In Freedom’s Shadow

The Reconstruction Legacy of Renty Franklin Greaves of Beaufort County, South Carolina

Fall 2010, Vol. 42, No. 3

By Giselle White-Perry

© 2010 by Giselle White-Perry

The period in American history known as "Reconstruction" began a social revolution that changed the South forever.

For 14 years (1863–1877), persons of African descent once held in chattel slavery worked and served next to former slaveholders to reunite a divided society based on the principles espoused in the United States Constitution. Nowhere else in the South did blacks become the dominant force in gaining equality through self-governance than in South Carolina, the only state to have a black majority in the legislature during Reconstruction. Nowhere in South Carolina did blacks dominate the political scene than in Beaufort County.

Men such as Robert Smalls, Jonathan Jasper Wright, William J. Whipper, Julius I. Washington, and Thomas E. Miller were at the forefront at the national and state levels. Many others were obscure officeholders at the local level. They were justices of the peace, school board commissioners, county commissioners, clerks of court, constables, auditors, board of education and city council members, registrars, coroners, magistrates, and sheriffs.

Renty Franklin Greaves was one of those men. While he did not achieve the fame of his counterparts, his story represents the lives of many African American leaders who remain in the shadows of history during Reconstruction and beyond. In records at the National Archives, he is simply described as "some important county official in Beaufort County." A former slave, he was elevated to a place in American political history as a local public officeholder, only a few years after the demise of slavery.

Telling Greaves's story challenges the common assumption that the majority of black officeholders have been identified, and no information is available other than name and the office held. It shows the wealth of information that can be gleaned from records about African Americans living in the 19th century, particularly in the South Carolina Sea Islands.

Cultural and social conditions were distinctly different for blacks in the South Carolina Sea Islands, particularly Beaufort County, from the very beginning of the war. On November 7, 1861, when the Union fleet sailed into Port Royal Sound and captured Fort Walker on Hilton Head Island, nearby slaveholders fled inland. The enslaved saw an opportunity to liberate themselves, and they seized it. They left the farms and plantations in pursuit of freedom and headed for refuge in nearby Union-held territory.

By the time the Emancipation Proclamation became effective on January 1, 1863, they had begun to establish the foundation for political mobilization through kinship networks, churches, and schools. In this climate, Greaves emerged as a local businessman, politician, and public servant. Despite, or because of, the controversy that seemed to be his constant companion, he managed to rise from slavery to positions of local prominence.

