Sage Prophet or Loose Cannon?

Skilled Intelligence Officer in World War II

Foresaw Japan's Plans, but Annoyed Navy Brass

Summer 2008, Vol. 40, No. 2

By David A. Pfeiffer

Ellis Zacharias sipped on his dry martini as he matched poker skills with a group that included a young naval attaché with the Japanese embassy.

Zacharias, a naval intelligence officer posted in Washington in the 1920s, was not only playing poker but also trying to get the espionage-minded Japanese officer to let slip some information about his country's plans in the Pacific. He restricted himself to just the one martini in order to maintain his edge. This probing for information was a mutual exercise, usually involving shrewd questioning by both men as they played each hand.

Revealing only enough information to keep the conversation going, Zacharias could absorb what he heard over time while maintaining his friendship with the young Japanese officer, who had a reputation as a gambler.

Some years later, Zacharias would use information gathered this way to warn his superiors that Japan, by then on the march across the Pacific Rim, would launch a surprise attack on the United States in the Pacific—on a Sunday morning.

The Navy ignored his warnings. But early on December 7, 1941—a Sunday morning—Japan suddenly attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. It was an operation planned by Zacharias's old poker-playing partner, Isoroku Yamamoto, by then commander in chief of the Japanese fleet.

Zacharias's prediction of the Pearl Harbor attack was a product of his interest in intelligence, primarily in Japanese affairs, an area that was not held in the highest regard at the time. His 25 years in intelligence (out of 38 in the Navy) made him a colorful and controversial figure and were punctuated by clashes with superiors, unwelcome assignments, and failure to gain recognition that his record merited.

Ellis Zacharias was born in Jacksonville, Florida, on January 1, 1890. His parents, Aaron and Teresa (Budwig) Zacharias, were early settlers of Jacksonville, Aaron having arrived there shortly after the Civil War. Ellis, the youngest of five boys and two girls, was appointed to the Naval Academy in 1908. After graduating high in his class in June 1912 and having the distinction of being the only Jewish graduate of Annapolis for at least a 10-year period, Zacharias served on a variety of naval vessels. He served aboard the battleship USS Arkansas when that vessel transported President William Howard Taft to inspect the Panama Canal in October 1912, and during World War I, he was engineer officer of the cruiser Raleigh and gunnery officer on the cruiser Pittsburgh.

In 1920, Lieutenant Commander Zacharias, determined to make his mark in intelligence work, received orders to go to Tokyo. There he learned to speak Japanese fluently and became acquainted with many of the Japanese officers and government officials who were to control the country's fortunes in later years.

In Tokyo, Zacharias studied the craft of intelligence under the naval attaché to Japan, Capt. Edward Watson, a dynamic and resourceful officer. Watson was extremely popular with many Japanese naval officers who, according to Zacharias, were "mystified by his technique of telling them too much so that they could learn too little." In other words, he talked a lot without saying anything.

As Zacharias developed contacts and gathered information about Japanese attitudes toward arms limitations to be imposed on the land of the rising sun, he soon learned that many important figures in the Japanese military viewed the United States as a future enemy and therefore as an open adversary in the game of intelligence. He also became aware of certain inadequacies of the American intelligence-gathering apparatus in Japan, such as the lack of manpower, resources, and in particular, the lack of importance that American authorities placed on intelligence operations, particularly in Japan.

The most noteworthy event that occurred while Zacharias was stationed in Japan was the Yokohama earthquake of September 1923. From his vantage point on the harbor pier at Yokohama, he gained a rare insight into the Japanese character under extreme stress. He later described the scene: "From the first moment of crisis and horror it was the foreigners among the crowd who recovered from panic and started rescue efforts. The Japanese were captives of an amazing psychic inertia, completely incapable of grasping the situation. They seemed struck to absolute helplessness." After the earthquake had ceased, they went about their work with "an impassive indifference in the face of the destruction" around them. These early observations later proved extremely useful in 1945, when Zacharias, in a series of Japanese language radio broadcasts, attempted to persuade the Japanese high command to surrender.

