Escorting a Presidency into History

NARA’s Role in a White House Transition

Winter 2008, Vol. 40, No. 4

By Nancy Kegan Smith

The long season of presidential primaries is over, the fall campaigns have rushed by, and the voters have decided who is to be the next President of the United States.

As the new presidential administration prepares for its inauguration on January 20, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is busy with another one of its unheralded jobs—planning for the transfer of hundreds of millions of textual, electronic, and audiovisual records, and tens of thousands of presidential and vice presidential gifts.

It's something that happens every four or eight years—and sometimes when it's least expected.

NARA is assisting in the presidential transition by ensuring the safe, smooth, and timely move of presidential and vice presidential records and artifacts from the outgoing George W. Bush administration into the legal custody of the National Archives at exactly 12 noon on January 20, 2009.

That's when NARA will finish its job of safely moving and tracking these historical items from Washington, DC, to the temporary facility NARA rents, which is near the final site of the outgoing President's library. In the case of President George W. Bush, the library will be built on the campus of Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas.

NARA does not move personal possessions of the President and the First Lady. Rather, NARA moves the wealth of materials documenting the inner workings of the government at its highest policy level that historians will for decades mine as they write and judge the history of our times.

Preserved by NARA in the presidential libraries will be the records of the tragedies, the problems, the successes, and the evolution of policies that affect the nation and the world during the presidential administration. The presidential collections being moved document the most personal and private thoughts and feelings of a President to the most formal foreign policy memorandums on presidential decision-making. The records include the classified files of the National Security Council as well as the files documenting domestic issues, audiovisual files, and the First Lady's files.

Presidential gifts that are accepted on behalf of the United States are part of the move and include a range of objects that have been received from foreign governments or the American people and foreign citizenry. From the Reagan presidency on, NARA has also been moving electronic records, which means transferring hundreds of millions of documents stored on many different electronic systems to NARA electronic systems.

NARA does not always have the luxury of months, even years, of planning for this important transition. First-term Presidents who fail to win reelection have no interest in talking about a transition when they expect to be in the White House another four years. When there is an unexpected event, such as President John F. Kennedy's assassination or President Richard M. Nixon's resignation from the presidency and the subsequent seizure of his papers by the government, the process of the move becomes even more challenging.

While a successful move of presidential and vice presidential records and artifacts sounds simple on its face, it is a complex job that really starts at the very beginning of an incoming presidency. Facilitating a smooth transition of the holdings of the outgoing presidential administration to NARA so that they can be preserved for posterity involves careful planning and coordination with many different agencies.

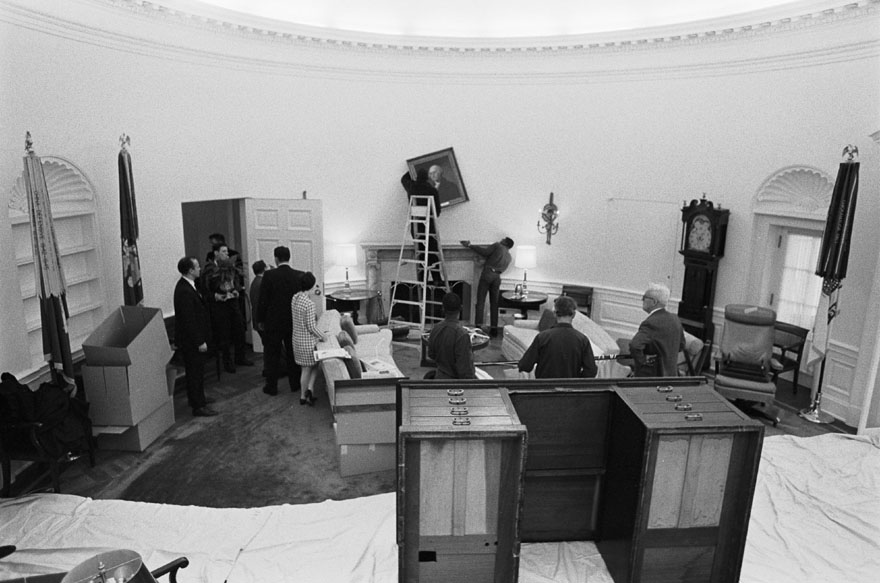

The Transition of Power—Moving One President Out

While NARA is the agency tasked with moving the incumbent President's records and artifacts, other government agencies provide assistance and work on different parts of the transition. The move is done in close conjunction and cooperation with many White House and vice presidential staff and offices, and also with the Department of Defense (DoD). Because all records and artifacts that are moved before the end of the presidency are still in the President's or Vice President's control, NARA must receive White House approval to start moving records as early as possible.

