Errors in the Constitution—Typographical and Congressional

Fall 2012, Vol. 44, No. 2

By Henry Bain

© 2012 by Henry Bain

Americans love their Constitution, even with its faults. And it has surely had some faults during its more than two centuries—some big faults that have been remedied, like slavery and Prohibition, and numerous smaller ones that are still with us, like the rule that has prevented the recent governors of California and Michigan from offering themselves as presidential candidates.

Americans love their Constitution, even with its faults. And it has surely had some faults during its more than two centuries—some big faults that have been remedied, like slavery and Prohibition, and numerous smaller ones that are still with us, like the rule that has prevented the recent governors of California and Michigan from offering themselves as presidential candidates.

A close study of the way the Constitution has been put on paper—either written or printed—during its long life is sure to call our attention to its smallest faults—its errors of penmanship and typography.

It is not surprising that a few such errors have crept in during all these years, while the original Constitution and an ever-growing body of amendments were written out on a few occasions and printed thousands of times. Most of the errors of the scribes and the typesetters were promptly corrected before we, the reading public, had a chance to notice them, but a few have endured in successive publications.

The earliest of the Constitution's errors were made by the scribe who produced the engrossed (written in a fine round hand) parchment and the printers who produced versions of the newly completed document in September 1787.

Production of the engrossed copy must have occupied much of the weekend remaining after the Convention's adjournment late on Saturday, September 15. The scribe was Jacob Shallus, assistant clerk of the Pennsylvania legislature. He did a fine job given the short time he had, spreading the more than 4,000 words across four large sheets of parchment.

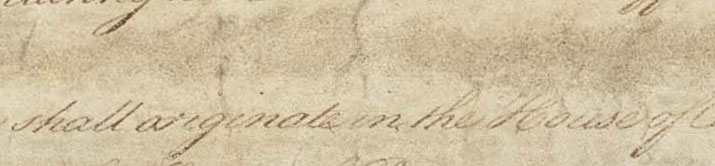

After he finished, Shallus had to deal with several mistakes that he had made during that rushed weekend of exacting labor. Many of the mistakes were omissions, and he tried to take care of each by inserting a word or two between the lines. But he also used a penknife to scrape away an entire line of text near the bottom of page one, leaving behind a roughed-up band that now appears gray from grime.

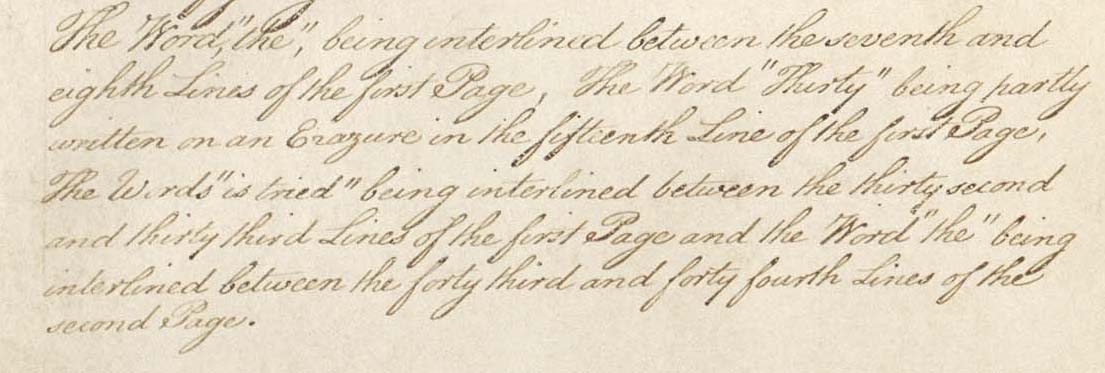

Another correction was the result not of a mistake, but of a last-minute change of mind by the Convention during the Monday session, when it increased the maximum allowable number of representatives from one per 40,000 persons to one per 30,000.

Also on page one are a number of ink splotches large and small, which occurred in the effort to complete this large document. Writing with a quill pen was a challenge.

On the last sheet, Shallus inscribed a record of the insertions so no one could think these might be illegitimate additions to the adopted text. After making his correction of the population per representative, Shallus explained it in his note of corrections: "The Word Thirty being partly written on an Erazure." Erasing ink isn't easy, and Shallus's effort to scrape away "forty" is easily detectable.

