Mission to Štĕchovice

How Americans Took Nazi Documents From Czechoslovakia—and Created a Diplomatic Crisis

Winter 2007, Vol. 39, No. 4

By T. Dennis Reece

© 2007 by T. Dennis Reece

On May 22, 1946, Karl Hermann Frank was hanged in Prague, Czechoslovakia, for war crimes. During World War II he was the de facto leader in the Nazi occupation of the provinces of Bohemia and Moravia. His crimes included partial responsibility for the infamous massacre in the village of Lidice in 1942. In reprisal for the assassination in Prague of SS Lt. Gen. Reinhard Heydrich, the village was destroyed after all the male inhabitants were shot, and the women and most of the children sent to concentration camps.

Although the American press reported on Frank's trial and execution, it did not reveal that key evidence used to convict him came from a top-secret military intelligence mission to Czechoslovakia, code-named Operation "Hidden Documents," organized by U.S. authorities in occupied Germany. Ironically, Lionel S.B. Shapiro, a Canadian journalist, was a member of the mission. His eyewitness account was published in numerous newspapers shortly afterward. The American press also reported the U.S. government apology in response to Czechoslovakia's official protest that Operation "Hidden Documents" had violated its sovereignty.

After a British magazine in May 1946 published six pictures of the mission, Operation "Hidden Documents" quickly faded from public view, and ever since has been neglected by both intelligence and diplomatic historians. The story of the mission, however, especially its genesis and consequences, can be told through declassified material from several military entities and the State Department now in the National Archives.

The seizure of Nazi documents by Allied forces began while Europe was being liberated. Combat units sometimes discovered document collections by accident; special document units attached to field armies or army groups located other collections. Some documents, including Adolf Hitler's marriage certificate to Eva Braun, were found through investigations by Counter Intelligence Corps members and related specialists. During the war, except for material on Japanese or German secret weapons, most document collections were not moved. After V-E Day, document searches continued vigorously. By the end of 1945, American authorities had thousands of tons of Nazi documents spread throughout their German zone of occupation. Moreover, other occupying powers had valuable documents in their zones in Germany, and many countries, whether occupying powers or not, were interested in recovering documents the Nazis had taken from them during the war and relocated to Germany.

The U.S. government's top authority on captured German documents at this time was the Document Control Section in the Operations Branch of the G-2 (intelligence) staff at U.S. Forces European Theater (USFET) headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany. In July 1945, USFET had assumed command of all American military forces in northwest Europe. Working closely with representatives of other U.S. government agencies, foreign governments, and key document centers, the Document Control Section formulated policies for acquiring, processing, and sending to appropriate recipients captured documents. It also supervised operations at document centers in the American zones of occupation in Germany and Austria. Among other purposes, captured documents were used as evidence in the famous 1946 Nuremburg trials and other war crimes prosecutions, in denazification programs in Germany and Austria, for evaluation by American and British intelligence analysts, and for family reunification of refugees through the U.N.

The search for documents was not limited to Germany and Austria. Based on reporting from the American embassy in Prague, the Department of State believed that during the war Germany had sent documents to Czechoslovakia for safekeeping at up to 50 locations. In late 1945 the Czechoslovak government agreed to work with the United States on the subject and hosted a visit in January 1946 of two State Department document experts. Ministry of Foreign Affairs representatives told them that there were 20 identified document sites, but only two of them, both castles, probably had anything more than library books. The experts, accompanied by a ministry archivist, visited one site, which revealed nothing promising. They proposed to return in three months, which would give Czechoslovak authorities time to sort and catalog their holdings.

A Secret Cache Is Reported

Unbeknownst to both sides, developments were under way that would soon make another document collection command the attention of high-level officials in both Czechoslovakia and the United States. The process started in November 1945 when SS Sgt. Gunter Achenbach, a POW, told his French captors that he had been an instructor at an SS engineering school near Štĕchovice, a town on the Moldau (Vltava) River about 25 miles by air south of Prague. In April 1945 he helped dig a cave in the side of a ravine in the woods several miles outside Štĕchovice. The cave was about 30 feet deep, 6 feet high, and 5½ feet wide. It was lined with wooden boards and had been extensively booby trapped with explosives. He was not there when the cave was filled, but another SS noncommissioned officer told him that two trucks had taken documents there. Achenbach said he helped camouflage the cave with dirt and vegetation after it was closed so that no one could tell there had ever been any digging there. He offered to go back to point out the site.

