth of the "Frozen Sucker" sponsored by the Citrus Products Company, and knowing that Popsicle owned a patent, he felt secure in a lucrative association with Popsicle. An agreement was reached in August 1925 under which Popsicle utilized Joe Lowe's existing widespread marketing contacts.

The Popsicle Patent Battles, 1924–1929

In the fall of 1924, Popsicle instituted suits against the Kold Kake Company in New Jersey and M-B Ise Kream Company in Texas for violation of its patent. In the first suit, the court upheld the Epperson patent on November 20, 1924, providing Popsicle with its first successful legal defense of its product.

On May 21, 1925, the Popsicle Corporation filed suit against six Philadelphians, all of whom admitted guilt in infringing upon Popsicle's rights. Less than a month later, on June 10, 1925, Popsicle sued the Horn Ice Cream Company of Baltimore, Maryland. During the same period, Popsicle sued Robert Bayer of New York and received a consent decree affirming the validity of the Epperson patent on September 18, 1925.

The M-B Ise Kream and Horn Ice Cream suits were actually battles between the Popsicle Corporation and Citrus Products Company, both of whom were marketing similar products in 1924–1925. Citrus had admitted in its Illinois defense against Harry B. Burt that the M-B Company developed the "Frozen Sucker" around June 1924, after Popsicle had been founded and Epperson applied for his patent.

Stephen Philbin, the attorney for the Horn Ice Cream Company (and for Citrus Products), stated that the U.S. Patent Office was investigating similarities between the Epperson patent and another pending patent. The defendants denied that Epperson had actually invented the idea of a frozen sucker, charging that Epperson's creation, or some variation of it, had been used by at least 10 or more individuals or companies (including Harry B. Burt), before Epperson's application.

Morris Hirsch, the attorney for the Popsicle Corporation, argued that all of the statements between the two parties "show that Epperson's date of invention was January, 1905" and the other patent petitioner did not conceive of his product until March 30, 1922. The two parties settled the case out of court, and it was dismissed on July 16, 1926.

On February 26, 1925, Burt filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York against the Popsicle Corporation for infringement of his rights. Burt apparently favored Citrus Products over Popsicle as a licensee for frozen ice suckers, for he had entered into negotiations with Citrus about this time. After those negotiations failed, Burt and the Popsicle Corporation agreed to a license arrangement on October 13, 1925. In it the parties agreed to drop all lawsuits against each other, and Burt granted Popsicle the exclusive right to manufacture and market frozen suckers or Popsicles throughout most of the United States and Canada.

The third section of the agreement divided the market between Burt and Popsicle. In this section, the parties agreed that "this license applies only to Popsicles or frozen suckers, comprising a mass of flavored syrup, water ice or sherbet frozen on a stick, and that Licensor reserves unto himself all other rights . . . including the right to make frozen suckers from ice cream, frozen custard or the like." Similarly, both parties agreed to respect the patent rights of each other and that a cylindrical form of the frozen sucker was reserved to Popsicle while rectangular forms would be Burt's.

Citrus found itself unprotected by any patent after the Burt-Popsicle agreement. It continued to deny the validity of both the Burt and Epperson patents and sued Popsicle on May 19, 1926, in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware. Among its claims was that Burt and Popsicle both "have deliberately and intentionally refrained from presenting to the courts for decision the issue of whether either of said patents validly cover the manufacture and sale of frozen suckers." Citing both the M-B Ise Kream and the Horn Ice Cream cases, in which it had been a silent partner, Citrus accused Burt and Popsicle of instituting suits in various federal courts but not prosecuting them fully. This suit never came to trial either, as Citrus and Popsicle sought a dismissal on June 29, 1927.

In April 1927, Citrus, Joe Lowe, and Popsicle signed an agreement by which Citrus and Joe Lowe became co-agents for Popsicle. The companies advertised their products in 1927 and 1928 under the joint name of "Popsicles-Frozen Suckers" in order "not to lose the prestige established by Frozen Suckers during the previous seasons." Popsicle dropped the "Frozen Sucker" beginning in 1929.

Harry Burt died in 1926, leaving his widow, Cora Burt, to continue the operation of the company. After two years, she sold all of the Good Humor patents and business to the Midland Food Products Company, reserving only the license agreement with Popsicle. Midland then changed its name to the Good Humor Corporation. Protecting her interests with Popsicle, she joined them on several suits during the following two years to protect this license and the patent processes. These included suits in the Southern District of New York in 1928 and the Eastern District of Missouri in 1929, and at least two others in the Southern District of California.

