Ike's Interstates at 50

Anniversary of the Highway System Recalls Eisenhower's Role as Catalyst

Summer 2006, Vol. 38, No. 2

By David A. Pfeiffer

In the summer of 1919, just months after the end of World War I, an expedition of 81 Army vehicles—a truck convoy—set out from Washington, D.C., for a trip across the country to San Francisco.

The convoy's purpose was to road-test various Army vehicles and to see how easy or how difficult it would be to move an entire army across the North American continent. The convoy assumed wartime conditions—damage or destruction to railroad facilities, bridges, tunnels, and the like—and imposed self-sufficiency on itself.

Averaging about 6 miles an hour, or 58 miles a day, the trucks snaked their way from Washington, up to Pennsylvania and into Ohio, then due west across the agricultural Midwest, the Rockies, and into California. Generally, it followed the "Lincoln Highway," later known as U.S. 30, arriving in San Francisco 62 days and 3,251 miles later.

The convoy involved 24 Army officers and 258 enlisted men. One of those officers, a young lieutenant colonel, went along as a Tank Corps observer "partly for a lark and partly to learn," he wrote decades later. "We were not sure it could be accomplished at all. Nothing of the sort had ever been attempted."

The convoy made a lasting impression on the young officer and stoked in him an interest in good roads that would last for decades.

A generation later, during World War II, Dwight D. Eisenhower was still thinking about good roads as Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, where he oversaw the invasion of Western Europe and the defeat of the Nazi army, which was able to move quickly on the autobahns running throughout Germany.

Later, as President of the United States, Eisenhower cited the 1919 convoy and his World War II experiences to persuade Congress to enact the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, creating what is now known as the interstate highway system, which is observing its 50th anniversary this year.

"The old convoy had started me thinking about good, two-lane highways," he wrote years later in his popular memoir, At Ease, "but Germany had made me see the wisdom of broader ribbons across the land."

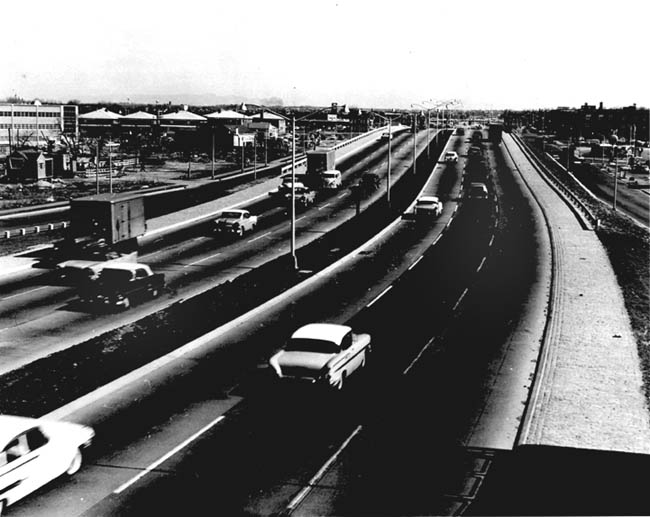

The interstate system now comprises 46,876 miles. The completion of the system, at a cost of $129 billion, was a cooperative federal-state undertaking. Each state transportation department managed its own program for location, design, right-of-way acquisition, and construction. The states also were responsible for the ownership and maintenance of the system, and in 1981, they began receiving federal funds for maintenance.

Congress provided revenues from the federal gasoline tax to provide 90 percent of the cost of the construction of the interstates with the states picking up the remaining 10 percent. The technical standards for the highways were highly regulated—lanes had to be 12 feet wide and shoulders 10 feet wide, the bridges had to have 14 feet of clearance, grades had to be less than 30 percent, and the highway had to be designed for travel at 70 miles an hour. The most notable attribute of the system is the limited access concept. The 42,000-mile system only has approximately 16,000 interchanges.

The interstate system has had an enormous and lasting impact on the social and economic fabric of the nation, even as it has provided, as Eisenhower hoped, a system of highways that might be needed to move materiel and troops in time of war.

Eisenhower Remembers the Rough Roads

All this might never have happened if Lieutenant Colonel Eisenhower had not been involved with the 1919 transcontinental convoy, for the history of the interstate highway system certainly begins with this event.

Eisenhower, along with the other observers, endured rough conditions on the trip. Half the distance, particularly west of the Mississippi River, was over dirt roads, wheel paths, desert sands and mountain trails. More than 230 recorded road accidents occurred, as the heavy trucks, driven mostly by inexperienced drivers, sank in quicksand or mud, ran off the road, or overturned. Other problems included inadequate bridges; limited sleep; lack of food, shelter, and bathing facilities; and even the lack of drinking water.

