A Soldier of the Revolution

Or, Will the Real Isaac Rice Please Stand Up.

Fall 2010, Vol. 42, No. 3

By Thomas A. Chambers

© 2010 by Thomas A. Chambers

"He [is] intending . . . during the summer, to sell cakes, beer, and fruit to visitors."

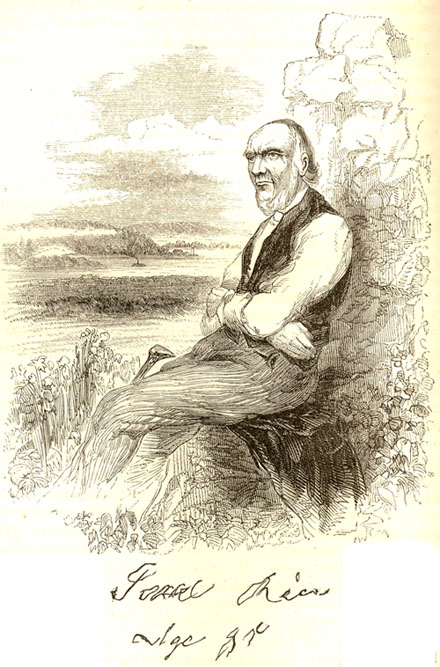

Such was the fate of Revolutionary War veteran Isaac Rice amid the ruins of Fort Ticonderoga. By July 1848 he and other aged soldiers—Rice was probably 83 when illustrator and guidebook author Benson Lossing met him—eked out a marginal existence by telling tales for tips, reminding tourists that he was forced to "depend upon the cold friendship of the world for sustenance, and to feel the practical ingratitude of a people reveling in the enjoyment which his privations in early manhood contributed to secure."

Rice's 1850 appearance in Lossing's handsome, expensive Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution marked him as a living monument of the Revolution and a symbol in the nation's ongoing debate over how to treat its veterans.

But who was Isaac Rice?

Was he an actual veteran who fought in the Revolution, a fictional character embellished by Lossing to appeal to the public's preconceptions of "suffering soldiers," or a 19th-century version of identity theft, where an elderly man adopted the persona of a long-dead veteran to gather a few coppers from tourists predisposed to honor the Revolution's memory?

Rice's identity remains uncertain; his representation of mid-19th-century ideals of the Revolution is clear. He was a living reminder of the romanticized past most Americans preferred.