Good Humor v. Popsicle

The Depression caused problems with the 10-cent ice cream market but not with the cheaper ices. The Popsicle Corporation advertised itself as "Depression Proof" and stated that its sales had doubled between 1930 and 1931. "People who could not afford dimes, quarters and halves for ice cream gladly bought Popsicles at a nickel each for children, family and friends," according to a February 1931 advertisement. Popsicle sold more than 200 million units in 1931.

The division of the frozen sucker market between Good Humor and Popsicle seemed relatively secure and understood by both parties. As related by Clara Burt Roller, "The Popsicles did not compete with Good Humor ice cream confections . . . because, first, the 'Good Humor' was an ice cream and Popsicles were ices of different flavors."

But Popsicle was under pressure by some of its licensees to provide a cheap ice cream product after the drop in dairy prices made such a product attractive. In the fall of 1931, Popsicle, Lowe, and Citrus approached Good Humor with an offer to create such an item and to refine the division of products in the 1925 agreement. Popsicle wanted to have the rights to manufacture all products containing less than 4.5-percent butter fat as a form of sherbet. Those above that limit would fall into the category of "ice cream, ice custards, and the like" and would be produced by Good Humor. The type of product that Popsicle wished to create would be considered an "ice milk" or "light ice cream" today.

The 1925 licensing agreement between Popsicle and Burt allowed Popsicle to make "sherbet," but at that time the industry did not have a set definition of sherbet. Popsicle felt secure that they could make any product that was not regulated as ice cream. Good Humor did not want competition from Popsicle in the manufacture of any milk-based frozen sweets, claiming that the 1925 license agreement prohibited such a product.

One reason why Good Humor did not want to relinquish this part of the market was its introduction of a new product known as the "Cheerio" bar—a 5-cent version of the 10-cent Good Humor bar—in the fall of 1931.

