LBJ: Still Casting a Long Shadow

Summer 2008, Vol. 40, No. 2

By Harry Middleton

© 2008 by Harry Middleton

Lyndon B. Johnson counted on history to make the final assessment. "I hope it may be said, 100 years from now," he told the Congress as he departed Washington in 1969, "that we helped to make this country more just. That's what I hope. But I believe that at least it will be said that we tried."

The century he set for evaluation is still a long way off. But this year affords another opportunity. It is the centennial of LBJ's birth, an appropriate occasion to reflect on the life of the man who once loomed so large on the national stage—to reflect particularly on the five years of his presidency.

"History should make no mistake," Joseph Califano, one of his chief lieutenants of those days says of him. "Lyndon Johnson was a revolutionary and what he let loose in this country was a true revolution." Johnson was "the man who fundamentally reshaped the role of government in the United States," says historian David Bennett of Syracuse University. Barbara Jordan, in the last year of her life, gave her assessment of what that reshaping amounted to: "He stripped the government of its neutrality, and made it an agent on behalf of the people."

His legacy—his revolution, if indeed that is what it should be called—was an avalanche of legislation.

When Johnson was majority leader in the Senate, reporters started calling him powerful. His reaction was that the only power he had was the power to persuade—which prompted another senator to observe, "Good God Almighty, that's like saying the only wind we have is a hurricane." It was legendary, but it was real, and it was a power Johnson carried with him into the White House. John F. Kennedy had had an ambitious agenda, but he had faced a Congress that was often hostile and almost always reluctant to move. So many of the Kennedy initiatives were still stalled in committees.

In virtually no time, Johnson—catapulted into the presidency after Kennedy's assassination—changed that condition. Along with his ability to bring reluctant senators to his side of a proposition, he skillfully exploited the trauma the nation experienced in the wake of Kennedy's murder—a sense that the country wanted to feel that something important and worthwhile was being accomplished in the midst of tragedy. The result was the outpouring of legislation that would continue—although encountering significant speed bumps caused by the war in Vietnam—right on to the end of his administration five years later.

The list of those legislative achievements was staggering, because his vision was large, and his reach was wide.

There were programs designed to reduce the conditions of poverty in which too many Americans were trapped. He stunned many of his old constituents by declaring war on poverty in the early days of his presidency. Although he had begun his career in Congress as a staunch supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt, in the Senate, representing an entire conservative state, he had tacked to the right. And now he was committing his power to the cause of the poor. "Before I am through," he said, "no community in America will be able ever again to ignore the poverty in its midst."

There were several programs to provide new educational opportunities for America's youth. Education was the real road out of poverty, Johnson believed, and he wanted to be the Education President. To dramatize his commitment to the cause, he went to the one-room schoolhouse where he had attended first grade and signed the breakthrough law that committed federal funds to shoring up the deteriorating educational system for grade- and high-school students. He brought his first-grade teacher out of retirement to sit beside him. Then a year later he went to the campus of his alma mater in nearby San Marcos to sign the law opening the doors of college to millions of new students with student loans and scholarships and other programs.

There was medical insurance for the elderly. President Harry S. Truman had tried in his time to get some form of medical insurance for older citizens, but he had been beaten down by the medical lobby. Johnson took the legislation creating Medicare to Independence, Missouri, to sign it in Truman's presence.

There was liberalized immigration, which he signed in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty. There were laws to protect the environment—small steps, but the first. "We trotted the subject out on the stage," Lady Bird said. She herself was the inspiration and guiding force behind the effort to remove or screen ugly junkyards bordering American highways, and remove the billboards that were destroying the traveler's view of his homeland.

There were laws to protect the consumer in the market place, and for the first time, a commitment by the federal government to bring art and music and theater to all parts of the country and to promote the study of the humanities.

Of all his accomplishments, those with the most immediate—and at the same time, the most far-reaching—effect were the civil rights acts of the 1960s.

Kennedy had proposed a law that would have outlawed discrimination in public accommodations, but it never got to the floor of either the House or Senate. Johnson urged Congress to pass it as a memorial to the fallen leader, and he put the full muscle of his administration behind his plea.