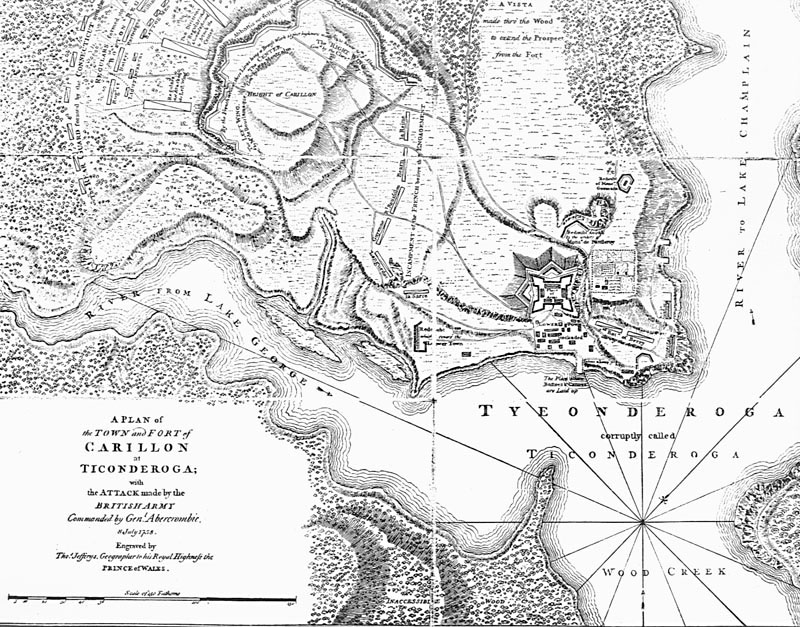

Historical Tourism at Fort Ticonderoga

I first met Isaac Rice in the summer of 1991, when as a brand-new college graduate I put my history major to work as a historic interpreter at Fort Ticonderoga, a restored 18th-century fortress and battlefield on the shores of Lake Champlain along the New York–Vermont border. Part of our unofficial orientation as tour guides was to visit the grave of Isaac Rice, located a few hundred yards outside the fort's walls. No visitors marred our after-hours reverence for the man we dubbed "the patron saint of tour guides" and a model for extracting tips from the patriotic public. We raised our beer bottles in his honor, hoping that the ghost of Isaac Rice would whisper in our ears as we guided sunburned vacationers about the old fort's grounds. I never heard Rice's voice or saw his specter walking the fort walls, but I felt a kindred spirit with him.

About a decade after leaving Ticonderoga, I met Isaac Rice again. There, gazing at me from an engraving in Lossing's book, was my old friend. Looking for a new research topic, I decided to pursue the man who inspired me to get into this whole history racket in the first place. My initial task was to determine if tour guides like Isaac Rice might have ever existed at Fort Ticonderoga. One determined tourist in 1800 discovered two locked doors and "found some human bones in one of the cells." Although the driver and tour guide "knew a great deal," the young tourist "wish'd he knew more" and complained that the guide provided "very imperfect information." Tour guides existed and were part of the experience at Ticonderoga well before Benson Lossing met Isaac Rice, but they fell short of their visitors' expectations.

In 1835 Nathaniel Hawthorne toured the fort under "the scientific guidance of a young lieutenant of engineers, recently graduated from West Point." His tutorial in military history transformed Ticonderoga into a place "having a good deal to do with mathematics but nothing at all with poetry." Hawthorne would have preferred "a hoary veteran to totter by my side," who told stories of military gallantry and "mustered his dead chiefs and comrades" to march past them in a ghostly review.

Hawthorne imagined that "the old soldier and the old fortress would be emblems of each other." Just over a decade after Hawthorne's visit, such a figure inhabited Ticonderoga's ruins. The first record of a Revolutionary War veteran guiding visitors dates to 1849, when Cyrus Morton "Reconoitred the old fort grounds." Amid the walls stood "an old man that was a Soldier there in the Revolution." The veteran "told us all about it and we gave him a pittance for his courtesy as all visitors do." The next year a female visitor "wandered about some time with an old Revolutionary soldier" who lived near the ruins. After her guide recounted tales and pointed out where Ethan Allen entered the fort, she, too, tipped the aged veteran.

Could this figure have been Lossing's Isaac Rice? "Kind and intelligent," Rice guided Lossing's party about the ruins in July 1848, answering questions and identifying features. The white-haired octogenarian Rice obtained "a precarious support for himself from the free will offerings of visitors to the ruins of the fortress where he was garrisoned when it stood in the pride of its strength." A technicality had deprived Rice of his due pension, and the members of his immediate family had died, but he remained optimistic. He had "'heard that the old man who lived here, to show visitors about, was dead, and so I came down to take his place and die also.'" Rice hoped to clear away the brush from a small room, "arrange a sleeping place in the rear, erect a rude counter in front, and there, during the summer," sell refreshments.

The man mentioned by visitors between 1848 and 1850 died just two years later, on August 11, 1852. "In accordance with his dying request, he was interred in the old Soldier's burying ground adjoining the fort." The details of the obituarymdash;Rice's "tall gaunt form" and "aged 87 years"—resemble Lossing's description. And like the veteran referred to by tourists in 1849 and 1850, this Rice "has, for several past years, acted as 'Cicerone' or guide, in pointing out the various interesting parts of the old French Fort Carillon, so famous in Revolutionary and ante-Revolutionary history." His gravestone called him simply "A Soldier of the Revolution." Clearly, someone calling himself Isaac Rice existed at Ticonderoga around the time of Lossing's visit. But who was he? When and where was he born? Did he serve in the Revolution? And was he the impoverished veteran he claimed to be? It was in setting out to learn more about Isaac Rice that I finally encountered his ghost.

