FDR: The President and the High School

Winter 2008, Vol. 40, No. 4

By Keith W. Olson

© 2008 by Keith W. Olson

Franklin D. Roosevelt maintained many interests. As President, he was the country's best known stamp collector. The Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum exhibits his lifelong love of ships and sailing through photographs, paintings, prints, and models. Throughout his life Roosevelt also maintained interests in the Dutch settlement of the Hudson Valley and in the history of Hyde Park, New York, his home village overlooking the Hudson River 85 miles north of New York City. Franklin, like his fifth cousin Theodore, descended from Claes Martenszen Rosenvelt, who arrived in New Amsterdam from Holland before the British took control of the city and changed its name to New York.

Dutch influence and local geography seemingly drew Roosevelt's attention to architecture and building materials. Stone walls lined roads and fields in Hyde Park township. Buildings in the mid-Hudson Valley testify to Roosevelt's affinity for native fieldstone construction and colonial Dutch architecture. Between 1936 and 1940 he commissioned six new post offices in fieldstone and Dutch colonial style, including one in Hyde Park. Roosevelt's interest in architecture reached its fullest expression in the design and building of his retreat, Top Cottage; in the construction of his presidential library in Hyde Park; and in the design and planning of the National Archives Building in Washington, DC.

In 1940 the Hyde Park school district's three new schools—Hyde Park Elementary, Violet Avenue Elementary, and Franklin D. Roosevelt High School—owed their fieldstone exterior appearance to his favorite building material and reflected his abiding interest and involvement with his home area.

Roosevelt was more than an "architectural consultant," to use more recent terminology. He merited the designation of architect and, therefore, joined Thomas Jefferson as one of the only two Presidents ever to design buildings. As an architect, however, Jefferson, vastly exceeded Roosevelt in accomplishment.

In 1915 Roosevelt expanded and renovated the family mansion, Springwood. The fieldstone used for additions came from the two stone walls that lined the drive from the house to the Albany Post Road. Twelve years later, FDR's mother financed the construction of a fieldstone library in Hyde Park Village and named it in honor of her husband, James. On his own land, approximately two miles east of the family home, FDR built two fieldstone cottages—Val-Kill for his wife, Eleanor, and Top Cottage for himself.

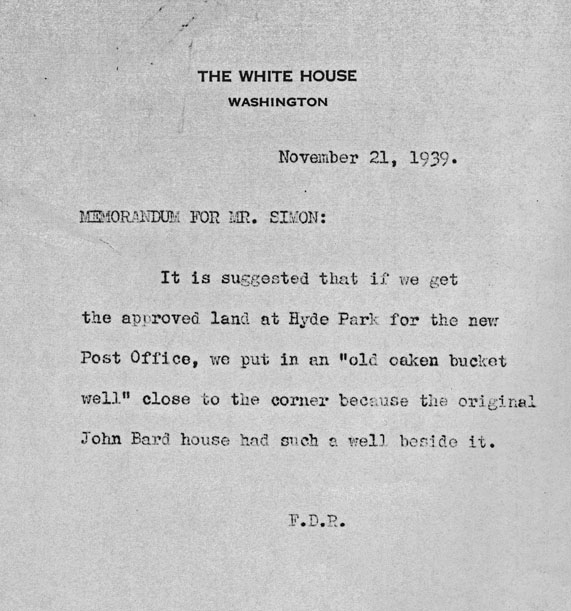

FDR commissioned the new Hyde Park post office and closely monitored its design and construction. In 1939 he met with the architect, Stanley Brown, and showed him a sketch of the Dr. John Bard house, which had stood on the site from colonial days until 1875. Brown and the President agreed that "the elevation and the ground plan" of the Bard house were excellent models for the post office. For the construction of the building, FDR recommended accepting an offer from Mrs. Walter Graeme Eliot to donate the stone walls on her farm, which had once been owned by the Bard family.

In 1941 FDR dedicated the country's first presidential library, funded by financial donations and gifts of fieldstone. As he had previously, FDR worked with the architect so that the library followed the colonial Dutch style that he so admired. The style and the fieldstone reflected both his family's Dutch ancestry and the heritage of the Dutch influence in the Hudson Valley.