The French relayed Achenbach's story to the Americans, who thought it sounded promising. Fearing that a leak would compromise any operation, USFET G-2 moved with great secrecy. Some U.S. government offices that normally would have been in the information loop were kept completely in the dark, while others were only partially informed. In December 1945 USFET, without fully revealing why, requested that the air attaché at the American embassy in Prague get aerial photographs of the area around the cave. Later Achenbach was taken to Germany for detailed interrogation, after which his story was judged to be credible. Without providing further details, USFET next requested that the office of the military attaché in Prague arrange for a group of 14 American military personnel to enter the country in connection with the December photographic mission.

USFET informed Robert Murphy, a career diplomat, about the project. With the rank of ambassador, he was the highest civilian official in the American occupation government and political adviser to its chief in Berlin, Lt. Gen. Lucius Clay. For months Murphy's job partly involved civilian and military efforts to recover German documents, including the January 1946 visit by State Department experts to Czechoslovakia. He did not, however, inform the State Department about this latest project of USFET G-2. Nor did USFET advise the War Department about Achenbach's story and what actions it was taking.

The man in charge of Operation "Hidden Documents" was Lt. Col. M. M. Spiegel, chief of the USFET G-2 Document Control Section. He assembled a team of 13 men with a variety of specialties from four countries. Co-commander during the mission would be 1st Lt. William J. Owen, an intelligence officer in the Document Control Section. First Lt. Leo A. Silberbauer was the French liaison officer to the Document Control Section, where he had established an effective working relationship with Owen. Sergeant Achenbach had to go to locate the cave and would have a French guard, Sgt. Antoine Vital. First Lt. William J. "Wayne" Leeman, in charge of still photographic assignments for the Signal Corps in the theater, was asked to find a photographer. Normally an enlisted man would have been chosen. But Leeman, who had been a St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter before the war, knew a good story when he heard one and assigned himself. Lionel Shapiro apparently heard about the mission from French sources and was allowed to participate on the condition that he embargo his story until military authorities released it. Several drivers, including Privates Carmine Catusco and John Ecker, both from the 3578th Quartermaster Truck Company, were also assigned.

The success of the mission, and even the lives of many of its members, would depend on the men who would try to neutralize the explosives Achenbach believed were in the cave. Capt. Stephen M. Richards, who had commanded the 123rd Bomb Disposal Squad in Patton's Third Army drive from France through Luxembourg, Belgium, and Germany to Czechoslovakia, was the lead explosives expert and co-commander. Staff Sgt. Taylor R. Fulton and Sgt. Philip J. Urquhart, both veterans from the 1264th Combat Engineer Battalion, were to assist Richards.

The Documents Are Extracted

During the afternoon of February 10, the "Hidden Documents" team went through the border checkpoint just east of Waidhaus, Germany. They used passes from the Czechoslovak liaison office in Regensburg, Germany, that the American military attaché in Prague had helped obtain without revealing the true purpose of the expedition. The group traveled in five vehicles: a command and reconnaissance car, two 2½-ton cargo trucks, a weapons carrier, and an air compressor truck used by combat engineers.

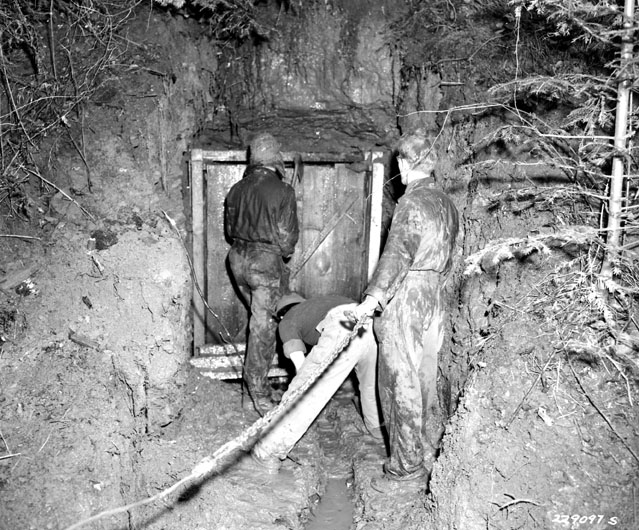

The next morning Achenbach guided the team to the woods outside Štĕchovice. Without too much difficulty he found the cave's camouflaged location as Fulton and Urquhart probed for mines. The rest of the morning was spent digging. After the top of the cave was exposed, the explosives experts had to work slowly, removing dirt while probing for booby traps until the entrance wall, made of several wooden boards, was uncovered.