Which Isaac Rice?

The most obvious biographical source was military records, in particular Revolutionary War pension files, that might verify Rice's claim that "in consequence of some lack of documents or some technical error, he lost his legal title to a pension." Only one Isaac Rice appears on the list of suspended pensioners from the 1832, 1836, and 1838 laws compiled in February 1852. That Lossing's Isaac Rice was still alive at that date, and that he claimed to be a widower, narrowed my search. Broader research in Revolutionary War pension applications turned up 91 applicants with the surname Rice, including three Isaacs. The most promising pensioner lived in Windsor County, Vermont, and had served as a private in the Massachusetts Continental line. This Isaac Rice first appeared on the pension rolls in 1818. His application claims that he served in Col. Thomas Nixon's Sixth Massachusetts Regiment between May 1777 and May 1780 and "was in the battle at Stillwater, New York—also at Saratoga." These tidbits of his military service appear to match Lossing's report that Rice "performed garrison duty at Ticonderoga under St. Clair," when he was "a drummer boy in the garrison that escaped," and later that year "was in the field at Saratoga in 1777, and served a regular term in the army." Service records confirm that Isaac Rice served in the Sixth Massachusetts, a unit present at Saratoga. As tantalizing as the connection might seem, this is not Benson Lossing's Isaac Rice. Pensioner Number S. 41,096 from Windsor, Vermont, was 62 years old in 1818 and had "died September 25, 1824," disqualifying him from meeting Lossing over two decades later.

Rice's birth date is far from clear. If he was 87 years old as his 1852 obituary indicates, he was born in 1765. Lossing lists him as 85 years old in two different publications; he based both accounts on his late July–early August 1848 visit. Rice told Lossing that he had not participated in Ethan Allen's 1775 capture of Ticonderoga but had been there in 1777, "then a lusty lad nearly thirteen years old." If we take Rice at his word, he was born in 1764. According to his obituary, Rice would have been 84, not 85, in 1848; either the biographer or the newspaper was wrong. Perhaps a one-year discrepancy is negligible.

This 1764–1765 birth date also rules out the second pensioner found on rolls, John Rice, who "when young was called Isaac Rice." He was 65 when he applied for a pension in 1818, therefore born in 1753. He also claimed to have fought in the battles of Trenton and Princeton but was not in the army during the Saratoga campaign and died in 1836. The third Isaac Rice, however, was born in 1762 in Wallingford, Connecticut. His military service started in 1778, after the fighting at Ticonderoga and Saratoga. Due to his limited service time with Connecticut troops, he only qualified for a pension under the June 7, 1832, law. He lived in Trumbull County, Ohio, and received a pension from 1833 to 1841. Phebe Rice collected the payment for her "dec'd" father until 1843. None of the Isaac Rices who applied for a pension is our man.

After Saratoga, Lossing's Rice claimed to have "enlisted as a private . . . and was stationed in Eastern Massachusetts" in 1778. Six men named Isaac Rice served in Massachusetts forces during the Revolution, but only one was active at this time. The only Isaac Rice who fought for New York enlisted in the Weissenfels regiment, formed in 1781. Connecticut's Isaac Rice also served too late, in 1780 and 1781. Vermont rolls list an Isaac Rice who engaged in four brief militia stints in 1780 and 1781, but not at Ticonderoga or Saratoga years earlier. Searches of rolls and service records indicate that only one Isaac Rice could have fought between 1777 and 1779—the man who served with the Sixth Massachusetts and later filed a pension in Windsor, Vermont. Yet he died a quarter century before Lossing would have met him. Military records alone fail to produce a definitive identity for Ticonderoga's 1852 Isaac Rice.