In 1926 the assistant director of naval intelligence, Capt. William Galbraith, recognizing Zacharias's unusual interest in intelligence operations, brought him to Washington, D.C., for a six-month hitch in the Office of Naval Intelligence's (ONI) secret cryptanalysis unit. During this tour, Zacharias justified Galbraith's confidence by his thorough surveillance of Yamamoto.

After the Washington posting, Zacharias's career continued on the rise when, in 1927, he was assigned to the Asiatic Station as an intelligence officer specializing in cryptography. His new assignment was a choice one. Aboard the cruiser USS Marblehead, he headed the first comprehensive radio communication intercept unit, successfully monitoring, intercepting, and translating Japanese naval radio communications during training maneuvers. He considered the information gained during this assignment as "representing a long step forward in our positive intelligence against Japan." At this point, he regarded himself as an experienced intelligence officer, one of very few who embraced intelligence as a permanent assignment and career. He also considered himself a major cog in America's intelligence efforts in the Pacific.

In November 1928, Zacharias began the first of a pair of two-year tours as head of the Far East Division of the Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington. The available intelligence resources were modest—initially the entire division consisted of Zacharias and a secretary. Later, however, the staff increased as tensions rose following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. After three years at sea duty and a term teaching at the Naval War College, Zacharias returned to Washington in 1934 as head of the Far East Division. He soon found himself heavily involved in intelligence and counterintelligence activities against the Japanese.

The highlight of this period was the controversial Yamaguchi incident. In July 1935, Ellis and his wife, Claire, gave a dinner party for Japanese naval attaché Capt. Tamon Yamaguchi and his staff at their home in Washington. Yamaguchi and Zacharias were long-time friends and rivals, each having scored intelligence coups against the other. During the dinner, at Zacharias's direction, ONI operatives were carefully examining Yamaguchi's nearby apartment to determine whether he kept an electric cipher machine on his premises. The agents did find documents containing information about a Japanese cipher machine but no sign of the machine itself. The importance of this little caper, like many other facets of Zacharias's career, has been debated by historians over the years, but Zacharias himself claimed that here he had, at least partially, penetrated the Japanese espionage ring in the United States and temporarily impeded its functioning.

Through the years, even while on sea duty, Zacharias kept in constant touch with ONI personnel; indeed, he cultivated his contacts. A circle of enthusiastic intelligence experts who gravitated around him, including Cecil Coggins, A. H. McCollum, Henri Smith-Hutton, and Army Col. Sidney Mashbir. Rear Adm. Edwin Layton, the combat intelligence officer on Adm. Husband E. Kimmel's staff at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, later remarked that Zacharias was apparently "talent scouting in anticipation of achieving his ambition to be director of naval intelligence." This admittedly biased collection of officers considered Zacharias to be probably the foremost U.S. intelligence officer. Smith-Hutton commented more objectively that "he impressed me as being a very energetic officer, with many unusual ideas; perhaps slightly eccentric, but talkative and good company." Many of the naval officers and men who served under him at sea or in the intelligence offices ashore held Zacharias in great respect and even affection.

By 1940 the Japanese intelligence network in the United States had been reorganized and was growing furiously. Its task was made easier by the availability of information in the United States. A trip to the Government Printing Office to purchase government-produced publications usually yielded immense quantities of intelligence data concerning American defense capabilities. The large number of Japanese agents and the vast quantities of information available to them, however, had the unintended effect of reducing the quality and effectiveness of their intelligence operation. Accordingly, Zacharias believed that "it was a case of knowing too much and therefore understanding too little"—information overload. Other obstacles for Japanese intelligence agents concerned the immense size of the country and the fluid nature of its defense planning. But ONI still had concerns for security of vital information because, according to Zacharias, Americans occasionally talked too openly and the press revealed too much.

Just before finishing his tour of duty as District Intelligence Officer at the 11th Naval District in San Diego, California, Zacharias learned from a confidential informant of a Japanese scheme for a suicide air raid on an American naval base scheduled for October 17, 1940. The goal was to destroy at least four capital ships so as to create a more equitable ratio with the Japanese fleet. It was determined that the target ships were anchored at San Pedro, California, and they were immediately alerted to the danger. The incident did not occur, but it was becoming increasingly clear to Zacharias that Japan was moving vigorously toward a wartime stance as a result of the recent signing of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. The U.S. battleship force in the Pacific, in particular, was being regarded more and more as the chief hindrance to their plans for expansion.