The planning for a move is most sensitive when a President is defeated after one term. A President running for reelection is not interested in having his staff work with NARA to plan for a transition. After defeat, there are fewer than three months to complete the move. In the case of a two-term President who is leaving office, we can begin moving records as soon as the temporary library site is ready to receive the records, which is usually sometime in late fall before the election. It is crucial that NARA, with DoD assistance, begin these moves months in advance, because the volume and complexity of these moves cannot be handled in the last few days or weeks of a presidential administration.NARA works with White House and vice presidential counsels, the White House Office of Records Management, the National Security Council, the White House Gifts Office, and other White House offices and the Office of the Vice President to receive approval to move early and to coordinate on what records and artifacts can move when. Additionally, throughout the presidential administration, these offices have worked to establish initial control and arrangement over the records and artifacts, provide preliminary descriptions at the folder, box, or artifact level, and to ready these materials for eventual transfer to NARA.

At the outset of a presidential administration, NARA begins preparing for the eventual move of records by offering the White House courtesy storage for the artifacts and records that do not need to be physically stored in the White House compound. Courtesy storage, offered to Presidents and Vice Presidents, means that the records are in the physical possession of NARA until legal custody transfers to the Archivist of the United States. The incumbent President and Vice President maintain legal custody over the records and artifacts during their terms.

While the records are in courtesy storage, NARA's Presidential Materials Staff provides reference service to the incumbent and returns the records to the White House, if requested, in a one-hour turnaround time, 24 hours a day. The records, gifts, and historical materials in courtesy storage are made available only to the White House as requested by designated Offices for reference. Boxes of textual records in courtesy storage remain sealed while in NARA's physical possession. NARA's Presidential Materials curatorial staff stores the artifacts, ensures that museum standards are met, and assists the White House on artifact loans. NARA's courtesy storage of records and artifacts significantly reduces the volume of material that needs to be transferred from the White House during the final months of an administration.

The Beginning of NARA's Involvement with Presidential Moves

Before the National Archives was founded in 1934, presidential collections (which, until 1981, were the personal private property of the President) were moved in a variety of ways. Sometimes significant parts of these collections were sold or scattered.

The earliest collections were quite small. When President George Washington left office, several wagons took his papers to Mount Vernon, where he could review them in his study.1

NARA's role in moving presidential collections began in 1939, when Congress accepted Franklin Delano Roosevelt's gift not only of land and the first presidential library building, but also of his presidential papers and other historical materials, for the establishment of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York. In exchange for the gift, the National Archives, which had been established only five years earlier, agreed to staff and run the library and make these materials available to the public.

Although NARA has a presidential library for President Herbert Hoover, the National Archives was not involved in the initial move of the Hoover papers and artifacts. Hoover transferred his presidential papers to either his office at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University in California or his New York office. In 1960 Hoover decided to deed his papers to the National Archives and the agency assisted with the move of his presidential materials from both locations to his new library in West Branch, Iowa.2

In 1955 Congress passed the Presidential Libraries Act (amended in 1986), which codified the system of presidential libraries. Today, there are 12 libraries that are part of the National Archives and administered by NARA's Office of Presidential Libraries, from Hoover through President William J. Clinton, with the future George W. Bush Library soon to join this system.

The Presidential Records Act of 1978 changed the legal ownership of the official records of the President and Vice President from private to public (starting in 1981 upon the inauguration of President Ronald Reagan) and defined that the Archivist would assume the legal ownership, custody, and responsibility for these records immediately at the end of the last term of the administration.

The Transfer of Power—Moving One President Out

Every move of presidential records and artifacts is different, due both to the ever increasing volumes and complexities of record types and to how and when the President leaves office. The constant in all presidential moves is that NARA has carefully controlled, packed, and inventoried these records and artifacts during transfer so that these materials can be quickly located if they are needed back before the end of the administration.

The transfer of Roosevelt's papers and artifacts began in the middle of his presidency because his library was completed in the summer of 1940. The first shipment began on August 14, 1940, and included some of his White House papers and gifts. (Indeed, FDR used his office in the library whenever he was at his home in Hyde Park from 1940 until his death.) During this early period, the White House materials were even sent to the National Archives for fumigation (clearly an indication that the White House had a pest problem before the Truman remodeling!), and then would be crated and sent to Hyde Park. Large shipments would go by truck, with smaller shipments often being sent on the President's train.