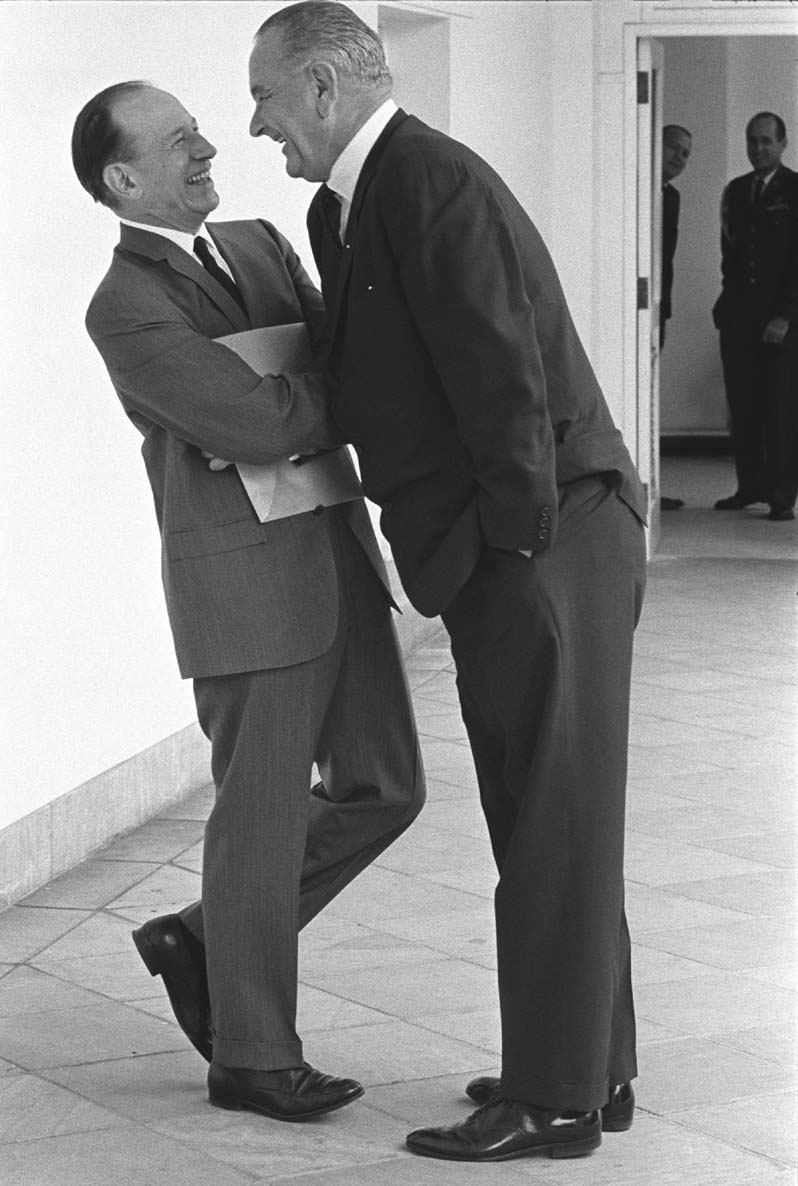

"We have talked long enough in this country about civil rights," he told Congress in his first speech as President. "We have talked for one hundred years or more. It is now time to write the next chapter and write it in the books of law." Eventually, the key to passing the measure was Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican leader from Illinois. Only Dirksen had the clout to persuade his fellow Republicans to vote to break a filibuster being staged by opposition Southerners. Dirksen was not known for any particular interest in civil rights—but he was known to be highly susceptible to flattery. So Johnson—at his persuasive best, or his shameless worst, depending on how you look at it—went to work. And the Texas President assured the Illinois senator that if he would take the leadership in getting the bill passed, Illinois school children would hereafter know only two names to honor—Abraham Lincoln and Everett Dirksen. Finally, Dirksen announced his recognition of an idea whose time had come. The bill passed. That was in 1964.

In 1965, the issue was voting rights. Many southern states had routinely been denying blacks, through a series of subterfuges, their constitutional rights. And now black determination and white southern resistance were at a flash point.