Achenbach did not have a wiring diagram. With a combination of experience, ingenuity, and luck, however, Richards neutralized the first, and most dangerous, obstacle. First he fortuitously ordered removed the only board of the entrance wall that was not attached to detonators wired to explosives inside. Then he reached inside the cave and cut all the connecting wires he could see. Just before darkness fell, the front door was pulled off without incident.

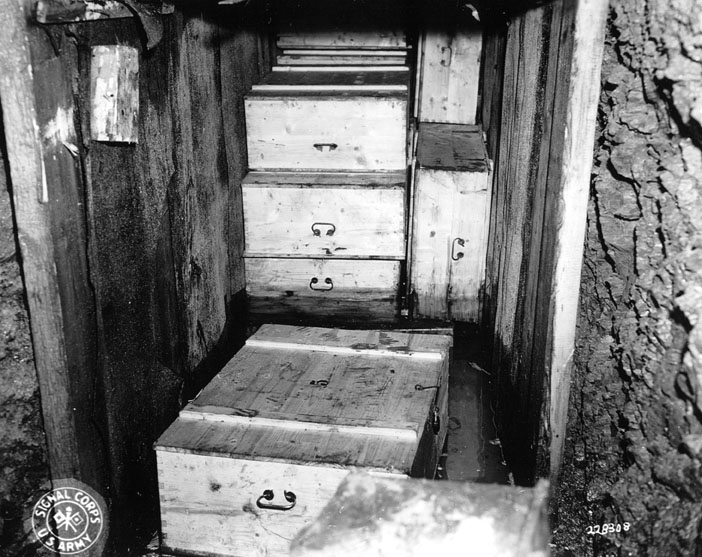

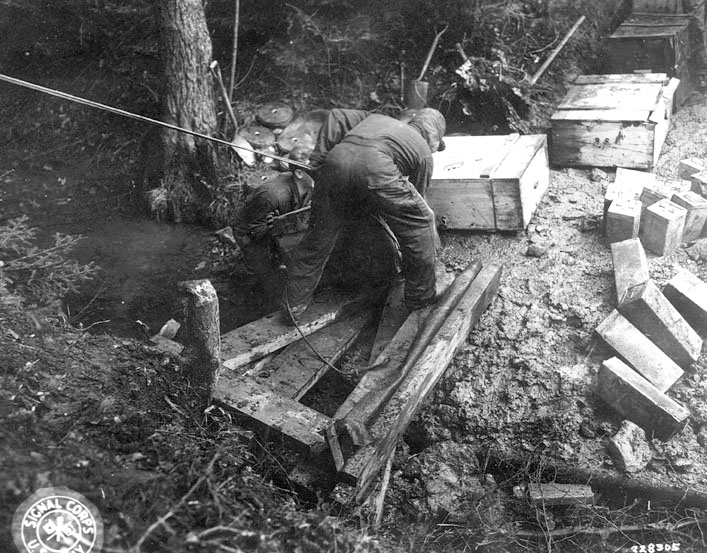

The next day, February 12, it was revealed that 32 wooden crates were inside the cave. As each was taken out, Richards, Fulton, and Urquhart checked for booby traps around the remaining crates. About one ton of explosives and associated material was removed. The SS intended that anyone breaking in by removing the entrance wall would set off Teller mines, which in turn would explode containers of dynamite and ignite cans of flammable oil. In the process the intruder would be instantly killed, and a fire would start, burning the cave's contents.