Census and Property Records

Perhaps census and property records could help to clarify the picture. Lossing recounted Rice's

tales of Ethan Allen's capture of Ticonderoga in 1775, but Rice had not been there. Instead, he had "heard my brother tell many things about the taking of the fort on that morning." The standard source on participants in Allen's attack lists only "Rice," but no first name or town. Isaac Rice bolsters his connection to the famous event, and to historical authenticity, by claiming "We lived near the old Catamount Tavern, in Vermont—did you ever hear of it? —where Ethan Allen lived a long time, and where the Green Mountain Boys mustered in the troublesome times before the Revolutionary War." The 1790 federal census for Vermont lists an Isaac Rice in Bennington, home to the Catamount Tavern, and he persists in the 1800, 1810, and 1820 censuses, at the correct approximate age.

But research at the Bennington Museum fails to confirm that any Isaac Rice living in Ethan Allen's base could be Lossing's Isaac Rice. That institution finds records for only three Isaac Rices in their collections. One born in 1742 likely appears on Vermont military rosters, in 1780 and 1781; the units listed mainly came from the Bennington area. He died in 1824 and is buried in Bennington, as is a second Isaac S. Rice, 1785–1873. His son, Isaac R. Rice, Jr., lived in Bennington from 1824 to 1894. None of these men was the right age to have been at Ticonderoga in 1777 as a teenager, and one was already dead in 1852. The eldest Isaac Rice appears in 1780s Bennington town records as a grand jury man, surveyor, and other civic roles, positions of some distinction that a propertied, respectable family man in his 40s might hold. Lossing's Isaac Rice was too young and poor to match any candidate who lived in the Bennington area.

In fact, other evidence in Lossing's Pictorial History points to a man who inhabited a different state during the Revolution. A footnote reads: "His father was a lieutenant in the English service, and belonged to the Connecticut troops that were with Amherst when he took Ticonderoga." Only one man meets part of these criteria. Asa Royce served as a second lieutenant in the Second Connecticut militia regiment in 1755 and as a first lieutenant in the same unit in 1756. No record confirms that Asa Royce, whose surname was interchangeable with "Rice" in 18th-century New England, fought in Jeffrey Amherst's 1759 capture of Ticonderoga. But the name confirms Isaac Rice's claim about his birth and age. Asa and Anna Rice's son Isaac was born on October 14, 1765, in New Hartford, Litchfield County, Connecticut. This date correlates with the 1852 obituary age of 87. The 1762 birth record of an older sibling refers to Asa as "Lieut.," corroborating Isaac Rice's claim of his father's rank.

This information connects this family to Lossing's Isaac Rice. His brother "was twenty years old on the day the fort was taken" in 1775 and "led a squad of men just behind Colonels Allen and Arnold." Born on September 1, 1754, to the same parents as Isaac, in the nearby town of Wallingford, Connecticut, Asa Rice, Jr., would have been 20 years old when Ethan Allen captured Ticonderoga, as his younger brother reported. The circumstantial evidence of Asa senior and junior led me to believe that the Isaac Rice that Benson Lossing met at Ticonderoga was one of the Wallingford Rices.

Truth or Fiction?

Isaac Rice existed, and his birthplace, birth date, and family seem verifiable. But a pattern of flexible truth emerges from Rice's account. He was three years younger than he claimed, and would have been nine years old when Allen captured Ticonderoga, too immature to enlist even by the lax standards of the 18th-century military. His father did serve in the colonial militia, and his regiment marched toward Lake Champlain during the French and Indian War. But the 1755 and 1756 campaigns were inglorious and could hardly be used to boost Rice's image of himself as a military hero.

