1798 Federal Direct Tax Records for Connecticut

Spring 2007, Vol. 39, No. 1

A Discovery:

1798 Federal Direct Tax Records for Connecticut

By Judith Green Watson

© 2007 by Judith Green Watson

In 1798, tensions between the United States and France had risen to such a level that many thought war was imminent. To fund America's military buildup, Congress enacted a $2 million direct tax in July 1798. In each state, officials created forms and set out to value real property, enumerate slaves, and collect their assigned portion of the tax.

The voluminous records created for the 1798 federal direct tax—valuation, enumeration, and tax collection lists—have long been a treasure trove for researchers in a wide variety of fields. Historians, economists, geographers, and genealogists as well as those interested in historic preservation, material culture, slavery, and women's studies all have gleaned valuable information about 18th-century life. Unfortunately, relatively few are known to exist today. Several years ago, an important addition to this body of records was made at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)–Northeast Region (Boston).

While processing customs records for the Port of New Haven in 2004, archivist Michael T. Moore located more than 900 "Particular List" valuation slips for the towns of Kent and Warren in Litchfield County, Connecticut. These slips describe dwelling houses and other real property owned as of October 1, 1798—details available from no other source. Moore also found the tax collection list, or rate bill, that identified how much tax each person owed, separately for dwelling houses and lands, for the assessment district that these two towns composed. Late in 2005, Moore found more than 200 additional Particular List slips for the town of Warren.

This is a significant find for the National Archives because the only other valuation and enumeration lists from the 1798 federal direct tax that are in its holdings are for Pennsylvania. Because these Kent and Warren records contain a total inventory of all real property, they provide a richly textured picture of life in 1798. Moreover, these records significantly add to the historical record of the 1798 direct tax in Connecticut; this is the only known instance in which essentially all the Particular List slips and the tax collection list for any of Connecticut's 67 assessment districts have survived.

How the Tax Operated

Each of the 16 states was allocated its share of the national levy of $2 million. This quota was based upon population, with slaves counting as three-fifths of a person for allocation purposes. Only real property and slaves were taxed, and no property was taxed if it was permanently exempt from taxation by state law.

The 1798 tax had three parts:

- Dwelling houses valued at more than $100 were taxed based upon the value, with highly progressive tax rates that ranged from two-tenths of 1 percent of the value up to 1 percent of the value.

- Slaveowners were taxed 50 cents for each slave between the ages of 12 and 50 who was not precluded from working as a result of permanent illness or disability.

- All other real property—called simply "land"—which included dwelling houses valued at $100 or less, was taxed at a fixed percentage of the value. Each state's land tax rate was computed separately, as a residual after the amount of tax derived from the first two categories was subtracted from the quota.

Eleven new forms were created specifically to implement the tax. The administration of the tax was divided into valuation and enumeration versus collection. In each state, a presidentially appointed Board of Commissioners (U.S. Commission for the Valuation of Lands and Dwelling Houses, and the Enumeration of Slaves) was responsible for the valuation of real property and the enumeration of slaves. Officials of the United States Treasury collected the tax.

The Kent and Warren Particular List Slips

Two types of Particular List slips were used in Kent and Warren. Details about dwelling houses were recorded on one slip, and all other real property was described on another. Because there were no slaves in Kent and Warren as of October 1, 1798, no Particular List slips were created that would have enumerated slaves.