Moving the crates up the long, steep, slope from the ravine to the cargo trucks was arduous. Each one was about four feet long, three feet wide, two feet high, and weighed 400 pounds. Mud made the footing slippery. All mission members assisted, using a winch on one of the trucks and some unexpected help. Three Czech civilians appeared who were curious about all the activity. The language problem hampered communication, but after seeing what the Americans were doing, they pitched in, lifting crates into the trucks and helping with the rest of the operation. They were rewarded with cans of corn, boxes of cereal, and packs of cigarettes.

Earlier on two occasions, Czechoslovak soldiers had approached the area, apparently alerted by a local woodcutter. Captain Richards went out to give them cigarettes and said they were digging for the graves of American soldiers. On neither occasion did the soldiers ask to inspect the area of the cave. Their curiosity seemed satisfied, but the Americans did not know whether either meeting had been reported to superior officials, who could have ordered special controls placed on the roads and at border crossing points.

By 8:30 p.m. the trucks were loaded, and the disarmed explosives and flammable oil put back in the cave. To decrease the chance of being stopped by local authorities, the trucks with documents had to leave for Germany immediately. The explosives team, however, would stay in Prague with the weapons carrier for two or three days to recover from their mental and physical ordeal. They would also act as decoys. As far as Owen knew, Czechoslovak authorities had not discovered what the group was doing, or at least was not interested in stopping them. If he was wrong, the presence of the trio in Prague might make the authorities think the rest of the party was somewhere in the country rather than on the road to Germany.

A Diplomatic Crisis

The main party crossed into Germany early in the morning of February 13. That evening, the three explosives experts were picked up at their Prague hotel and taken to Czechoslovak General Staff headquarters for interrogation. It was not clear how the authorities learned about the mission, but it was plain they were not happy. On February 15 a General Staff liaison officer told Captain Johnson, an assistant military attaché at the American embassy, that the trio had been arrested for its part in the Štĕchovice incident and that they would not be released until the crates were returned and an explanation given. Johnson's request to see the three was refused.

Within several days, working-level officials in the War and State Departments met in Washington to discuss the problem. The State Department thought the United States could keep the documents, have the arrestees released, and avoid publicity if American Ambassador to Czechoslovakia Laurence A. Steinhardt apologized and a member of the Czechoslovak intelligence service was invited to examine the seized material.

After being briefed on the Washington discussions, USFET Commander in Chief Gen. Joseph T. McNarney and Ambassador Murphy conferred on February 20. McNarney approved Murphy's proposal that the U.S. government contact Lt. General Palaček, who was head of the Czechoslovak Military Mission in Berlin and a representative of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with the rank of ambassador. Palaček could be told that first, the Czechoslovak government was not informed of the mission ahead of time simply for reasons of operational security, and second, the United States had always intended to share with Czechoslovak authorities whatever information was obtained from the crates, of whose contents the United States only had a vague idea in advance. McNarney and Murphy also agreed that if the United States could reach agreement with the Czechoslovaks on sharing the information or returning the documents, it would not be necessary to either make an apology or issue a press release.

While all the discussions had been going on, experts under Lt. Colonel Spiegel's supervision had been examining and cataloging the seized material at a military intelligence document depository near Frankfurt. A preliminary analysis determined that the crates included archives of the German occupation office for Bohemia and Moravia from 1940 to March 1945, Gestapo and SS security service files on the provinces, pre-war official and personal files of President Eduard Beneš, and inventories of treasures in Bohemian castles.

A February 18 diplomatic note from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the American embassy in Prague soon dashed hopes in Germany and Washington that the United States would be able to blithely talk its way out of the situation. The note objected to the "patent infringement upon the sovereignty" of Czechoslovakia, requested an explanation "within the shortest possible time," and expressed the expectation that the removed material would be returned.

The embassy's telegram about the note was received at the State Department on February 21. That evening Secretary of State James F. Byrnes talked with Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson. They agreed that Ambassador Steinhardt should apologize to the Czechoslovak government and inform it of the contents of the crates. Furthermore, he was also to say that the documents would be returned, and details of the operation would be given to the Czechoslovak government by American military authorities. The State Department's telegram to Ambassador Steinhardt on the meeting instructed him to explain that the operation was undertaken by American military authorities in Germany "without the knowledge or approval of the US GOVT," and that details would be furnished to Lt. General Palaček. Steinhardt was also authorized to explain that the operation was designed to obtain secret documents buried by the Nazis, the contents of which had only become known afterward.