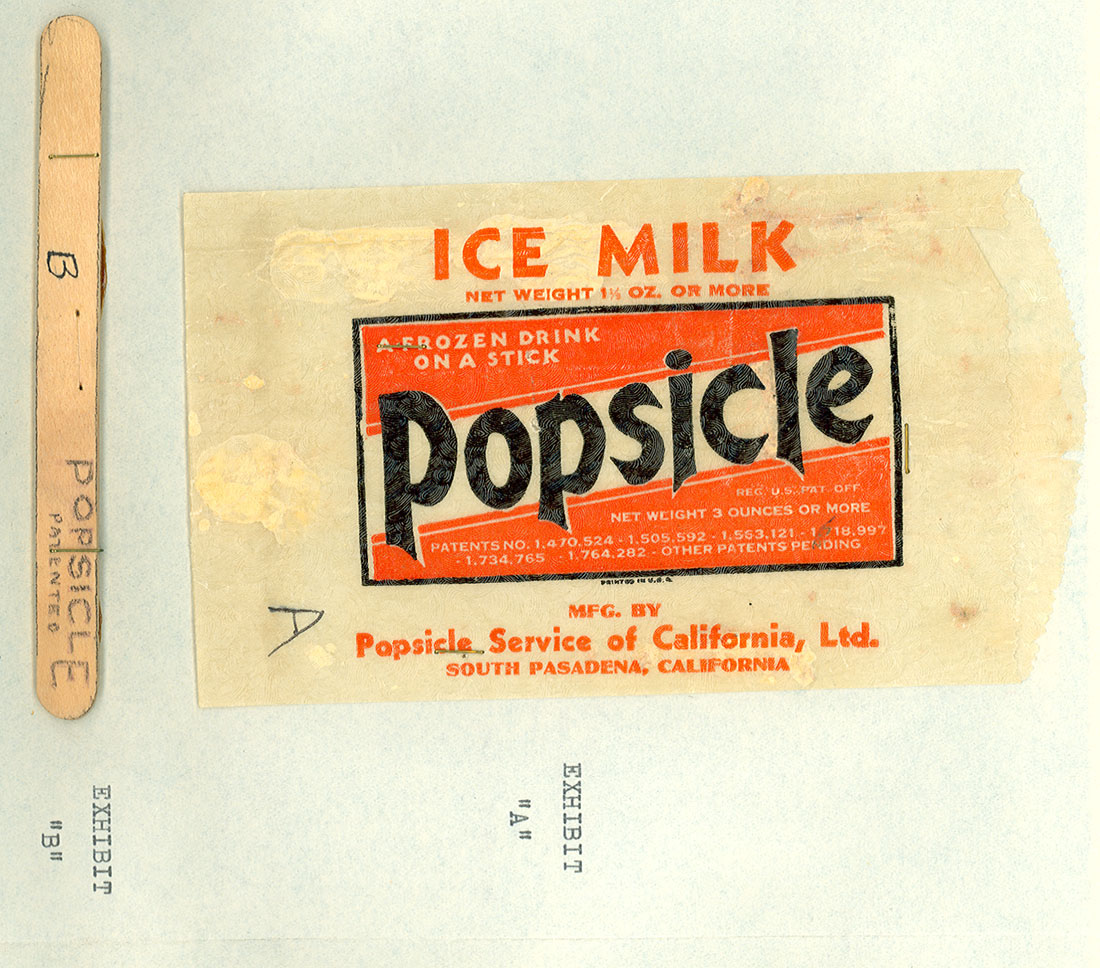

During the winter of 1931–1932, Popsicle authorized its companies to begin producing the "Milk Popsicle," a chocolate-covered confection that had 4.48-percent butter fat in its composition and used a keystone-shape design. R. W. McConnochie, vice president of the Frozen Confections, Inc., a Good Humor subsidiary, protested that "the Milk Popsicle is purchased . . . in the belief that it is ice cream and afford to him a much larger quantity of such an edible product than does the Cheerio."

On February 20, 1932, Good Humor filed suit in the U.S. District Court in Delaware against the Popsicle and Joe Lowe corporations claiming infringements of the 1925 agreement because Popsicle was (1) making a milk-base product and (2) using a rectangular design.

Good Humor's president, Thomas J. Brimer, referred to various Popsicle advertisements from 1925 to 1930 in which the latter company promoted its products as water-based confections. Among these was Popsicle's own questionnaire to its sales agents relating to potential infringements: "Anyone putting out a frozen water ice on a stick and making from anything other than Popsicle Flavors or calling it by any name other than Popsicle is an infringer."

Judge John J. Nields read all of the affidavits and heard the testimony in the case. He recognized that Burt and the Popsicle Corporation intended to divide the frozen sucker field. He determined the main reason for the lawsuit: "What was the division? That is the question in dispute."

Both sides attempted to define the composition of a sherbet using dictionary terms and the belief of ice cream manufacturers of the times. Among Good Humor's definitions was that of a "flavored water ice." Popsicle countered by stating that its new "Milk Popsicle" was a sherbet in the understanding of the ice cream industry. From the manufacturer's viewpoint, an ice "is a mixture of water, sugar and flavor, while a sherbet is the same with the exception that the water is replaced with a milk product or, in modern practice, ice cream mix."

In his rebuttal of Popsicle's arguments, R. W. McConnochie received 32 responses to his inquiry to state regulators regarding the status of the Milk Popsicle formula relative to their ice cream standards. The majority of them declared this formula to be prohibited as an ice cream in their states and that any product made from the formula clearly had to be labeled as an "imitation ice cream," "frozen custard," "milk sherbet," or "ice milk." Only the Milk Popsicles manufactured in California were labeled as Ice Milk Popsicles.

After understanding all views in the case, Judge Nields was satisfied that term "sherbet" in the agreement was strictly to mean a "water sherbet," and indeed the two companies co-existed peaceably for about six years between 1925 and 1931 without challenging the understandings of their division. Having become satisfied that the Milk Popsicle was a violation upon the Good Humor rights, he issued an injunction against the product on May 27, 1932. He did not make any ruling upon the shape of the confection, except to say that the Milk Popsicle and the Cheerio or Good Humor bars were alike in appearance, texture, and taste.

Both sides appealed his decision to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 1933. Popsicle appealed his rulings on sherbet composition, and Good Humor appealed on the absence of any definitive ruling regarding the Milk Popsicle's rectangular shape. The court of appeals confirmed Nields's decision relating to the division of the marketplace because the district court was not asked to define "sherbet" but only the 1925 division of the marketplace. It also confirmed that Judge Nields was concerned only with whether the Milk Popsicle was a permitted product under the agreement and not with the shape of the Popsicle.