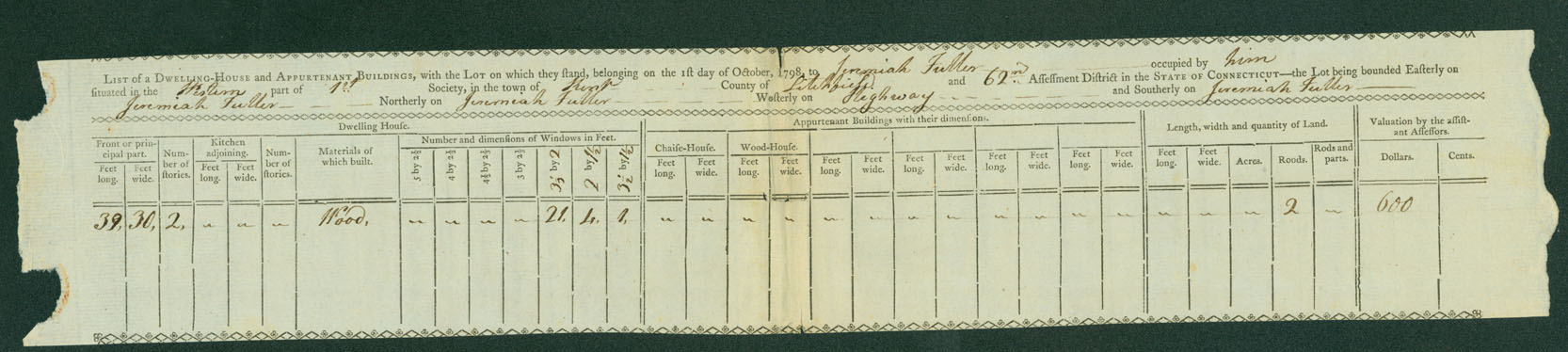

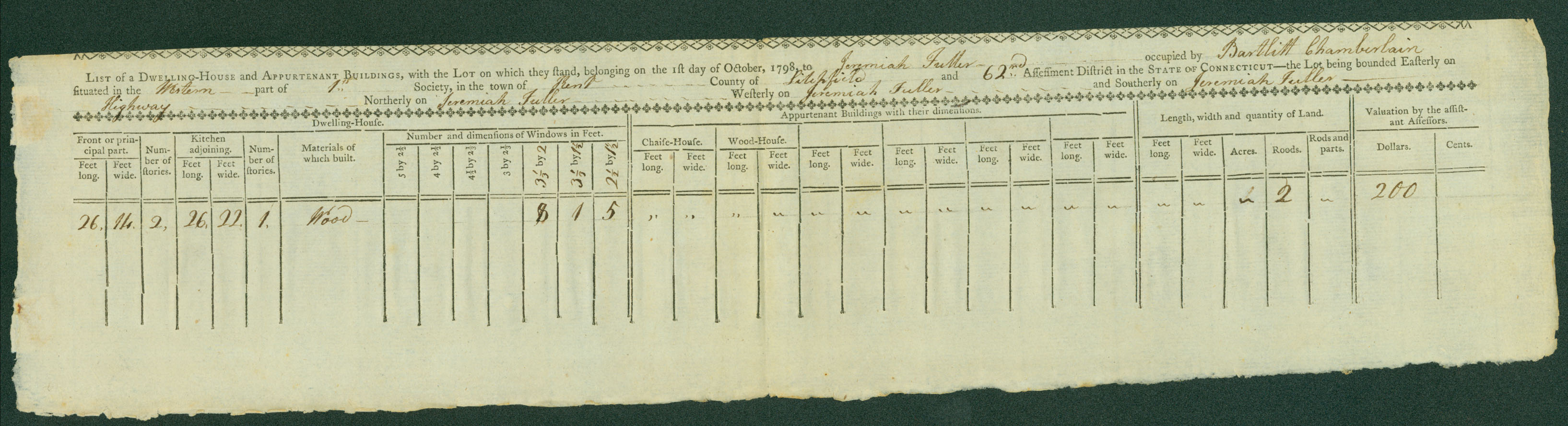

These slips, about 3 inches high by 16 inches wide, differ somewhat from the forms suggested by then secretary of the treasury, Oliver Wolcott, Jr. Although it was a federal tax, each state was allowed to alter Wolcott's forms to meet its unique conditions.