On Saturday, February 23, Steinhardt called on Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk, as President Beneš was not in Prague. Masaryk readily accepted the apology and the explanation that the U.S. government had not approved or known about the operation. He said the incident would be closed when the documents were returned. On the same day, in response to press inquiries, the State Department issued a press release on the incident, and USFET moved to lift its embargo on Shapiro's story. It ran in the New York Times and other American newspapers on February 25.

In a subsequent meeting with the ambassador, President Beneš also graciously accepted Steinhardt's apology and requested that the documents be taken directly to his palace office. After microfilming items of interest, USFET G-2 personnel loaded, sealed, and dispatched the crates as Czechoslovak officials watched. The material arrived at the presidential palace on March 2. That evening, Czechoslovak authorities took Richards, Fulton, and Urquhart there to view the documents, then returned them to General Staff headquarters for a dinner with wine. The trio was released the next morning.

Hooray for the Cowboys

Although good U.S.-Czechoslovak official relations had been restored, and the explosives experts were soon back in Germany, a public relations disaster had been ignited that threatened to seriously damage U.S. interests. Communist Party members or sympathizers held 9 out of 22 senior-level positions in the Czechoslovak government, including prime minister, both deputy prime ministers, and ministers of defense, interior, information, and education. The party thus acquired a higher level of influence in the government than it had in the country as a whole, exercising control over many key sectors, including all of the security services and much of the media.

Elections for two national assemblies, one for Bohemia and Moravia and the other for Slovakia, were scheduled for May 26, 1946. The new bodies would replace the country-wide Provisional National Assembly, which had not been constituted through a general popular vote.

Not surprisingly, the Štĕchovice incident initially was roundly criticized by all Czechoslovak political parties. The first public report describing it, issued by the official news agency, was very negative toward the United States. Carried in local newspapers on the morning of February 23, it characterized the Štĕchovice mission as "an infringement of Czechoslovak sovereignty." Mladá Fronta, the newspaper of the pro-Communist youth association, headlined the operation a "hostile act."

Naturally, the Communists were delighted with the propaganda possibilities. Thousands of Soviet and American troops had been stationed in Czechoslovakia until they simultaneously withdrew in December 1945. Although some complaints had been made about the behavior of American troops, Soviet forces had caused wider resentment with their more egregious conduct. Štĕchovice handed the Communists a tool to make the Czechoslovaks forget about the misbehavior of their eastern liberators.

Steinhardt perceived that he had to limit the damage done to moderate, pro-Western political forces in Czechoslovakia, especially in the period before the upcoming elections. Like Beneš, Foreign Minister Masaryk was one of the major moderating forces in the government. During their meeting on February 23, he had, at Steinhardt's suggestion, drafted a Ministry of Foreign Affairs press release to help counteract the unfavorable publicity the American government was receiving. The statement, carried in all Prague newspapers the next day, was helpful in widely publicizing the American apology and promise to return the boxes. Mladá Fronta headlined its coverage "Stolen Cases Will Be Immediately Returned." The statement also described in general terms the contents of the cases, which helped end the public rumors that had spread in the absence of reliable information.

The statement, however, could not erase the fact that, regardless of what level of the American government had approved the operation, the crates had been removed without any Czechoslovak authorization. During the next week, editorials in Prague newspapers across the ideological spectrum condemned the United States for its violation of Czechoslovak sovereignty. Criticism by moderate elements subsequently abated, but hoping to gain an advantage for the upcoming elections, the leftists kept attacking, both in the press and in the Provisional National Assembly.

After the crates from Štĕchovice were returned to Beneš' office, they were opened in the presence of representatives of all political parties and the Ministry of Interior. Also present was Jaroslav Drábek, chief prosecutor for war crime trials in Czechoslovakia, who combed through the contents, looking for useful material.

In late March 1946 the trial of Karl Hermann Frank began. A number of witnesses to Frank's crimes over the years were available to testify, but as the trials of the major war criminals at Nuremberg showed, fixing responsibility for that kind of crime was much easier if documentary evidence could be introduced to corroborate eyewitness testimony.