FDR involved himself in most stages of the planning and construction of all three new schools, but especially the high school. In 1938 he read the school board's proposal to the Public Works Administration (PWA), which eventually financed 45 percent of the cost of the schools. FDR requested copies of the bids submitted by construction companies and asked for "photostat copies of architect's rendering of this school." When the bids on the high school opened, W. H. Kennedy, traveling engineer for the PWA, sent FDR a telegram stating that the low bidder was "thirteen thousand over the estimated cost."

The letter that Edwin A. Juckett wrote on July 1, 1939, further illustrated FDR's involvement: "This morning I took over the duties of the supervising principalship in the Hyde Park central school district. I am writing my first official letter to the first citizen of the district." Juckett further wrote that he "would appreciate an opportunity to consult with you on some long range planning and on the curriculum for the new buildings."

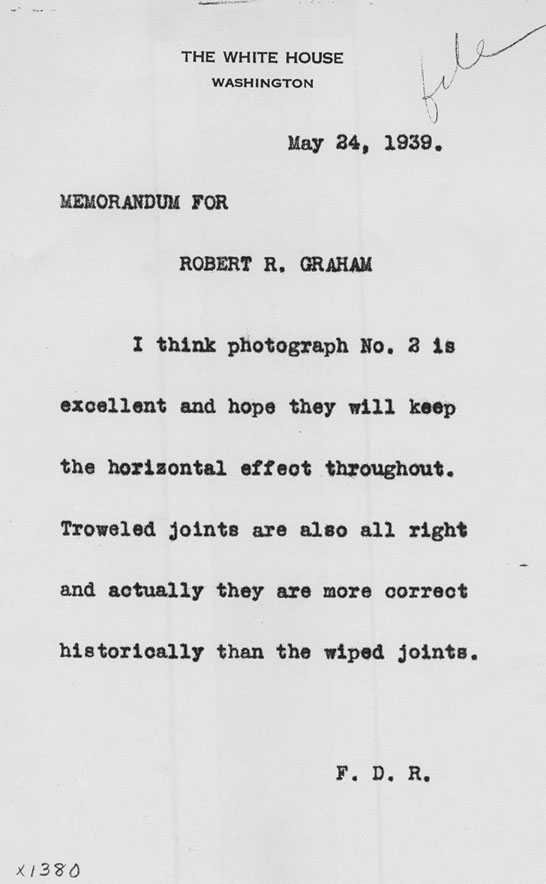

FDR's interest went far beyond early planning and curriculum. At various stages of construction, the President and the architect, Robert R. Graham, exchanged letters and met in person. Regarding stonework, FDR approved of troweled joints and added that "actually they are more correct historically than the wiped joints." The two men also agreed to paint the exterior woodwork "a shade slightly off white in a very light putty or ivory color."

FDR readily accepted the invitation to dedicate the new schools. On October 5, 1940, at 2:45 p.m., the President spoke for almost 20 minutes in front of the new Franklin D. Roosevelt High School. The National and Columbia Broadcasting Companies broadcast the speech on the radio, and newsreel cameras recorded the event. FDR related the dedication of the schools to Hyde Park, commented on the construction, and emphasized the importance of education. Finally, he connected the schools to his New Deal policies and to the world.

Juckett and other dignitaries sat behind FDR, as did Ben Haviland, whom FDR had invited because of their shared interest in local history and because the new high school stood on land that had once belonged to Haviland's farm.

FDR recalled for the audience that his father took pride in having helped to build the red brick school in the village that closed its doors when the new schools opened. As a boy, FDR added, he accompanied his father when he attended meetings of the board of education. "Personally," he continued, "I am happy also that, without any additional cost of materials, we have built these three buildings of the native stone of old Dutchess County." The stones, he pointed out, had for nearly two centuries first served "a useful purpose to the original settlers of this County as part of our famous stone walls." He praised the trustees for their "very rare foresight, having secured adequate acreage for the schools, enough for expansion in the century to come."

The new schools, FDR declared, symbolized two modern governmental functions, each of which was "more and more vital to the continuation of the thing we call democracy." The first was universal free education without government decrees controlling textbooks, teachers, and schools. "Tyranny hates and fears nothing more," he explained, "than the free exchange of ideas, the free play of the mind that comes from education."

The new schools also symbolized, according to FDR, "a new responsibility that our democracy has assumed as one of its major functions . . . to give work to many Americans who otherwise could not find work." He explained that local taxpayers and the federal government together paid for the schools and thereby contributed to the economy and morale of Hyde Park, with workers gaining increased self respect. FDR asserted with pride that in almost every county in the country similar projects dotted the landscape, such as schools, bridges, airports, sewer systems, water works, and hospitals. Such buildings, he believed, were gains in the well-being of the country and "for the defense of America as well."