In Connecticut, owners submitted a Particular List slip for each dwelling house, no matter what the value. This slip, headed "List of a Dwelling-House and Appurtenant Buildings, with the Lot on which they stand . . . ," identified both the owner and occupant, and if the owner was a nonresident of the town, included his or her town of residence. It also identified the name of the ecclesiastical society and the part of the society in which the house was located. Owners provided a description of each house, including the dimensions; number of stories; whether there was an adjoining kitchen, and if so, its dimensions and number of stories; materials of construction; number and size of windows; the number, type, and dimensions of out-houses appurtenant to the dwelling house, such as chaise-houses or wood-houses; the names of the bounding property owners; and the size of the lot on which the house was situated, up to a maximum of two acres. The assistant assessor used the details to value the property, and he posted his valuation to the slip.

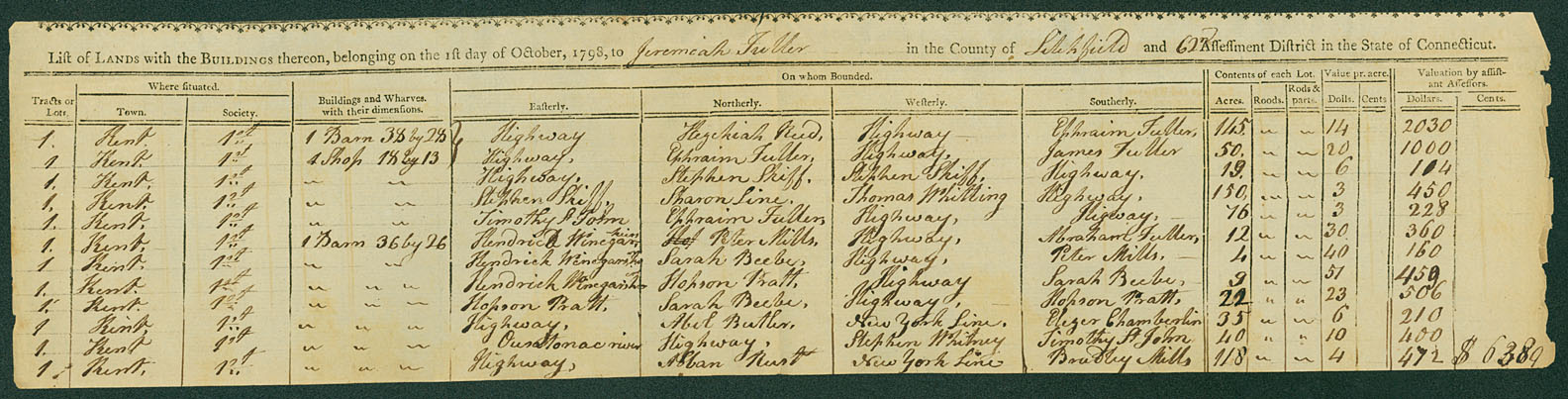

Owners of other real property submitted a second Particular List slip, headed "List of Lands with the Buildings thereon. . . . " These slips also included the name of the owner, and for each separate lot or tract of land, the amount of land, the name of the ecclesiastical society in which it was located, the names of the bounding property owners, and the types and dimensions of all separate buildings for which the sole purpose was "any professional business, or of trade, or mechanic art, or to promote husbandry, and which are calculated & designed to bring revenue to the occupant" unless such a building was inseparable from the dwelling house. These buildings included "stores, shops, offices, manufactories, mills, barns, &c." The assistant assessor valued the property, and posted a value per acre and total valuation for each separate lot or tract of land to the slip.

The owners faithfully recorded instances of part-ownership and, if they claimed an exemption, listed their reason.

The valuations made by the assistant assessors—Timothy St. John and John Payne for Kent and Samuel Carter for Warren—were subjected to public inspection so that everyone in the town would know how their property was valued relative to their neighbors' property. Anyone who disagreed with his or her valuation had the right to appeal it to Principal Assessor John Tallmadge of Warren, who could alter the value assigned by the assistant assessors.