In spite of all this, the results of the transcontinental exercise provided much valuable information about the operation and maintenance of a motor truck convoy as well as the feasibility of moving a large military force by road across the continent under simulated wartime conditions.

Consequently, in the opinion of the ordnance observer, the convoy was a successful operation, not only militarily but also from a public relations point of view.

"All along the route, great interest in the Good Roads Movement was aroused by the passage of the convoy," reported E. R. Jackson, the ordnance observer in his "Report on the First Transcontinental Motor Convoy." "However, the officers of the convoy were thoroughly convinced that all transcontinental highways should be constructed and maintained by the Federal Government" because some rural states could not afford the funds for road building.

Eisenhower, in his report on the expedition, agreed with some of these points but had observations of his own. "Extended trips by trucks through the middle western part of the United States are impracticable until the roads are improved," he said, "and then only a light truck should be used on long hauls." On the other hand, he observed that in the eastern part of the country, the roads were much better, allowing a light truck to travel 100 miles a day.

But the convoy did more than just indicate what the Army needed to do to improve its mobility. Along the way, its arrival in cities and towns throughout the nation's Midwest and West was a major event. Some 3,250,000 people in 350 communities turned out to see the latest military equipment and listen to patriotic speeches. And the expedition stirred interest in road building.

Federal Aid to Highways Proved a Divisive Issue

The increased public interest in roads also raised the issue of federal aid to highways.

This early in the debate, there were many critics of federal aid to highways. Thomas M. McDonald, who became chief of the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) in 1919, "appreciated the need for a connected system of interstate highways, but he did not believe that a separate national system under a federal commission was the way to achieve it," according to a history of America's highways, A History of the Federal-Aid Program. He also questioned the assumption that long-distance highways were necessary for national defense, saying that what was needed was a system of roads connecting military installations.

Correspondingly, McDonald believed that the state highway departments should be strengthened. The Federal Highway Act of 1921 reflected this view, strengthening the state highway department's control of the highway system, particularly in maintenance. This act temporarily quieted demands for interstate highways under federal control.

By the late 1930s, however, more Americans owned automobiles, and highways were getting more congested. Public sentiment for federal control of the construction of transcontinental superhighways was increasing.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, seeking to pull the nation out of the Great Depression, saw a network of toll superhighways as a way to provide new jobs for the unemployed. At the time, he thought a system of three east-west and three north-south routes would be enough.

At the same time, Congress also got into the act. The Federal Highway Act of 1938 directed the Bureau of Public Roads to study the feasibility of a six-route toll highway network.

In its 1939 report, "Toll Roads and Free Roads," the bureau concluded that with some exceptions, the "amount of transcontinental traffic was insufficient to support a network of toll superhighways." The report recommended a 43,000-mile non-toll highway network in its "Master Plan for Free Highway Development." This proposal called for highways to follow existing roads whenever possible, have more than two lanes of traffic available if traffic required it, and be limited-access in high-traffic areas. In the large cities, the proposal allowed for above- or below-grade intersections and limited-access belt lines surrounding the central business district to permit traffic to bypass the inner city and to link intercity expressways.

Roosevelt enthusiastically approved the report and sent it to Congress on April 27, 1939, saying that instead of imposing user tolls, the cost of highways could be recovered by selling off federal land along the right-of-way to homebuilders and others. Critics in and out of Congress condemned this suggestion as a "socialistic scheme to transfer the cost of providing deluxe highways from those most benefited to the already heavily burdened landowner." Overall, however, reaction was favorable within the highway community.

With the outbreak of World War II, the need for a national system of highway dropped in priority. However, toll roads were being built by the states. When the Pennsylvania Turnpike (now I-76 and I-70) opened to traffic on October 1, 1940, it was the prototype of the modern, high-speed interstate highway. In New York and Connecticut, the Hutchinson River Parkway and the Merritt Parkway, both toll roads, proved highly profitable. Other freeways and toll roads were incorporated into the interstate system at the time of its creation in 1956.

As the war began to turn in the Allies' favor, attention refocused on the federal highway program. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944, enacted after nine months of intense negotiations in Congress, was the largest highway bill in history, even though it did not meet the expectations of the administration and the states. Its net effect was to maintain the status quo. However, it did authorize a limited 40,000-mile National System of Interstate Highways, to be selected by the state highway departments, to connect the major metropolitan areas and to serve the national defense. But the act was passed without any provision for construction funds because Congress rejected the President's suggestion for raising money by selling off excess rights-of-way.