After Roosevelt's death, the White House moved the rest of the Roosevelt files (with the exception of the Map Room files, which dealt with World War II and were needed by President Harry S. Truman) to the National Archives, where they were held while the FDR estate and legal disposition of the papers was resolved. The National Archives started transferring the papers to Hyde Park in December 1946. By the end of 1947, all the Roosevelt files, which consisted of approximately 17 million pages, were at the library; the Map Room papers came in 1951 on Truman's specific order.3

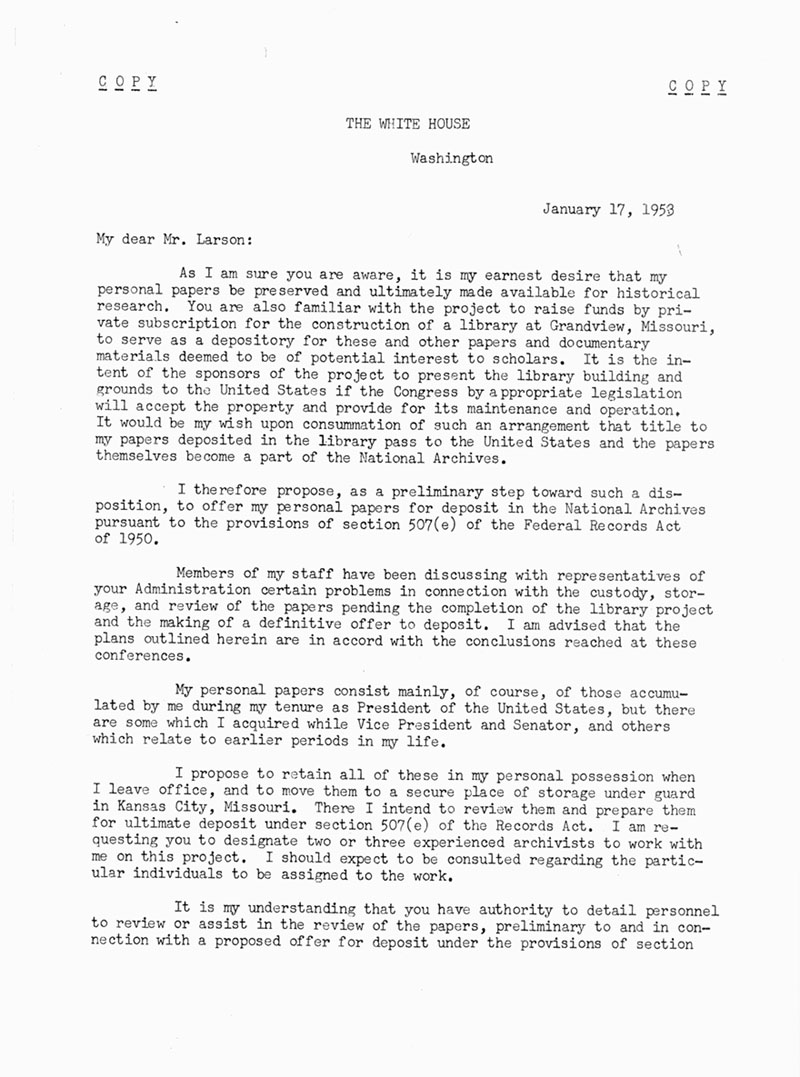

In January 1953, Truman's own papers were packed onto 12 Army trucks and driven to secure storage in Kansas City, Missouri. Since presidential papers were treated as the President's private property at this time, Truman did not immediately give his papers to the government but stated his intention to do so once the Truman Library was built. At Truman's request, the government assigned several archivists to work on his materials. In 1957 Truman officially donated his papers to the National Archives for deposit in the new Truman Library.4

Moving President Dwight D. Eisenhower's papers and artifacts occurred in several stages. All of his papers left the White House in January 1961. The Army guard and the trucks carrying the presidential collection arrived in Abilene, Kansas, at the Eisenhower Library site in late January. Papers designated by Eisenhower as his personal collection went to his office in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, until he finished using them for his memoirs. These papers were later sent to the library in Abilene. Some presidential artifacts had been sent to the museum (at this time privately owned by the Eisenhower Foundation) during his presidency, with the bulk going by truck at the end of the administration. The museum became part of the National Archives Eisenhower Center in 1966.5