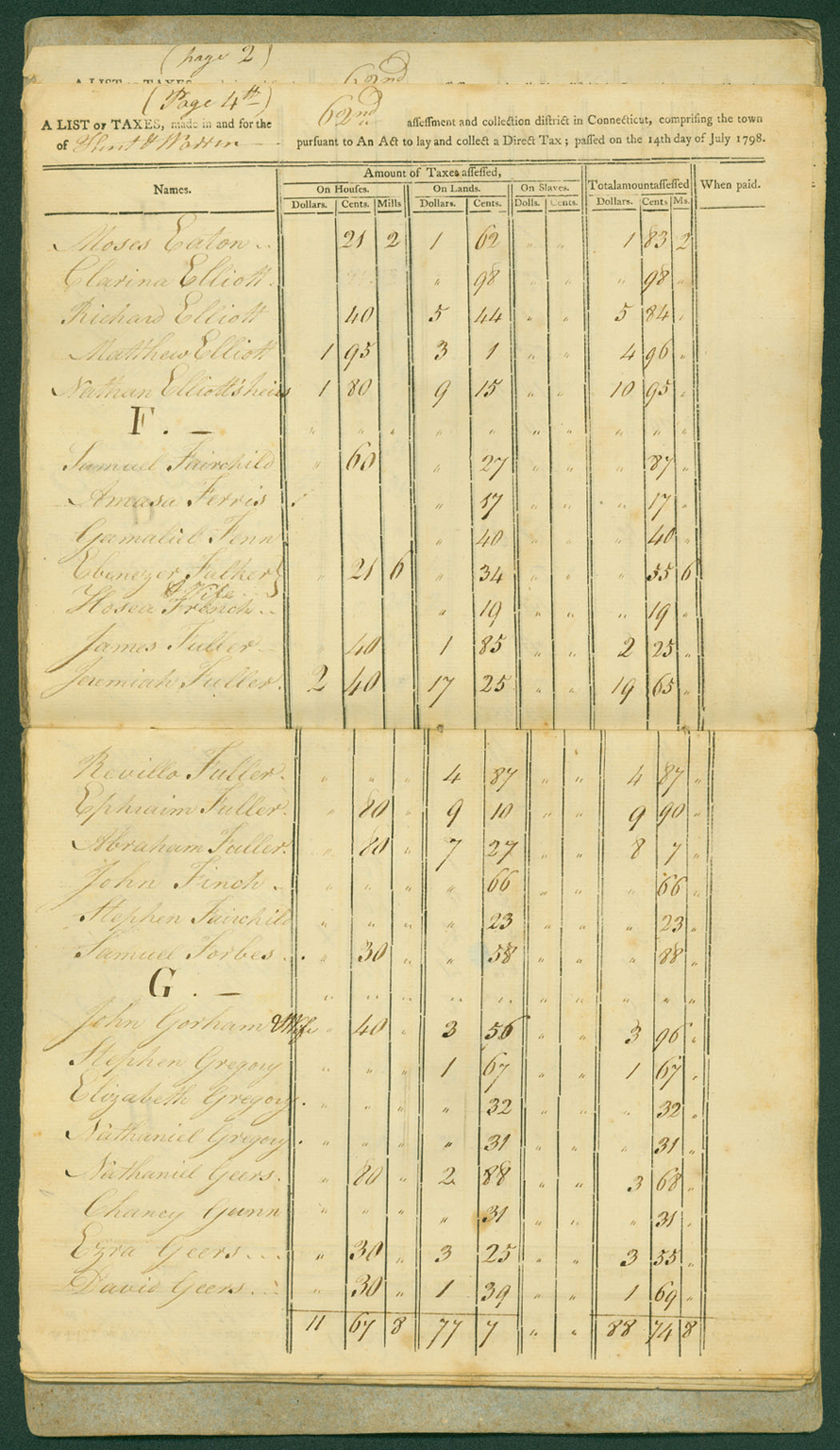

Tallmadge took the information from the Particular Lists and posted the most significant data to the General Lists for the assessment district—one for dwelling houses valued at more than $100 and one for lands.