Isaac claimed that his brother Asa "was one of the garrison" when Burgoyne captured Ticonderoga in July 1777. This is entirely possible, as Pvt. Asa Rice appears on a roll of Connecticut men captured by the British on May 19, 1776, in Canada. Released the next day, he could have returned to Ticonderoga and fought there the following summer. Asa Rice did serve three years in one of Connecticut's Continental Army units but enlisted in Baldwin's Regiment of Artificers in March 1778, well after the Ticonderoga evacuation during the Saratoga campaign. Baldwin's was present at Ticonderoga in June 1777, just before Gen. Arthur St. Clair evacuated the fortress. Returns do not list individual soldiers, so it is entirely possible that Asa Rice could have fled the British advance with St. Clair's forces. His younger brother, however, has an even less circumstantial claim to attendance. When asked by Lossing if he served at Ticonderoga as "a drummer boy . . . when Burgoyne took the fort," Isaac Rice claimed that he marched "in the escorting band, and stood not more than three rods from the generals." While the age and detailed description seem compelling, troop returns from Ticonderoga in June 1777 list no drummers among Baldwin's Artificers.

Rice went on to claim that he and his brother also fought at Hubbardton, Vermont, during the American army's retreat. Isaac described the British artillery position on Mount Defiance that prompted Gen. Arthur St. Clair's evacuation of Ticonderoga, the flotilla's progress up Lake Champlain, and even the land retreat into Vermont. "My brother was slightly wounded in his leg at Hubbardton, and a bullet took off one of my fingers, as you see, and made a little hole in my drumhead." Such detail, and especially a missing appendage, made for a compelling tale. But it is unclear if either Asa or Isaac Rice fought at Ticonderoga or Hubbardton. No Connecticut troops, and certainly not Baldwin's Artificers, are listed among the specific regiments at Hubbardton. If the Rices were there, they were likely stragglers separated from the regiment.

Again, military records fail to corroborate his tale. No Asa or Isaac Rice from Connecticut or Vermont appears on service records from the Saratoga campaign. While it is entirely possible that the Rices might have flocked to Saratoga along with thousands of New England militia in late September and early October, no evidence proves this potentiality. They might have been among the 71 men from Baldwin's Artificers, the only demonstrable unit connection for either Rice, at Saratoga, but Asa's enlistment date postdates the Saratoga campaign.

Isaac Rice's military service apparently continued after 1777. Probably still only 12 years old, Isaac Rice "enlisted as a private in a company of which my brother was captain, and was stationed in Eastern Massachusetts." They joined Col. John Sullivan's defense of Newport, Rhode Island, "and were in the battle on Quaker Hill" on August 29, 1778. Connecticut state troops did fight in that battle, so it is entirely possible that the Rices participated, especially considering that the date of Asa's enlistment in Baldwin's Regiment was a few months before the Newport campaign. But if Asa Rice was a captain, it was likely in a short-term militia unit raised for the campaign, not Baldwin's Artificers. The only Capt. Asa Rice listed in Revolutionary War records was in Church's New York Regiment, a state militia regiment from Cumberland County, the name New York State gave to the eastern side of Green Mountains along the lower Connecticut River, in what is now Vermont. Capt. Asa Rice signed a 1786 request for over £45 in overdue pay in Guilford, in eastern Vermont. This contradicts Isaac's claims to have lived near Bennington, part of Albany County on the opposite side of the Green Mountains, and his 24-year-old brother's rapid rise from private to captain seems unlikely, especially if his promotion was in two different regiments from two different states. Again, the details of Isaac Rice's Revolutionary War stories leave gaps in the historical record.

The facts that can be found do not echo Isaac Rice's recollections. A bit of memory loss or casting a more positive spin on past events is understandable from an octogenarian recounting tales from seven decades ago. Yet in Rice's case the deviations from the verifiable facts point toward a repeated self-fashioning of a patriot claiming a personal connection to key events, a 19th-century Forrest Gump sitting on Ticonderoga's crumbled walls, telling tales of his brushes with history. His brother's prosaic enlistment in Baldwin's Regiment of Artificers never made it into Isaac Rice's reminiscences, perhaps because it sounded less valorous than the Green Mountain Boys.