Alexander Hamilton Makes an Error

Providing evidence of the difficulty that we all face in getting things right, Shallus managed to make a mistake in one of his corrective notations. He wrote of "the Word 'the' being interlined between the forty third and forty fourth Lines of the second Page," but the insertion actually appears six lines farther down on the page, between lines 49 and 50. What's more, the scribe overlooked, and omitted from the note, another insertion of "the," just two lines farther down from the last error mentioned in the note.

Yet another error appears on the engrossed copy of the Constitution. It was committed not by Jacob Shallus but by Alexander Hamilton. As the members of the Convention prepared to sign the document, Hamilton took up a position beside the last of the four sheets, laid out for signing, and appears to have taken charge of the process as the delegates from each state came forward to sign. In this capacity, he wrote the name of each state at the left of the growing column of signatures. When he came to the largest state delegation, headed by Benjamin Franklin, he wrote "Pensylvania." And thus the parchment reads today.

While Shallus was spending much of the weekend inscribing those four sheets, the Philadelphia printers John Dunlap and David C. Claypoole were busy with an equally important task: producing 500 copies of the Constitution, some to be given to the Convention delegates as they departed, and some to be transmitted to the Congress of the Confederation.

The text produced by Dunlap and Claypoole contained a few more flaws. It must have contained the uncorrected "forty thousand"; it also cannot have had a correct list of the signers, for when the Convention began its final day, the members did not know precisely who was going to sign the document. There was a determined but unsuccessful effort, led by Benjamin Franklin, to bring aboard three delegates who had not committed themselves—Edmund Randolph, George Mason, and Elbridge Gerry. There was also some doubt, right up to the end, about another member—William Blount of North Carolina—who finally did sign.

We do not know how the print of Monday, September 17, dealt with these uncertainties. No copy of that print has ever come to light. (We do know that the printing was done, for the archives contain a record of payment to the printers large enough to cover two jobs, each running to 500 copies or more.) Apparently the stack of 500 prints was held closely by someone and not distributed. Otherwise, a few copies would likely have migrated into the papers of some members and could now be found preserved in various archives.