The valuations made in all of Connecticut's assessment districts were then scrutinized by Connecticut's Board of Commissioners in order to determine if any were inconsistent relative to the other assessment districts. In such cases, the board decided upon percentages that would be used to adjust or "equalize" the valuation of all properties in the affected districts in order to bring all the valuations in line.

The Board of Commissioners sent these equalization percentages back to the principal assessors, who used them to revise the valuations. The principal assessors posted the equalized valuations to the General Lists and forwarded the forms to the surveyors of the revenue. The surveyors calculated the amount of tax for each taxpayer, posted it to the tax collection list ("rate bill"), and forwarded the tax collection lists to the collectors. The collectors were responsible for collecting the tax and for selling property to fulfill delinquent taxes.

How the Kent and Warren Records Were Found

The records found in the regional archives in Waltham were separated into two bundles. Moore found the first bundle of about 900 slips for both Kent and Warren in 2004, along with the tax collection list, and another bundle of Warren slips in late 2005.

The archival staff had been processing customs records for 15 ports that had been stored at the Archives since the 1950s. Before that, the records had been in the possession of the U.S. Customs Service. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) had inventoried the records in the 1930s, wrapped them in brown paper, recorded the identification on the outside of the wrapping paper, and tied the bundles with string. The identification was very general. When the Archives received the records, the staff kept the original WPA descriptions and identification, although in retrospect, as Moore points out, "It's clear that the records had no significance to the person processing them."

Because NARA–Northeast Region (Boston) has placed a high priority on maritime records, five years ago the staff set out to complete the initial, decades-old processing of customs records. This time the archivists looked at the individual documents that were inside each wrapped bundle and verified or corrected how they had been identified. At the time Moore came across the Particular List slips and the tax collection list, he had not previously worked with material from the federal 1798 direct tax, so he had to research exactly what they were and in which record group they belonged. As a result, the staff is in the process of transferring the documents from Record Group (RG) 36, Records of the U.S. Customs Service, to RG 58, Records of the Internal Revenue Service.

Oddly, some of the slips in the second batch of records contain markings that Moore suspects indicate that at some point the records may have been offered for sale—almost certainly while they were still in the possession of the Customs Service. Several dozen of the Warren Particular List slips have a pencil notation in the upper right corner "940/25¢." Because 25 cents bears no relation to the amount of tax, Moore believes that the "940" may be a lot number and the slips so marked were priced to be sold for 25 cents. If this was the case, it is indeed fortunate that there were no takers, but one wonders about other federal records that may have been offered for sale. Therefore it is singularly lucky that these records have survived to the present day, having made the journey from Warren to New Haven to Waltham (and who knows where else in between) over the last 200 years.

Why Were They Found Among Customs Records?

Moore's fortuitous find among customs records was perhaps not unexpected, considering the brief history of the 1798 direct tax and the oddities surrounding the historical custody of the records.

The official, completed copies of the Particular Lists were in the possession of the principal assessor of each assessment district, who was to have turned them over to the surveyor of the revenue of that assessment district once the Board of Commissioners had finalized the equalization process. In the case of Kent and Warren, Tallmadge served both roles. As surveyor, Tallmadge had created the tax collection list—an original that he gave to the collector and a duplicate that he retained so it would be available for public inspection.

After Thomas Jefferson was elected President, Congress reduced the responsibilities of the surveyors of the revenue. An 1801 statute directed the surveyors to send "all the records of the lists, valuations and enumerations" to the top Treasury official in the states—the supervisors of the revenue. It appears that Tallmadge did not comply; if he had, the Particular Lists and tax collection list for Kent and Warren would have been among the official files of Connecticut's supervisor of the revenue, which have not yet been found.