Johnson went before Congress to ask for legislation that would put the force of law behind those constitutional rights, appropriating the words of the civil rights movement itself, "We Shall Overcome" the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. It was the most impassioned speech of his career. When the measure passed, Johnson was asked by reporters how he squared his new concern for civil rights with the fact that he had voted against civil rights proposals when he was in the Congress.

"I did not have the responsibility then that I have now," he answered, "and I did not feel its importance as I now do. But I am going to do everything I can to right the wrongs of the past, no matter how many mistakes I may once have made."

At the end of his administration, his cabinet gave him a desk blotter on which were inscribed the titles of 300 major laws passed under his leadership. And those were just the tip of the iceberg. In all, there were a thousand laws of the Great Society.

But when he left office, his thoughts were on work still to be done. He spoke of it often in the last years of his life. He expressed his conviction that every boy and girl in this country had the right to as much education as he or she could take. He believed that good medical care was a constitutional right "from the cradle to the grave."

In concluding remarks at a conference on civil rights the month before he died, he warned: "Let no one deceive himself that the work is finished." He thought government had done all in its power, but now it was the responsibility and challenge of the universities, the churches, and the business community to assure, at long last, that black and white citizens stand on equal ground.

He had in many ways equaled—and in others surpassed—Roosevelt's record. He accepted that distinction with pride. But, although his agenda had clearly been a liberal agenda, he did not care for the designation of liberal himself. Liberals had given him a hard time throughout his Senate years, and even in the White House, despite what he was achieving, they distrusted him. He returned the favor. "The difference between Liberals and cannibals," he said, "is that cannibals eat only their enemies."

Many of the laws of Johnson's Great Society are still on the books, having been kept alive through succeeding administrations, Republicans and Democrats alike. And a generation later it can fairly be said that his revolution has changed the way we live in America.

Johnson's domestic achievements were only part of his legacy, of course. There is also the elephant in the room named Vietnam.

The overwhelming preponderance of scholarly work on Vietnam today—an estimated 90 percent—holds that the American involvement in that war was a mistake. Historians in the future may redress that balance, but in this centennial year we are faced with history as it is written and revealed now.

Johnson inherited the war in Vietnam, and the commitments of the two Presidents who preceded him to assist South Vietnam defend itself against the efforts of the Communist North to take it over. He was as much a Cold Warrior as Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy—and indeed the nation at large—were. He believed as fervently as most of his countrymen did in the danger of falling dominoes. But Johnson also—we know this because of his once-secret telephone conversations—revealed early in his presidency his fears of getting trapped in a war that couldn't be won.

Yet it was Johnson who changed the course of the war—Americanized it, in effect—by sending in U.S. forces to fight and not just advise the South Vietnamese, which had been the American mission. From this there was no turning back. Tensions grew. Protests rocked and then divided the country.

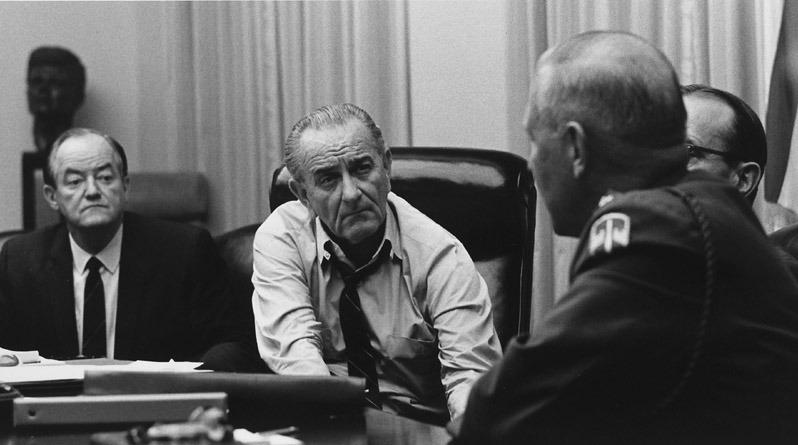

That critical decision was made by Johnson in the spring of 1965, when the war was steadily being lost. The only hope of "turning the tide," said his secretary of defense, secretary of state, national security adviser, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was to commit combat troops.

"A President's hardest job," Johnson said many times, in office and out, "is not doing what's right, but knowing what's right." He added that sometimes the only way to know is to "listen to the best advice you can get and to your own gut."