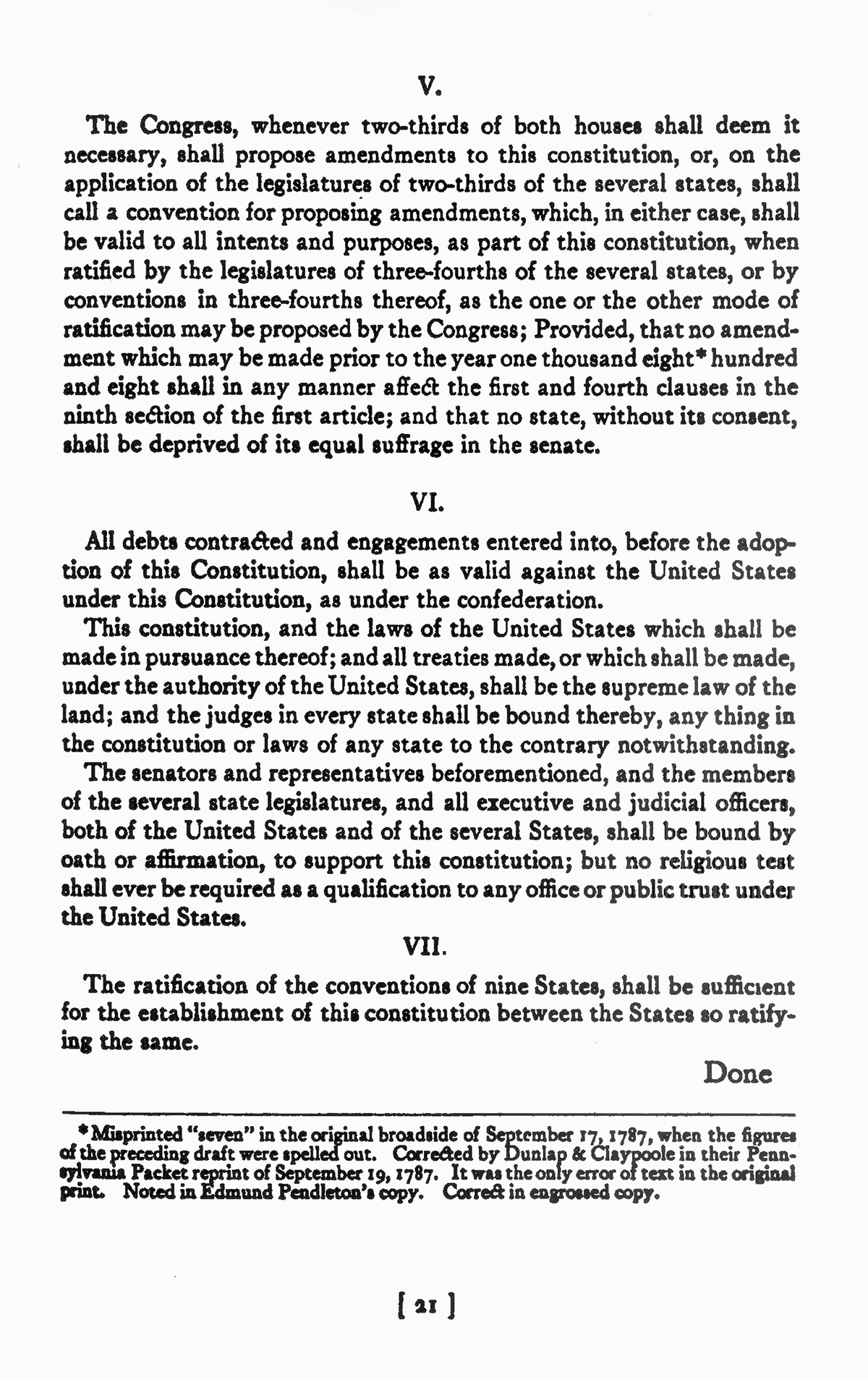

When Dunlap and Claypoole provided a fresh printing of the Constitution to the departing delegates on Tuesday morning, September 18, it contained a correct "thirty thousand" and an accurate list of the signers but introduced a new error. In Article V, in the clause that forbade, before the year 1808, any amendment affecting the slave trade, or the Article 1 ban on levying direct taxes without apportionment, the date was written as "one thousand seven hundred and eight."

We can perhaps charge this error to force of habit on the part of whichever member of the Convention's committee on style and arrangement was responsible for conveying the final decisions to the printers, or on the part of the printers. This error appeared in a few of the newspaper printings of the Constitution, both in Philadelphia and New York, during the next few days; these were soon replaced by correct copies and faded into history.

An Error-Free Version Appears

As the Republic moved into the new century, and the Constitution was reproduced by many printers, a new kind of error began to be noticeable. This was the presence, in many prints, of a scattering of small variations in punctuation, spelling, capitalization, and other stylistic details. The cause of any of these is impossible to ascertain, but they doubtless origi

nated partly as typesetting errors and partly as a result of the printers' idiosyncratic stylistic tastes.

This textual variability was enhanced by an unfortunate aspect of the printed Constitution's life history. For many decades after 1787, the national government failed to adopt and disseminate an official printing of the Constitution in booklet or broadside form. There was a copy of the Constitution at the front of the bound volumes containing the nation's laws, but these tomes were unlikely to be found in a print shop. In the absence of a recognizable official print, the nation's printers were obliged to copy whatever print might be at hand.

The result was the propagation and multiplication of a few irregularities in the early prints. Just a few days after Dunlap and Claypoole produced their print, John McLean of New York, the Confederation's printer, produced his own version, with a few small stylistic variations. A casual attitude to details of punctuation and orthography, which prevailed among printers and publishers in the nation's early years, allowed errors or irregularities to multiply.

William Hickey, a member of the Senate's clerical staff, noticed this situation in the 1840s as he prepared a text of the Constitution for printing. Hickey was struck by the inadequacies of the existing prints. "A printed copy (considered as correct) to print from, was found to contain several errors in the words, and sixty-five in the punctuation."

Hickey responded by publishing, in 1847, a copy of the Constitution from which he had taken pains to banish every error. He placed this Constitution at the front of a 225-page manual of the national government that he had produced, which in the course of several editions he expanded to 521 pages.

The book contained a certificate by Secretary of State James Buchanan, declaring that Hickey's printed Constitution "has been critically compared with the originals in this Department & found to be correct, in text, letter, & punctuation. It may, therefore, be relied upon as a standard edition." (Buchanan's original was the engrossed, signed original of 1787, in the custody of the Department of the State.)

