68,937 and Counting

Searching Inmate Case Files from the U.S. Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas

Summer 2010, Vol. 42, No. 2 | Genealogy Notes

By Tim Rives and Steve Spence

A prison file is a two-edged sword. While it can offer unsurpassed biographical details on the life of its subject, it may also uncover more information than the sensitive genealogical researcher wants to know.

Not every family historian, for example, is interested in Uncle John's morphine habit or his love life behind bars. And the unkindest cut of all? It is a prison record, with all that implies. Genealogists may discover friends and relatives who once took great interest in their research suddenly avoiding them at social and family gatherings.

Uneasiness with the subject is justified, for the information cloaked in a prison file is a potentially dangerous weapon and must be handled carefully to avoid injuring others.

That's the warning. Here's the promise: those who use prison records in their genealogical research will be rewarded with information absolutely unavailable anywhere else on earth.

The National Archives at Kansas City holds 68,937 inmate case files from the United States Penitentiary—Leavenworth (Kansas). Contained in Record Group 129 (Records of the Bureau of Prisons) the files currently range in date from 1895 to 1952. Additional five-year blocks of records are scheduled to be accessioned every few years. Barring a radical change in human nature or the administration of justice, this record series will only continue to grow.

Since opening its doors in July 1895, Leavenworth has been home to some of the most famous and notorious federal prisoners in history. These prisoners include Robert Stroud, better known as the "Birdman of Alcatraz"; George "Machine Gun" Kelly; polar explorer Dr. Frederick Cook; labor leader "Big Bill" Haywood; boxing champion Jack Johnson; gambler Nicky Arnstein; and Native American activist Leonard Peltier. Lesser known are the tens of thousands of ordinary men (and about a dozen women) incarcerated for periods from a few months to a few decades.

What can an inmate case file tell us about any of them, the famous, the infamous, the unsung, or your black sheep ancestor? The inmate case file is democratic in form. The documents in the file of the "Birdman of Alcatraz" will be largely the same type as those found in the file of John Doe. (This includes all three "John Does," men too stubborn or embarrassed to give Leavenworth officials their true names.) Although there are many minor variations in case file contents, the "typical" inmate case file generally includes the following documents: inmate photograph, record sheet, personal data sheet, fingerprints, individual daily work record, hospital record, physician's examination of prisoner, correspondence log, personal correspondence, trusty prisoner's agreement, and sentence of court.

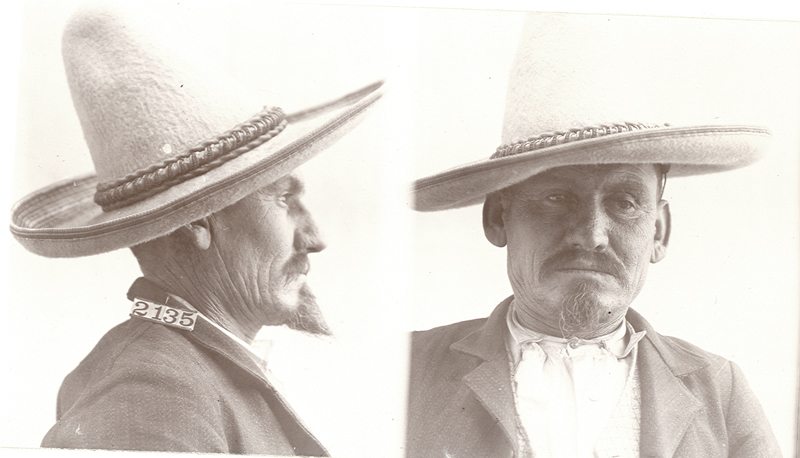

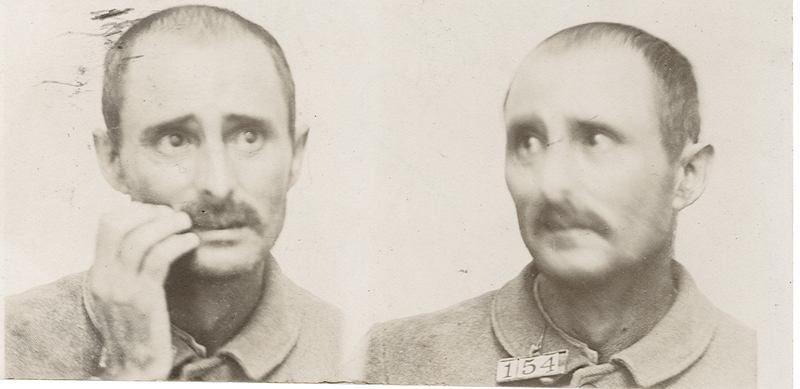

Inmate Photograph

Also referred to as the mug shot, the inmate photograph captured front and side views. In photographs from the early years, most subjects are wearing hats, as was the custom of the day. The record clerk was forced to re-shoot inmate George Rives, who ruined his "hat negative on account of acting crazy."

