What’s Cooking, Uncle Sam?

New Archives Exhibit Examines Government’s Effect on the American Diet

Summer 2011, Vol. 43, No. 2

By Alice Kamps

Frank N. Meyer was recruited by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for his passion for plants and his willingness to walk long distances. Determined to prove he was "the man for the job," Meyer traveled some 10,000 miles, mostly on foot, during expeditions to China, Siberia, and what was then Manchuria, Turkestan, and Mongolia.

The purpose of his travels, in his words, was to "skim the earth in search of good things for man."

The "good things" he sought were mainly new varieties of fruits, nuts, and grains for American agriculture. He trekked the far corners of the earth from 1905 to 1915, venturing into many territories that had never been explored. More than 2,500 types of seeds and shoots survived the journey home to be tested in American soils.

If the USDA were to develop a line of action figures, Meyer would top the list. Accessories sold separately would include his revolver—for frightening off bears, tigers, and wolves—and a Bowie knife for defending himself against murderous outlaws and bandits.

The USDA fastidiously documented the foreign plant explorations undertaken by Meyer and others. The photographs, correspondence, and maps tracing their journeys and discoveries line multiple shelves in the stacks of the National Archives.

Records illustrating Meyer's adventures are on display in "What's Cooking, Uncle Sam?"—an exhibition in the Lawrence F. O'Brien Gallery at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., through January 3, 2012. "What's Cooking?" comprises an eclectic assortment of records with one thing in common—they were produced in the course of U.S. government efforts to feed Americans an ample, safe, and nutritious diet.

Spanning the Revolutionary War era through the late 1900s, the documents, films, and photographs in the exhibition echo many of our current concerns about government's role in the health and safety of our food supply.

Wiley Campaigns Against Adulteration of Food

The exhibition explores government activities in four areas (Farm, Factory, Kitchen, and Table) that had an impact on food in America. Sometimes the impact was significant—the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 made it illegal to sell products doctored with toxic chemicals.

Sometimes the impact was less dramatic—Lyndon B. Johnson's Pedernales Chili recipe spiced up the cooking repertoire of some of his fans.Sometimes there was little or no impact at all, despite the government's best efforts—the World War II nutrition campaign had a negligible effect on eating habits. And sometimes the impact was completely unintended—many children of immigrant parents came to prefer the white bread they first tasted in their school lunches. The stories related here, like the others in the exhibition, provide context and insight into today's conversation about the role of government in our daily diet.

In the Factory section of the exhibition, we learn about an unusual experiment that took place in the basement of the Bureau of Chemistry. Just a few years before Meyer began traversing mountain passes and fording streams in Central Asia, Harvey Washington Wiley became the USDA's chief chemist.

Wiley had focused his career and his considerable skills, ambition, and energy on the subject of food adulterants. Tall, barrel-chested, with a monolithic head and penetrating gaze, Wiley was an imposing figure. He objected to food adulteration on moral grounds and approached his work with the zeal and passion of a crusader. Food adulteration was a fraud perpetrated on the American people, a fraud he was determined to expose to justice's harsh light.

Industrial age foodstuffs were commonly doctored with arsenic, formaldehyde, sodium benzoate, boric acid, copper sulfate, and other substances. These chemicals were added to foods as dyes or preservatives or to mask substandard ingredients and spoilage. Chemical preservatives, Wiley believed, posed the most danger to the consumer. But he needed proof.

Special Meals Prepared for 12 Brave Young Men

Wiley devised an experiment designed to provide evidence that these substances were indeed harmful. He rounded up 12 "young, robust fellows," to volunteer for what he called "the Hygienic Table."

Perhaps motivated by the promise of free meals, the medical students and Agriculture Department underlings signed on to eat food laced with progressively increasing amounts of chemical preservatives. Their motto: "None but the brave dare eat the fare."

The young men also committed to collect and submit all of their waste products for the duration of the experiment (a satchel and containers were provided for this purpose.) Wiley had a mail room kitted out as a dining hall complete with white tablecloths. "Old Borax," as Wiley came to be known, even prepared some of the meals himself.

The experiment surprised Wiley on two counts: the fascination it held for the press—who gleefully dubbed it "The Poison Squad"—and the severity of the illness caused by the adulterants. News of the Poison Squad contributed to the mounting public outcry for protection. The results of the tests (now in the Bureau of Chemistry Records of the National Archives) convinced Wiley that these substances should not be allowed in foods. In 1906 Wiley, and other supporters of the Pure Food and Drug Act, prevailed.

Our Eating Habits Become Matter of National Security

In the Kitchen section of "What's Cooking, Uncle Sam?" we learn how the government tried to protect Americans not only from unsafe food but from bad eating habits as well. In the years approaching America's engagement in World War II, nutrition became a matter of national security.

At the time, it was widely believed that a significant portion of Americans were malnourished. The health and fitness of the population were critical for both soldiers and civilians if America was to fight the war and maintain production of food and weapons on the home front.