Greaves's Early Years as Slave, Soldier

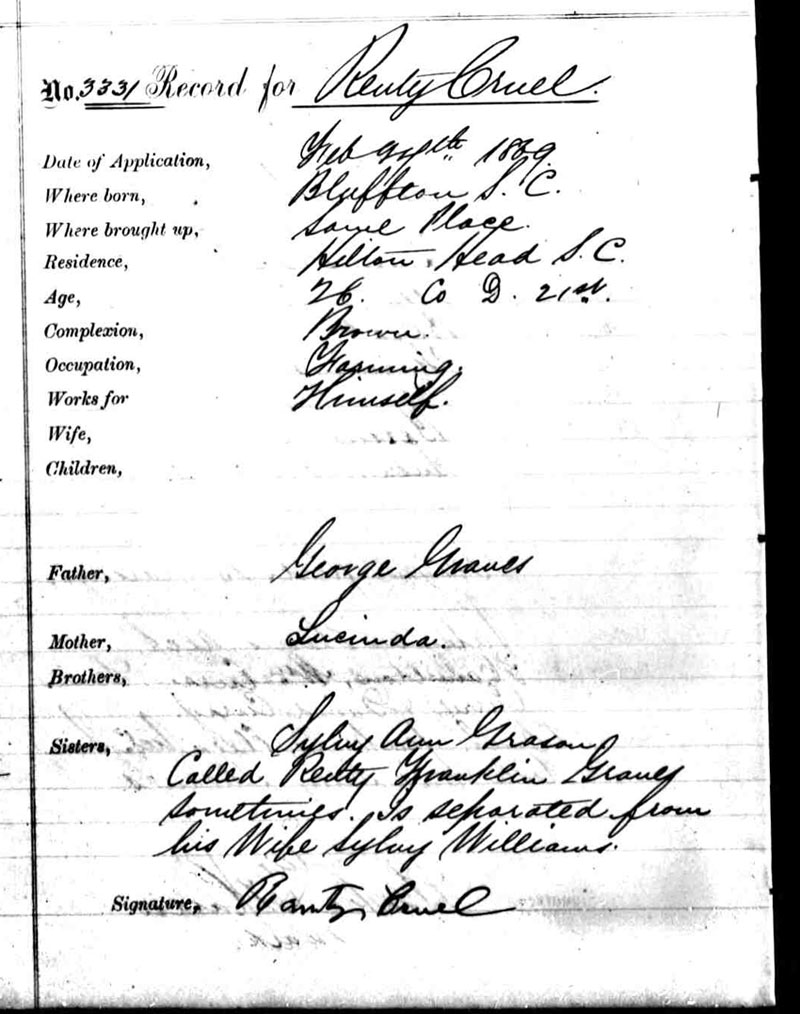

Greaves was born about 1844 on Linden Place on the May River (near Bluffton, South Carolina), the son of George and Lucinda Greaves and brother of Sylvia. He and his family were the property of Nathaniel P[ierce] Crowell, formerly of New Jersey. Crowell first appears in the U.S. census for Beaufort County in 1830 as the owner of 90 slaves. By the 1860 census, he was 66 years old with real estate valued at $15,000, a personal estate valued at $68,000, and 56 slaves.

According to the 1860 agricultural schedule, Crowell had 310 acres of improved land and 590 acres of unimproved land. The area surrounding the Crowell plantation was also a site for the production of salt, a vital commodity in the war effort. Federal troops engaged in several armed expeditions on the May River for the purpose of destroying salt works.

Not much is known about how much Greaves and his family knew of the impending war and opportunity for freedom. Linden Place was near Bluffton, the center of secession discussion before the war, and there must have been rumors floating about.

By the time he was 18, Greaves and his family had found refuge at Fort Walker on Hilton Head. They were among those who came to be known as "contraband of war." Despite reaching Union-held territory, their official status was uncertain. The U.S. government was reluctant to acknowledge them as free people but did not want them returned to the control of their Rebel masters. Over time, housing evolved from tents to crowded barracks to a town on the Fish Haul site near Drayton Hall plantation. By March 1863, the town of Mitchelville was established to provide the newly freed persons the opportunity to practice self-governance. By 1865, the government reported 1,500 people living in Mitchelville.

The land on which Mitchelville was located was eventually redeemed by the Drayton family. This created a new source of conflict between the original landowners, the U.S. government, and the new landowners—the freedmen. Greaves and several other residents resisted by filing a claim to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service for improvements made on the property. However, no evidence has been found to indicate whether the claim was awarded.

Greaves's fighting spirit was not reflected in his exploits as a solider but in his determination to be released from his military obligation. He enlisted on June 24, 1863, joining C and E Companies of the Third South Carolina Infantry, which was later reorganized to Company D, 21st United States Colored Infantry. He served in the military for a little over a year before being discharged for medical reasons on August 16, 1864.

Greaves claimed to have been coerced into entering military service by friends and family. In fact, he said they came and got him in the middle of the night to sign up. He gave in and agreed. His story of the events surrounding his enlistment coincide with those who claim that while some volunteered, others were forced into service against their will. He was enrolled under the name of his last slave owner: "Renty Crowell/Cruel."

For the last four months of his military service he was not able to do any physical labor, so he clerked in a New York regiment for a sutler named Whitfield. A regimental sutler sold a number of food and personal items that the Army did not provide for soldiers. As clerk, he would have been expected to perform such clerical tasks as keeping records, assisting with correspondence, and the like. Apparently Greaves already knew how to read and write. Upon his discharge from the Army, he returned to Hilton Head, where he was engaged in a variety of enterprises.