Record Sheet

This document includes the inmate's name, alias, inmate registration number, color or race, crime, sentence, fine, date received, court received from, date of sentence, date sentence began, maximum term date, minimum term date, good time allowed, occupation, age, date of parole eligibility, and the discharge date. Inmate occupations varied considerably.

Like death, prison is no respecter of persons. Leavenworth has been home to bankers, doctors, lawyers, con men, spies, actors, writers, scientists, train robbers, Indian chiefs, politicians, newspaper editors, Ku Klux Klan leaders, soldiers, jockeys, boxers, racecar drivers, and cowboys. More than 60 inmates gave their occupation as "ballplayer." Inmates Bill Wilson and Eul Eubanks played in the major leagues. Inmates Omer Newsome and Lemuel Hawkins once starred in the Negro Leagues.

The record sheet also describes an inmate's disciplinary violations. These violations range from the petty (say, talking in the chow line) to the serious (say, killing your cellmate). Most records sheets are full of charges like "smoking in cell" or "loafing and shirking," relatively mild infractions but of momentous meaning in terms of prison discipline.

Prisons control an inmate by placing a barrier between the prisoner and his freedom of action. The right to make choices is an important part of what defines us as free individuals. Take away someone's freedom of choice or action, and you in effect take away their autonomous self. In exchange for good behavior, prison officials return parts of the self to the prisoner in increments, usually in the form of petty privileges and choices of recreation: smoking cigarettes, watching movies, reading books, talking with co-workers, and the like. Prisoners who take these privileges unearned threaten prison order because they are asserting their autonomy like free men. Prisons cannot tolerate this. And that is why you will see page after page of seemingly petty disciplinary violations.

Personal Data Sheet

This document provides additional information on the inmate’s family background and criminal conviction. It records civil or military status; the name of the committing judge; the name of the district attorney; place of arrest; length of pretrial jail time; plea; nativity; date of birth; parental information; marital status; number of children; wife's address; permanent address; next-of-kin notification; education; literacy; religion; tobacco, alcohol, and drug use; age when leaving home; and miscellaneous remarks. Ray Perry, also known as Willis Armstrong, did not admit his drug addiction on his personal data sheet but confessed it in his prison memoir, Philosophy of the Dusk, seven years after he left Leavenworth. Perry/Armstrong used the nom de plume "Kain O'Dare."

Fingerprints

The fingerprint card captures basic physically identifying features such as fingerprints, height and weight, hair and eye color, marks, scars, moles, and tattoos. One tattoo, its deeper meaning now lost to time, is described as a "man riding a hog inside of a pentagram." Older files include "Bertillon" measurements with the fingerprints. Alphonse Bertillon was a French police officer who designed a pre-fingerprint physical identification system using measurements ("anthropometrics"), such as the length and width of the head and the degree of forehead slope. A set of identical twin inmates known as the "two Will Wests" exposed the weakness of the Bertillon system at Leavenworth when it declared them to be the same man.

Individual Daily Work Record

This record allows the researcher to discover what an inmate did every day of his or her confinement. It is difficult to imagine another record as comprehensive as a prison work record. There were up to 50 different jobs inmates could be assigned to at Leavenworth. These included work on the crusher gang, at the machine shop, and in the mail department. Some of the more unusual assignments listed on the sheet were the broom shop and band. Jack Johnson served as an orderly during his incarceration. Inmates worked every day of the week except Sunday.

Hospital Record

Not every genealogist will want to know the facts documented in an inmate's medical records. Venereal diseases and alcohol and drug addictions are noted here. Although it is popularly believed that bootleggers caused prison overcrowding in the 1920s, it was actually the large number of drug or "dope" offenders that filled the federal corrections system beyond its capacity. In 1925, for example, narcotics offenders outnumbered alcohol offenders by 10 to 1. Leavenworth had so many drug violators that they formed their own baseball teams. The "Morphines" and the "Cocaines" squared off in an annual contest to determine the best baseball-playing dope violators in the institution.

With all these patients, Leavenworth doctors had no choice but to pioneer the treatment of narcotics addicts. They injected prisoners with the alkaloid hyoscine to take the edge off withdrawal pains. This was fine for opiate addicts, but a little rough on cocaine users, who suffer no physical withdrawal. A powerful drug, hyoscine was used by Soviet intelligence agents as a truth serum.