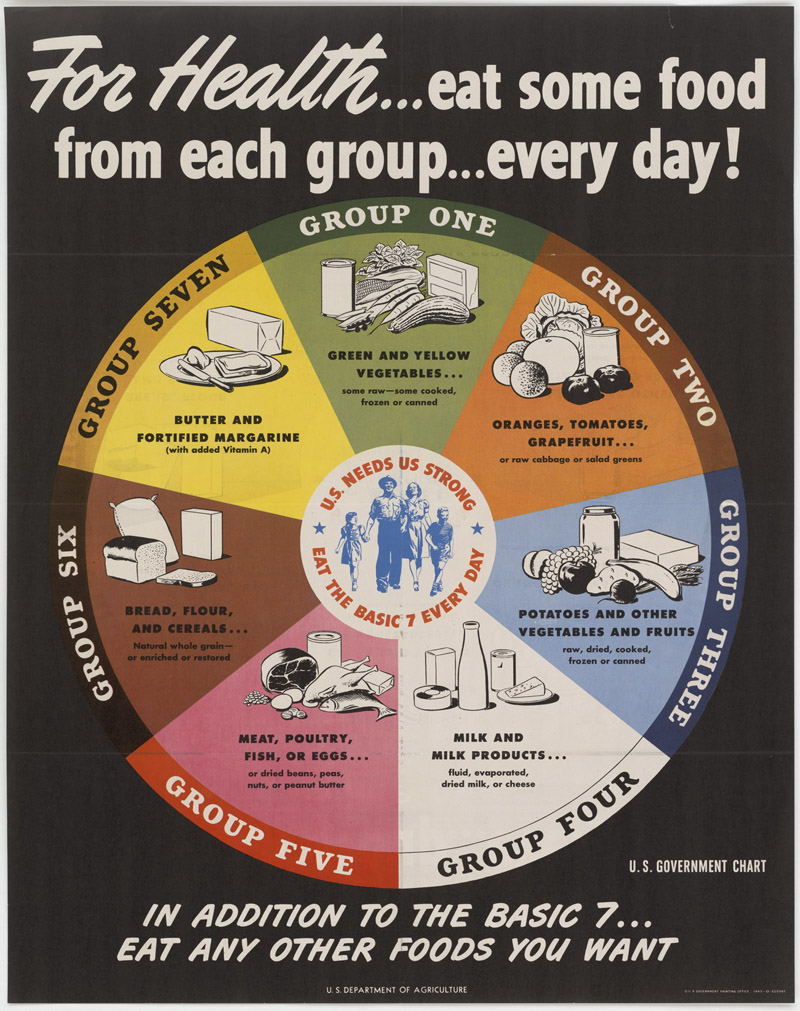

To combat this "hidden hunger," the Nutrition Division of the War Food Administration designed and deployed a new food guide to reflect the realities of wartime food shortages and rationing of meat, sugar, eggs, and butter. Previously in separate groups, meat and eggs were combined with beans and fish as alternative proteins.

The "Daily 7" was illustrated as segments of a circle. The freshly minted symbol of a healthy American family—designed with help from commercial advertising agency volunteers—was placed in the center. Around the symbol a spiffed-up slogan proclaimed, "U.S. Needs Us Strong—Eat the Basic 7 Every Day."

A version of that slogan, "U.S. Needs Us Strong—Eat Nutritional Food" was part of a separate initiative that co-opted the commercial food industry. The slogan and a special insignia modeled on the Good Housekeeping "seal of approval" could be used on foods approved by the Nutrition Division as part of a healthy diet. Requests for this endorsement poured into the Nutrition Division.

Eating breakfast cereal and other foods was quickly promoted as a patriotic contribution to the war effort. Even the Doughnut Corporation of America sought permission to promote their products as "Vitamin Doughnuts." After several months and pages of correspondence, the term "Enriched Flour Doughnuts" was officially sanctioned.

Assessing Uncle Sam's Impact on Our Diets

Teaching people about the nutritional value of foods was one thing; getting them to change their eating habits was quite another.

The National Research Council formed a Committee on Food Habits to explore ways to get Americans to apply the new rules to the packing of lunch pails and filling of grocery carts. Members of the committee were leading social scientists, including cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, who served as its full-time executive secretary. Although Mead was confident she could discover the links between culture and diet that would light the way forward, she seems only to have revealed how complex and difficult such an undertaking would be.

There are many more fascinating stories in "What's Cooking, Uncle Sam?" With more than 100 original records on display, there is much to discover about the scope and history of the government's effect on the American diet. The food records at the National Archives contain elements of tragedy, irony, gravity, and even mystery.

Our hero Frank N. Meyer is a good example of the latter. He embarked on his fourth and final expedition in 1916. Wearying of his travels and anxious about the deteriorating political situation in China, he had begun to consider resigning his post. Still, he kept on, collecting wild pears, peaches, and other plants.

On Friday, May 31, 1918, he boarded a riverboat on the Yangtze bound for Shanghai. That night, he was reported missing. Five days later, his body was found in the river. The circumstances of his death remain unknown.

"What's Cooking, Uncle Sam?" is on display in the Lawrence F. O'Brien Gallery at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., through January 3, 2012.

Alice Kamps became a curator at the National Archives in 2009. Before that, she was a freelance exhibit developer in Chicago, where she created exhibits for Shedd Aquarium and the Museum of Natural History. She started her museum career at Chicago Children's Museum. She has been a great fan of food since her earliest introduction and likes to think she "knows her onions."

Learn more about:

- This exhibition, "What's Cooking, Uncle Sam?"

- This exhibition's documents and images on Flickr.

- Other National Archives online exhibits.