The Public Roads Administration (PRA), the successor agency to the Bureau of Public Roads, was responsible for formulating an interstate highway system based on the states' recommendations. On August 2, 1947, after a year of negotiations, a 37,681-mile system, including urban thoroughfares and circumferentials, was approved.

Also, design standards for the interstate system were developed by the PRA, along with the American Association of State Highway Officials. These standards, approved August 1, 1945, "did not call for a uniform design for the entire system, but rather for uniformity where conditions such as traffic, population density, topography, and other factors were similar." Most highways would have at least four lanes with limited access, but lesser highways (two lanes with at-grade intersections) would be permitted if there were low traffic volumes.

Construction of the system was slow. Many states did not wish to divert federal-aid funds from local needs, others complained that standards were too high, and still others determined that toll roads were needed because federal funding was so low. And in 1950, the Korean War distracted policymakers.

Adequate federal funding for the interstate system was still not forthcoming. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1952 authorized $25 million for the system on a 50-50 matching basis. These were the first appropriated funds actually dedicated to the system, even though it was only a "token amount."

Eisenhower Makes Interstates a Top Presidential Priority

But 1952 also brought a presidential election, which swept into office the same man who had been appalled by the conditions of roads in 1919 and impressed by the German autobahns in 1944.

One of Eisenhower's top priorities upon becoming President was to secure legislation for an interstate highway system. Since his first year in office, 1953, was dominated by the Korean war, he did not raise the highway issue until 1954.

That year, Congress passed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1954, which authorized $175 million for an interstate system, to be distributed on a 60-40 federal-state basis. Signing it, however, Eisenhower called it merely "one effective forward step." More, he believed, was needed.

In July 1954, he brought up the idea again, and a conference of state governors at Lake George, New York, provided the setting. Eisenhower was unable to attend because of his sister-in-law's death, so he sent Vice President Richard Nixon to deliver his message to the governors.

The legislation he had signed a few months earlier, he told them, was a "good start," but a more comprehensive interstate network of highways was needed to reduce the number of highway deaths and injuries, cut down on delays because of detours and traffic jams, reduce the amount of highway-related litigation, and allow more efficient truck transportation of goods. And, he added, the system was needed to address "the appalling inadequacies to meet the demands of catastrophe or defense, should an atomic war come." Eisenhower also proposed a self-liquidating financing system that would avoid debt.

The proposal excited the governors, and the President named a special panel to study the problem. Headed by retired Gen. Lucius D. Clay, it gave its report to the President early in 1955, and he forwarded it to Congress. The panel called for a Federal Highway Corporation that would issue bonds to build the system and for a gas tax to be used to retire the bonds over three decades. The cost of building an interstate system of highways would be about $27 billion, it said, with $25 billion of it coming from the issuance of the bonds.

Members of Congress, however, had their own ideas. Legislation calling for an interstate system with 90-percent federal funding was defeated even after intense efforts to strike a compromise that would have wide appeal.

In his State of the Union speech in January 1956, Eisenhower tried again. And the Bureau of Public Roads issued a book, General Location of National System of Interstate Highways, that showed where interstates would be located in and around the nation's largest metropolitan areas. Opponents to the funding mechanism in 1955 were now agreeing to some increases in the gas tax.

With Eisenhower standing firm for legislation to create the interstate system, Congress went back to work on it, and finally produced legislation that called for 90 percent federal funding, with money coming from a Highway Trust Fund that received the revenue from the federal gasoline tax.

The final version also reflected a compromise on how the funds would be apportioned among the states, and it contained provisions on uniform design standards, inclusion of existing toll roads, and the wage rate to be paid on these federal construction projects. It also permitted use of federal funds to purchase the rights-of-way for the roads and allowed two-lane segments, although later legislation required all parts of the system to be four-lane, limited-access highways.

On June 26, 1956, both the Senate and the House gave final approval to the compromise version and sent it to Eisenhower, who was in Walter Reed Army Hospital with an intestinal ailment. There, he signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 privately, without ceremony, on June 29, 1956.

Interstates Transform America, Spur Mobility, Increase Commerce

Today's interstate highway system—first envisioned in the 1930s, then enacted two decades later after Eisenhower put his considerable prestige behind it, and now observing its 50th anniversary—has had a tremendous impact on the country.