Rice also claims poverty in the tradition of the "suffering soldier" trope that pervaded early 19th-century American politics and culture. Local records only approximate Lossing's description of Rice as "a venerable, white-haired man, supported by a rude staff, and bearing the insignia of the 'Order of Poverty,' [who] came out from the ruins of the northern line of barracks." Rice cultivated his image and played his part well. Yet his father, Asa Rice, had been prominent enough in Wallingford, Connecticut, to serve as a lieutenant in the Seven Years' War. He also purchased and sold land parcels of as many as 70 acres in Wallingford, New Hartford, and Sharon between 1758 and 1783, some for as much as £120. Asa Royce, Sr., left his widow and eight children an estate valued at £132 including £60 in real estate upon his 1785 death. Part of his estate had already been distributed to three married daughters or sold to his eldest son, with the remainder going to Asa's widow, three remaining sons, and young daughter. None of the sons inherited enough land to establish an independent farmstead, and they sold off their shares for cash as they moved elsewhere. Isaac Rice, living in Connecticut in 1786, sold nine acres of land "set out to me in the distribution of my honored Father Mr. Asa Rice's estate" for the meager sum of £15. He, too, left Sharon and by 1790 lived near his brother Barnabas in Canaan, New York. By the fall of 1810, all of the siblings had quitclaimed their rights to their mother's dower share of the estate. Isaac Rice came from middling, but certainly not impoverished, means.

Most of the Rice siblings sold their rights to Benjamin Young, the husband of Mehitable Rice, the oldest surviving child of Asa and Anna. Primogeniture and entail were achieved through indirect means. Mehitable and Benjamin remained in Sharon on the family farm while all seven other children, like the offspring of so many other New England farmers, moved to New York, Vermont, Massachusetts, or Ohio to seek their fortunes. The farmland and estate could not support all of Asa's descendents. As Isaac Rice told Benson Lossing, "I have been for almost eighty years a toiler for bread for myself and my loved ones, yet I have never lacked for comforts." He does not appear in town or county property or public office records for his two New York residences: Canaan in Columbia County and Ticonderoga in Essex County. This absence may indicate that he lacked sufficient wealth to purchase land or sufficient status to serve as even a fence viewer. While Isaac Rice may have exaggerated his straightened means, he certainly was not rich.

Ultimately, it seems impossible to prove or disprove Isaac Rice's story. He came from a fairly normal New England family, and one with a military tradition. He may even have served during the Revolution, but the existing records provide no convincing evidence. According to the commissioner of the Bureau of Pensions in 1932, "a careful search of the records fails to show such a claim on file on account of the services of Isaac Rice or Royce, who died August 11, 1852 at Ticonderoga, aged eighty-seven years." So far as the federal government was concerned, Benson Lossing's Isaac Rice did not exist. We are left with conjecture about a man who knew something about the Revolution—probably from experiences related by his brother Asa—and lived near Ticonderoga.

Another older brother, Seth, lived within a day's ride of Ticonderoga in 1790. The 1800 federal census places Seth in Chittenden County, Vermont, near Lake Champlain, and an unpublished Rice family genealogy dates his death to 1832 in nearby Castleton, Rutland County, Vermont. Might Isaac Rice, down on his luck after living near his brother Barnabas along the New York–Massachusetts border, have moved closer to his Vermont sibling, Seth? It is plausible that the family followed other Connecticut families in seeking better economic opportunities on the northern frontier. Asa Rice, Sr., sold his last parcel in New Hartford, Connecticut, in 1769 and did not purchase new land until 1774, in nearby Sharon, Connecticut. Perhaps during this period the Rices moved to new lands in what would become southwestern Vermont, and Seth, 22 in 1774, remained there. Isaac Rice told Benson Lossing that he left the army in 1779 to assist his ailing father "and went back to Vermont to manage our little farm for my mother." Whether Anna Rice lived in Connecticut or Vermont is unclear, but the family likely had a presence in Vermont. Perhaps he picked up enough Ethan Allen lore while living in that state to tell tales from the Revolution. He might have been the Isaac Rice who served several days in the Vermont militia during 1780 and 1781, overhearing legends of Allen's exploits from veteran Green Mountain Boys. Or maybe he read one of the many editions of Allen's captivity narrative in circulation. An account of Allen's capture of Ticonderoga, invasion of Canada, and later imprisonment in England went through five editions by 1849, around the time of Lossing's interview with Rice at Ticonderoga. The Burlington, Vermont, printer of several editions likely distributed and sold the book throughout the state, making it possible for Rice to have owned or read the text. The last pre-Lossing trace of Isaac Rice is the 1830 census, which places him in Chittenden County, Vermont.