Zacharias's suspicions further hardened after a February 7, 1941, conversation with Adm. Kichisaburo Nomura in San Francisco, who was en route to Washington to assume his post as Japanese ambassador to the United States. Zacharias and Nomura were old friends, having met in 1920 while Zacharias was stationed in Japan. Nomura was being sent to Washington in a final effort by the "peace party" in Japan to try to prevent a proposed American embargo on oil and other essential exports to Japan. Or this may have been a smoke screen to help shield war preparations since the "war party" knew Nomura was seen as a moderate by the Americans.

During what Zacharias termed an "amazingly frank" discussion with Nomura, the ambassador appeared to be deeply fearful of the growing power concentrated in the hands of the Japanese war extremists. Nomura believed that a conflict with the United States would ruin or destroy the Japanese empire, but he appeared resigned that such a war appeared to be inevitable, especially now after the signing of the Axis Pact.

His years monitoring Japanese fleet maneuvers, the "false alarm" of October 1940, and now the seriousness of the Nomura confidences convinced Zacharias that if the Japanese decided to initiate hostilities, a sneak attack on a U.S. fleet base would constitute the opening salvo. He was galvanized into action, determined to inform his superiors about his supposition.

Sometime between March 26 and 30, 1941, according to his later testimony at the hearings held by the Congressional Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, Captain Zacharias called on Admiral Kimmel, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, at his headquarters in Hawaii. In the course of their conversation, Zacharias testified, he told the admiral that if the Japanese decided to go to war, "it would begin with an air attack on our fleet on a weekend and probably on a Sunday morning; [also] the attack would be for the purpose of disabling four battleships." Zacharias added that the probable method of attack would be by aircraft flown from carriers, and it would emanate from north of the Hawaiian Islands because of the direction of the prevailing winds.

Kimmel asked how such an attack could be prevented, and Zacharias replied that "the only possible way of doing it would be to have a daily patrol out to 500 miles" to ensure that enemy ships were not lurking nearby. When Kimmel protested that he did not have either the manpower or the planes to do the job, Zacharias responded, "Well, Admiral, you better get them because that is what is coming." During the conversation, Zacharias added that sightings of Japanese submarines off Pearl Harbor were indications that an attack was imminent.

Even before this conversation, on February 18, Kimmel was worried about an attack. "I feel that a surprise attack is a possibility. We are taking immediate practical steps to minimize the damage inflicted and to ensure that the attacking force will pay." However, neither Kimmel nor Gen. Walter Short, Army commander in Hawaii, had enough aircraft to conduct regular and extensive patrols that could go out far enough to detect an attacking fleet.

It also turns out that Zacharias was not the only one who predicted a Japanese surprise attack. The air defense officers of the Army and Navy, Maj. Gen. Frederick Martin and Rear Adm. Patrick Bellinger, in a report dated March 31, predicted the likelihood of a surprise dawn attack on Oahu, probably on a Saturday or Sunday.

This meeting between Zacharias and Kimmel was later the subject of bitter debate. Zacharias claimed that the admiral "seemed interested" during the one-and-a-half-hour discussion, but Kimmel, under investigation for alleged incompetence at Pearl Harbor, later testified he had no memory of the conversation at all. Capt. W. W. "Poco" Smith, who also sat in during the alleged conversation, contradicted Zacharias by testifying that he was "absolutely positive" that there had been no mention of a possible air attack on Pearl Harbor. Smith further stated that it was a case of "clairvoyance operating in reverse." The issue became a case of Zacharias's word against Kimmel's and Smith's.