The decisions by both the district court and the Third Circuit Court of Appeals found Popsicle and Joe Lowe, Incorporated, violating the 1925 agreement. Before the opinion was rendered, however, Good Humor and Popsicle concluded negotiations for a new agreement, signed on April 7, 1933. They allowed their respective appeals to be decided by the courts, but any opinion rendered by the courts would be held in abeyance during the lifetime of their new agreement.

The Frozen Sucker War had come to a peaceful end. Popsicle was allowed to continue manufacturing water ices in a keystone design and later developed new forms for its creation, including the familiar double-stick Popsicle. Ironically, today both the Good Humor Bar and the Popsicle are owned and manufactured by the same company, Good Humor-Breyers Ice Cream.

Note on Sources

There are many stories about American life and culture that appear in the records of the federal court system. This article was intended to concentrate on one specific case, but it soon became evident that papers filed in various suits brought before the district court judges throughout the country recorded the entire early history of Good Humor and Popsicle. The case files in the Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21, are held at the regional archives of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The author wishes to thank staff in other regional archives for their assistance in locating various court cases: John Celardo (New York), Mary Evelyn Tomlin (Atlanta), Glenn Longacre (Chicago), Timothy Rives (Kansas City), Barbara Rust (Fort Worth), David Piff (San Bruno), and Lisa Gezelter (Laguna Niguel).

These cases were heard before a number of federal courts, whose records are held in various regional archives. Among the cases consulted for this article are:

NARA–Mid Atlantic Region (Philadelphia)

U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware: Equity Case # 953 (Good Humor Corporation of America v. The Popsicle Corporation of the United States, and Joe Lowe Corporation); Equity Case # 603, Citrus Products Company v. The Popsicle Corporation of the United States.

U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland: Equity Case # 880 (The Popsicle Corporation v. Horn Ice Cream Co., Inc.).

United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania: Equity Cases # 3341 (The Popsicle Corporation v. William Bellmann), # 3345 (Max Rudolph, defendant), # 3347 (Max Zimmerman, defendant), # 3349 (Philip Rubin, defendant), # 3351 (Morris Adelman, defendant), and # 3353 (Morris Ostrow, defendant).

NARA–Northeast Region (New York)

United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York: Equity Case # 2022 (The Popsicle Corporation v. Robert Bayer)

United States District Court for the Southern District of New York: Equity Case # 31-265 (Harry B. Burt v. Popsicle Corporation of the United States, Inc.); Equity Case # 46-58 (The Popsicle Corporation, The Popsicle Corporation of the United States, and Cora W. Burt v. Isadore Weiss (doing business as Goody Frozen Products Co.).

NARA–Great Lakes Region (Chicago)

U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division: Equity Case # 5064, (Harry B. Burt v. Citrus Products Company and Eric Scudder).

NARA–Central Plains Region (Kansas City)

U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri: Equity Case # 8756 (The Popsicle Corporation, The Popsicle Corporation of the United States, and Cora W. Burt v. Dolores C. Madison and Lillian Hoagland.)

NARA–Southwest Region (Fort Worth)

U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas: Equity Case # 3179-437 (Cora Burt v. Have-A-Heart Ice Cream Company).

NARA–Pacific Region (Laguna Niguel)

U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California, Central Division (Los Angeles): Equity Case # S-23-M (Cora W. Burt Roller v. K. Kirk); Equity Case # R-77-J (National Popsicle Corporation, The Popsicle Corporation of the United States, and Cora W. B. Roller v. Icyclaire, Inc., and Joseph Valente).

Additional cases are known to have been filed in various courts in Alabama, California, Florida, New Jersey, and New York.

U.S. Patent Office, Patent Numbers 1,404,539, 1,470,524, 1,470,525, and 1,505,592.

Candy and Ice Cream for the Candy Store, Fountain and Tea Room, Volumes 33 and 34, 1922–1923.

Anne Cooper Funderburg, Chocolate, Strawberry and Vanilla: A History of American Ice Cream (Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1995)

Jefferson Moak is an archivist in the National Archives and Records Administration–Mid Atlantic Region (Philadelphia) and has written extensively on Philadelphia history, including Atlases of Pennsylvania (1976), Philadelphia Street Name Changes (1997), and Architectural Research in Philadelphia (2002).