He heard voices of caution. "I don't believe we can win under these conditions," Undersecretary of State George Ball said. Clark Clifford, an old and trusted friend who would eventually become secretary of defense, warned, "I can't see anything but catastrophe." Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield predicted, "We are going deeper into [a] war [that] we cannot expect our people to support."

This advice weighed heavily, but it was trumped by the voices urging action. And the strongest and most sobering of those was Dean Rusk's: "The integrity of the U.S. commitment is the principal pillar of peace throughout the world. If that commitment becomes unreliable, the communist world would draw conclusions that would lead to our ruin and almost certainly to a catastrophic war."

Robert McNamara, who came eventually to doubt the wisdom of the war he had helped to shape, cited that warning of Rusk's as the basic reason for his, the President's, and the other advisers' decision for action: "I cannot overstate the impact our generation's experiences had on . . . all of us. We had lived through the years of war that resulted from the western powers not stopping the advance of Hitler when there still was time."

That was it: the lesson of Munich. World War II could have been prevented if only we had had the wit, the wisdom, and the fortitude to stop Hitler while there still was time. The relevance of that lesson was obvious: to avoid another war, communism, the new aggressive force bent on world domination, had to be stopped wherever it showed its aggressive face—and that face was clearly visible in Vietnam.

That's how a generation of leaders saw it. That's how Johnson saw it. He heard it from his trusted advisers, and he heard it from his gut. "I was staring at World War III."

All these years later, it's hard for a new generation to recapture—or perhaps even understand—that belief. All of Vietnam is under communist control today—but the dominoes did not fall; the juggernaut did not sweep through Southeast Asia, or endanger our security.

Did our stand in Vietnam count for anything? Did it contribute in any way to the ending of the Cold War? I don't pretend to know the answer, as once I thought I did. But I do know that Johnson died believing he had done what he had to do to prevent war, and that history would understand that. I hope it will.

The Presidential library, on the campus of the University of Texas in Austin, that houses his papers and bears his name is also part of his legacy. "It's all here, the story of our time, with the bark off," he said at the library's dedication, "for friend and foe alike to judge."

He meant it. He wanted all the papers opened for research as quickly as possible. He was impatient with the general if unspoken rule at the time that it took at least five years for the first group to be opened. "Let's cut that in half," he ordered.

And he was not at all sympathetic with the general rules for keeping papers closed. "You're being much too cautious," he said when he saw some of the candidates for closing. "I said [referring to his dedication speech] the bark's off. Now you're going to have me pick up the New York Times and read, 'Well, Johnson's got the bark still on.'" When he thought he saw signs we intended to go easy on him, he told me, "Good men have been trying to protect my reputation for 40 years, and not a damn one has succeeded. What makes you think you can?"

He insisted that there be a prominent exhibit in the museum on the controversies of the time, and he made his own contribution to it—a postcard from a man in California. He found it by plowing through a box of unfriendly correspondence himself. It read: "I demand that you as a gutless son-of-a-bitch resign as President of the United States."

All of this was at some variance with the reputation for secrecy and thin-skinnedness he had achieved as President. But it was real, and we took him at his word and began to build the library's reputation on that word.

We violated his instructions when we opened his telephone conversations. Those instructions from the grave were that the tapes be kept closed for 50 years after his death. With Lady Bird's support, we cut that short by about three decades. But we would not have done it had we not been so impressed by his early instruction to open everything immediately. As it happened, the release of the telephone conversations has had a decided effect—positive—on his reputation. Had he anticipated that, I doubt he would have imposed that 50-year restriction—or any restriction at all, for that matter.

When I left the directorship of the library after 30 years, following my time with him in the White House, I was asked by a reporter if I would miss standing in the shadow of a great man after so many years.

And now he's back. He's been gone 35 years—40 out of power—as he returns for the centennial observance when his record, in all its controversy and glory, will be spread out in programs and activities that try to capture him anew.

For me, for all of us still standing in his shadow, it's as if he had never left.

Harry Middleton was director of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum from its opening in 1971 until his retirement in 2002. Previously he was a reporter for the Associated Press, freelance writer, and assistant to President Johnson.