When Congress repealed all internal taxes effective June 30, 1802, the position of supervisor of the revenue in each state was to be abolished once the collection of the taxes owed had been completed. Recognizing that there might be some limited remaining responsibilities, Congress provided that these could be assigned to "any collector of the customs within the state; and where there is no such collector, to the marshal of the district." In Connecticut, when the supervisor of the revenue position was suppressed in October 1802, Commissioner of the Revenue William Miller, Jr., appointed the collector of the customs for Middletown, Alexander Wolcott, to fulfill these responsibilities.

In 1803 Congress authorized the President "to attach the duties of the office of supervisor in any district to any other officer of the government of the United States."

One can only presume that the official files of the supervisors of the revenue were transferred along with the responsibilities.

The Treasury Department never required that the 1798 direct tax records be sent to Washington and centrally preserved, although Miller attempted to initiate such a process in 1803. Had such a directive been issued, the records may not have survived the highly destructive fire at the Treasury building in 1833.

Although there were numerous other federal officials in Connecticut, it seems logical that the Kent and Warren records were turned over to the Customs Service because Customs was then another branch of the Treasury Department.

Why Some Records Survived

The Kent and Warren documents were not the only 1798 direct tax records to be found among customs records. Some time after his employment at the Customs House in Boston commenced in 1844, William H. Montague, a founder of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, came across a janitor putting 1798 direct tax records for Massachusetts (including what later became Maine) into a stove as fuel. Montague stopped the process, and the society acquired the remaining records. And in 1922 the Baltimore Customs House presented the Maryland Historical Society with the 1798 direct tax records for Maryland.

The extant records for Massachusetts, Maryland, and Pennsylvania are almost certainly from the official files of the supervisors of revenue for those three states, having been turned over to federal officials at the suppression of the supervisorships in the early 1800s. While the records for both Massachusetts and Maryland were found at the Customs Houses in their respective states, the Pennsylvania records came from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania to the National Archives.

Although the provenance of Connecticut's General Lists now in the possession of the Connecticut Historical Society Museum is unknown, it is likely that they were once part of the files of Connecticut's supervisor of the revenue. These records, however, are incomplete; about half of the General Lists, the bulk of the Particular Lists, and almost all of the tax collection lists have yet to be found.

Unfortunately, no part of the official files of the supervisors of the revenue in the remaining 12 states has been located. The known, extant records in these states are generally duplicates that were created in response to the statute (for example, the tax collection lists) or the instructions of a particular state's Board of Commissioners (for example, New York required that duplicates be made of Particular Lists). In some cases, the extant records are clearly fragments or working papers for subdivisions of an assessment district, which is the case of the records for Davidson County, Tennessee, and Berkeley Parish in Spotsylvania County, Virginia.

In other cases, duplicates appear to have been kept as personal copies by the men who created the lists, such as the assistant assessors. The summary abstracts for 13 of the 16 states, located at the Connecticut Historical Society Museum, are duplicates made for Oliver Wolcott, Jr.; the location of the official documents sent to Wolcott and his successors (some arrived after Wolcott vacated his office on the last day of 1800) remains a mystery.

Moreover, in cases where lists have been found, they do not always include all the lists that were created for that town or assessment district. In New Jersey, for example, only the dwelling house Particular List survived for Mannington and Pittsgrove, and only the land Particular List survived for Pilesgrove, Salem, and Upper Alloways Creek.

The Missing Official Records

The official files of the supervisors of the revenue that are missing may still exist, but if so are most probably among the records of a non-Treasury branch of the federal government, such as the U.S. Customs, district and circuit courts, the U.S. marshal, the commissioner of loans, the purveyor of goods and services to the United States, the U.S. attorney, the postmaster, or even members of the Congress—all because the 1803 statute allowed the vestigial responsibilities of the supervisors of the revenue to be transferred to "any other officer of the government of the United States."