Hickey published several editions of his manual, with the Constitution at the front, during the 1850s. After his death, the administrator of his estate published new editions in 1878 and 1879, with a certification by another secretary of state (Hamilton Fish) attesting to the accuracy of a Constitution that now included the three Civil War amendments.

With his careful work and the wide dissemination of his print, William Hickey struck a mighty blow for error-free reproduction of the Constitution. His work was carried forward during the late 19th century and afterward by the Government Printing Office. A modern pamphlet edition of the Constitution, printed by the GPO for a congressional committee, bears a close resemblance to Hickey's print.

Modern printings of the Constitution that follow the engrossed copy of the original can be identified by the many stylistic features in which Jacob Shallus's calligraphy departs from the style of the printers of 1787. The most conspicuous difference is Shallus's capitalization of almost all the nouns, in contrast to the very limited presence of capital letters in the work of the printers. The capital letters now help to give quotations from the Constitution, when taken from modern prints that follow the engrossed copy, an air of authenticity.

In the 17th Amendment, Not a Typo, But an Error

While the careful work of Hickey and the vigilance of the GPO have spared us the kind of random stylistic variation that plagued prints of the Constitution in the early 19th century, another kind of error put in an appearance in the 20th century. These errors might be called, not typographical, but congressional: mistakes committed, not by printers but by the members of Congress or their staff, who were responsible for shepherding the text of an amendment through the congressional process.

It might be argued that the language as proposed by Convention or Congress and duly ratified by the states is the authoritative text, and by definition error.free. While this may be true when the Constitution is being interpreted by the courts, a different standard is appropriate in a text to be used by citizens and students. By this standard, the Constitution contains two errors—textual elements that its authors did not intend and that are grammatically or substantively incorrect.