A Figure of Revolution and Romance

If the veracity of Isaac Rice's biography remains elusive, the power of his narrative resonated with 19th-century Americans. Ultimately, the memories of the Revolution that he evoked mattered more than the facts of his life. The rare existence and advanced age of Revolutionary War soldiers—a veteran who enlisted in 1780 at age 15 would have been 85 in 1850—created nostalgia for those who had experienced the nation's making. Isaac Rice looked the part, told detailed stories of the Revolution and Ticonderoga, and commanded just enough personal connection to the site and the army to warrant authority. Determining exactly who Isaac Rice was tests the holdings of the National Archives and other repositories. We can surmise that he was born in Connecticut in 1765 and moved around the northeast before dying at Ticonderoga in 1852, but we cannot prove that he actually served in the Revolutionary War. It mattered little that Isaac Rice's face lacked sufficient whiskers to justify a shave in 1775 or 1777, or that the military knowledge he related derived from the experience of others. Sometimes the image of the past is more comprehensible and useable than the reality.

He offered an opportunity to reanimate Ticonderoga's crumbling walls, and he served as a direct, living link to a nearly dead past. Lossing's popular and tremendously influential book revived interest in the Revolution, remembering the past, and visiting historic sites as well as boosted sales of his volumes. His musings on Ticonderoga's history were shaped by the old patriot, who came and sat beside me. . . . [H]e has no companions of the present, and the sight of the old walls kept sluggish memory awake to the recollections of light and love of other days. "I am alone in the world," he said, "poor and friendless; none for me to care for, and none to care for me. Father, mother, brothers, sisters, wife, and children have all passed away, and the busy world has forgotten me."

Sentimental history and the tragic image of the "suffering soldier" proved powerful cultural icons in early 19th-century America. But even such fascination with history lasted briefly. Rice and Lossing talked for "more than an hour with a relation of his own and his father's adventures." Eventually, "late in the evening," Lossing "bade him a final adieu. 'God bless you, my son,' he said, as he grasped my hand at parting. 'We may never meet here again, but I hope we may in heaven!'"

The afterlife might be the only place that Lossing or anyone else interested in the Revolutionary War would have met Isaac Rice. Even his gravestone, erected in the 1850s on the fort's grounds, had fallen into disrepair by 1875 and was not replaced until 1901. Likewise, Rice appears fleetingly in the historical record and seemed forgotten until Benson Lossing cleared back the weeds of time and propped up the aging veteran. Lossing understood American nostalgia for an idealized past and used it to sell books; Isaac Rice realized that his countrymen longed to encounter a living monument to their nation's founding and played the part of a "suffering soldier" to eke out a meager existence in his last years. Both men used the past, and 19th-century America's preference for a romanticized one, to their own ends. Lossing interviewed Rice on a "pleasant moonlight evening," an apt setting for a man whose connections to the past faded in the light of day. Encountering Isaac Rice's ghost may be as close to the real man and his actual history as we will ever get.

Thomas A. Chambers is associate professor of history and department chair at Niagara University in western New York. He is currently completing a book-length manuscript on Revolutionary War battlefields and commemoration. Whenever possible, he visits Isaac Rice's grave at Fort Ticonderoga.

Note on Sources

Benson Lossing wrote two similar accounts of Isaac Rice. The first appears in The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1859), I: 121–130; the second, with some additional information, was published in Hours with the Living Men and Women of the Revolution (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1889), pp. 71–82. The most important study of Lossing is Gregory M. Pfitzer, Picturing the Past: Illustrated Histories and the American Imagination, 1840–1900 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2003).