In five of the states for which the official files have not yet been found—New Hampshire, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia—the responsibility of collecting the 1798 direct tax was transferred to the U.S. marshals. In New York, the responsibility was transferred to the Office of Naval Officer of the Port of New York, a customs official. And in Georgia, the responsibility for collecting the tax was assigned to Commissioner of Loans James Alger in 1806.

According to an archivist at the National Archives, the location of the early records of the U.S. marshals is murky. The marshals were in the unique position of serving two branches of government, executive and judicial. If any 1798 direct tax lists, valuations, and enumerations for New Hampshire, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Vermont, or Virginia are presently located among the federal records of the U.S. Marshals Service, it is unclear in which record group they might be housed. Although RG 21 (District Courts of the United States), RG 59 (General Records of the Department of State), and RG 527 (U.S. Marshals Service) are the most likely locations, it is doubtful that the 1798 direct tax records (if there) would be identified as such. It is far more probable that they would be described simply as "court records" or "marshals records."

A closer examination of the early records in the files of officials to whom 1798 direct tax responsibilities were transferred, as well as the last holders of the office of supervisor of the revenue—both official business records and personal papers—might establish whether any additional records are awaiting discovery.

The Value of the Records

According to architectural historian Robert W. Craig of the New Jersey State Historic Preservation Office, "the records of the 1798 direct tax comprise the best enumeration we will ever have of 18th-century America. They are at once broad and microscopically focused. The particular lists especially allow us a telescopic look at architecture up and down the socio-economic spectrum that we cannot obtain from other sources."

Jack Larkin, chief historian and museum scholar at Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts, indicates that this "comprehensive national census of housing" has enabled historians "to understand that early American houses were substantially smaller than earlier imagined." His use of the Particular Lists for two communities near Sturbridge "inspired the search for evidence about New England's smallest houses"—houses that had previously been overlooked because so few have survived.

Historical geographer Peter O. Wacker indicates that "these lists are marvelous repositories of information on patterns of wealth, house types, and materials of construction, allowing us to make regional comparisons—a natural source for historical geographers and others."

Using the complete set of Particular Lists for a town, one can easily determine the distribution of wealth. In towns with slaves, researchers can use the Particular Lists to distinguish between slaveowners and slaveholders and to determine the economic status of slaveowners versus non-slaveowners. When combined with census population schedules, scholars can determine crowding, that is, the number of people who lived in each house and which individuals were landless. Because the Connecticut forms separately identify instances in which married women owned property in their own right, the information can be used to study women's property ownership.

Of course, the records are valuable because the details offer tremendous insight into living conditions in 1798. As Larkin points out, houses were smaller and a great deal of space was taken by the fireplace and hearth. The families of that period were generally larger, and it was not uncommon to have more than one family living in the same house. The houses were dark and cramped; there was little personal space and less privacy.

Even though over 200 years have elapsed since these records were created, it is possible that additional "lists, valuations and enumerations" for Connecticut and the other states may yet be found. The encouraging discovery of the Kent and Warren 1798 direct tax records indicates that they are still turning up, albeit in unexpected places.

Major 1798 Direct Tax Lists for Connecticut

Known, Extant 1798 Direct Tax Lists

Judith Green Watson is researching the nationwide implementation of the 1798 direct tax. Her article about the implementation of the tax in Connecticut appeared in the Fall 2006 issue of Connecticut History.

Notes on Sources

The Particular List slips for Kent and Warren, as well as the tax collection list, are among the papers of William Munson, Surveyor for the District of New Haven and Inspector of the Revenue, in Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group (RG) 36, at NARA–Northeast Region (Boston). There are plans to microfilm these records. Until then, they are available to researchers for inspection in Waltham. Munson's appointments to the New Haven Customs positions are contained in the Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate (Washington, DC: Duff Green, 1828).

