"I Am Still in the Land of the Living"

The Medical Case of Civil War Veteran Edson D. Bemis

Spring 2011, Vol. 44, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By Rebecca K. Sharp and Nancy L. Wing

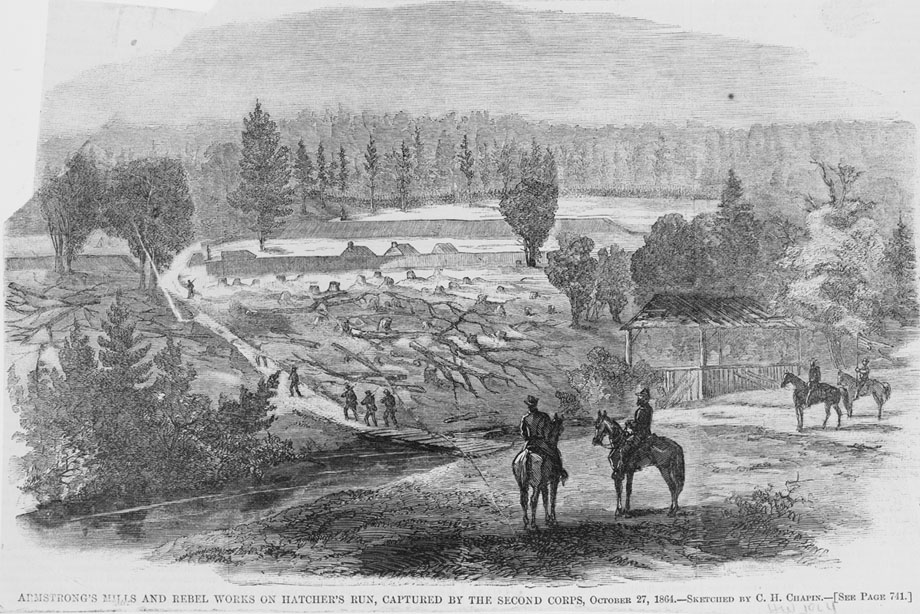

On February 5, 1865, Cpl. Edson D. Bemis of Company K, 12th Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry received a traumatic head wound from a conoidal musket ball during the Battle of Hatcher's Run, Virginia. Surgeon Albert Vanderveer reported on Bemis's condition upon his arrival at the field hospital:

[B]rain matter was oozing from the wound. There was a considerable hemorrhage, but not from any important vessel . . . the right side was paralyzed and there was total insensibility. [After Surgeon Vanderveer removed the musket ball on February 8,] [t]he patient's condition at once improved. He told the surgeon his name, and seemed conscious of all that was going on about him. . . . [During the next] ten days, [Bemis was limited to] answering direct questions, but indisposed to continue a conversation.1

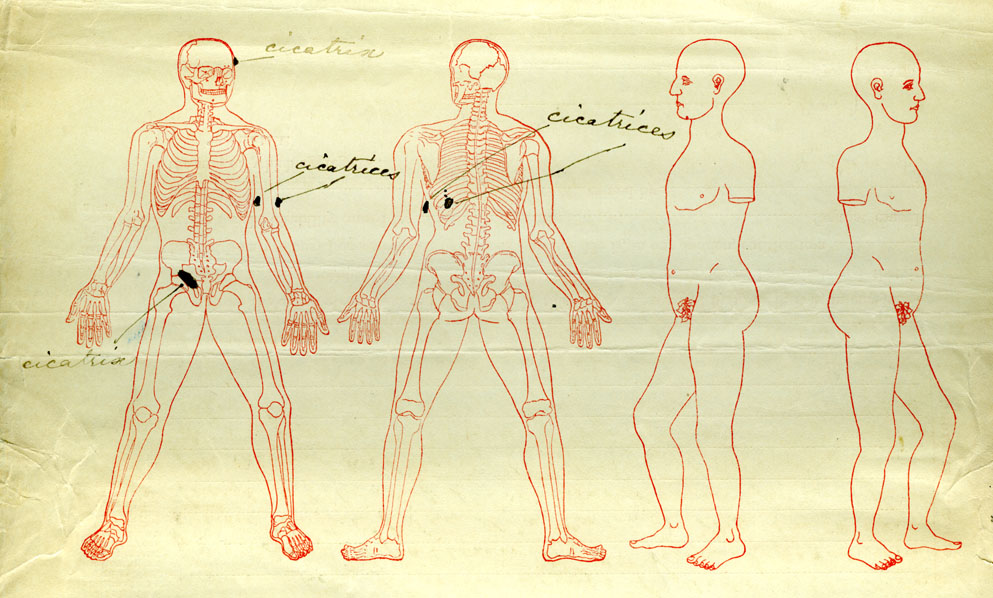

After his release from the hospital, Bemis continued to recover at his home in Massachusetts. Prior to the head wound, Bemis had sustained several other injuries. On July 13, 1865, he was discharged from the Army, and the Army Medical Museum photographed his nearly healed wounds.