The Reconstruction Years: Getting Land and Education

Two issues were foremost in the minds of freedmen before, during, and after Reconstruction: education and land. Education was described as a grassroots effort as there were limited resources; schools were often built on land purchased by the community. School teaching was sometimes a dangerous profession as teachers of both races could expect to be humiliated and whipped or murdered, and schoolhouses were frequently burned. However, Klan-style acts of vigilantism were less common in areas like Beaufort County because the black population heavily outnumbered the white by at least twofold.

Because Greaves was literate, it is not surprising to discover that schoolteacher was on his long list of occupations. However, teaching school was not a lifetime commitment; he abandoned it after a short period for more lucrative pursuits. He was able to parlay his skills and abilities into achieving the competing goal of most freedmen—land ownership.

Political leaders wanted to make land available for freedmen to purchase at a reasonable price. A variety of strategies for how to distribute land were proposed and implemented to a limited degree. For freedmen living in most regions in South Carolina, the hope and promise of land ownership remained elusive. However, by 1890, three-fourths of the land was owned by blacks. In this climate, Greaves was able to rise to a level on the edges of the higher social strata. Black government officials in Columbia, Beaufort, and Georgetown were said to enjoy an elegant standard of living similar to that of Charleston tradesmen.

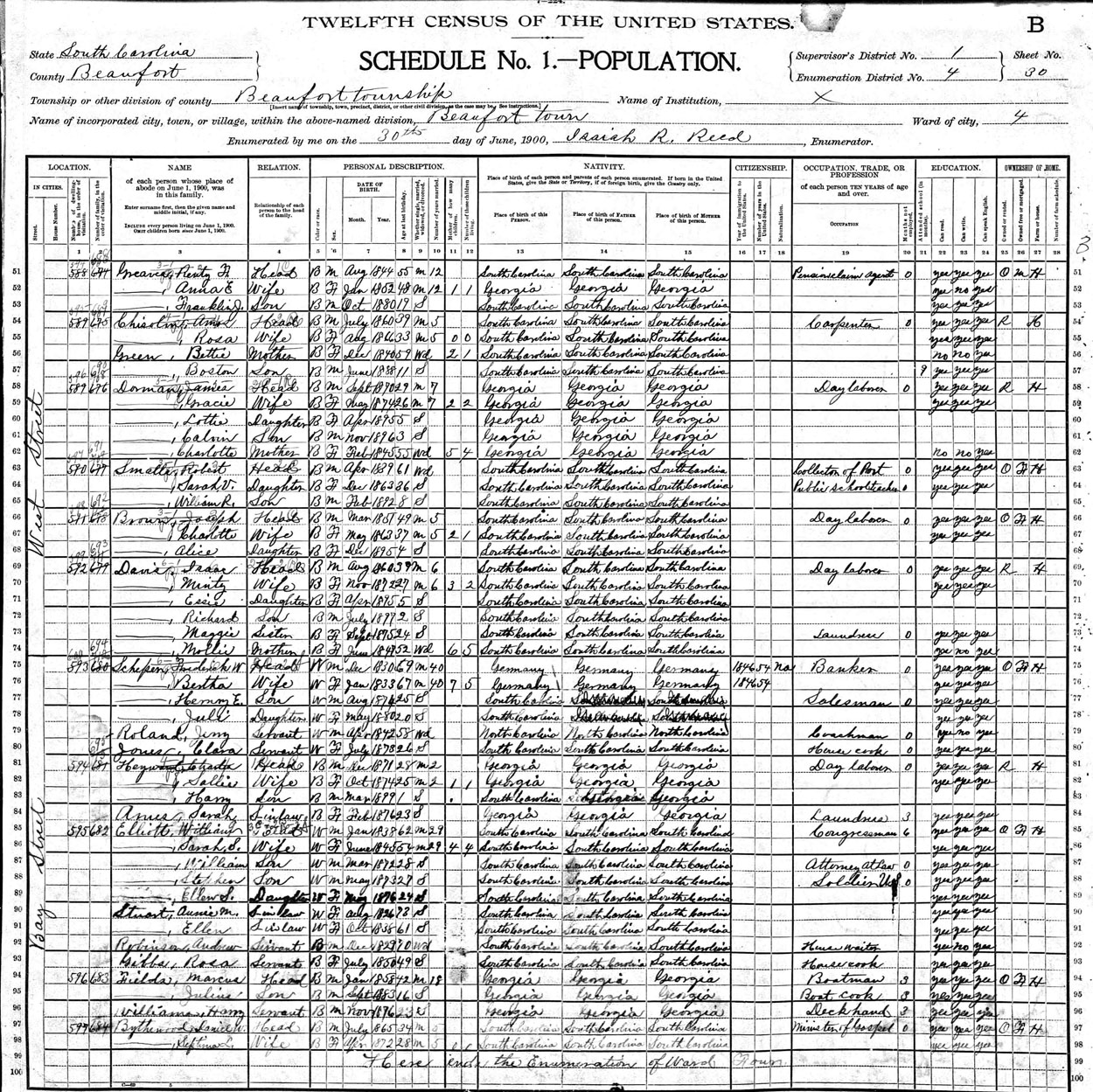

Eventually, he was able to buy and sell real estate—he owned a farm, entered into partnership with Robert Smalls, bought and sold a house, and identified Julius I. Washington as his attorney. The 1900 census finds him living on West Street in Beaufort, a few houses away from Smalls.

Hilton Head and Beaufort were ideal settings for those who were particularly industrious and highly motivated to take advantage of the market for goods and services. Greaves is listed on the 1866 IRS tax assessment as a "dealer" who was assessed $10.00. After moving to Beaufort, he also operated a store (confectionary and notions). In 1874, Greaves, Robert Smalls, and roughly 15 others were granted incorporation by the South Carolina General Assembly as the "Beaufort County Agricultural and Mechanical Association." The purpose of the group was to promote agricultural and mechanical arts and other industry and ingenuity through an annual fair to be held in Beaufort County.