When FDR spoke, he was in the middle of his campaign to win an unprecedented third term as President. The two symbols that he associated with the schools fit smoothly into the implementation of the New Deal programs and policies he had established since 1933. These projects, he maintained, helped knit together the country at a time when "emergencies . . . threaten the democracies of the world."

FDR's dedication speech integrated the role of schools into the context of Hyde Park, the New Deal, and the nation. He also celebrated the value of education, democracy, and history. As Hyde Park's first citizen, he blended into his talk several personal references. Although he spoke from a prepared draft of a text, which he had revised, he also extemporaneously deleted and added words, phrases, and sentences as he went along.

The President's speech attracted attention from beyond radio coverage. The October 6 issues of both the New York Times and the New York HeraldTribune started their stories on page one, printed the text of the speech, and included a photograph of FDR driving his famous blue Ford convertible with the school in the background. The Tribune's two-column-wide headline read, "Roosevelt Calls Free Education a Barrier Against Dictatorship." The first paragraph added that the President "defended heavy spending during his administration as a government responsibility and duty." Although FDR listed the speech as "non-political," the Times opened its article by pointing out that the President associated his New Deal with academic freedom, national well being, defense, and public works to provide jobs for unemployed workers.

The October 14 issue of Time magazine included several photographs about the Hyde Park speech and concluded that "the Roosevelt political magic was still at work—adroit and fluent as ever, he somehow managed to make Federal spending merely a matter of building schools, and to link free education with his administration." Time called the speech an "effective" answer to Republican presidential nominee "Wendell Willkie's charge that a continuation of New Deal policies meant a new economic system in the U.S."

The school dedication speech captured Roosevelt at his political best. No doubt the new fieldstone elementary schools, the high school that carried his name, and the setting in his beloved Hyde Park helped to make the occasion politically successful and, especially, personally satisfying.

The dedication may have been the climax, but it did not end FDR's involvement with the new schools. In December he sent the high school a Christmas tree from his own estate. The next March, Juckett invited FDR to speak at the high school's first commencement in June. FDR placed it in his engagement book. In May, however, he wrote to Juckett explaining that a cold had "laid [him] up for a couple of weeks" and that he had "to change or defer all my plans." Still, FDR added, if he were at Hyde Park, he would "come to the school and take part in the proceedings with a great deal of pleasure." The tentative program listed his name, but another cold kept him in Washington. In the midst of their correspondence about the commencement, Juckett wrote, "It will interest you to know that we received our high school charter. . . . We received the highest possible classification."

No doubt the news interested and pleased FDR, but growing war clouds during the late summer and autumn of 1941 and U.S. entry into World War II in December meant that he could not continue his once-close involvement with the high school.

In April 1945, less than a month before the war ended in Europe, FDR died. In June 1945 Eleanor Roosevelt, the President's widow, gave the commencement address at Roosevelt High School, a fitting tribute to her husband's association with the school that bore his name, reflected his architectural interest, and exemplified his deep attachment to his native Hyde Park.

Note on Sources

I am indebted to and thank Richard Montague for comments and encouragement. An earlier, shorter version of this story appeared in Forty-Niner, a newsletter published by FDR High School, Class of 1949, vol. 2 (Spring 2006).

Correspondence and speeches of President Franklin D. Roosevelt are housed at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, NY.

The construction of the Hyde Park post office is noted in FDR's letters to Helen Reynolds, November 1, 1939, President's Personal File (PPF) 234, and to Louis A. Simon, December 21, 1939, PPF 1853.

Correspondence throughout 1939 with W. H. Kennedy, Edwin Juckett, and Robert Graham about the construction of the schools, as well as FDR's exchange with Juckett in 1941 concerning the high school's first commencement ceremony is also in PPF 1853.

FDR's speech at the dedication and the revisions he made during delivery are found in box 1310, Master Speech File.

Keith W. Olson is professor emeritus at the University of Maryland, College Park. He now lives in Shelburne, Vermont, and is a lecturer at the University of Vermont. His research focuses on 20th-century presidential history. In May 2008 he presented a paper, "John F. Kennedy and Vietnam: The Preponderance of Evidence," at the British Association for American Studies Conference, University of Edinburgh.