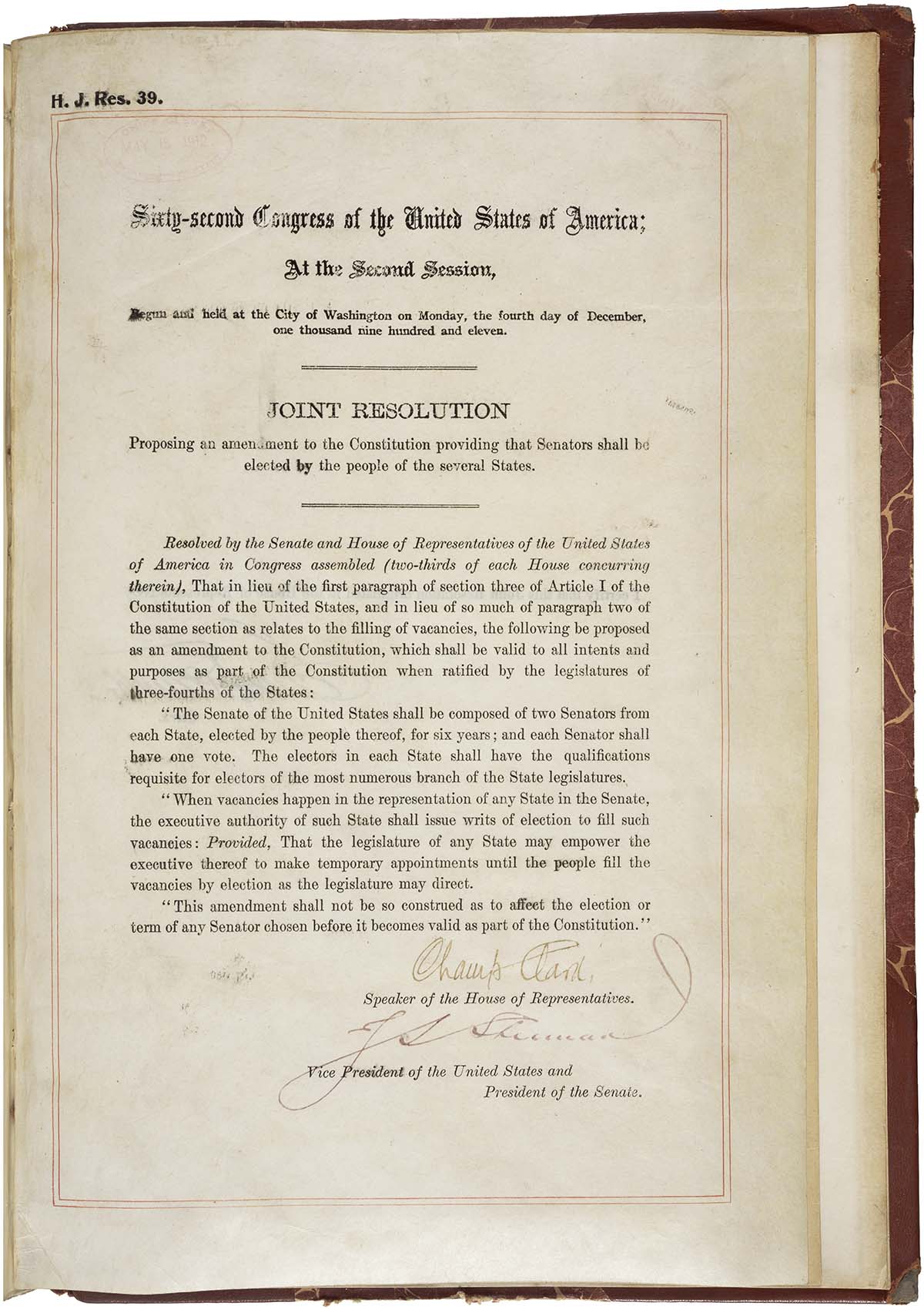

One of these errors is to be found in the 17th Amendment, section 1, which provides that "The electors [for U.S. senators] in each state shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the state legislatures." The final s is both contrary to the rules of English grammar (the singular "each state" should be matched by a singular "state legislature") and a departure from the corresponding text applying to the House of Representatives in Article I, section 2, clause 1, where "legislature" is singular.

A similar sentence, with small variations in wording and punctuation, appeared in many proposed amendments during the decades in which the popular election of senators was an issue. Some of these placed an s at the end of "legislature" while others did not, and some that were introduced with an s lost it as they moved through the congressional mill.

The language that eventually became the 17th Amendment first appeared, nearly in its final form, in an amendment prepared in 1892 by Representative Henry St. George Tucker of Virginia. The s appeared in Tucker's proposal, but it had disappeared by the time the joint resolution passed the House. No action by which the s was deleted (and another, more substantial change was made) is recorded in the Congressional Record.

In the next Congress, Tucker introduced an amendment that, he declared, was "in identically the same words" as the resolution the previous House had approved—but the s was back in place. It somehow again disappeared by the time the House approved the amendment.

Since the Senate of that era lacked a two-thirds majority in favor of such an amendment, both Tucker resolutions died. Similar proposals continued to be offered in succeeding Congresses, with continued typographical diversity.

The Surplus s Is Twice Removed

In early 1911, as public demand for direct election of senators grew ever stronger, a proposed amendment originating in the Senate nearly gained the necessary two-thirds of that body in a vote taken in the last days of the 61st Congress. This measure, a modification of a proposal introduced by Senator Joseph L. Bristow (a Progressive Republican from Kansas), contained the s.

Several senators voting against the amendment were about to lose their seats as a result of the 1910 election; some other opponents were retiring voluntarily. A dozen resolutions containing the long-agreed language were promptly introduced in the new Congress. In the House, five of them had the s while three did not; in the Senate, three had it and one did not. Recognizing that victory was at last within reach, the leadership of the new Democratic majority in the House of Representatives quickly brought a new joint resolution to a vote and sent it to the Senate.

The surplus s was present once again, and it was noticed during the debates in both chambers. One of those who noticed was Representative James R. Mann of Illinois, leader of the Republican minority. An opponent of direct election of senators, he reasserted his opposition in the debate on the amendment, but being heavily outvoted, he confined most of his effort to stylistic matters. As the House proceeded toward approval of the amendment, he remarked that "it has always seemed to me that the Constitution of the United States was sufficiently important to consider both the merits and the form of the amendments which might be adopted to it. . . . It has seemed to me that we might take sufficient time at least to put an amendment into proper grammatical and rhetorical shape." He offered several stylistic amendments to the text, including deletion of the final s in "legislatures."

All other changes were rejected as the amendment sped toward overwhelming approval, but the majority's floor manager told the House that "I would like to see the gentleman from Illinois gain one victory in this contest, and I therefore hope this amendment will be accepted. [Laughter.]" And it was.