Physician's Examination of Prisoner

This is a single sheet that lists basic physical information on a prisoner at the time of his arrival. The exam noted the height and weight of each prisoner and whether they used tobacco, liquor, or drugs. The prison physician examined each inmate for evidence of previous or present diseases and checked to see if the prisoner had a hereditary risk for tuberculosis, insanity, cancer, or epilepsy.

Correspondence Log

This document recorded the prisoner's incoming and outgoing letters. It reveals kin, work, legal, and friendship networks. It tells us, for instance, that Industrial Worker of the World radical Ralph Chaplin used the offices and influence of his Republican politician cousin to win his freedom. Blood is thicker than water and politics.

Personal Correspondence

This was considered a prisoner's private property if he followed institutional rules, a big IF in the prison world. Inmate Theodore Handy discovered the limits of this policy when he developed a crush on a Woman's Christian Temperance Union volunteer. She intended to inspire Handy to sobriety by sending him the antialcohol tract The Life of John Gough. She instead inspired his heart and pen to flights of romantic fancy. "If the man in insane," she complained to the prison's chaplain, "such letters can be excused. If he is rational, they are an insult." Handy lost his pen pal and his letters.

Trusty Prisoner's Agreement

Overworked prison officials appointed "trustworthy" inmates to positions of petty authority and responsibility, leading work crews in the completion of institution maintenance jobs. Since some of the men worked outside the prison walls without supervision, they were required to sign a contract, or "trusty prisoner's agreement." The agreement is valuable to researchers because it asked the inmate to state his offense in his own words. It also required the inmate to list two character references, potentially valuable leads for further researching an individual's life.

Sentence of Court

More important for the clues it provides than its actual content, the sentence of the court tells the researcher where the prisoner's conviction occurred. The docket number can be used to find the court case, which will provide more information on the inmate's criminal history and open new research leads.

Leavenworth inmate case file contents vary according to the era in which they were created. Early inmate files, those created between 1895 and 1905, are thin with a few exceptions. They usually contain the photograph, record sheet, sentence of court, and correspondence log only. As the 20th century progressed and institutions grew larger and more bureaucratic, inmate files expanded accordingly. Files created in the mid-20th century can amount to hundreds of pages. Of particular interest in the later files is the social interview, which the Bureau of Prisons began conducting with prisoners who entered the system in the 1930s. The social interview appeared at a time of high confidence in the ability of sociology to account for the root causes of criminal behavior. Every possible environmental influence was duly noted and weighed in the social worker's evaluation of the subject. The social interview offers a wealth of personal information, some of which may be restricted.

Federal prison records less than 72 years old are exempt from the Freedom of Information Act under subsection (b)(6). To quote from National Archives guidelines, "this type of record might include medical information, personal financial data, Social Security numbers, intimate details of an individual's personal or family life, or similar data."

In practical research terms, this means researchers can still obtain significant portions of case files that are less than 72 years old if the inmate was born more than 100 years go or if he is deceased and a copy of the death certificate is provided with the request. The medical, financial, or intimate personal information of other individuals—particularly children—will be deleted from copies made of records less than 72 years old. That said, other persons appearing in the file are entitled to information about themselves and may obtain relevant portions of those records.

Although this article has relied on the masculine pronoun, there were a few women sentenced to Leavenworth. But it is misleading to label them Leavenworth inmates since they averaged only two days of confinement at the federal facility before being moved a few miles south to the Kansas State Penitentiary at Lansing, Kansas. Unlike the federal penitentiary, the state prison had a women's wing. (Since 1927 federal female inmates have been sent to Alderson ,West Virginia.) A dozen female inmate files still survive in Leavenworth holdings, including that of Becky Cook. She was sent to Leavenworth for having her toddler daughter slip her tiny arm through mailbox slots to remove things that did not belong to her.

Requests for the files of Cook and other inmates have made the Inmate Case File series the most popular records series in the holdings of the Central Plains Region. Kansas City archivists receive requests daily from historians, journalists, and genealogists looking to document the history of American justice, follow the career of a famous outlaw, or solve a family mystery. These researchers have found in inmate case files a fine blade for cutting through the thickets of the past to reveal facts both illuminating and disconcerting.

For information on Leavenworth inmates, or to order a copy of a case file, please write to the National Archives at Kansas City, 400 West Pershing Road, Kansas City, MO, 64108, or send e-mail to kansascity.archives@nara.gov.

Tim Rives is the deputy director of the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum in Abilene, Kansas. He earned his master of arts degree in American history from Emporia State University in 1995. He was with the National Archives at Kansas City from 1998 to 2008, where he specialized in prison records. He is the author of numerous Prologue articles.

Steve Spence is an archives specialist at the National Archives at Kansas City. He works extensively in the Leavenworth prison records and in 2007 was the curator of the Leavenworth Penitentiary photo exhibit "Mugged."