Zacharias's attempted indictment of Kimmel at the Pearl Harbor hearings for dereliction of duty or at least errors in judgment did nothing to enhance his popularity within the closed ranks in the Navy. It was another instance where his outspoken method of presenting his novel opinions and ideas branded him as an outcast in the Navy. He considered one of the greatest frustrations of his career to be his failure to convince his superiors of the inevitability of a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Zacharias repeated his warning about the attack in November of 1941 to Curtis B. Munson, an emissary of Adm. Harold Stark, chief of naval operations. Zacharias was then in command of the cruiser Salt Lake City, stationed at Pearl Harbor. Munson, who arrived in Hawaii with instructions to investigate the possibility of armed uprisings by Japanese agents on the West Coast and Hawaii in the event of war, sought out Zacharias because of his knowledge of Japan and its intelligence apparatus. Zacharias advised Munson that he could eliminate any fears of uprisings of Japanese residents in either locality. The first act of war would come as a surprise air attack, and the utmost secrecy necessary for its success would prevent any advance warning to the local Japanese populace. Besides, "the attack would conform to their (the Japanese) historical procedure, that of hitting before war was declared." Indeed, Japan had done that in 1894 and 1904.

Zacharias repeated his warning yet again at a dinner with Lorrin Thurston, editor of the Honolulu Advertiser and radio station KGU, on November 27. Ironically, unbeknownst to him, the Japanese strike force moved out on November 26. Zacharias added that, based upon historical Japanese decision-making procedures, when a third envoy arrived in Washington, "you can look for things to break immediately one way or another." As it turned out, a third peace envoy arrived in Washington on December 3.

When the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor occurred, Salt Lake City was in company with a task force returning to Hawaii after delivering fighter planes to marines on Wake Island. Zacharias got his chance to retaliate when on February 1, 1942, the Navy went on the offensive for the first time in the war with a series of raids on the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. Salt Lake City, with Zacharias in command, played a prominent part in the bombardment of the island of Wotje in the Marshalls, and for this action he received a letter of commendation. Later in that month, Salt Lake City shelled Wake Island. In April, she was one of the vessels protecting the aircraft carrier Hornet when the ship launched the Doolittle raid on Tokyo.

From September 1943 to October 1944, under Zacharias's command, the battleship New Mexico participated in the recapture of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. In June and July 1944, the battleship bombarded Tinian and Guam in the Mariana Islands. Zacharias was awarded a Gold Star in lieu of conferral of a second Legion of Merit for his outstanding performance in the Marianas. Zacharias's superiors at this time gave him outstanding fitness reports and recommended his promotion to admiral. Interestingly, the consensus of opinion among Zacharias's seagoing commanders was that Zach was a "brilliant ship driver" (ship captain) who only fancied himself as an excellent intelligence officer. It was his superiors who did not hold him in higher regard as an intelligence officer.

His sea tour over, Zacharias was assigned to the post of chief of staff to the commandant of the 11th Naval District from October 1944 to April 1945. In March 1945, while still in San Diego, Zacharias submitted a plan for psychological warfare against Japan to Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal. The proposal was based on his years studying the Japanese psyche (particularly during the 1923 earthquake), the information gained through formation of a psychological warfare branch in ONI during his tour as assistant director in 1942, and his observation of the increasing war weariness of Japan as evidenced by the appointment of known moderate Adm. Kantaro Suzuki as premier.

The plan proposed to render unnecessary an opposed American landing on the Japanese main islands by beaming radio broadcasts at Tokyo to weaken the will of Japan's high command and strengthening the hand of the peace party under the new premier. The goal was to bring about an unconditional surrender with the least possible loss of life. Zacharias believed that the Japanese wanted to "know the meaning of unconditional surrender and the fate we planned for Japan after its defeat" and might prove more compliant about conceding defeat. As expected, Zacharias's plan ran counter to the prevailing view among American military and political leaders that the Japanese were fanatically determined to fight to the finish and that their morale was practically unbreakable.

Secretary Forrestal approved the plan on March 19, entrusting Zacharias with the task of translating the program into action. Zacharias thought this assignment would be the culmination of his distinguished Navy career. He assembled a small group of Navy Japanese linguists, prepared the scripts, and recorded the broadcasts using the facilities of the Office of War Information and the Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C. The recordings were then sent by wire or airplane to San Francisco, from where they were beamed to Japan via shortwave radio so that Radio Tokyo could pick them up.