Mann's "victory" came to naught, as Senate Republicans succeeded in substituting a different text for the House proposal in order to eliminate language, included at the insistence of the southern Democrats in the House, that would have exempted Senate elections from the regulatory power given to Congress. Senator Bristow had introduced the substitute language at the beginning of the session.

During the Senate debate, Bristow read aloud Article I, section 2, clause 1, on election of representatives and then the proposed substitute concerning election of senators. This juxtaposition apparently caused him to notice the difference between the language applying to the House (which uses the singular "legislature") and that in his proposed amendment (which referred to "legislatures"). He interjected, "I desire to say that, in line 2, page 2, of the proposed amendment, the word should be 'legislature' instead of 'legislatures'; that is, the s should be stricken off of the word, so that it will be singular instead of plural."

The Surplus s Proves Hard to Get Rid Of

Vice President James S. Sherman, in the chair, declared that "the amendment will be so modified, if there be no objection." No objection was noted, and the record of the subsequent proceedings shows no reversal of this action.

The next morning's New York Times bore evidence that Bristow might not have succeeded in deleting the s. In the full text of the amendment, printed on page 1, the s was still there.

Nine days later, when the House resumed its consideration of the amendment and began to debate the language just adopted by the Senate, the text that was read to the members was that of the Bristow amendment as introduced, with the s in place.

After some impassioned debate, the House voted to insist on its version of the amendment. A long impasse ensued—the conference committee of the two houses met 16 times over a span of nine months. Eventually, the House yielded and concurred in what it thought was the Senate version. But the joint resolution, as printed in the Statutes at Large and submitted to the states, contained the s.

Perhaps the most likely explanation for the hardiness of the surplus s is that the conference committee of the two houses mistakenly used the original print of the Bristow substitute as the raw materials for preparing its report to the House of Representatives, and this may then have served as copy for preparation of the print that was signed by the presiding officers of the two houses and sent to the states. Senator Bristow was not a member of the conference committee—perhaps this was a consequence of the Republicans' recent shift from majority to minority party.

Congress also removed a comma from the amendment, perhaps unintentionally. The Tucker proposals, as well as the House version of 1911, contain a comma after "election" near the end of the second paragraph of the amendment. The comma was not mentioned in the debates. It is absent from the 17th Amendment: "until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct."

No reference to the erroneous s has been found in contemporary or modern sources. It is not mentioned in any New York Times news report or in the reports by some other newspapers on the passage of the amendment in Congress. And no reference is made to the error in a lengthy doctoral dissertation on the amendment or in a biography of Senator Bristow.

The 25th Amendment: In Need of Another s

If the 17th Amendment has one s too many, the 25th has one too few. The first paragraph of section 4 provides that the Vice President, with "a majority . . . of the principal officers of the executive departments [plural]," may declare the President unable to perform his office, while the second paragraph provides that, if the President declares that no inability exists, the Vice President and "a majority . . . of the principal officers of the executive department [singular]" may reaffirm the President's inability, leaving the issue to a decision by Congress.

In all of the successive versions of the amendment that were considered by Congress on the way to the final language, "departments" was used consistently until one s disappeared in the final text produced by the conference committee of the two houses and adopted by the House on June 30 and by the Senate on July 6, 1965. The lack of an s was therefore an error—the result of hasty work in producing the conference report—rather than congressional intent.

The people on Capitol Hill were certainly trying to produce an error-free text. As the House of Representatives began its debate on the amendment, Emmanuel Celler of New York, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, requested unanimous consent to refer the report, already before the House, back to the conference committee "because of a technical error in copying." A moment later, after the House disposed of one other unanimous-consent item, Celler submitted the corrected conference report (apparently already prepared and signed by the conferees from both houses) and the final debate proceeded, with the lack of an s unnoticed by all.

Participants in the final congressional action on the amendment noticed the "department" error after both houses had approved the conference report and the joint resolution was ready to be signed by their presiding officers.

There was a brief discussion of the possibility of recalling the joint resolution for reconsideration in each chamber, but Congress was operating under severe time pressures as it worked toward adjournment for the summer, and it was decided that the record of congressional debates and actions on successive versions of the joint resolution made the intent so clear that the missing s could not affect interpretation of the text. The proposed amendment was therefore allowed to go to the states in its imperfect form.