The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion

This detailed case study is from the multivolume Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (MSHWR), published in the late 19th century. The MSHWR was begun by Union Surgeon General William Hammond, who wished to publish an extensive work on military medicine during the Civil War. The initial steps began in 1862 with the creation of the Army Medical Museum, today's National Museum of Health and Medicine. Museum staff obtained records, collected specimens, and photographed injured soldiers. Artists were hired to sketch wounds and specimens. The MSHWR was based on a variety of sources such as hospital registers, physician reports, captured and surrendered Confederate records, and Union and Confederate pension records.

Although the MSHWR focuses on Union medicine, it also includes information about Confederate medicine. This published work contains graphs, tables, maps, sketches, and copies of photographs. Topics include modes for transporting the wounded such as ambulances, hospital ships, and hospital trains; descriptions of unsanitary conditions within camps and hospitals; and treatments of diseases and injuries. Individuals are mentioned throughout. A large percentage of patients were soldiers, including prisoners of war and members of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). On occasion, nurses, local residents, African American contraband, servants, and patients treated in freedmen's hospitals appear in the MSHWR. Some soldiers are mentioned briefly, and others have detailed case studies. The volumes provide an overall sense of how medicine advanced during the war. Whether you are researching Civil War medicine or an ancestor who was ill or injured during military service, the MSHWR should be part of your research.

If the soldier survived the war, the MSHWR may include an update about the veteran's condition. The MSHWR contains this excerpt from Edson Bemis's 1870 letter to the editor of the surgical volumes: "I am still in the land of the living. My health is very good considering what I have passed through at Hatcher's Run. My head aches some of the time. I am married and have one child, a little girl born last Christmas. My memory is affected, and I cannot hear as well as before I was wounded."2 Although the MSHWR case study ends in 1870, records reveal more about Edson Bemis's life during and after his military service.

For your research to be as complete as possible, you should consult the MSHWR as well as records held by the National Archives and Records Administration and the National Museum of Health and Medicine. Although pensions may refer to a MSHWR case study, you should still check the MSHWR index in the absence of such a reference. For volunteer Union service, NARA holds a variety of records including compiled military service records, carded medical files, and pensions. These records may provide information about injuries, illnesses, hospitalizations, surgeries, and deaths. For Confederates, NARA has CMSRs and naval records. Because Confederate veterans filed for pensions in their state of residence, you should check with the appropriate state archives. If the MSHWR refers to specimens or photographs, the National Museum of Health and Medicine may have additional documentation.

Veteran Edson Bemis

Bemis's pension file consists of three envelopes that provide genealogical information as well as details about his struggles with physical and mental health until his death in 1900. Edson Bemis, the son of Joseph Bemis and Betsey Cole Bemis, was born in North Chester, Massachusetts. On January 6, 1869, he married Jennie A. Austin (some pension documents refer to her as Jane or Jane Amelia). The couple had three children: Jennie Eliza, born December 25, 1869; Edson Austin, born January 10, 1875; and May Bell Bemis, born April 23, 1877.3

Bemis's pension file contains numerous affidavits and letters that describe his deteriorating condition. Four years after operating on Bemis, Dr. Vanderveer wrote: I saw him again in Feb 1869 at Albany NY, when he appeared somewhat feeble, said he had had a few convulsions the previous summer and could not remain long in the hot sun or bear bending over much. The wound was well healed that pulsating brain could be noticed in standing some little distance from him.4

William L. Loomis, Bemis's former employer, verified that Bemis worked at his coal yard for 15 years and described his condition:

That during the time soldier worked for affiant he suffered at times from [the effects of the head wound] . . . , had pain in his head and dizziness and sometimes would be unable to perform his labor but having a wife and family to support; soldier lost no time only when absolutely obliged to do so: That about two years ago soldier had a shock of paralysis . . . he has been a wreck, unable to perform any manual labor and is at present partly demented unable to feed or dress himself, unfit to be left alone requiring the constant aid and attendance of his wife or another person, and his condition is gradually growing worse.5

Dr. J. K. Mason, one of Bemis's family physicians, from Suffield, Connecticut, observed that Bemis's

dizzy spells increased on him from year to year, & pointed unmistakably to this great injury of the brain. At length, in 1890 he had a severe Paralytic Shock—lying unconscious for several hours—from the effects of which he has never recovered not having done a day's work since. Though but 55 years old he walks like a man of 80!—not being able to dress himself nor tie up his shoe-strings. In all these little duties of every day life he requires constant attendance & assistance. . . . Also his memory, sight, & hearing are greatly impaired; & without my going further into details, you cannot but infer, & justly too, that he is but a wreck of his former self.6

In 1896, Mrs. E. D. Bemis sent a letter to the commissioner of pensions detailing her role as his primary care taker for nearly 30 years:

I am his attendant. My daughter is with me and assists some but if I were not able to care for him he would have to have a male attendant. . . . I have to assist him when he takes his bath as he cannot use the left hand but very little. . . . When his bowels trouble him his helplessness both in brain and body make my duties harder! We prepare his food at table as we would for a child, and when the lamps are lighted and we have fire it is not safe to have him long alone. There are times when he needs an attendant in the night. . . . I know his case is one that is hard to reach in the time given the veterans at the examining board for the most serious trouble is in the head.7

Less than a year later, a special examiner for the Pension Office visited Suffield, Hartford County, Connecticut, to verify Bemis's current medical condition. He interviewed Bemis, his wife, and other residents of the town. Jane Bemis described how she ran the household: I take charge of pension money, I dont trust him with any money, he signs the vouchers. . . . So far he has not been at all ugly so I have seen no use of having a conservator appointed over him of course it may come to that some day.8

By April 1900, Edson Bemis's mental state had declined so much that he could no longer remain at his home. Dr. Lewis L. Bryant and Dr. Walter E. Harvey examined Bemis and determined that he should be institutionalized. Dr. Bryant observed that Bemis believed

he was thirty years old: . . . did not know the present year month or day of the week: . . . has not been able to read since he was paralyzed: . . . cannot understand what he tries to read, and he cannot tell why: that the civil war is still going on: that once in a while he sees dogs in the room.9

On April 7 an order of commitment was completed to admit Bemis to the Westboro Insane Hospital in Worcester County, Massachusetts.10

At the end of the month, his sister, Celestia N. Bemis, took Bemis to her farm in North Brookfield, Worcester County, Massachusetts. Her deposition indicates that he was mostly bedridden. He had several falling spells and shocks that left him extremely weak. Celestia Bemis emphasized that Bemis's wife kept most of his pension payment and "took no interest at all in brothers care." Jennie Bemis's depositions, however, indicate that she had a strained relationship with her sister-in-law. Jennie Bemis offered to help with Bemis's care, "but my presence excited him so and Mrs. [Celestia] Bemis thought she could care for him better without me." The last time that Jennie Bemis saw her husband was toward the end of August 1900 because Celestia Bemis would not allow her in the house.11

In the final hours of his life, Bemis lost consciousness and then died on November 9, 1900. The death record shows the cause of death as "Cerebral Degeneration, the result of Gun Shot wounds during Civil War." He was buried in Suffield, Connecticut. Jennie Bemis continued to receive his pension until her death on January 20, 1917.12

Conclusion

The case study of Edson Bemis is one example of the many found in the MSHWR. The MSHWR may provide information that is not found in the records such as details about the soldier's medical condition and excerpts of letters sent to the editors. NARA records, including pensions and carded medical files, and National Museum of Health and Medicine records such as photographs, may provide additional details about the soldier and his medical history. If your ancestor survived an illness or injury, records can reveal ongoing health problems and their impact on the veteran and his immediate family.

Rebecca K. Sharp is an archives specialist in the Archives I Research Support Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. She specializes in federal records of genealogical interest.

Nancy Wing is a librarian and genealogy specialist in the Archives Library Information Center of the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Notes

1 U.S. Surgeon-General's Office, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865, Surgical Vol. II, pt. I, p. 162 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1870–1888).

2 Ibid.

3 Death record certification, Nov. 24, 1900; Certification of marriage record, Sept. 15, 1900; and Bureau of Pensions questionnaire, June 4, 1898; Edson D. Bemis Pension File (Widow's Certificate 528.308); Case Files of Approved Pension Applications (Civil War and Later Widows' Certificates); Civil War and Later Pension Files, 1861–1942; Records Relating to Pension and Bounty-Land Claims, 1773–1942; Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group (RG) 15; National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, DC.

4 Physician's affidavit, Dec. 31, 1885, Bemis pension, RG 15, NAB.

5 General affidavit, Jan. 22, 1892, ibid.

6 Letter to the Commissioner of Pensions, Dec. 13, 1895, ibid.

7 Letter to the Commissioner of Pensions, Dec. 30, 1896, ibid.

8 Jane A. Bemis's Deposition, Oct. 21, 1897, Bemis pension, ibid.

9 Medical Certificate, Apr. 7, 1900, ibid.

10 Order of Commitment, Apr. 7, 1900, ibid.

11 Depositions of Celestia N. Bemis, Nov. 25, 1901, and Jennie A. Bemis, July 2, 1901; Mr. Fairbanks, Special Examiner for the Pension Office, to the Commissioner of Pensions, July 2, 1901, ibid. Bemis's pension file notes that Celestia Bemis married an individual with the same last name. For additional information, see the September 10, 1900, deposition of Edson Austin Bemis.

12 Fairbanks to Commissioner of Pensions, July 2, 1901; Commonwealth of Massachusetts certification of death, Dec. 10, 1901; death record certification, Nov. 24, 1900; and May Bell Bemis to the Commissioner of Pensions, May 23, 1920, ibid.