On May 8, shortly after President Harry Truman's announcement of the end of the war in Europe, Zacharias, identifying himself as the "official spokesman of the U.S. Government," delivered the first in a series of 18 radio broadcasts to the Japanese leadership explaining the concept of unconditional surrender. Zacharias emphasized that unconditional surrender was a military term signifying "the cessation of resistance and the yielding of arms." In his view, unconditional surrender meant the capitulation of the Japanese armed forces and not (necessarily) the end of the Japanese way of life. Zacharias proposed a lenient interpretation of the unconditional surrender doctrine in the hope that the Japanese would be persuaded to end hostilities promptly. He recalled his past associations with many of Japan's top leaders and their families in order to build their trust in his version of the consequences of unconditional surrender. But, of course, Zacharias was not in a position to execute policy, a fact undoubtedly not lost on his Japanese acquaintances.

The speeches were aimed at Japan's military, industrial, and political leaders who had the power to pressure the war party to end the war. Zacharias did not count on reaching the average Japanese by radio, since not all Japanese citizens had them. To get the message to the citizenry, propaganda leaflets were air-dropped on the Japanese cities.

Thereafter, top officials in the Office of War Information observed that "these messages produced much positive reaction in the general population of Japan and in several instances exhortations warning the Japanese people against the broadcasts have been intercepted by the Federal Communications Commission."

A later report stated that Prince Takamatsu, brother of the emperor, and other top Japanese officials believed that the broadcasts "provided the ammunition needed by the peace party to win out against those who wanted to continue the war to the bitter end." Here was evidence that the Zacharias broadcasts were reaching their targets.

Despite the seemingly positive Japanese reaction to Zacharias's interpretation of unconditional surrender, the President rejected it in early July, and Zacharias was ordered not to state on the air that the emperor would be retained. There was as yet little agreement in the President's cabinet as to a solid position to take regarding the status of the emperor or as to the proper time to make such a statement. Once again, Zacharias had been overruled, this time by the highest authority.

Undaunted, Zacharias was so convinced of his position that he sought to circumvent this rejection by writing an anonymous letter addressed to Premier Suzuki, which was printed in the Washington Post on July 21. In this letter, he suggested that the Japanese government formally request clarification of American intentions regarding the emperor. In a follow-up broadcast, Zacharias reminded the Japanese of their choices: virtual destruction and a dictated peace or unconditional surrender according to the Atlantic Charter, which maintained that Japan would receive not only "peace with honor" but preservation of the original Japanese empire and all its institutions, including the emperor. Zacharias, at this point, had clearly overstepped his bounds. By suggesting that the Japanese could obtain surrender terms according to the Atlantic Charter, he had ignored the President's order not to state that the emperor would be retained.

Almost immediately, the Navy forbade Zacharias from making any further broadcasts to Japan unless he was detailed to the Office of War Information, which was done. The official reason for Zacharias's transfer to OWI was that his mission had become more diplomatic than military in character. By July 26, he had been stripped of his "official spokesman" status and reassigned to OWI.

Meanwhile, according to Zacharias, his overture to the Japanese met with a hopeful response. On July 24, Dr. Kiyoshi Inouye, an outstanding authority on international relations who had been selected to give the Japanese response to his July 7 broadcast, indicated that Japan was willing to surrender unconditionally "provided that there were certain changes in the unconditional surrender formula" such as being assured that the Atlantic Charter applied to her. Zacharias took this as a signal that the Japanese wanted to begin negotiations, since it was delivered on the eve of the Potsdam Declaration, where the terms of unconditional surrender were clearly defined.

Inouye's remarks apparently also reflected the opinion of Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo. However, the official history prepared by Japan's Self Defense Agency states unequivocally that "while the Zacharias broadcasts attracted attention within the cloisters of the Foreign Ministry, which had no legal and little persuasive power to secure peace, they had no impact at all on the Imperial Army, the dominant political force in Japan."