While created in part to help defend the nation in the event of an emergency, the interstates, with limited access and many lanes, have also spurred and speeded the development of commerce throughout the country and abroad. Trucks move quickly from one region to another, transporting everything from durable goods and mail to fresh produce and the latest fashions.

And they have increased the mobility of all Americans, allowing them to move out of the cities and establish homes in a growing suburbia even farther from their workplaces and to travel quickly from one region to another for vacation and business.

But the interstates have also increased congestion, smog, and automobile dependency. The shift to the increasingly outward bound suburbs has caused a drop in population densities of urban areas, and the ease of long-distance travel on high-speed, limited-access highways has contributed to the decline of mass transit, such as rail and bus.

During the decades of its construction, the interstate highway system was the largest public works project in American history—pumping billions into the nation's economy all over the country. Today, it still has an economic impact because of the continued maintenance and repairs needed for the roadways.

In 1990, on the centennial of Eisenhower's birth, President George H.W. Bush redesignated the interstate system as the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. One of the system's longest roadways, Interstate 80, would be quite familiar to Eisenhower today.

It starts just across the Hudson River from New York City, then goes through New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and into Ohio, where it then follows generally the route of the 1919 Army convoy to San Francisco that stoked an interest in roads for the young Army officer from Kansas.

David A. Pfeiffer is an archivist with the Civilian Records Staff, Textual Archives Services Division, of the National Archives at College Park. He specializes in transportation records and has published articles and given numerous presentations concerning railroad records in the National Archives. He is the author of Records Relating to North American Railroads, Reference Information Paper #91 and of the award-winning article "Bridging the Mississippi," in the Summer 2004 Prologue.

Note on Sources

Secondary sources used in this article concerning President Eisenhower and the 1919 convoy and his World War II experiences with the German autobahns include Dwight D. Eisenhower, At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends (New York: Doubleday, 1967) and Stephen E. Ambrose, Eisenhower, 2 volumes (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984). Sources consulted concerning the history of the interstate highway system include Mark H. Rose, Interstate: Express Highway Politics, 1939–1989 (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1979); Dan McNichol, The Roads that Built America (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2003); America's Highways, 1776–1976: A History of the Federal-Aid Program (Washington, DC, Federal Highway Administration, 1976); and Richard F. Weingroff, "Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956: Creating the Interstate System."

There are two main sites on the Internet for information on the interstate highway system. One is the Federal Highway Administration 50th anniversary site. Another is the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library. These sites have several articles and images of records relating to the history of the Interstate Highway System.

Primary sources used in this article for information on the 1919 convoy include "The Report on First Transcontinental Motor Convoy" by E. R. Jackson, 1st Lieutenant, Ordnance Department, in the Manufacturing, Tank, Service Tractor, and Trailer Division (OMT), Decimal Correspondence Files, 1919–1920 (Records of the Office of the Chief of Ordnance, Record Group [RG] 156). This report includes reports on the vehicles on the convoy, a daily log of the trip, and copies of the telegrams sent by the ordnance observer. The Eisenhower report on the convoy as an observer for the Tank Corps is located on the Eisenhower Library web site.

The textual, cartographic, and photographic records of the Bureau of Public Roads (RG 30) are located in the National Archives at College Park. Textual records used as background for this article include correspondence concerning the construction of individual interstate highways in the General Correspondence, 1912–1965. Also, the Reports About the Interstate Highway System include the Report to the President on Interregional Highways, 1941, and other reports on interregional highways such as the analysis of physical conditions and traffic density, recommended design standards, a proposal on financing and administrative matters, and a study on national multilane highways. In addition, the Papers and Speeches of Harold Hilts (deputy commissioner of the Public Roads Administration) include a speech titled "Cooperation in Essential in Building a National System of Interregional Highways."

The photographic records include the prints of the Bureau of Public Roads (RG 30), Highway Transport, 1960–1963, Interstate Highways (boxes 363–367). The Cartographic and Architectural Reference Staff has custody of the famous Roosevelt map with FDR's blue pencil annotation of a U.S. highway map showing the proposed lines of a future interstate highway system. Also, in RG 30, Series 5, Maps of Highway Systems (Interstate and Defense Highways) contains several BPR maps on the National System of Interstate Highways, dated 1947.

The Center for Legislative Archives of the National Archives has custody of the records of the various committees of the House of Representatives and the Senate relating to the legislative history of the 1956 act.