Greaves married his first wife, Sylvia, on October 30, 1864, while living on Hilton Head Island. When he opened an account in the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company in Beaufort on February 27, 1869, he reported that he and Sylvia were separated for a period of time. This was not a permanent situation, as census records for 1880 show Renty and Sylvia as parents of two young sons, Joseph and Franklin. Both sons died as young adults; they were unmarried and had no known children. When Sylvia died in 1888, Greaves married a widow, Anne Elizabeth Smith (born in Georgia), about two to four months later.

Greaves was no stranger to the court system. His encounters with the law were numerous and varied, spawning newspaper commentaries and editorials on the character of elected officials, a common complaint during the period. In later years, Greaves managed to avoid a conviction for taking an illegal fee as a pension agent by entering a plea of no contest.

Despite his brushes with the law, Greaves was elected to two local public offices in Beaufort County: county commissioner and county coroner. He also held two federal patronage jobs: assistant lighthouse keeper and pension agent. Over the course of his careers as political and civil servant, he faced public criticism for acts of omission or commission.

Holding Public Office

As county commissioner of Beaufort County, Greaves was part of a three-member board with comprehensive power over roads, highways and ferries, and taxes. Commissioners served two-year terms. He was in a position to make a tremendous impact on county government. The county commission had taxing and spending powers to meet the local concerns of the county. He appeared on the ballot with Robert J. Martin and Vincent S. Scott for county commissioner in 1877, but his career seems to have been short-lived. He and fellow Republicans from Beaufort County were fighting threats against their lives and their freedom. Challenges faced in local politics are documented in the writings of Laura M. Towne, a resident of the Sea Islands. In 1878, Towne reported in her diary entry for November 6:

Renty Greaves, chairman, and the other county commissioners were all arrested for not keeping the roads and bridges on St. Helena in order, and were held on $5000 bond for Renty, and $1000 for the others, including even the clerk—our school commissioner. . . . Besides this, they arrested them late on Saturday night so that they should have to spend Sunday in jail. But they found bondsmen. . . . Then the Judge bulldozed Renty Greaves—told him he would have a term in jail, but that if he would resign his chairmanship to Dr. White . . . he should be set at liberty at once, and his bondsmen released. Renty, by virtue of his office, was one of the Board of Jury Commissioners, and the only Republican on it. If he resigned to Dr. White, all would be Democrats and the juries chosen by them. He was scared into doing it, and so we have three Democrats in that office, where the whole county is Republican!

By 1881, Greaves and his family had left Hilton Head Island and moved to Beaufort. While there, he was elected as coroner for Beaufort County on the Fusion ticket, a mixed ticket of blacks and whites. The Fusion movement was controversial because it was a system under which white Democrats and black politicians agreed to share power and elected offices in majority black districts.

Under the Fusion arrangement, the name of the nominee for the position of coroner was to be designated by the Republican Party. Greaves was elected to serve as coroner, a position with a four-year term. As county coroner, his job was mostly administrative in nature; he was responsible for investigating deaths, determining the cause of death, and ordering autopsies when deemed appropriate (where circumstances may have been suspicious or unusual).

The coroner was also empowered by law to appoint a deputy or deputies as needed, with approval of the county commissioner. He could serve in the capacity of sheriff if the sheriff was unable to perform his duties. Greaves's term as county coroner appears to have been relatively uneventful, despite a rocky start. The election outcome was the source of public controversy and litigation. As a local politician, he experienced, witnessed, or had knowledge of the violence, intimidation, and fraud that were rampant. His name appears frequently in transcripts of testimony given about events and circumstances in contested elections in Beaufort County.

It was not unusual for many black officials, after the end of Reconstruction, to survive on federal patronage jobs. Greaves was no exception, working as an assistant lighthouse keeper for the U.S. Lighthouse Board in the U.S. Treasury Department and later as a pension agent for the U.S. Department of the Interior.