To put it all in context, Inouye's statements occurred two days before the Potsdam Declaration was signed on July 26 and 13 days before the first atomic bomb was dropped on August 7. However, the President and the secretary of state believed that the July 24 message was a smoke screen to cover preparations for Operation Ketsu-Go, the Japanese plan for the defense of the home islands.

Despite his abrupt reassignment, Zacharias was awarded another Gold Star in lieu of a third Legion of Merit for his Japanese broadcasts. His plan did not secure the Japanese surrender itself, but it was probably the most successful venture into psychological warfare during World War II for the United States and undoubtedly played an noteworthy role in preparing the Japanese psyche for the inevitable surrender once the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

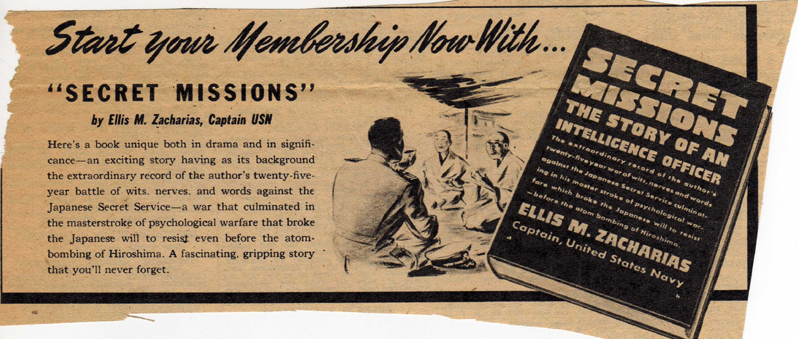

While on detail to OWI, Captain Zacharias submitted several lengthy reports and proposals, all designed to obtain a role for himself in the occupation of Japan. No action was taken. In addition, he made many public appearances as a representative of the Navy for the purposes of creating good will and to combat the current feeling that naval strength should be reduced and the armed services merged. He was commended by both the Navy (but probably not the Army) and public officials for his efforts. Otherwise frustrated and left with few remaining official duties, Zacharias used this postwar period to write his controversial autobiography, Secret Missions.

Secret Missions was published in mid-November 1946 to mixed reviews. Time called the book a good spy story and portrayed Zacharias as a man with multiple missions: one to plead the case for better and broader U.S. intelligence, two to blast away at U.S. naval stupidity, and three to make sure that nobody undervalued Ellis Zacharias. Even so, Time also conceded that Zacharias's general complaints about the Navy brass were "all too probably justified." The New York Times Book Review gave the work a positive review: "as a historical document it is one of the best of the items from which the story of the war will ultimately be written," albeit less sensational than advertised.

The Army and Navy Bulletin's review, not surprisingly, was not at all favorable. Most of Secret Missions was seen as "being about Captain Zacharias, a man in whose abilities and insights he has practically unlimited respect." The Bulletin chastised Zacharias further, saying that "he leaves nothing to the imagination, revealing the innermost secrets of war-time cryptanalysis." In short, the non-service reviewers were generally favorable, while the service journals were highly critical.

Zacharias was retired by the Navy and promoted to rear admiral at about the same time his book was published. After his retirement, Zacharias delivered an average of over 200 lectures a year on college campuses and to civic groups. He fervently wanted to educate the public on national security problems, the need for a strong national defense, and the continuing importance of intelligence activities, including a strong independent psychological warfare program. He advocated a hard line toward the Soviet Union and criticized past U.S. mistakes concerning the Soviets.

In addition to his lectures, Zacharias published another book, in collaboration with Ladislas Farago, in July 1950, after the beginning of the Korean War. Behind Closed Doors, a fictional account of the Cold War, conjectured that the Soviet Politburo would move against the United States by 1956, resulting in World War III.

Zacharias followed up his two books by composing and hosting a weekly radio series named Secret Missions in 1958 and a television series called Behind Closed Doors during 1959. Thus, to a degree, Zacharias accomplished in retirement what his Navy superiors had attempted to curtail—the free expression of his ideas openly and without topside interference. Through his books, speeches, and television and radio programs, Zacharias gained the public acclaim and the monetary rewards that eluded him in the Navy.