The Fort Ticonderoga Museum holds several important travel accounts in its Thompson-Pell Research Center. For tourism at the fort, see Lucinda A. Brockway, A Favorite Place of Resort for Strangers: The King's Garden at Fort Ticonderoga (Ticonderoga, New York: Fort Ticonderoga Museum, 2001). The best published travel guide of the era is Theodore Dwight, The Northern Traveller; Containing the Routes to Niagara, Quebec, and the Springs; with Useful Descriptions of the Principal Scenes, and Useful Hints to Strangers (New York: Wilder and Campbell, 1825). The quotation from the "determined tourist" comes from the July 20, 1800, entry in the journal of Abigail May, which is in the New York Historical Association in Cooperstown, New York. An important expression of romantic ruins can be found in Nathaniel Hawthorne, "Old Ticonderoga: A Picture of the Past" The Family Magazine I (May 1836): 414–415, reprinted from American Monthly Magazine I (February 1836): 138–142. Isaac Rice's obituary appears in The Semi-Weekly Eagle, Brattleboro, Vermont (August 23, 1852): 3; and the Essex County Republican, Keeseville, New York, August 1852. His surname was interchangeably spelled "Royce" in public records.

The richest records used in this article are the military records held by the National Archives (accessed via Footnote.com). Specifically, M804: Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Applications Files allows searches by state and surname. The 1932 search of Isaac Rice's pension file (S. 4087, p. 37) is mentioned in a letter from the commissioner of pensions to Senator Bingham in response to a constituent's request. For specific soldiers or regiments, M881, Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War, 1775–1785, is categorized by state. A similar database, M246: Revolutionary War R/olls, 1775–1783, supplements the service records and is searchable by state and regiment. All of these primary sources are keyword searchable and display the original manuscripts in a convenient "filmstrip" style. Another important source is Rejected or Suspended Applications for Revolutionary War Pensions (Washington, DC: n.p., 1852).

There are published lists of Revolutionary War soldiers from individual states, including: Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War (Boston: Wright and Porter, 1905); Henry P. Johnston, ed., The Record of the Connecticut Men in the Military and Naval Service During the War of the Revolution, 1775–1783 (Hartford, 1889); John E. Goodrich, ed., The State of Vermont: Rolls of Soldiers in the Revolutionary War, 1775 to 1783 (Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle, 1904); James A. Roberts, New York in the Revolution as Colony and State (Albany: Brandow, 1898). I also consulted Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society Vol. IX. Rolls of Connecticut Men in the French and Indian War, 1755–1762. Vol. I, 1755–1757 (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1903).

Genealogy records consulted include federal census records for 1790–1850, available through the National Archives, and miscellaneous records in Essex County and Columbia County, New York, where Isaac Rice lived. Nicholas Westbrook consulted Essex County records. Tyler Resch of the Bennington Museum searched for evidence that Rice lived there. The Town of Bennington Clerk's Office has posted many early records on its web site. Harlan R. Jessup consulted microfilmed land, church, vital and probate records for relevant towns at the Connecticut State Library. On Connecticut migration to Vermont, and particularly the economic status of the Green Mountain Boys, see Michael Bellesiles, Revolutionary Outlaws: Ethan Allen and the Struggle for Independence on the Early American Frontier (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993). Rice's remarks on selling nine acres of his father's land appear in the Sharon Land Records in the Connecticut State Library in Hartford.

For the broader context of Revolutionary War veterans, see John Resch, Suffering Soldiers: Revolutionary War Veterans, Moral Sentiment, and Political Culture in the Early Republic (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999); Gregory T. Knouff, The Soldiers' Revolution: Pennsylvanians in Arms and the Forging of Early American Identity (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004); and Robert A. Gross, The Minutemen and Their World (New York: Hill and Wang, 1976). Alfred F. Young has written two excellent studies of Revolutionary War veterans and memory, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999) and Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004).