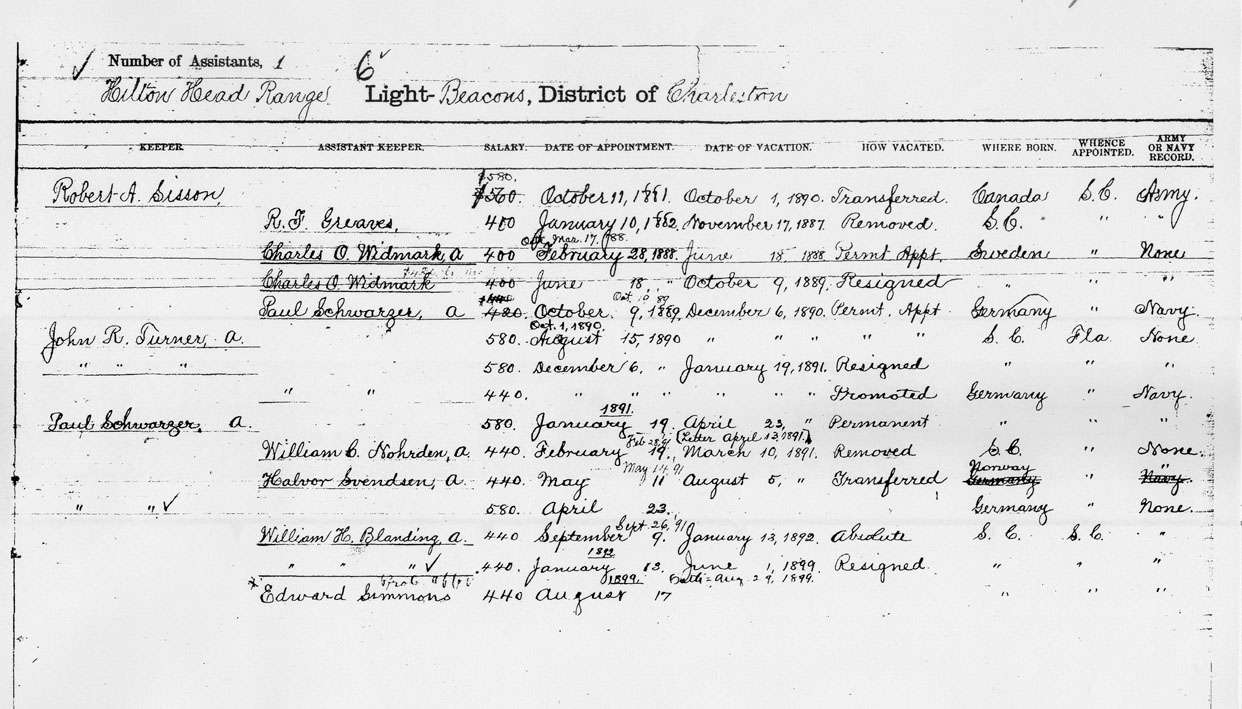

Greaves was an assistant lighthouse keeper on what was Leamington Plantation on Hilton Head Island from January 10, 1882, to November 17, 1887, earning an annual salary of $400. Robert Smalls likely helped him get this appointment as Smalls was involved with securing funds from the secretary of the Navy to provide for range lights for the Port Royal harbor. He may also have received assistance from Julius Washington, the Greaves family lawyer, who held various positions with the Customs House during this period. Lighthouse keepers were usually nominated by the customs collector.

According to records of the U.S. Lighthouse Service, Greaves was responsible for the front range light while the head lighthouse keeper and his son were responsible for the rear range lights. Correspondence indicates that there was a constant rift between the head keeper and his assistant, Greaves. The head keeper insisted that he did not need an assistant; he was convinced that his son was adequate for the task. Greaves fired back with his own accusations and explanations of events. He accused the keeper of being negligent by having a mere boy perform vital and dangerous work that required mature judgment.

Greaves's personnel file also contains letters from a creditor, W. D. Brown, owner of a local store. Brown reported negative information about Greaves that appeared in the local paper and complained about him for not honoring his debts. Greaves responded to the accusations with counterclaims against his supervisor and defended himself against attacks by Brown. He painted a picture of himself as the victim of unfounded claims and asked the Lighthouse Service to disregard them. He also questioned the storekeeper's business sense and possible motives for continuing to extend credit to him if he was such a poor credit risk. Greaves was removed from the position in 1887, but he continued corresponding with the National Lighthouse Service, challenging his removal, until 1888.

Greaves's second patronage job was as a pension agent/pension attorney for the Department of the Interior. Disbursement of pensions for Union veterans of the Civil War has been described as a cash bonanza for the Republican Party. The party was often accused of running a corrupt Pension Bureau by offering to expedite claims for potential Republican voters.

As a pension agent, Greaves assisted veterans, their widows, and dependents in completing applications for pension benefits for a fee. He says he became a recognized pension attorney about 1889; eight years later he was arrested for taking an illegal fee. The case against Greaves was dropped by the prosecutor, and Greaves's clerk, Ben Simmons, was convicted and sent to the penitentiary.

Greaves was eventually disbarred as an attorney or agent for the Department of Interior on January 30, 1903. The specific reasons for his dismissal have not been determined. Although charges against Greaves were dropped, the negative publicity surrounding the accusations is another example of the personal and professional attacks upon black officials by Reconstruction's opponents.

The Final Years: Veteran, Pensioner

After helping others make successful pension applications, Greaves made repeated attempts to get a veteran's disability pension for himself, only to have his applications rejected. The reason the claim examiners gave was that his claimed physical disability was preexisting. Dissatisfied with the lack of progress from his own pension attorney, Greaves fired Nathan Bickford of Washington, D.C., and began to represent himself. Changes in the laws made it possible for Greaves to receive benefits for which he had been ineligible on previous applications. He was approved for an invalid pension beginning July 5, 1890, for $12 a month. His second wife, Elizabeth, received widow's benefits of $8 a month.