The most unexpected and tragic presidential move occurred with the assassination of President Kennedy. After the President's death, all of the Kennedy administration's records were moved to the National Archives Building in downtown Washington. A "Kennedy Library" staff was hired and worked out of the Office of Presidential Libraries. Attorney General Robert Kennedy, working in the Justice Department building across the street from the Archives, served as the de facto library director. The Kennedy Library staff and papers of the administration were moved to Boston more than two years later, and the audiovisual collections were not transferred until 1980.6

President Lyndon B. Johnson announced in 1965 that his presidential library would be at the University of Texas. Accordingly, the move of the Johnson materials began a few months before he was to leave office, and most of the materials were moved in January 1969 up to inauguration day. Even though this was a planned move, the Archives faced the common and persistent problem it still faces today: Because the White House staff feel the need for immediate access to their files, they are hesitant for these materials to be moved out of the Washington area before the last possible moment. Consequently, once a night, from 9 p.m. to one or two o'clock in the morning, a truck would come to the White House to pack up and move a total of approximately 35 million pages.7

A very unusual move occurred when President Nixon resigned in August of 1974. At the time he resigned, his presidential papers were estimated to consist of approximately 42 million pages. Shortly after the resignation, Congress passed the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act to seize his presidential materials, particularly the Watergate tapes, and place them in the National Archives. Nixon sued the government, claiming that these were his private property, as had been the case for every prior President since George Washington. The ongoing litigation over who owned and controlled the Nixon materials was finally resolved in the government's favor in 1977 by the Supreme Court.

The White House materials were moved to a storage area underneath a staircase of the Old Executive Office Building (OEOB) and stayed there for many months, with little being done. Few of the Ford White House staff even realized that the Nixon materials were actually being stored in the OEOB. Finally, in 1975, the materials were moved in a military caravan to Suitland, Maryland, and then moved again to the 18th level of the National Archives Building when it was considered secure enough to hold them.8

Nixon's materials are now in both the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California, which the National Archives accepted from a private foundation last year, and at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, where all of Nixon's materials were held until NARA took over the Yorba Linda facility. Eventually, all the Nixon collection will be moved to the California library.

Planning for the move of President Ford's papers did not even begin until December 14, 1976, when President Ford signed a deed of gift for his papers and announced his intention to build a library. Since the Ford White House had dealt with the Nixon papers issues from the outset of the presidency, the Archives was not given an active presence in the White House until the very end of the administration.

It was only in the first week of January that Archives staff were able to work in the White House complex with the White House Central Files staff to survey offices on the volume of material, establish staging areas, begin the collection, palletizing, and removal of materials. For two weeks, trucks were loaded with pallets of presidential materials and driven to Andrews Air Force Base, where they were parked and kept under guard. The last truck, containing National Security Council papers, was loaded on January 19. The convoy consisting of nine semitrailer trucks departed Andrews AFB, with military escort, on January 20, 1977, arriving in the evening in Ann Arbor, Michigan, site of the Ford Library.9

Another difficult move was in 1980. When President Jimmy Carter was defeated after one term, the Archives did not know whether or where the presidential library was going to be built or when we could begin moving the materials. Because the Archives has only about 77 days to complete the move of one President out of the White House before the new chief executive moves in, time is of the essence. Finally, in mid-December, the Archives got the approval to move and learned that presidential library would be built in Atlanta. This was also the last presidential transition that was moved entirely by trucks.

Moves of Records from Reagan Forward

The Reagan transition in 1989 was the first one covered by the Presidential Records Act of 1978. No longer would the Archives need to wait for the President to donate his papers. Now, legal custody of the President's records automatically transferred to NARA at noon on the last day of the administration. Reagan's was also the first complete two-term Presidency in 30 years, which resulted in the largest number of records and artifacts ever to be moved—approximately 43 million pages, including approximately 8 million pages of classified records, and tens of thousands of artifacts. The Reagan administration was also the first to use e-mail, most of which were created on a highly classified National Security Council system.

The transition of a two-term President gave NARA more time to plan and ensure better archival control than in previous moves. The Archives also initiated the use of a computer system to track the movement of the records and artifacts. This system was able to control each box during transfer and preassign each box to a shelf location at its destination at the temporary project site in California.

The mode of transportation also changed during this move. Because of the volume of records and artifacts to be moved and the distance they had to go, it was decided that air transport would be best because it minimized the time and made security easier.