In sum, Zacharias will be remembered as having two primary intelligence successes in his career: his prediction of the Pearl Harbor attack and the propaganda broadcasts to Japan. Zacharias proved to be a brilliant but controversial intelligence officer fighting for what he believed to be right. Many times he refused to go along with his Navy superiors' policies but transcended official channels.

Beloved by his men but viewed with suspicion by his superiors, he assuredly was not viewed as a member of the Good Old Boys club in the U.S. Navy. The latter's view was that Zacharias was too much the self-proclaimed intelligence "expert" who sometimes overstepped his bounds with predictable consequences. He made enemies because he was, on many occasions, right at the expense of his superiors. He had been unable to convince the brass of the impending Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor during 1941; he was passed over for director of naval intelligence; his broadcasts to Japan were cut short; and he was not included in postwar intelligence operations. He failed to gain promotion to rear admiral while on active duty throughout World War II and was, instead, forced to retire. This is not surprising, since he was regarded as something of a loose cannon.

Ironically, some of the causes that Zacharias pioneered and fought for were in the end won by others. Despite the President's order forbidding Zacharias from commenting on the future of the emperor during his broadcasts, the Japanese ultimately agreed to an honorable peace and were allowed to keep their emperor. Also, largely due to Zacharias's labors as deputy director of naval intelligence, history has shown that ONI was able to maintain a strong operational intelligence network for the rest of the war.

Zacharias died of a heart attack at his summer home in New Hampshire in 1961. He was buried with full military honors as befitted his rank in Arlington Cemetery in an area especially reserved for high-ranking war heroes in the shadow of the Custis-Lee Mansion.

David A. Pfeiffer is an archivist with the Reference Section, Textual Archives Services Division, of the National Archives at College Park, where he specializes in transportation and State Department records. He is the author of Records Relating to North American Railroads, Reference Information Paper #91, and of the award-winning article "Bridging the Mississippi" in Summer 2004 Prologue. He is a great-nephew of Admiral Zacharias.

Notes on Sources

There are many sources on naval intelligence during World War II having to do with the buildup to Pearl Harbor and its aftermath. Among those used for this article are Rear Adm. Edwin T. Layton, And I Was There: Pearl Harbor and Midway—Breaking the Secrets; Michael Gannon, Pearl Harbor Betrayed: The True Story of a Man and a Nation Under Attack; Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor; and Jeffery M. Dorwart, Conflict of Duty: The U.S. Navy's Intelligence Dilemma, 1919–1945.

The decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan in 1945 and all the events leading up to it are covered in several sources including Richard B. Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire; Walter E. Schoenberger, Decision of Destiny; Robert J. C. Butow, Japan's Decision to Surrender, and Robert Lewin, The American Magic: Codes, Ciphers, and the Defeat of Japan.

Admiral Zacharias was the author of many publications, including his autobiography, Secret Missions: The Story of an Intelligence Officer, and a magazine article titled "Eighteen Words that Bagged Japan," published in the Saturday Evening Post, November 1945. Maria Wilhelm published a biography of Admiral Zacharias in 1967 titled The Man Who Watched the Rising Sun: The Story of Admiral Ellis M. Zacharias.

The transcript of the Hearings Before the Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, Congress of the United States, Seventy-Ninth Congress, was also helpful in the writing of this article.

Archival sources include materials from two record groups at the National Archives at College Park. In Record Group (RG) 208, Records of the Office of War Information, Deputy Director for Pacific Operations, General Correspondence of the Deputy Director, 1944–1945 (Entry 86), there is documentation concerning and copies of the Zacharias broadcasts to Japan. Also in RG 80, General Records of the Department of the Navy, there are the James Forrestal Papers (56-11-35), which include documentation concerning the broadcasts and Zacharias's detail to OWI.

Newspapers that published reviews of Secret Missions include the New York Herald Tribune, Time, the New York Times Book Review and the Army and Navy Bulletin.

Background information for this article was obtained from oral interviews with Admiral Zacharias's son, Capt. Jerrold M. Zacharias, USN (ret.), and his niece, Jean Zacharias Pfeiffer. Also, Captain Zacharias made available to me his collection of the admiral's personal papers that were discovered in recent years.