In 1903, the year Greaves died, Beaufort County was reported to have 3,434 literate black males to 927 whites. The respect shown Renty Greaves in death sharply contrasts with the accusations, insults, assaults, and criticisms heaped on him in life. His obituary in the Beaufort newspapers described him as "an esteemed colored citizen," and he was buried in Beaufort National Cemetery.

Greaves and the Legacy of Beaufort County

By 1876, the South was in the early stages of a counterrevolution. However, blacks in Beaufort County continued to be a political force because they continued to send representatives to the state legislature and elect local city and county officials. In 1895, though, a state constitutional convention virtually nullified the 15th amendment for blacks in the state through the requirements for voting. Still the strongest black district in the state, five of the six blacks at the convention were from Beaufort County.

While it was probably not the future the freedmen had envisioned after a promising beginning, blacks in this region still fared better than most in the state and in the South. Many still owned their land and could support themselves. For a short period time they exercised control over matters such as public expenditures, poor relief, the administration of justice, and taxation policy, thus having an impact on the day-to-day lives of all Southerners, black and white.

The legacy of men like Renty Franklin Greaves is that they persevered despite disappointment and persistent, vicious attacks from their adversaries. They refused to be discouraged when faced with unimaginable odds.

Giselle White-Perry teaches criminal justice and criminology at South Carolina State University in Orangeburg, South Carolina. She enjoys researching the history and genealogy of families living in the Sea Islands of South Carolina.

Note on Sources

This article was originally presented as a paper at the annual meeting of the Southern Conference on African American Studies, Inc., in Charlotte, NC, February 12–14, 2009, under the theme "Heroic Acts, Heroines, and Heroes Throughout the Diaspora."

Primary sources from the National Archives were found in Greaves's Civil War pension file, Case of R. F. Greaves alias Renty Cruel, No. 823054, and the pension file for his widow, Elizabeth Greaves (Records of the Veterans Administration, RG 15); the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company records (Records of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, RG 101); and the 1880 and 1900 federal census and the 1890 veterans census (Records of the Bureau of the Census, RG 29). Accounts of his employment history in patronage positions were found in Records of the U.S. Coast Guard (RG 26) and Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior (RG 48).

Records of the Drayton Family in the South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston, SC, chronicle Greaves's claims for improvements on property owned in Mitchelville.

Challenges Greaves faced in his early political life are recorded in Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne Written from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, ed. Rupert S. Holland (New York: Negro Universities Press, 1912). Eric Foner's Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, rev. ed. 1996) identifies the significance of black leaders of this era to American political history. In A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press–Belknap Press, 2003), Steven Hahn explains how black leaders were able to mobilize and make the transition from slavery to self governance in such a short time.

Biographies of Robert Smalls were useful in identifying the local, state, and national officials with whom Greaves was acquainted—especially Okon Uya's From Slavery to Public Service: Robert Smalls 1839–1915 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971) and Edward Miller's Gullah Statesman: Roberts Smalls from Slavery to Congress (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1995). Examples of joint ventures by Smalls and Greaves were found in "An Act to Incorporate the Beaufort County Agricultural and Mechanical Association, approved February 12, 1874," Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of South Carolina passed at the Special Session of 1873 and Regular Session of 1873—74 (Columbia, SC: Republican Printing Company, State Printer, 1874), and "Beaufort District Grantee (Seller) Index 1864 to 1980," Conveyance Books, Index to Deeds.

Articles from local newspapers, the Palmetto Post and Beaufort Gazette, found at the Beaufort County Library, reported a number of events in Greaves's life: his election as coroner, his arrest and that of his father, the death of his youngest son, and his own death.

Insights into life after Reconstruction were found in George Tindall's South Carolina Negroes, 1877–1900 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1952), and Edward Ayers's The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).