The congressional staff members who had been working on the amendment did not know where the error had occurred but believed it more likely to have happened in the final typing of the conference report than in the typesetting at the Government Printing Office.

The two congressional errors in the Constitution present us with a remarkable symmetry. Each can be blamed on members of a conference committee or the assisting congressional staff, and each involved a wayward s, one incorrectly added to the text of an amendment and one incorrectly removed. The two errors can be expected to remain in all official copies of the Constitution for the foreseeable future—no modern Jacob Shallus or William Hickey seems likely to be able to correct them.

These two errors of Congress or its staff underscore the need for care in the often hectic and high-pressure business of producing Senate-House conference reports. The conference report is renowned as a wayward part of the legislative process, where all the refinements of members' thinking and negotiating can be cast aside as a very few members craft a final resolution of the many issues inherent in the typical legislative product.

Let us hope that any constitutional amendments that come through the congressional process in the future are given the calm and careful attention that is needed to prevent errors, congressional or otherwise.

Henry Bain is a political scientist who holds a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He has had a long career in governmental research and consulting and has taught at several universities. His modern edition of the Constitution will be published in 2013. His early research on voting gave the first statistically significant evidence that voters tend to favor the first candidate on the list. He also participated in the planning of the rapid transit systems in San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

Note on Sources

Information about Jacob Shallus was found in Arthur Plotnik, The Man Behind the Quill: Jacob Shallus, Calligrapher of the United States Constitution (Washington: National Archives and Records Administration, 1987).

Leonard Rapport wrote in detail about the various early editions of the Constitution in "Printing the Constitution: The Convention and Newspaper Imprints, August–November, 1787," Prologue: Journal of the National Archives 2 (Fall 1970): 69–89.

The print order of September 15, 1787, is given in the diary of delegate James McHenry.

The Dunlap and Claypoole print is reproduced in The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, House Document No. 96-143, 1979. For an explanation of the "1708" error, see p. 21. For detailed information on the printing process following the Convention's adjournment, see pp. 48–50. For the McLean print, see the Resolve Book of the Foreign Affairs Office, 1785–1789, National Archives Microfilm M247, roll 140.

The 1854 edition of William Hickey's manual is available from the Scholarly Publishing Office, University Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The modern pamphlet edition of the Constitution that closely follows Hickey's earlier print is The Constitution of the United States of America, as Amended. Unratified Amendments. Analytical Index, House Document 110-50, 2007.

The story of the 17th Amendment's journey through Congress is told in George H. Haynes, The Senate of the United States: Its History and Practice (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1938), pp. 106–117; Larry J. Easterling, "Sen. Joseph L. Bristow and the Seventeenth Amendment," Kansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Winter 1975): 488–511; A. Bower Sageser, Joseph L. Bristow: Kansas Progressive (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1968); and Wallace Worthy Hall, "The History and Effects of the Seventeenth Amendment," Ph.D. dissertation in political science, University of California, Berkeley (1936).

The disappearance and reappearance of the s is chronicled in these congressional files in the National Archives: Files of House and Senate Joint Resolutions, 52nd Congress, 53rd Congress, 56th Congress, and 62nd Congress.

Congressional debate is recorded in the Congressional Record, 52nd Cong., 2nd sess., January 16, 1893, Vol. 24, pt. 1, p. 617; 53rd Cong., 2nd sess., July 19, 1894, Vol. 26, pt. 8, p. 7724; 61st Cong., 3rd sess., February 28, 1911, Vol. 46, pt. 4, p. 3639; 62nd Cong., 1st sess., April 13, 1911, Vol. 47, pt. 1, p. 236, May 23, 1911, pt. 3, p. 1490 (in one printing of the Congressional Record, the page number is 1482), June 21, 1911, p. 2404; and 62nd Cong., 2nd sess., April 23, 1912, Vol. 48, pt. 5, p. 5169, May 13, 1912, Vol. 48, pt. 7, pp. 6367–6379.

John D. Feerick chronicled the 25th Amendment in The Twenty-fifth Amendment: Its Complete History and Earliest Applications (New York: Fordham University Press, 1976). Congressman Celler's conference report is in the Congressional Record, 89th Cong., 1st sess., June 30, 1965, vol. 111, pt. 11, p. 15212.

The decision to not recall the joint resolution for correction was confirmed with the late Larry A. Conrad, former chief counsel of the subcommittee on constitutional amendments, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, in a telephone interview.