The Pennsylvania 1798 direct tax records are in Records of the Internal Revenue Service, RG 58, National Archives at College Park, MD. The valuation and enumeration lists are in Series 9, "Assessment Lists for the Pennsylvania Direct Tax, 1798–1800." The lists have been microfilmed as United States Direct Tax of 1798: Tax Lists for the State of Pennsylvania (National Archives Microfilm Publication M372). The accompanying descriptive pamphlet identifies lists for all 38 assessment districts by town and county, but does not indicate whether the surviving records are Particular Lists or General Lists. Other Pennsylvania records, primarily correspondence and reports, are located in RG 58, Series 8, "Letters Sent by the Supervisor of the Pennsylvania Direct Tax, 1802–1803," and Series 12, "Weekly Returns of Henry Miller, Supervisor of the Pennsylvania Direct Tax, 1795–1802," at NARA–College Park; these are described in Forrest R. Holdcamper, Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Internal Revenue Service (Record Group 58), NC-151, (Washington, DC: General Services Administration, 1967).

Other NARA records that contain material pertaining to the 1798 direct tax include Circular Letters of the Secretary of the Treasury ("T" Series), 1789–1878 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M735), General Records of the Department of the Treasury, RG 56; Letters Sent by the Commissioner of the Revenue and the Revenue Office, 1792–1807 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M414), RG 58; Miscellaneous Treasury Accounts of the First Auditor (Formerly The Auditor) of the Treasury Department, September 6, 1790–1840 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M235, roll 46), Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury, RG 217; and "A Record of the Reports of the Secretary of the Treasury, 12th Congress, 1st Session–13th Congress, 3rd Session, 1811–1815, Volumes XI–XII," in Transcribed Reports and Communications Transmitted by the Executive Branch to the U.S. House of Representatives, 1789–1819 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1268, roll 8), Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, RG 233. Microfilm Publication M414, roll 3, is particularly important because it documents to whom the responsibilities of most of the supervisors of the revenue were transferred, as well as Miller's recommendation to Gallatin—never acted upon—that the "Tax Lists, Valuations & Enumerations" be centralized at the Treasury Department in Washington.

The Connecticut "Board of Commissioners Record Book, 1798," in the library of the Connecticut Historical Society Museum in Hartford, contains the definition of the types of buildings included on Connecticut's Particular List of Lands (pp. 18–21) as well as the names of the Kent and Warren assessors (p. 16).

The description of the discovery of the Massachusetts 1798 direct tax records is contained in "Returns of the United States Direct Tax of 1798," The New England Historical and Genealogical Register 45 (January 1891): 82–83. A list of the donated Maryland 1798 direct tax records can be found at the Maryland Historical Society web site .

Jack Larkin's article "Big House, Middling House, Small House: Housing in New England at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century" is found in Old Sturbridge Visitor 44 (Fall–Winter 2004–5): 4–6.

In addition to the major 1798 direct tax records described in the sidebar, there were two other important records created. The first was a book or form used by the surveyors of the revenue to record all transfers of land, changes in ownership, and alterations in value; this may have been accompanied by detailed maps. The second was a book or form used by the collectors to record all sales of real property for nonpayment of taxes.

This Kent house in the historic Flanders District dates from the 1798 direct tax era and typifies small, one-story homes of early Kent and Warren. (Kent Historical Society, CT)

This Kent house in the historic Flanders District dates from the 1798 direct tax era and typifies small, one-story homes of early Kent and Warren. (Kent Historical Society, CT)

The Matthew Alger home (pictured in the early 1900s) appears on the 1798 Particular List for Warren, Connecticut. It measured 36 x 24 feet, had seven small windows, and was valued at $50 and taxed at 14 cents. (Warren Historical Collection, CT)

The Matthew Alger home (pictured in the early 1900s) appears on the 1798 Particular List for Warren, Connecticut. It measured 36 x 24 feet, had seven small windows, and was valued at $50 and taxed at 14 cents. (Warren Historical Collection, CT)