NARA arranged for the Federal Protective Service and the California Highway Patrol to provide security for the trucks that took the materials to and from the air bases, and NARA personnel provided coverage for the materials during transport. The artifacts were sent to the National Archives Federal Records Center at Laguna Niguel, while the records went to the temporary library site in West Los Angeles.10

The Reagan move established the model that was followed in moving the presidential records and artifacts of the George H. W. Bush and Clinton administrations. Both the Bush and Clinton moves used a combination of trucks and the C-5 transport airplanes.

The move of President George H. W. Bush's records, like those of Ford and Carter, was done in a very compressed time period because he failed to win reelection. NARA used soldiers from Fort Hood, Texas, to shelve records into the temporary facility, a converted bowling alley approximately three miles from the permanent site on the campus of Texas A&M University. Many of the soldiers had served in Desert Shield and Desert Storm and were enthusiastic to help move the former President's records. The first shipments (two C-5 cargo planes of records and artifacts) reached the Bush Library on January 15, 1993, after passing through several small Texas towns where the local marshal stood sentinel and made sure that traffic did not hold the convoy up at 4 a.m. By mid-morning the records were shelved properly, without exception, as teams of soldiers raced each other to see who could shelve the most. The entire process was repeated on January 21, one day after the end of the administration.11

The Clinton move was the largest one ever, involving approximately 75 million pages, approximately 75,000 artifacts, and millions of audiovisual materials. This transition also involved a large amount of electronic records systems, and as a result, NARA's information technology staff increasingly became a key part of the presidential move. Because this was a two-term presidency, planning began early. For the first time, NARA hired Clinton Library staff well before the transition, beginning in November of 1997 to ensure that the staff were trained at the time the records were transferred to NARA.

Even though this was a planned move, NARA faced the traditional hesitancy of a President and his staff to let go of their materials. Nonetheless, the first C-5 left for Little Rock in late November 2000. By the time it was over, NARA staff, working with the Pentagon, had moved approximately 67,000 feet of material (totaling an estimated 835 tons) to the temporary facility in Little Rock. This effort entailed eight flights of C-5 aircraft and countless hours of palletizing, loading, unloading, and shelving of boxes by both NARA and DoD personnel at the White House complex, the National Archives Building, Andrews Air Force Base, the Little Rock Air Force Base, and the Clinton Library facility.

Again in this last year of a two-term administration, NARA staff, with DoD assistance, are working on a presidential move. While the inaugural balls are getting set up, there are so many dedicated White House, NARA, DOD, and other agency staff pulling together, working late into the night and early in the morning, to facilitate a smooth transition of power from one President to the next and to preserve the history of the outgoing presidential administration.

Nancy Kegan Smith is director of the Presidential Materials Staff at the National Archives and Records Administration. She has worked for the National Archives and Records Administration from 1973 until the present. She started working as an archivist at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and in 1989 moved to Washington, DC, to work for the Office of Presidential Libraries and later the Office of General Counsel on Presidential access issues.

Notes

1. Bruce Oudes, From the President : Richard Nixon's Secret Files (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), p. xvii.

2. Conversation with Tim Walch, director of the Hoover Library, on October 14, 2008.

3. E-mail from Robert Clark, supervisory archivist at the FDR Library, to author, Sept. 8, 2008.

4. E-mail from Ray Geselbracht, archivist at the Truman Library, to author, Sept. 8, 2008. Because the Archives had by then been merged into the General Services Administration, Truman's deed of gift was accepted by the Administrator of General Services instead of the Archivist of the United States.

5. Telephone conversation with John Wickman, former director of the Eisenhower Library, on Oct. 14, 2008.

6. E-mail from John Fawcett, former head of the Office of Presidential Libraries, to author, Sept. 11, 2008.

7. E-mail from Tina Houston, assistant director of the Johnson Library, to author, Sept. 8, 2008.

8. "Hearings Before the Committee on Government Operations of the United States Senate," 94th Congress, First Session, May 13, 1975, GPO publication, pp. 92 and 263. Additional information came from an e-mail sent to the author on Sept. 22, 2008, from Steven Garfinkel, former National Archives General Counsel.

9. E-mail from David Horrocks, supervisory archivist at the Ford Library to author, Oct. 9, 2008.

10. Binder "Presidential Transition of Ronald Reagan, 1989," Apr. 28, 1989, memo of John Fawcett, Assistant Archivist for Presidential Libraries on Transfer of Reagan Presidential Records from Washington to California, White House Office of Records Mangement Subject File, FG001-04, Presidential Transition.

11. E-mail from Warren Finch, director of the Bush Library, to author, Oct. 16, 2008.