At the Edge of the Precipice

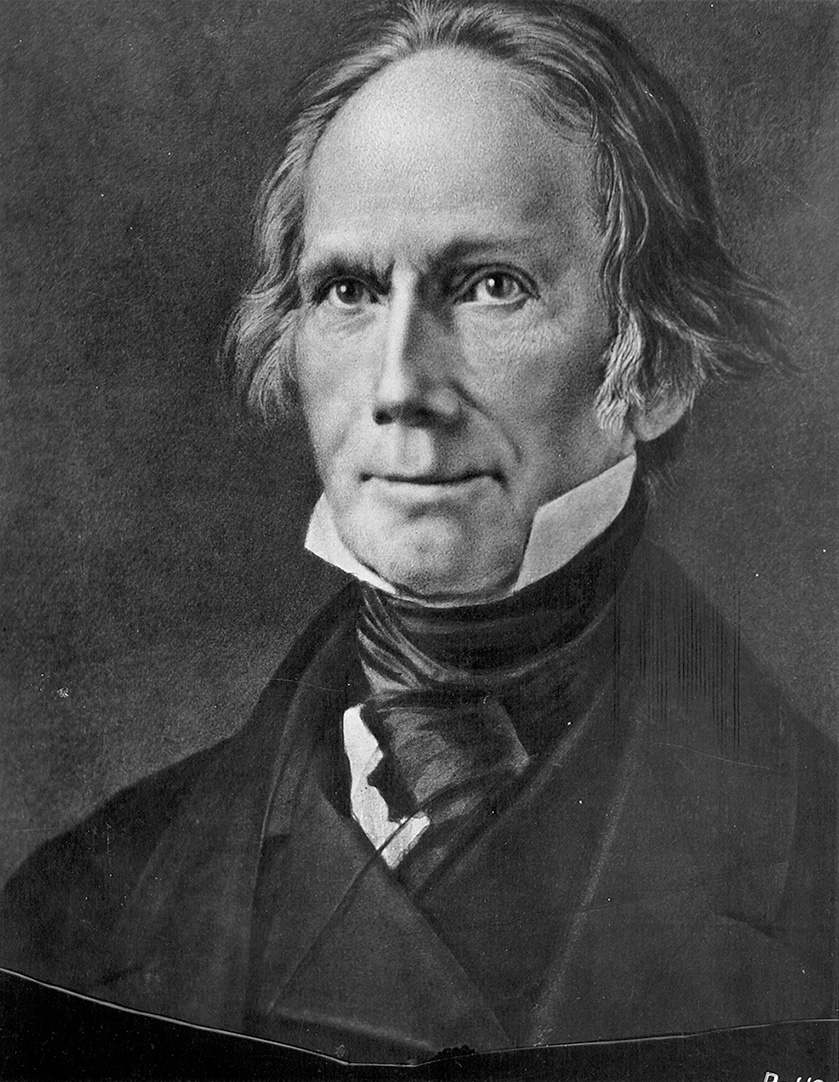

Henry Clay and the Compromise of 1850

Spring 2010, Vol. 42, No. 1

By Robert V. Remini

© 2010 by Robert V. Remini

In 1850, the Union of American states came close to being irreparably smashed. Several sets of demands from slave states and free states—many of which stood in direct opposition to one another—threatened to explode into secession. Only a compromise satisfactory to both sides could prevent catastrophe.

Had war resulted between the North and the South in 1850, rather than a decade later, it seems likely that the more militant South would have defeated the much weaker North and made good its separation from the Union. It is arguable that two or more independent nations would have been formed, thus permanently dissolving what was once the United States of America.

It would require an act of Congress to cool tempers and avoid a war. It would need to be legislation that contained something for both sides. And most especially, it would take an extraordinary legislator to forge bipartisan congressional support for what would become the Compromise of 1850.

The following is an excerpt from At The Edge of the Precipice: Henry Clay and the Compromise of 1850 by Robert V. Remini. Excerpted by arrangement with Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright ©2010.

Fortunately, there sat on the floor of the Senate a statesman who would find the means of concocting a solution, a political genius of the first rank. Though he was tired, aging, and fresh from a losing presidential nomination bid, the legendary Henry Clay was dedicated to preserving the Union and realized he must return to Congress to do what he could to keep the country whole.

As he headed south from New York and Philadelphia to Washington, Clay was startled to find at the Baltimore depot an enormous crowd who had been gathered, he said, “without preconcert or arrangement.” Here was a crowd in of all unlikely places, a railroad station. That was surprising. These people had come not only to salute him and show their affection and support but also to impress upon him their need and hope that he would use his considerable gifts to find a solution to the gathering crisis facing the country. When he tried to escape, they followed his carriage from the depot to his hotel in town, cheering him, waving to him, and calling his name. They did not relent when he entered the hotel. Not until he appeared at an open window on the second floor did they slowly quiet in the hope that he would speak to them. A few of them called out, “speak to us.” Clay shook his head. “We are too far apart, my friends, to do that,” he shouted to them. But he went on to say that he would meet with them the next day and shake each person by the hand.