Numerous documents unearthed from the cave outside Štĕchovice were introduced during Frank's trial as evidence against him. An April 3, 1946, article in Svobodné Slovo, the official newspaper of the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party, asserted that without those documents the prosecution would have had a very difficult time proving its case against Frank. The newspaper, which had previously condemned the U.S. for its violation of Czechoslovak sovereignty, completely changed its point of view. It editorialized "So, we must actually say 'Thank God' for the cowboy-like action of the Americans."

In the National Assembly elections for Bohemia and Moravia, which the American embassy in Prague judged to be free and fair, the Communist Party did not attain its goal of winning a majority of legislative seats. It did, however, garner a 40-percent plurality. Beneš and Masaryk continued as president and foreign minister, respectively, when the new cabinet was formed in July 1946, and the Communist Party kept control of its key governmental positions.

Like many historical events, Operation "Hidden Documents" is open to different interpretations. From one viewpoint it can be seen as one of the most daring military missions of the 1940s, highlighting the skill, courage, and ingenuity of the citizen officer and soldier. (Richards, Fulton, and Urquhart were awarded the Soldier's Medal, the United States' highest award for bravery not in action against the enemy). From another viewpoint the mission can be seen as an example of American arrogance and disrespect for other countries' sovereignty, notwithstanding good intentions.

The operation may well not have succeeded unless USFET G-2 had run it with extraordinary secrecy. If the excavation had been done under other auspices, it is questionable whether any recovered material would have been made available for nonpartisan use, given Communist control of many key security and political positions at the time. In this light, the legacy of Operation "Hidden Documents" is that it produced strong evidence of the horrors of Czechoslovakia's first totalitarian regime before the country succumbed to its second.

T. Dennis Reece is a retired U.S. State Department Foreign Service officer and author of the book Captains of Bomb Disposal, 1942–1946, from which this article was adapted.

Note on Sources

Primary documentation for this article came mainly from four record groups in the National Archives at College Park, MD. Useful material is in the Records of the European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army/U.S. Forces, European Theater (Record Group 498), which include: Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, records of the Operations Branch and subordinate sections and Miscellaneous Records, 1944–1946, of the Administration Branch; and USFET G-2 records of the Military Intelligence Service Center. Most helpful in the Records of the Army Chief of Staff (Record Group 319) were the Plans and Operations Division's 1946–1948 Decimal File, and two collections from the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2: Incoming and Outgoing Messages, 1946, Czechoslovakia; and State Department Files, Czechoslovakia, Reports and Messages, 1918–1951. The 1945–1949 Decimal File in the General Records of the Department of State (Record Group 59) had many relevant items. Annotated photographs of Operation "Hidden Documents" were in the Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer (Record Group 111).

The following volumes in the State Department's Foreign Relations of the United States series were used: 1944, volume IV; 1945, volume IV; 1946, volume VI; and 1947, volumes III and IV.

The author benefited from his interviews of Stephen M. Richards and Wayne Leeman, and from his access to their personal papers on the mission.

The primary secondary works utilized were Lucius D. Clay, Decision in Germany (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1950); Eugene Davidson, The Trial of the Germans (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1997); Josef Korbel, The Communist Subversion of Czechoslovakia, 1938–1948: The Failure of Coexistence (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1959); Vojtech Mastny, The Czechs Under Nazi Rule: The Failure of National Resistance, 1939–1942 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1971); Robert Murphy, Diplomat Among Warriors (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964); Ian Sayer and Douglas Botting, America's Secret Army: The Untold Story of the Counter Intelligence Corps (New York: Franklin Watts, 1989); Hugh Seton-Watson, The East European Revolution (New York: Praeger, 1971); Mikulas Teich, ed., Bohemia in History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Adam B. Ulam, Expansion and Coexistence: The History of Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917–67 (New York: Praeger, 1971); Walter Ullman, The United States in Prague, 1945–1948 (New York: Eastern European Quarterly, 1978); and Earl Ziemke, The United States Army in the Occupation of Germany 1944–1946 (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1975).

Also consulted were the New York Times, February–October 1946, and the Illustrated London News of May 11, 1946.

Updated Aug. 26, 2008