And he kept his word. At 11 a.m. Clay positioned himself between two parlors on the first floor of the Barnum City Hotel and received the throng. First, he told them how delighted he was with the reception he had received and then he met each person individually. To a very large extent the crowd left the hotel feeling reassured that Clay would bring sanity and calmness to Washington and find the means to appease both North and South, thereby ending the crisis.

When Clay finally reached Washington he checked in at the National Hotel. Again crowds pursued him. Each day they came to his hotel, repeating the pleas he had heard throughout his trip. Benjamin Brown French, former clerk of the House of Representatives and a keen reporter of the Washington scene, marveled at what was happening. “It seems to me,” he wrote, “as if he [Clay] was ‘the observed of all observers’ instead of the President.” At the White House the Great Compromiser was surrounded as he passed through the East Room. “I could not but think,” French continued, “that, after all, he was the idol of the occasion. ‘Henry Clay’ is a political war cry that will at any time and in any part of this Union create more sensation among men of all parties than any other name that can be uttered. . . . He now stands, at the age of three score years & ten, the beau ideal of a patriot, a statesman, a great man!”

That phrase, “beau ideal,” was repeatedly used by others at the time. A young Representative from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, who had just completed his first term in Congress and did not seek reelection, said that Henry Clay was “my beau ideal of a statesman, the man for whom I fought all my humble life.”

But Clay’s arrival at Washington and the adulation accorded him everywhere aroused the jealousy and concern of the administration. President [Zachary] Taylor’s aides believed that Clay intended to assume control of the Whig party and act out the role of leader of the nation. And that belief did not bode well for any close relationship between the President and the Great Compromiser.

On Monday, December 3, 1849, Clay appeared in the Senate for the opening of the 31st Congress. It was quite a moment. His arrival created a sensation. Other Senators rushed to his side to greet him, and a thunderous ovation ricocheted around the chamber. He was really overcome by the emotion expressed on his return to Congress. “Much deference and consideration are shown me by even political opponents,” Clay commented with a sense of pride. “I shall by a course of calmness, moderation and dignity endeavor to preserve these kindly feelings.”

But as Clay took his seat he looked old and worn. He coughed a good deal, and his cheeks were shrunken. Still, his wide mouth was “wreathed in genial smiles,” just as in years past. He was back where he belonged, and not much had changed during his absence. At the age of nearly 73, he “generally kissed the prettiest girls wherever he went,” played cards in his room, and enjoyed a large glass of bourbon whenever he relaxed.

As he looked around the chamber, Clay recognized many old friends and enemies, men who played a major role during the Jacksonian years and still exercised considerable influence in national affairs. There were Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, Willie P. Mangum of North Carolina, Lewis Cass of Michigan, John Berrien of Georgia, and of course, the other two members of the Great Triumvirate, Daniel Webster and John C. Calhoun.

But there were also new members who, through their intelligence and leadership would shape national affairs for the remainder of the coming decade. These included Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, John Hale of New Hampshire, Jeremiah Clemens of Alabama, and William H. Seward of New York, among others.

The more he surveyed the scene, and contemplated the heavy burden of the expectations placed upon him, the more Henry Clay worried. “Upon the whole,” he told Mary S. Bayard, a Philadelphia friend, “there is a very uncomfortable state of things here both for the Whig party, and I fear for the Country. From both parties, or rather from individuals of both parties, strong expressions are made to me of hopes that I may be able to calm the raging elements. I wish I could, but fear I cannot, realize their hopes.”

Robert V. Remini is professor emeritus of history at the University of Illinois at Chicago and is cur-rently historian of the U.S. House of Representatives. He has written extensively about President Andrew Jackson and the Jacksonian era and has written biographies of Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams, Martin van Buren, and Daniel Webster. He won the National Book Award for the third volume of his study of Jackson.

Note on Sources

Henry Clay’s reception in Baltimore and his remarks to the crowd at his hotel are recorded in The Papers of Henry Clay: Candidate, Compromiser, Elder Statesman, January 1, 1844–June 29, 1852 (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1991), 10: 627–628. Clay’s reaction to his reception in the U.S. Senate appear in a letter to Thomas B. Stevenson, December 21, 1849, in the Papers, 10: 635. Clay’s letter to Mary Bayard is printed in the Papers, 10: 633.

Benjamin Brown French’s observations of Clay appear in French, Witness to the Young Republic (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1989), p. 213.

Abraham Lincoln’s comments on Clay are recorded in Edgar De Witt Jones, The Influence of Henry Clay on Abraham Lincoln (Lexington, Ky., 1952), p. 21.

The observations of Clay at age 73 are from Benjamin Perley Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis (Philadelphia: Hubbard Brothers, 1886), 1: 363.